Green Beret: ‘You Can Shit Your Pants Twice a Year Before You Lose Cool Points’

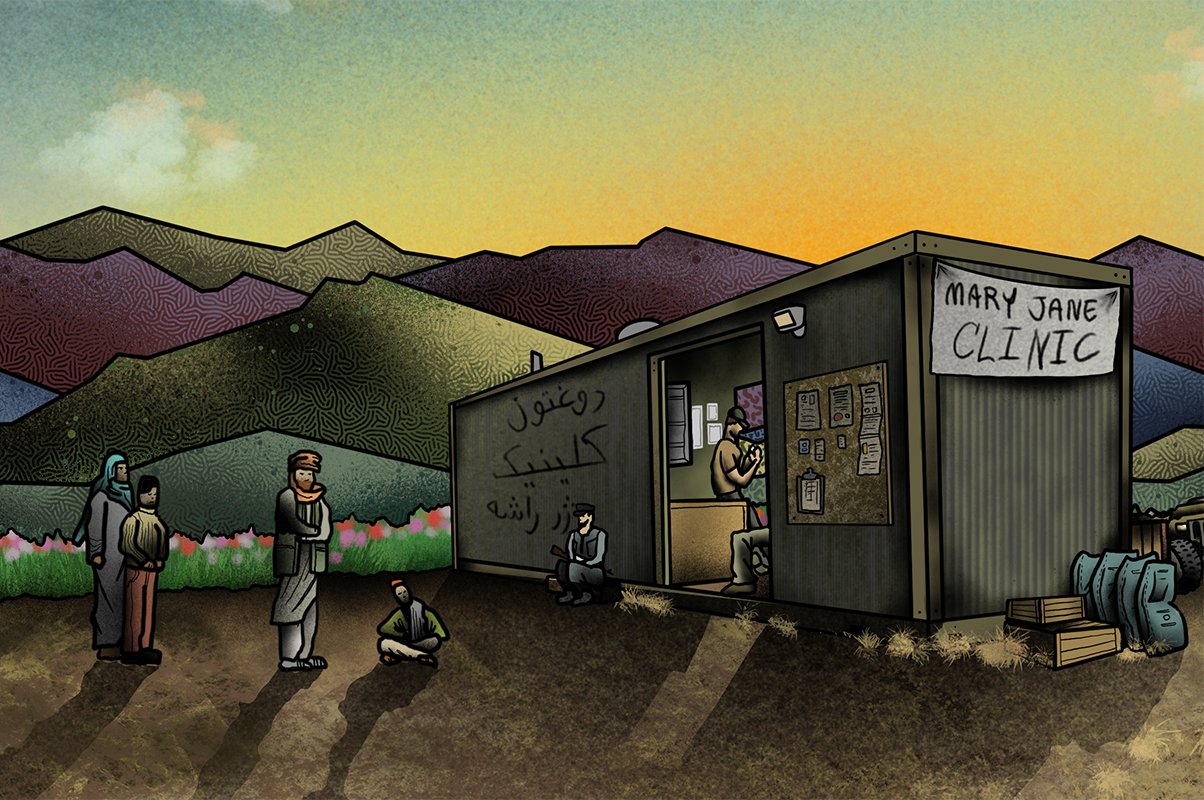

A steady diet of local food is sure to give the uninitiated digestive system some trouble. Illustration by Ben Cantwell.

I first met Willie Blazer in the Special Forces Combat Medic course at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, in 2000. Standing 6 feet, 2 inches, the Appalachian ginger sergeant told me in his North Carolina-meets-the-Tetons accent, “You can shit your pants twice a year before you lose cool points.”

While I had grown up under the assumption that even once was a no-go, a soothing Southern accent lends itself to persuasion, and Willie’s impressive background carried a lot of weight. He’d been a squad leader in 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, a wildland Hotshot firefighter, and a linebacker at the University of Montana. He seemed to know a thing or two, but I was skeptical about his pants-shitting maxim.

From July 2003 to July 2004, I was the medic for an SF team we nicknamed “The Damned.” We were a bunch of guys who would never hang out together given the option but were now sharing cramped living quarters and vehicles in life-or-death situations. We were assigned a contingency mission in [redacted]. A couple of high-level Northern Alliance generals/warlords were about to launch their armies at each other, and eight Green Berets were going to stop them and save Afghanistan, providing we didn’t kill one another first.

Quickly we learned that keeping peace between people who have already negotiated peace does not incur much danger. Boredom became our worst enemy, and to combat it, I busied myself with medicine. I had a shipping container delivered just outside the wire of our compound, and our team’s engineer helped me build it into a makeshift clinic. I visited a local pharmacy, made handshakes, and took home enough drugs to outfit it.

Although our little medical clinic was located right in the middle of a field of marijuana plants, I knew that a shipping container in a pot field next to a bunch of heavily armed operators was pretty uninviting — even for socialized health care. We needed signage. I employed one of my interpreters with the task.

“Mary Jane?” he asked me, seeking clarification.

“Yes,” I said with the air of a rookie Special Forces staff sergeant, completely out of uniform and kicked back on an ATV in a pot field in a third-world country.

“This is a woman’s name?”

“Yes.”

“Why do you name this after a woman?”

“It was a woman I was once very close with.”

“Yes. This is nice.”

He continued to scribe: Mary Jane Clinic.

As our deployment progressed, I later learned that dinner with a local — even one of high stature — did not come from a facility where kitchens are given a sanitation grade. In First Blood (Rambo), Col. Trautman famously describes how Green Berets eat things that “would make a billy goat puke.” I don’t know about all that, but on this outing, I ate a shit-ton of billy goat in various states of doneness. The menu was street meat kebabs, fresh vegetables, naan, and yogurt. This was essentially a game show called Wheel of Shit Your Pants.

As a rule, I avoid tuberculosis, and for this reason, I avoided the unpasteurized room temperature Afghan yogurt. You’d think vegetables would be safe, but have you ever seen what gardens are fertilized with in developing nations? Google “night soil.” Then look up at your nearest American flag, lock your body, render a salute, and thank God for modern American agriculture.

Naan, or bread, was always good, but its dryness was in competition with the MRE cracker. If you don’t have meat grease, you’ll think you’re choking. I’d like to solve the puzzle, Pat: “Street meat.”

We returned to our General Purpose Medium pot field compound, fat and full of hope for the new Afghanistan. We were all smiles as we stripped down to our various states of readiness and climbed into our Army-issued sleeping bags.

Two hours later, I was awakened by the whispering raspy voice of my weapons guy. “Doc, it’s your watch.” As I swung my feet over the edge of my cot and into my North Face hiking boots, I felt the thunder roll in my disturbed guts. I left the warmth of the tent and crunched across the gravel to the “American” shitter.

The Afghans are a beautiful people with thousands of years of culture. Their bathroom habits, however, have generally failed to evolve to anything that involves … sitting. Our hand-built three-seater outhouse was a new-and-improved iteration. We burned the prototype to the ground after our local force painted the insides like Jackson Pollock using a Ski-Doo. In the interest of national security, we built them a separate facility and placed a lock on ours. I felt for the lock in the dark and began to thumb the dials. Something felt different, not just in my guts, but in my hand. I flicked on the red light of the Petzl headlamp that lived around my neck. A new lock. With a new combo. Son of a bitch.

My guts growled at me. I thumbed the dials in desperation. Sweat began to bead on my forehead in the wintry air. I was a code breaker, and the entire allied offensive relied on my skills.

Bubble-bubble-rumble.

The air was aggressively moving its way through my guts. My medic’s brain pictured it moving through the gates: transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon … one more turn to Brown Town. None of the usual number combos worked. I yanked desperately on the lock. I tried to rip it off the Afghan wood. This must have been smuggled from Uzbekistan. For once, the Special Forces engineer had constructed something up to code.

Roughly 30 feet to my right was a break in the Hesco barrier that led to the weapons cantonment yard. I clenched my cheeks and walked on my toes, doing my best not to stumble over my untied boot laces or the uneven dried mud that made up the yard beyond the gravel. I button-hooked around the Hesco, threw my long johns around my ankles, squatted and leaned my back against the wire, cloth, and dirt barrier and let go.

The cold air bit at my bare cheeks, but the sudden relief inside me changed the perspective of my surroundings. The yard of T55 tanks and artillery pieces was a beautiful sculpture park backlit by millions of stars, unadulterated by city light or sounds. A vagal shiver waved through my body. For a moment, peace in Afghanistan.

The short-lived peace was quickly replaced with the realization I had nothing to wipe with. I back-shimmied up the Hesco to a standing position and gingerly replaced my long johns around my waist. Walking back to my tent, I substituted the strained and urgent clench walk for a very suspicious-looking bowlegged gait.

“Halt!” an Afghan soldier shouted in Dari, training his loaded AK-47 on my now empty guts. Suddenly my grandma’s sage advice to always wear clean underwear was echoing in my head: “The Lord could strike you dead at any moment, and the doctors don’t want to see your dirty drawers.”

Three months into my first deployment, I was about to die in a noncombat incident — cold, alone, and with a dirty ass. I imagined some hot nurse at the Combat Support Hospital receiving my body and having her day ruined by the realization that “This motherfucker shit himself.”

The Afghan soldier screamed excitedly, shining a flashlight in my face: “Fuck! Americani!”

I imagined the confusion the soldier must have felt as one of the four powerful Americans in his camp stood before him in black long underwear, hands high, legs bowed into a quarter squat. He said nothing else, lowered his rifle, and waved me on with his flashlight. I waddled to my tent, grabbed my baby wipes, and spared myself from having to count the incident against my annual pants-shitting freebies. Six months to go and still two in the bank. Cool points saved.

I saw Willie with his team some months later while passing through Jalalabad. I relished the knowledge that he had used one of his quota early in the deployment, while I still had both of mine. Pride is bad for karma. I would use both of mine in the coming months. A tale as old as Afghanistan itself. It is the graveyard of empires, cool points included.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2021 edition of Coffee or Die’s print magazine as “You Can Shit Your Pants Twice a Year Before You Lose Cool Points.”

Read Next: China’s Invisible-Laser Rifle is Basically a Milelong Lightsaber for Stormtroopers

Tyr Symank, who also writes under the nom de guerre Charlie Martel, is an Army Special Forces veteran, contractor, and occasional writer. He enlisted shortly after dropping out of journalism school and has since deployed worldwide as a Special Forces medic, operations sergeant, analyst, sergeant major, and tourist. He is the former director of the BRCC Fund and currently heads Black Rifle’s Free Range American channel. He is the worst sniper at Black Rifle Coffee Company.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.