To Hell and Back Again: The Epic Adventures of British Commando Freddy Spencer Chapman

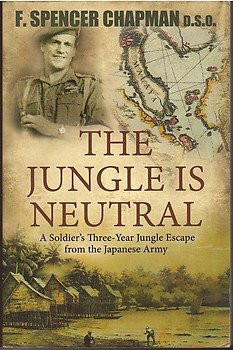

Three years and five months spent in the Malayan jungle battling typhus, pneumonia, blackwater fever, cerebral malaria — two weeks of which was spent in a coma — represent half of the battles British commando Freddy Spencer Chapman faced during his unbelievable fight against the Japanese in Malaya during World War II.

The British war hero was far more than an experienced survivalist — he loved nature and documented it in journals as a botanist; led an advanced polar exploration in the frozen tundra of Greenland with sled dogs; journeyed as an alpinist in the Himalayas; and led run-and-gun operations in Southeast Asia, escaping using instinct from captivity and capture. Chapman even once disguised himself as a Chinese laborer and slipped out to sea to be rescued by a Royal Navy submarine.

Chapman’s relentless pursuit to push the boundaries of competition through physical challenges, mental fortitude, and education continues to inspire future generations to achieve the impossible.

Greenland, Eskimos, and Polar Bears

Chapman expressed an interest in polar exploration when fellow Cambridge classmate Gino Watkins traversed Labrador, a previously unmapped territory in northeast Canada that borders Newfoundland, in 1928 and 1929. Chapman, enthralled by Watkins’ success, broke the ice of his first mini polar expedition to Iceland during his summer vacation the same year to study bird species and plant life.

But according to Linda Parker’s book “Ice Steel and Fire: British Explorers in Peace and War 1921-1945,” Chapman confessed in his 1951 book “Helvellyn to Himalaya” that he “wanted to experience again the thrill of setting out on some difficult or dangerous enterprise with friends of similar tastes.”

The difficult living conditions and glow of challenge motivated him to ditch a career in academia to join Watkins in Greenland as protege. The highly experienced team added three members from the Royal Air Force Reserve to act as a photographer, a scientist, and a team doctor, in addition to their piloting duties. In total, there were 14 men on the team.

The British Arctic Air Route Expedition mission of 1930 to 1931 was executed precisely to survey the possibility of an air route between North America and Europe by way of the Arctic. In addition, it improved upon the previous inaccurate maps of the region. Traveling aboard the Quest, Ernest Shackleton’s famed ship, the crew linked up with J.M. Scott accompanied by 49 husky sled dogs (seven teams of seven) and a band of Eskimos in small, seal-skin sewn kayaks to set up a temporary camp. The following day, the team set off for Base Fjord, an impeccable location where the Quest could anchor and seaplanes could land.

It had a path between a glacier leading to the Ice Cap Station that they used for their journeys. At times, with great physical agony, one member could transport up to 120 pounds of supplies to upstand their new staging area. No detail in each following mission was overlooked — the desolate miles of ice and unforgiving 100 mph winds didn’t discriminate amongst the men who were conducting aerial reconnaissance and establishing meteorological stations. Chapman was responsible for hunting seals using techniques taught by the Eskimos and fending off territorial polar bears.

[vimeo id=”100516379″ /]

He recalled one engagement when focusing his camera: “Suddenly up and saw (sic) that in an amazingly short space of time the bear with great agility had clambered out onto an ice floe and had turned, snarling, to attack. I dropped my camera into the bottom of the boat and seizing the rifle … took a snap shot at the bear just as he was about to leap into the boat. We were so near that as he fell forward stone-dead he almost upset the boat with the splash of his huge body.”

Over 13 months and seven journeys, the crew overcame extraordinary perils. August Courtauld went as far as to volunteer to live alone in the Ice Cap Station from December to May to keep their progress alive from desertion. Courtauld wrote the introduction in Chapman’s book “Watkins’ Last Expedition,” which read, “The memory will never fade of that little tent we shared, the thoughts we shared, the fear we shared, on such a journey you get to know the worth of a man.”

On May 5, the team reunited to find Courtauld’s hut almost completely covered with snow despite an exposed ventilation vent protruding 2 feet into the air; he was still alive. They learned how to combine surveying techniques from the land, sea, and air to give the best compact picture.

“The memory will never fade of that little tent we shared, the thoughts we shared, the fear we shared, on such a journey you get to know the worth of a man.”

Living amongst the Eskimos and learning the Inuit language, Chapman developed a perspective that would act as the foundation to his years spent in war: “Almost all difficulties can be overcome. Mere cold is a friend, not an enemy; the weather always gets better if you wait long enough; distance is merely relative; man can exist for a very long time on very little food; the human body is capable of bearing immense privation; miracles still happen; it is the state of mind that is important.”

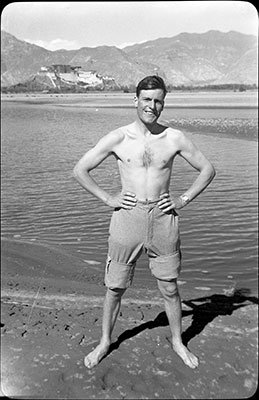

Upon Chapman’s return from Greenland and a brief teaching stint in the spring of 1936, his thirst for adventure took him to “The Divine Queen of Mountains,” or Chimolhari, the unexplored range between Bhutan and Tibet. He conquered it in five days, despite almost falling from a 3,000-foot ice face — he saved himself using an ice axe. The feat was another mark on his climbing resume, one that no one else achieved for another 33 years.

His mountaineering and climbing fix was halted while training for an aborted expedition to Finland, so he began teaching survival skills in Lochailort, Scotland, in what became the Special Training School 101 (STS 101). The advanced training designed under the Special Operations Executive was later molded into its Far East detachment, commonly referred to as Force 136.

Raising “Stay Behind” Parties

Chapman taught fieldcraft to set up a commando unit in New Zealand in August 1941 before commanding a small guerilla warfare school in Singapore. He and “Mad” Mike Calvert — who later raised hell conducting long-range penetration missions as a column commander under the infamous Wingate’s Chindits — worked together in Singapore and were responsible for standing up a commando force in Australia.

Military leaders and strategists, however, wouldn’t allow for preparations to be made in the event that Singapore fell — they didn’t believe it could happen. Then, on Dec. 8, 1941, the Japanese lit up the Singapore sky with aerial bombardments. With the reactionary mindset in Malaya, Chapman’s previously planned force comprised of planters and tin-miners from sympathetic guerillas from the Volunteers (Malays, Chinese, Indians) — who carried the essentials in language and geographical capabilities — were scraped together at the last minute.

Come January, this force would act as “left-behind” parties, though Chapman preferred the term “stay behind” because it felt less abandoned. If caught, torture was guaranteed and execution likely. Many of his comrades’ headless corpses were later discovered.

Singapore became a strategic win, and Japanese Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka believed it could leverage momentum in taking over England.

The communications system amongst the 50 British officers under his command who were located around the country wasn’t optimal — they had one transmission set at the headquarters north of Tanjong Malim. If things got hairy enough, and they often did, he had to send a signal to Singapore so it could be transmitted as an after-news announcement. With limited equipment, outdated maps, and mountainous terrain that could only be climbed by avoiding the moss-covered boulders and using buried roots as handles — the enemy wasn’t the only obstacle.

When Singapore fell, General Tomoyuki Yamashita conquered Malaya in just 70 days, which earned him the epithet “Tiger of Malaya.” Churchill initially expected that more than 100,000 British, Canadian, Australian, Indian, and Malayan troops could repel the Japanese, as evidenced by his telegrams sent between him and ABDACOM (American-British-Dutch-Australian Command). “The Gibraltar of the East” wasn’t the military fortress they expected it to be.

Singapore became a strategic win, and Japanese Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka believed it could leverage momentum in taking over England. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the Special Operations Executive in the Far East had other plans.

Jungle Warrior

The jungle erases all confidence one brings with their arsenal, tested through years of survival training in the harshest landscapes. The desert’s unrelenting heat and the arctic’s raw temperatures barely compared to the hidden terror the jungle held. The vegetation of vines and thorns bushwhacked in half by long jungle knives often shook loose and disturbed venomous reptiles, poisonous spiders, and nests of insects whose sting was like a bullet.

The knee-deep swamps, fallen trees, and jagged rocks blocked paths leading to more strenuous walking routes. The torrential downpours soaked their clothing, disintegrated the matches they used for warmth, and quelled visibility. When the rain let up, the humidity suffocated their taxed lungs. For Chapman’s party, simply existing was difficult, never mind the threat of the Japanese that hunted their every move, at times using Alsatian police dogs to track them.

At night, when forced to sleep, they perched above the ground in leaf beds to avoid the creeping Trap Jaw ants and the spitting cobra, shivering in their wet clothes. Mosquitos and sand flies attacked their faces; upon waking, cold water helped pry open their swollen eyes. Although their clothes protected most of their body, leeches always found a way into the most sensitive areas. When the sun rose, the symphony of deafening jungle life quieted.

“Three of us managed to wreck seven trains, to cut the railway in about sixty places including demolishing 15 bridges, and to damage or destroy forty motor vehicles.”

Once Chapman convinced the Chinese to approve attacking Japanese supply lines headed for Singapore, the real work began the following fortnight. Whilst operating beyond five miles of the Chinese valley that protected his three-man party, they used a map to mark footpaths and cut-throughs to easily infiltrate and sabotage the railway using pressure switches to initiate the explosives. Secondary devices, though smaller and on delayed-action fuses, were placed near the main targets to discourage the Japanese from fixing the tracks.

As they returned from nighttime missions, the daylight exposed them to the Japanese. The enemy unknowingly passed by the British commandos who discreetly impersonated Indians by using a mixture of coffee, potassium pomegranate, lampblack, and iodine to dye their skin.

Once the Japanese began hardening the railroad with security, they stalked roadways until unleashing gelignite improvised explosive devices (IEDs) — typically used for blasting large boulders — upon the vehicles before opening up with their Tommy Guns. They moved light with loads that didn’t exceed 25 pounds and struck with ferocity. Chapman estimated each of these operations lasted approximately 20 seconds before disappearing into the jungle that protected them from retaliation.

He later wrote, “Three of us managed to wreck seven trains, to cut the railway in about sixty places including demolishing 15 bridges, and to damage or destroy forty motor vehicles; we also killed or wounded between five and fifteen hundred Japs [sic].” He estimated “..that the Japs [sic], being under the impression that there were two hundred Australians operating in the jungle, had stopped two thousand frontline troops at Tanjong Malim especially to hunt us down.”

Isolated and Sick — but Productive

On May 1, 1942, while under curfew, Chapman took a 50-mile bike ride toward a communications set that could confirm or deny speculated rumors. During the ride, a Malayan policeman stopped him. As Chapman broke away, the policeman fired, wounding him in the left calf. Chapman escaped, and on July 13, he linked up with the Pahang Guerillas, the least-trained “soldiers” formed under the Malayan Communist Party after the fall of Singapore. For a year, Chapman saw no other white men. He spent that time healing from the sickness that halted his ability to move ably around; he also hunted deer, pigs, and monkeys to provide nourishment to their poor living conditions.

In addition to his hunting and gathering, Chapman taught military instruction to eager guerillas despite his impressions of their intuition. “It was with the utmost difficulty that we could teach some of the recruits to march in step, and many of them were constitutionally incapable of closing one eye in order to sight a rifle,” he recalled. “Nor have I ever met men with so little regard for the normal principles of safety.”

Chapman’s communication with the outside world was minimal; much of what he learned about the status of Europe, Burma, and Australia was through falsified Japanese propaganda.

“As long as I was well, my chief trouble was lack of reading material,” he wrote. “I also suffered from acute sense of frustration. In the first place, on any previous expedition I had always made collections for the British Museum of Kew; but here, as I had no previous knowledge of Malayan flora or fauna, I had no idea whether an insect or a bird that I saw was one of the most commonest species or new to science.” Chapman stated that though he kept several full journals of insects, plants, and jungle birds, many fell into the hands of the Japanese.

Chapman’s communication with the outside world was minimal; much of what he learned about the status of Europe, Burma, and Australia was through falsified Japanese propaganda. However, in order to escape, he knew he had to journey to other bandit camps and meet other British officers. Some trips took hours, others took weeks. Progress was slow over the next several months.

Capture and Escape

On Christmas Day 1943, Chapman connected with Colonel J.L.H. Davis (who later earned Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire/Distinguished Service Medal, or CBE/DSO) of the Malayan police and Colonel R.N. Broome (who later earned the Military Cross) of the Malayan Civil Service. Both fluent in Chinese and members of Force 136, the leaders became successful in receiving submarine sorties of wireless sets unfortunately too waterlogged to survive. For the next 18 months of radio silence, Chapman joined a group of Chinese marauders who were greedier and less friendly than the other guerillas. They confiscated his weapons and held him as a prisoner.

The night of May 10, 1944, Chapman doped his guards using a lethal dose of morphia in their cups of coffee, slipped through a shortcut along the Chemor River, and met two Sakai washing themselves on the bank. It became clear that it was a Japanese camp, and he was immediately surrounded by hundreds of soldiers demanding to know where he had come from. They seized his diary, as had been done many times before, except it couldn’t be translated because everything was written in Eskimo.

This time he coerced the Japanese by lying about his disillusionment of the Chinese, so they let him sleep without restraints. He managed to escape when the sentries turned away that evening. For the next six days he raced barefoot to confuse trackers, ulcers nagging his feet, hiding out in empty Sakai huts that sheltered him while he recovered from his many ongoing illnesses. A Japanese patrol targeted one of his huts and set it on fire — but not before he was out the back in “bolt hole.”

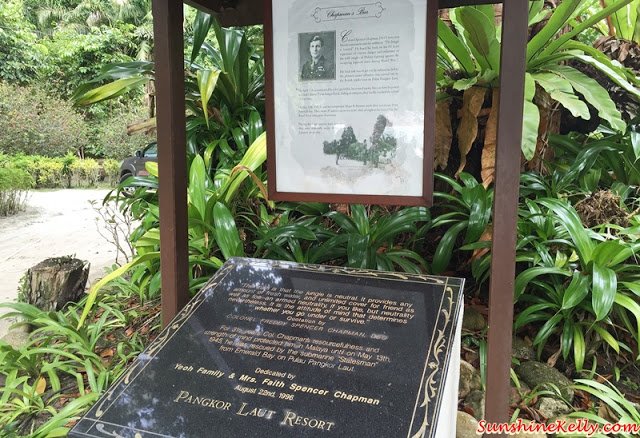

Determined to fight against lingering sickness and a splitting headache, Chapman recovered in a village for several months while Davis and Broome began establishing improved wireless sets. Prior to their entry by submarine, aircraft hadn’t roamed the skies, so their emphasis was to enact a regular schedule to drop supplies between Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and India. Come April 1945, Chapman and Broome arranged to rendezvous with a submarine off the west coast of Emerald Bay, Pulau Pangkor Laut.

Chapman’s Challenge

For 15 days, Chapman and a few guerillas disguised as Chinese laborers hid in Sampans and avoided roving Japanese patrols. On the night of May 13, 1945, a large dark sail raised from the bay and a submariner from the HMS Statesman shouted in code: “Ahoy! How are your feet?” Chapman eagerly responded, “We are thirsty!” He then swam 45 meters out to sea before escaping back to Ceylon. He was “missing, believed killed,” and by the time of the surrender, Force 136 had trained 3,500 armed guerillas. Determined to return to Malaya, Chapman reasoned that jumping from an airplane is an experience so unpleasant that a course is not necessary. He made the jump and rekindled a relationship with liaison officers before the war’s end.

Paying homage to that daring escape, from May 10 to May 12, 2019, in the fourth annual run honoring Chapman’s legacy, ironman enthusiasts will race the jungle from which Chapman was rescued. The Chapman’s Challenge entails a 3.8-kilometer (2.36 mile) road run, a 2.4-kilometer (1.49 mile) jungle trail, a 1-kilometer (.62 mile or 1,000 meter) swim in Emerald Bay, and a 30-meter sprint to the finish at Chapman’s Bar.

Coffee or Die reached out to Hazel Spencer Chapman, granddaughter of Freddy Spencer Chapman and a creative art director, who competes annually in the race.

“The Chapman’s Challenge was started by Pangkor Laut resort in memory of Freddy, and they always kept the beach where he was rescued undeveloped to maintain how it would have been,” she said.

While competing in the race, Hazel thought of Freddy to overcome her hardships, “We did the race on the anniversary of the day he was rescued — and swimming out, that was in my mind, imagining how it would have felt for him. When I felt any physical struggle during the race, I not only thought of the attitude of mind over body but the insignificance of what a 1-hour race was in comparison to 3.5 years.”

Alongside her brother, Stephen Spencer-Chapman, a captain in the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment in the British Army, the pair finished in fourth and fifth places in 2016. Stephen has gone on to place as high as third in subsequent years.

Racers, under less stressful circumstances, gather some insight into Chapman’s experience in the jungle; however, it’s a lesson that many jungle warriors across the globe have reconciled. Chapman spoke to this during a lecture to the Alpine Club on Dec. 8, 1947.

“There is one school of thought — that of the six British soldiers of whom I already spoken — who see the jungle full of innumerable visible and invisible horrors — scorpions, snakes, and centipedes, deadly fevers, ferocious wild animals, and hostile natives. Then there is another, who think that the jungle is teeming with game, fish, and edible roots, and fungi, and that bunches of bananas and pineapples drop into one’s lap. Both these viewpoints are equally false; but the jungle does provide unlimited fresh water and cover where Englishman as well as Japs [sic] may hide. It is the attitude of mind that is all important: the jungle itself is neutral — though admittedly it is an armed neutrality.”

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.