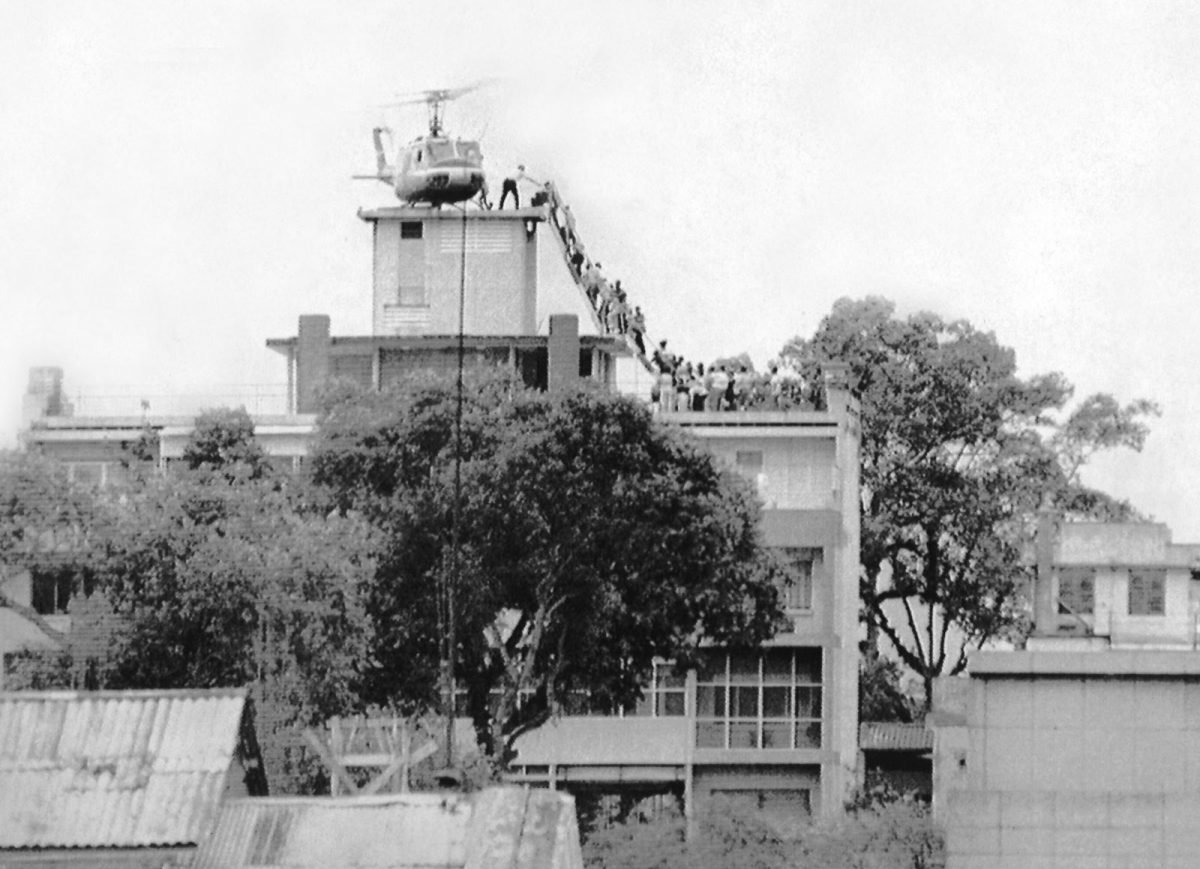

Air America pilots land on the roof of a CIA safe house where the South Vietnamese prime minister and his family awaited evacuation. Refugees on the roof made a makeshift ladder for a last chance of escape from Saigon. Photo by Hubert Van Es, April 29, 1975.

Bob Lemke remembers the morning he realized Vietnam was lost. “The radar looked a little fuzzy only because there was so much activity on the water,” Lemke, then a lieutenant on the frigate USS Kirk, told Jan K. Herman in The Lucky Few. Gathered around the ship, Lt. Lemke saw “every type of watercraft from small fishing vessels to rubber rafts.”

The radar was being washed out by some of the thousands of Vietnamese refugees who had taken to boats, rafts, and anything that could float in a desperate attempt to reach American ships, such as the Kirk, waiting offshore.

Sitting 12 miles out to sea from Vung Tau Harbor, the lieutenant was shocked to see a tiny wooden dugout canoe with a man, woman, and two children clinging onto it for dear life. “These people were simply paddling out to sea hoping to get to the rescue ships,” he wrote.

In late April 1975, North Vietnamese forces pushed into Saigon, rolling over South Vietnamese resistance and pushing American forces out of Vietnam for good. The evacuation that followed was, for many, the sign that the bitter conflict was finally drawing to a close.

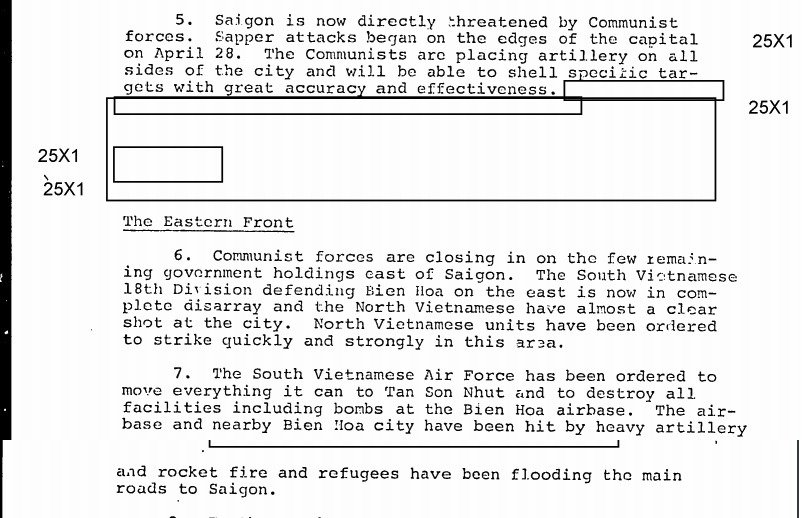

The situation on land was dire. A declassified CIA situation report, written April 28, detailed the grave state of the fighting: “Some Marines are still reported holding on at the Long Binh logistics complex, but they are surrounded and do not stand much of a chance to hold out for long.”

Militarily, Operation Frequent Wind (no, really) was a success in most aspects. Yet, those who participated would tell you that they wished they could have done more.

Bob Caron, a pilot for the CIA’s covert fleet of transport planes nicknamed “Air America,” told Northwest Florida Daily News in 2015 that “we got as many people as we could. But as word spread and people saw the helicopter taking off and landing, more and more people showed up. Looking back, that’s the hardest thing for me — knowing that we couldn’t save everyone.”

On the offshore ships, such as the Kirk, a bigger problem was quickly developing: South Vietnamese aircraft were bringing a constant flow of refugees to ships. However, once the helicopters landed, the pilots often refused to take off again. Many helicopters were pushed off the ships into the ocean to keep decks clear.

Operation Frequent Wind is still considered the largest evacuation ever conducted by the US military. In the last week of April 1975, approximately 70,000 South Vietnamese were evacuated, most by boat. In one day, 81 helicopters carried more than 1,000 Americans and almost 6,000 Vietnamese to waiting US ships. Navy ships off the coast of Vung Tau picked up as many refugees from the water as they could.

Many refugees who reached US ships remember the sailors who took them in fondly. In the midst of the terrifying experience of fleeing their homes and a brutal war, most of the refugees were met with compassion and understanding by the crews, who knew that the families were risking their lives to avoid living under a communist regime, the refugees reported.

A similar situation may be brewing in Afghanistan, where interpreters and other contractors who have worked with US forces fear a Taliban takeover after America’s looming exit. The Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs at Brown University released a report this year noting that, in 2019, there were 18,800 backlogged applications for Special Immigrant Visas for Afghan and Iraqi contractors.

“The program has been plagued by bureaucratic inefficiencies and significant problems with the application process,” Noah Coburn, the study’s author, wrote. “The lives of thousands of these applicants are currently at risk.”

Read Next: How a Navy Seabee Was Awarded the Medal of Honor Alongside a Green Beret

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.