A guy walks into a bar.

And when he walks out, he heads straight to Vietnam — but not to serve in uniform; he’s already been in the Marine Corps. (“I went in as a private and, four years later, I came out as a private.”)

His mission as a civilian is to bring a beer to active-duty, war-zone troops who hail from Inwood, a neighborhood at the top of Manhattan.

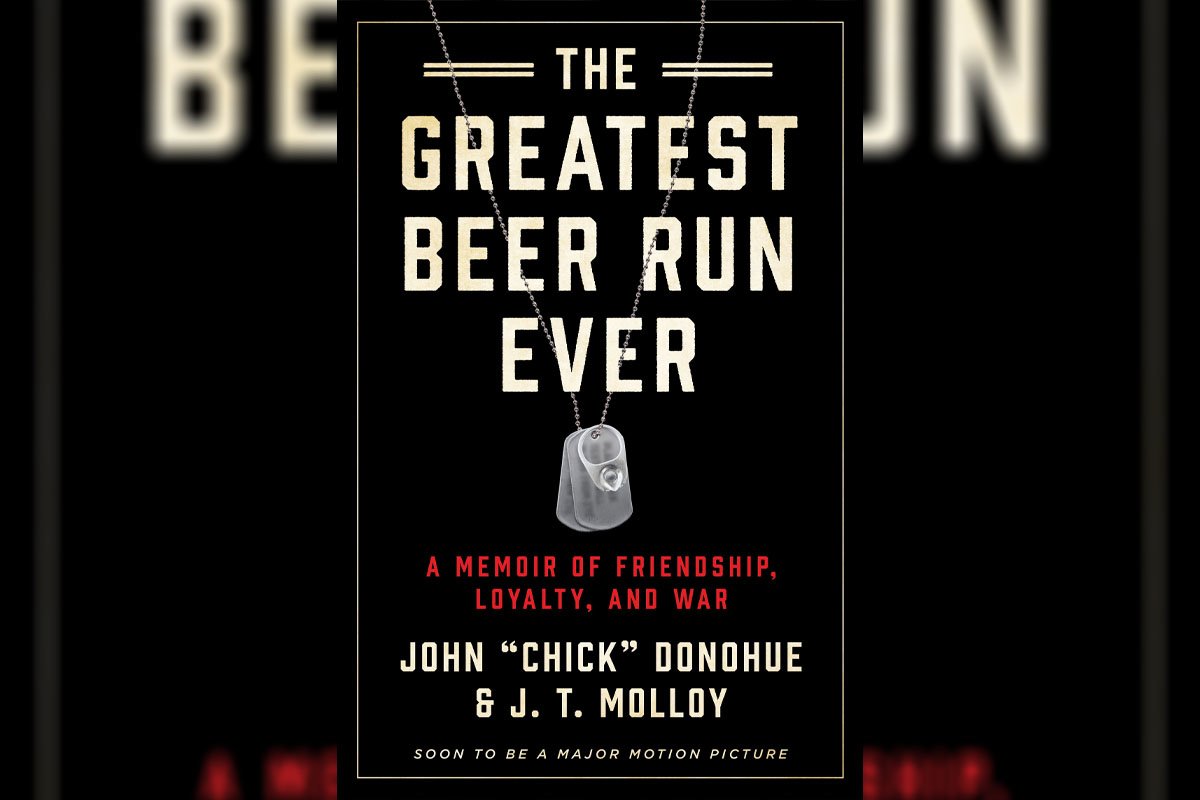

Call him and the idea crazy, and welcome to The Greatest Beer Run Ever: A Memoir of Friendship, Loyalty, and War by John “Chick” Donohue and J.T. Molloy. The premise seems preposterous, but the telling makes the story seem plausible and palatable.

Grab a beer or a coffee, and this book, and pull up a stool. John “Chick” Donohue, a young merchant seaman who can talk his way aboard a ship or a helicopter, narrates as though he is at Doc Fiddler’s pub, the birthplace of the misadventure.

In November 1967, Inwood has already buried 28 “brothers, cousins and friends who had been killed in Vietnam.” The neighborhood is a place in which “you didn’t have guys with a doctor friend of the family composing notes about nervous maladies or heel spurs,” Chick says — presumably in an allusion to the current commander in chief.

Conversely, Inwood doesn’t know “that our own brothers and sisters were among the protesters, and that Vietnam veterans would soon join them.”

The boys at the bar are convinced their neighbors now in Vietnam are demoralized by news reports about antiwar protests in the States. The drinkers resolve that somebody needs to pay a visit in ’Nam, and Chick is the designated traveler.

He heads to the maritime union hall and secures an immediate sea job, phones home (without mentioning his destination), buys a razor and socks for his duffel, and boards the World War II-era SS Drake Victory.

After two months of tending engines he arrives in Qui Nhon, where he persuades his ship’s captain to grant him leave. He receives three days to find boys from the ’hood including Rick Duggan, Tommy Collins, Kevin McLoone, and Bobby Pappas, the Greek among the Gaels.

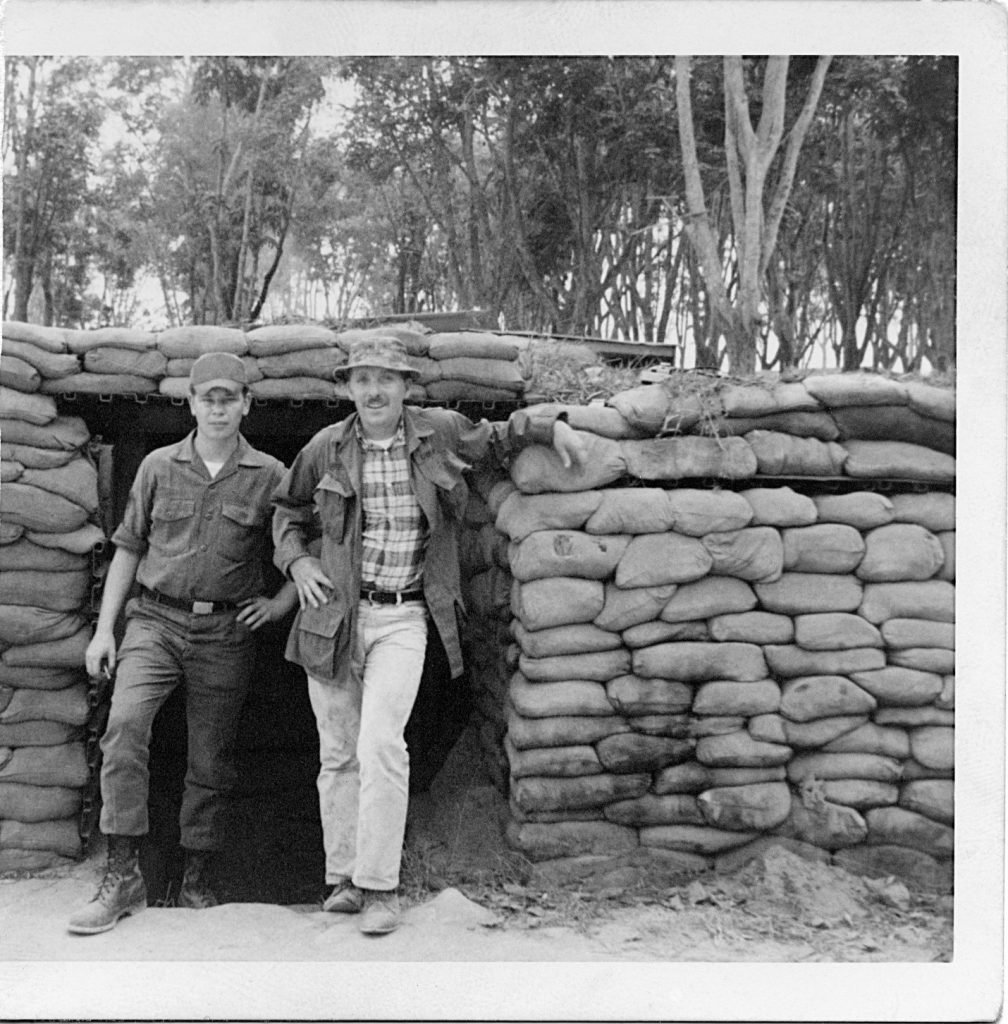

Unbelievably he instantly finds Collins, an MP on duty at Qui Nhon harbor. Later, at Collins’ base camp, an Army lieutenant treats Chick with deference. Why? “They think you’re CIA! Because why the hell else would you be here? In jeans and a plaid shirt, no less.”

Chick’s next task is to find Duggan at an airfield near An Khe. He thumbs a ride with three men in a Jeep. “Never pass an American,” says the driver, who turns his head to his new passenger in the back seat — and abruptly stops the vehicle.

“What the hell are you doing here?”

The guy behind the wheel is McLoone, an Inwood Marine. Two down, more to go. Next thing you know, Chick is in a foxhole while on patrol with Duggan and within earshot of — and then gunshot from — the North Vietnamese army. A touch of danger but visit accomplished.

However, his 72-hour leave now tallies 96 hours, and his ship has sailed. Without him. He has no change of clothes. Nor does he have a US passport, which he needs in order to get a South Vietnamese passport in order to leave Asia in order to get back to the US.

Four months later his visa is approved days before the Lunar New Year begins in late January 1968. The year-end “fireworks” he hears are not celebratory bursts. Rather, the North is invading the South during the supposed truce, and Chick, in Saigon, is inside the “tinderbox” of the Tet Offensive.

Worried about his buddy Pappas, now under fire, Chick goes to Long Binh “to make sure you’re okay.” He is, and in the wild Chick discovers firsthand that in Vietnam a guerrilla is not a gorilla.

His travels also show him the “official line” about Southeast Asia is inaccurate.

“What I was seeing did not jibe with the official reports {of success} out of our military command or out of Washington.” What a difference a foray makes.

By now you’re probably thinking Chick’s lit seems familiar, and it is:

- In 2015, Pabst Blue Ribbon funds a 13-minute documentary about an Inwood reunion where Pabst cans proliferate.

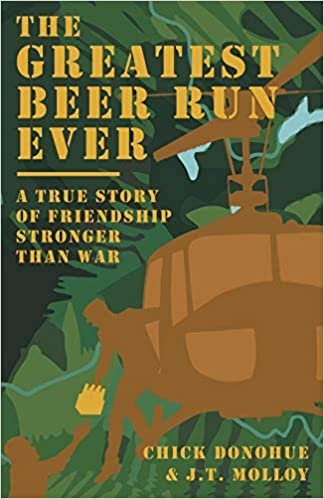

- Two years later, Donohue and journalist Molloy self-publish a paperback with the subtitle A True Story of Friendship Stronger Than War.

- Three years after, in a somewhat rare move in publishing, William Morrow prints the edition whose review you’re reading.

- Now a feature movie is in the works, directed by Peter Farrelly of the Oscar-winning Green Book. The Hollywood Reporter says Viggo Mortensen of Green Book and The Lord of the Rings has a role.

“Soon to be a major motion picture,” the book jacket proclaims, proof that familiarity breeds content in all forms.

The Greatest Beer Run Ever: A Memoir of Friendship, Loyalty, and War by John “Chick” Donohue and J.T. Molloy, William Morrow, 272 pages, $27.99. Available anywhere books are sold today.

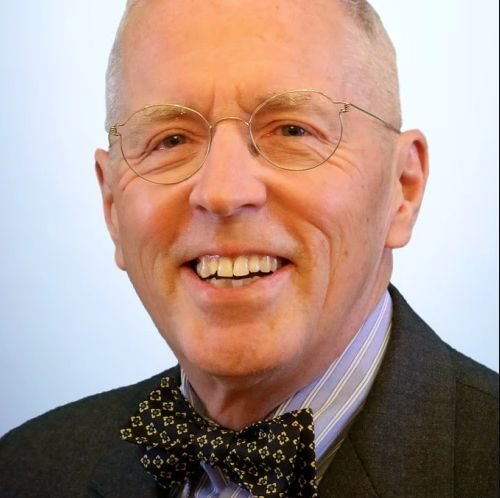

J. Ford Huffman has reviewed 400-plus books published during the Iraq and Afghanistan war era, mainly for Military Times, and he received the Military Reporters and Editors (MRE) 2018 award for commentary. He co-edited Marine Corps University Press’ The End of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (2012). When he is not reading a book or editing words or art, he is usually running, albeit slowly. So far: 48 marathons, including 15 Marine Corps races. Not that he keeps count. Huffman serves on the board of Student Veterans of America and the artist council of Armed Services Arts Partnership and has co-edited two ASAP anthologies. As a content and visual editor, he has advised newsrooms from Defense News to Dubai to Delhi and back.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.