For Mob and Country: 4 Gangsters Who Served or Assisted the US Military

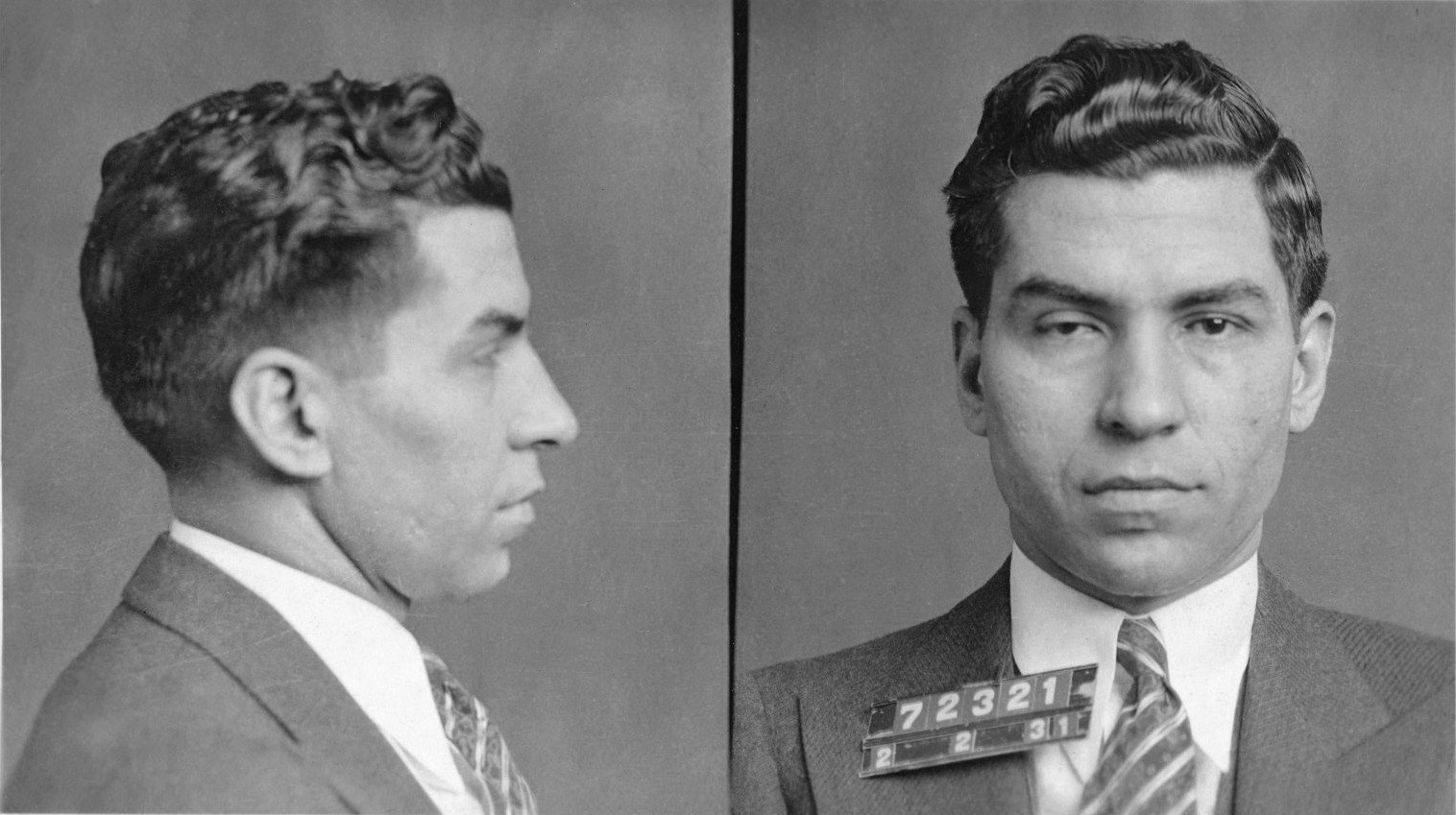

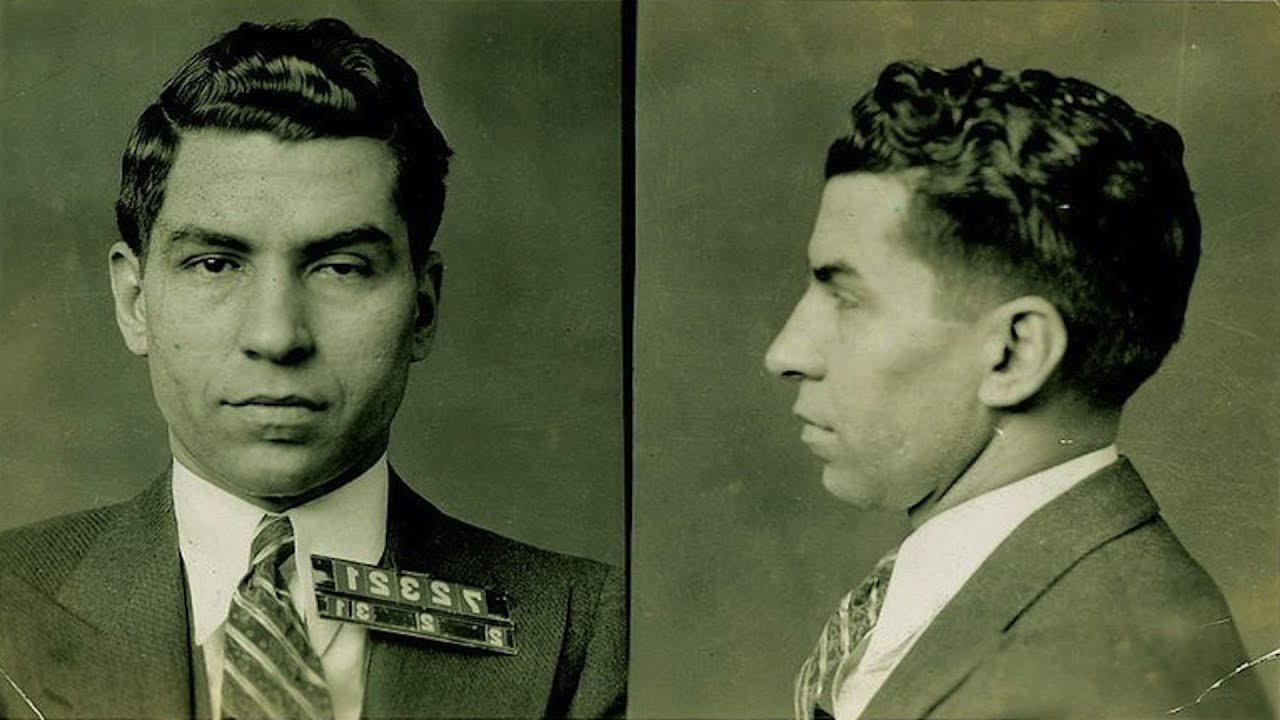

1931 New York Police Department mugshot of Lucky Luciano. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The US military is composed of people from all walks of life, and hardcore gangsters are no exception.

We’ve rounded up four mobsters with wild stories who served or assisted the US military — a tattooed bare-knuckled bruiser in the trenches of World War I, a savvy logistics officer who provided deployed troops better hygiene, a hitman who participated in the Iwo Jima invasion, and an Italian ruffian who helped catch German spies on the home front in return for a prison pardon.

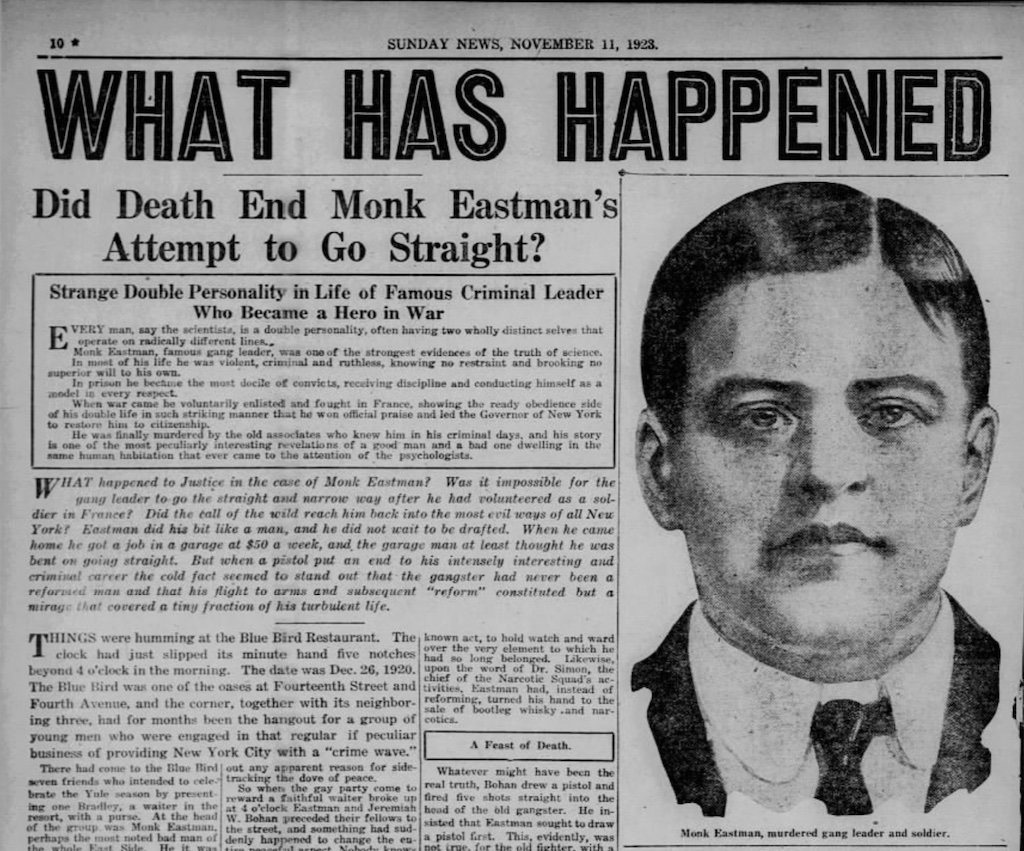

Monk Eastman

Edward “Monk” Eastman was a New York City mob boss for the Lower East Side’s Jewish-American Eastman Gang. Beginning in the 1890s and through their heyday at the turn of the 20th century, Eastman acquired an army of 1,200 gangsters. Politicians and the police were in his pockets while his gang ran brothels, protection rackets, and drug rings without worry of being shut down. The violence in the city, however, became too frequent, and the corrupt figures he previously had control over turned against him. He was arrested in 1904 and sentenced to 10 years in Sing Sing prison. When he was released, he had lost everything — control of his territory and his identity.

The former 44-year-old street kingpin and enforcer instead joined the New York National Guard in 1917. The young doughboys in the 106th Infantry, 27th Division — better known as O’Ryan’s Roughnecks — teased the old brawler at a trench warfare school in South Carolina as they prepared for war-torn Europe. When his secret was revealed, he earned instant respect, only to add to his legend for his service record overseas. The Roughnecks were sent to Poperinghe Line in the Ypres Salient. Eastman engaged in hand-to-hand combat, hurling his tattooed knuckles and breaking the faces of German assaulters.

A bullet struck him in the hand during a firefight, and although he was wounded, he wrapped his hand in a bandage and rescued a fallen teammate. He used hand grenades to suppress a machine-gun emplacement. He was even wounded by shrapnel in his leg, and when his unit prepared to take on the impregnable Hindenburg Line, he escaped from the hospital to rejoin his fellow soldiers. Toward the end of the war he served as a stretcher bearer, shuffling the wounded from the trenches to safety. When he returned home to a hero’s welcome, the celebration for a reformed mobster was cut short. He was shot dead in December 1920 and was buried with full military honors.

Moe Dalitz

Not all gangsters were enforcers. Morris “Moe” Dalitz had the financial wealth and political influence needed to transform a city like Las Vegas into a nightlife wonderland. He was short in stature and had a soft-spoken voice. In the limelight he had a gentle presence about him, but his checkered past revealed a more stoic persona behind closed doors. During the Prohibition era he was a bootlegger and rumrunner in Cleveland. Soon he joined the illegal casino business in Kentucky and Ohio when Prohibition was repealed. He resorted to his wit and savviness to solve disputes, often hiring toughs to carry out his dirty work if needed.

Dalitz enlisted in the US Army in June 1942. Although he requested duty overseas to fight in a combat role, the Army used him in the Quartermaster Corps, citing his past expertise: The Dalitz family had a laundry business during Prohibition and used the laundry trucks to smuggle booze to Mexico and Canada. When he commissioned from a private to a second lieutenant, he served as the head of the Laundry Department in New York, coordinating with auto dealers to establish mobile laundry units across North Africa.

“I didn’t get overseas like I wanted to, but I did the next best thing, and I received a nice award for the work I did,” Dalitz later recalled in an interview. “It is considered to be a very coveted non-combatant award from the Second Service Command.”

George Barone

“I am a mongrel,” George Barone later told an interviewer who asked about his roots. “I’m partly Italian, Irish, and Hungarian.” Unlike the others on this list, Barone didn’t get into the organized crime game until after his service in World War II.

“I was in a war [World War II] with five invasions,” Barone, then 85 years old, said in court in 2009. “I killed a lot of people. I was in a [gang] war on the West Side of New York. A lot of people were killed on both sides.”

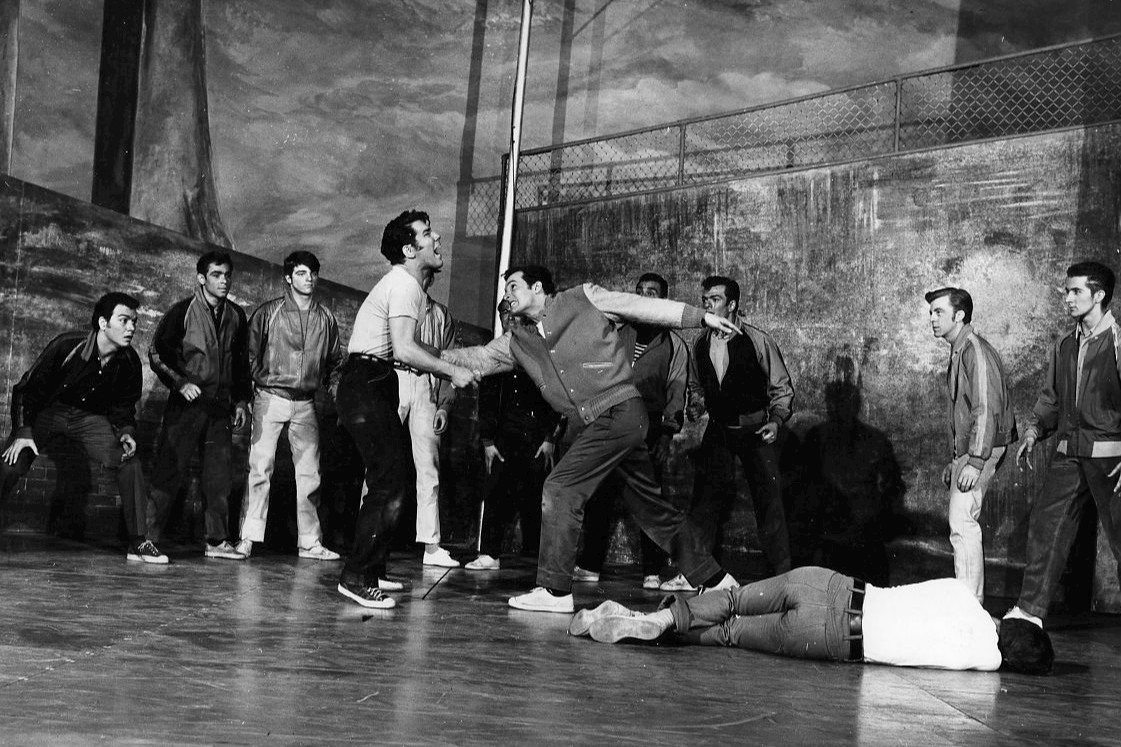

The former Marine war hero returned home from Iwo Jima to become a founding member of the Jets, the street gang made famous in the Broadway play and film adaptation of West Side Story. Barone rose to status as a made man, one of the toughest gangsters in the Genovese crime family, responsible for about 20 murders during his career as a wise guy. He was old-school and stuck to the code of silence, but that soon changed when he became one of three Genovese soldiers to rat on the family.

“I went bad,” Barone recalled, citing his new role as government witness. “I wanted to get even. I wanted to survive. I didn’t want to get killed by them [Vincent Gigante and the Genovese family]. I decided that the Mafia is not the paternal, wonderful organization that it proposes to be. The esprit de corps does not exist. Greed, violence, betrayal: that is what exists.”

Lucky Luciano

Among the most famous mobsters to serve in a US military capacity was Charles “Lucky” Luciano, an Italian ruffian who is often considered the modern father of organized crime in the United States. US naval intelligence officers launched Operation Underworld — a top-secret relationship with Italian organized crime families to counter Axis spies and saboteurs from infiltrating the homeland — and recruited Luciano from prison to assist in adding his broad network of lookouts to surveil New York harbors and report suspicions. Luciano was serving a 30- to 50-year prison sentence but was allowed visits from various associates to cooperate with the US Navy. Luciano’s contacts in the Sicilian Mafia proved useful during the Sicily invasion, where Navy intelligence officers collected maps of minefields, information from sympathetic Italians, and locations of code books.

These Italian contacts also assisted in Salerno in 1943 where the Americans discovered the location of a German railgun. The Port of New York remained secure for the entire duration of the war. Luciano filed a petition for executive clemency in 1945, and his former prosecutor and then-New York Gov. Thomas Dewey pardoned his sentence a year later in appreciation for his devotion during World War II.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.