Hippocrates in the Dark: A Doctor Experiences the Attack on Pearl Harbor

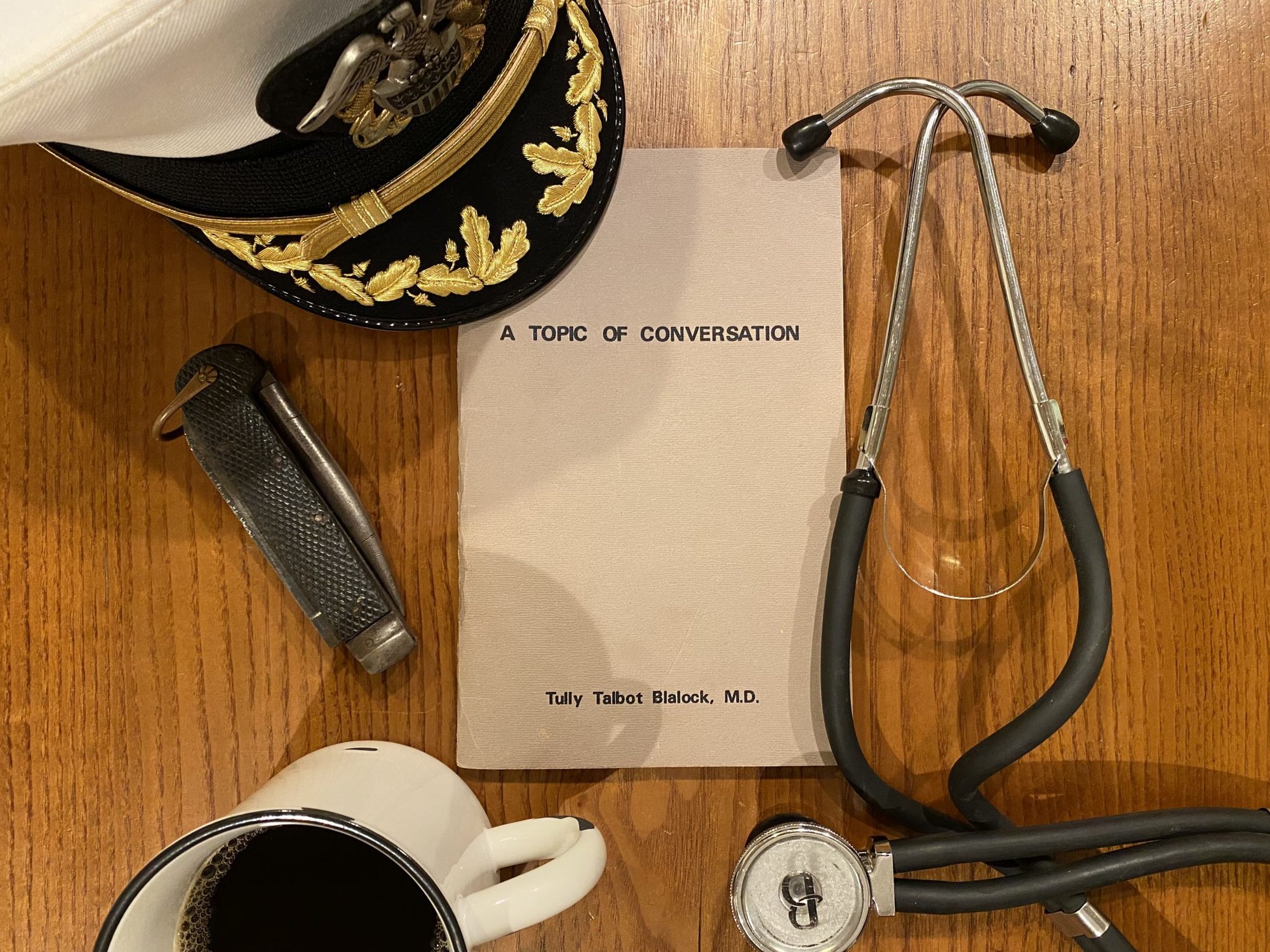

A Topic of Conversation, by Tully T. Blalock. Photo by Thomas Quinlen for Coffee or Die Magazine.

I knew my grandfather, Dr. Tully T. Blalock, as a warm, loving, active man, and while his personality was engaging by itself, there were a few other things that meant he was never going to go unnoticed. He was 6 feet 5 inches tall in a time before the NBA made such height seem commonplace. He was an identical twin, which meant there were two such giants wandering around. And he was a doctor of internal medicine in the age of midnight house calls. For many years after our grandfather had died, my cousin, his namesake, had people tell him stories of Dr. Blalock treating them or a family member — he made an impression wherever he went.

Like so many of their generation, my grandfather and his brother served in World War II, and when the war was over, they transitioned into civilian life. The children of the “greatest generation” might know some of what their parents did during the war, but who can guess how many extraordinary stories have been lost to future generations? Fortunately, my grandfather liked to write. And he wrote some stories about his and his brother’s time in the US Navy.

Two funny stories stand out. First, the doctor who did my grandfather’s physical examination was drunk and recorded his height as 6 feet. When my grandfather deployed aboard a minesweeper, a carpenter had to cut out the end of a berth so that my grandfather could hang his feet off the end of his bed. Second, my grandfather was assigned to conduct medical exams of two sailors arrested for jumping ship from the tank landing ship commanded by his twin. When Dr. Blalock walked into the room, the two men went white, believing their commanding officer had pursued them halfway around the world.

His most interesting story, though, was of his participation in the defense of Pearl Harbor.

The following was originally self-published in 1985 by Tully T. Blalock in a booklet passed on to family members.

‘A Topic of Conversation,’ by Tully T. Blalock

Each evening when I return home from the office after a day filled with emergencies, personal tragedies, and excitement, I sit down to relax, and Jean asks, “What happened today?”; I can never think of a single interesting thing that happened, and she turns to her household chores, convinced that I work in an isolation booth completely cut off from the rest of the world.

I have, therefore, been ever grateful to General Tojo and Admiral Yamamoto for affording me at least one day that has remained a surefire topic of conversation. WWII started behind the wheel of a vintage Packard coupe driving down Honolulu’s Kapiolani Boulevard shortly after 8 a.m. on Sunday, December 7, 1941. My war had actually begun a year earlier in 1940 when orders arrived to report to Mine Battle Force, Pacific Fleet, Pearl Harbor, for duty as Division Medical Officer, Mine Division One.

On this particular Sunday morning, a medical conference had been scheduled for 8:30 a.m. The sound of gunfire was unexpected for Sunday morning, although the Coast Artillery had been having gunnery practice on weekday mornings for some time. Suddenly, black mushrooms of smoke began to appear in the blue sky over the city, and all hell broke loose.

The road out to Pearl Harbor was a narrow two-lane strip leading westward over the marshy flats out to the Navy base. Within minutes, every soldier, sailor, and Marine on Oahu was trying to get his car or bus on that narrow road at the same time and at maximum speed. Periodically, the Japanese would strafe the highway, sending the automobiles spewing out at an angle on each side into the marshy ditch. If not mired down, they would all pull up on the road and head west at top speed. Entering the Pearl Harbor Navy base, it seemed as if the whole world was blowing up.

Smoke covered everything, and the noise was deafening. The naval hospital occupied a finger of land jutting out into the harbor pointing at the Ford Island air base just across the narrow channel. The main hospital building was surrounded on the shore side by a series of wooden temporary wards, each housing forty beds, two toilets, and a small examining room.

The commanding officer, Capt. Hayden, had stationed himself at the front entrance, and as each doctor arrived, he was assigned to a specific ward or service. The Packard was abandoned at Navy Landing “C.” Halfway to the main hospital building, a tremendous explosion rocked the entire area. Looking back, a towering pillar of smoke and fire covered the area, and debris rained down over the medical compound. This was the classic Life magazine picture of the Destroyer Shaw blowing up.

For the next hour, the attack continued. Japanese planes skimmed the hospital compound at treetop level, launching their torpedoes and bombs at the ships in the harbor and at Ford Island across the channel. Suddenly, one of the planes nosedived into the hospital tennis court, bounced up against the laboratory building, and disintegrated into a ball of fire. The only remnant of the pilot was a portion of the torso in a flight jacket. Much of the debris was collected by hospital personnel as souvenirs but was later confiscated by Navy Intelligence.

Each nurse was assigned to two wards, with one hospital corpsman per ward. Within two hours, there were 254 badly burned patients filling the beds, floor space, tables, and every conceivable space of wards “D” and “E.” As the first patient was brought in covered with oil grime and severely burned, he was put on the examining table. Before he could be given a shot of morphine, there were twenty more patients just like him on the floor outside.

Most of the men were in shock, all were in great pain, a few already dead, and more coming every minute. The personnel problem was solved by commandeering each stretcher-bearer, putting him to work cutting off the clothing and fetching supplies. There were no IV fluids, no plasma, no blood, no laboratory work. As the clothing was removed, it was evident that the burns were mainly on exposed areas — face, neck, arms, and legs. Even a thin T-shirt seemed to protect against the flash burns.

There were many deeper burns, shrapnel wounds, and crush injuries. Many of the men had inhaled smoke, water, and oil, and all were in acute respiratory distress. With all exposed areas burned, a major problem was finding an available vein for fluids when the supply arrived. With their clothing off, the men began to freeze, and the few blankets were soon exhausted. There was no heat in the building and no available heat cradles. Morphine was the only answer.

By 10 a.m., the attack was over, but the wounded poured in for another three or four hours, being brought in from the ships in the harbor and from Ford Island. By noon there were three doctors assigned to the two burn wards with one nurse, two corpsmen, and an assortment of machinists mates, bosuns, and seamen. They were all superb. The dedication, willingness, and gentleness of these untrained sailors were magnificent. They were real heroes.

Back at Waikiki, things were not going well either. As the neighbors congregated in each other’s apartments, rumors expanded until all the wives were convinced that the Japanese were storming the beaches and already overwhelming the island. Jean and her close friend, a destroyer captain’s wife, barricaded themselves in our second-floor apartment with a nickel-plated .38 for protection. Communications to the navy base were cut for three days, so neither group knew what had happened to the others.

Darkness brought new problems. No one knew if or when the Japanese might return. The island was in total blackout. Even the glow of a cigarette might bring a stray shot from a nervous Marine on guard duty. The waterfront in December was windy and cold. Blankets were still in short supply. All work had to be carried out with small blue flashlights, and even these brought warnings from the Marines manning the anti-aircraft batteries on the shoreline. Someone had the bright idea of painting the lightbulbs with blue paint and hanging them under blankets for warmth, but the bulbs could explode from the heat. There were no blackout curtains, and it was several days before the hospital painted the windows black.

During the night, there were two “air raids.” As it turned out, these were American planes coming in from the mainland. Fortunately, none were shot down. All supplies were soon depleted. For a while, there was not even morphine, but a new batch was finally obtained. Intravenous saline was made up in the hospital using distilled water and salt in clysis bottles with rubber tubing. Some dehydrated plasma was available but soon exhausted. Saline had to be given by subcutaneous route and nasogastric tubes because of the absence of available veins.

One sailor was given intraperitoneal fluids that dissected down the fascial planes and left him with a scrotum the size of a basketball. Burn treatment consisted of a washtub filled with mineral oil into which sulfanilamide powder had been stirred. Large gauze squares were then dipped into this mixture and laid over the burn. The mineral oil was soon exhausted, and the sulfanilamide powder was sprinkled on the surface of the burn.

Most of the patients were still covered with oil and grime, which was gradually removed as more help became available. Bowels and bladders were a major problem and were attended by our recruited assistants, who did yeomen’s work with very meager equipment. There were no antibiotics in 1941 — nothing but morphine and sulfanilamide. Many of the boys died that first night.

Excluding those who died from wounds and those who succumbed to pulmonary complications of inhaling oil, smoke, and seawater, the corrected mortality rate was published at 15%. This seems an incredible figure, in view of the primitive treatment. Many of the boys sent back to the mainland died later of complications, so the figure may have to be revised.

It was a day never to be forgotten.

Read Next:Pearl Harbor Sailors Who Perished in Attack Identified After 79 Years

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.