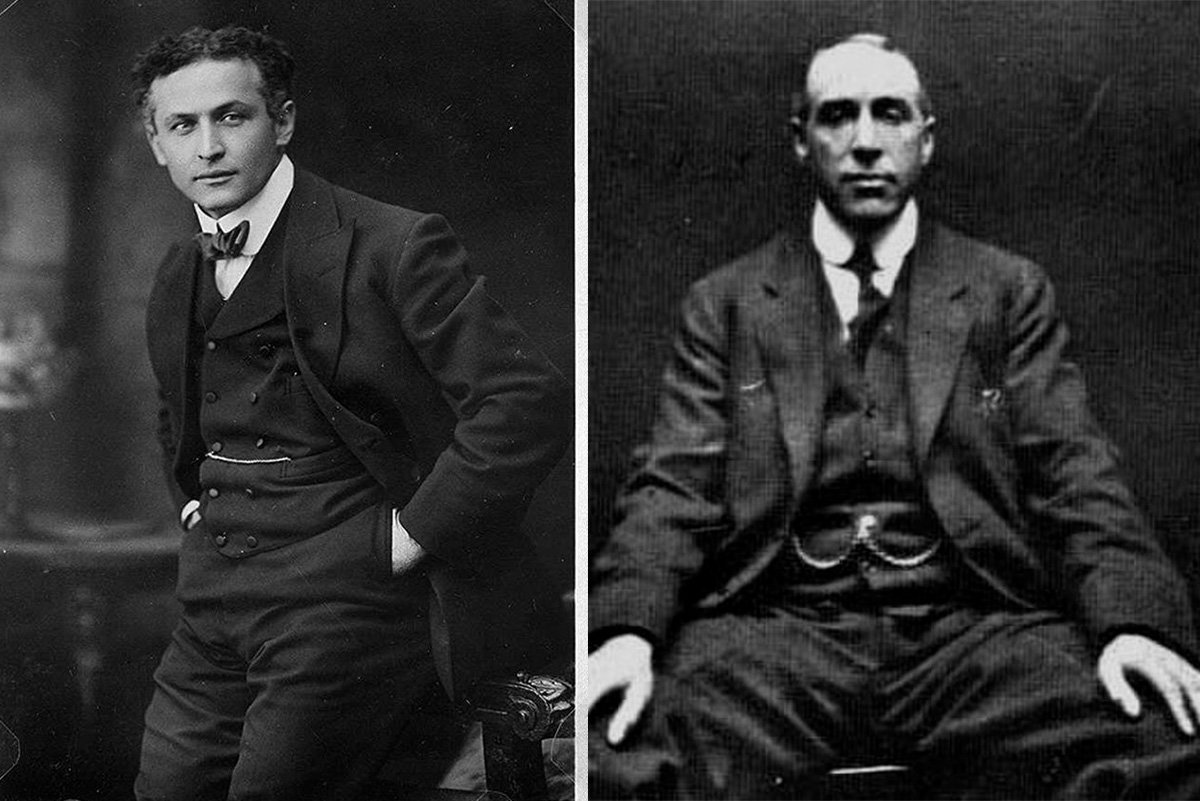

Two months before D-Day, authorities in London charged and arrested Scottish psychic Helen “Hellish Nell” Duncan with witchcraft, using a legal statute from the Witchcraft Act of 1735. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

As news of Blitz deaths hit the front pages of London newspapers in early April 1944, so did an odd story about a witch that clenched Winston Churchill’s jaw and almost sent cigar smoke pouring out of his ears.

Authorities in London arrested Scottish psychic Helen “Hellish Nell” Duncan and charged her with witchcraft, using a legal statute from the Witchcraft Act of 1735. It was the first time in a century the law had been used.

Duncan’s nickname, Hellish Nell, came from her knack for mischief rather than her psychic ability. As a child in Callander, Scotland, she exhibited a talent for contacting the “beyond.”

Amid the psychic trauma and grief from two world wars, many people flocked to spirit mediums, desperately hoping to communicate with their loved ones one more time. Duncan saw an opportunity in the desperation.

Duncan’s particular style of séance involved channeling spirits via her body. She entered a trance as the spirits possessed her physical form and communed with her audience members.

On some occasions, she produced “ectoplasm,” a feat many consider to be a physical manifestation of ghosts in the form of a substance. Harry Price, one of the first professional ghost hunters, later publicly discredited her accomplishment as simply vomiting silk or cheesecloth soaked in egg.

Price asked Duncan to submit to an X-ray to prove she was not hiding anything on her person. During the exam, she threw herself into hysterics, assaulted the nurses, and ran into the street — chased by her husband. After recovering, she allowed the X-ray to proceed, allegedly having passed her husband evidence during her episode.

Price’s investigation spurred several accusations of fraud during the early years of Duncan’s performances. But on May 24, 1941, Duncan performed a séance with the Scottish intelligence officer Brig. Roy C. Firebrace in the audience. She proclaimed — through her “spirit guide,” Albert, who was purported to inhabit Helen during her séances — that “A great British battleship has just been sunk.”

Firebrace, in touch with the admiralty in London, attempted to confirm the claim. British intelligence initially told Firebrace everything was fine, but hours later he learned Germany had sunk the HMS Hood, one of Britain’s best battleships.

The short-lived but heavily armed Kriegsmarine battleship Bismarck — the pride of the German navy out on its maiden voyage — sank the combat-hardened veteran Hood in the Denmark Strait with a direct hit to the aft magazines, igniting 112 tons of cordite into a 600-foot column of fire. There was no time to abandon the Hood, and just three sailors from the 1,418-man crew survived.

Months later, on Nov. 24, 1941, German U-boat 331 sank the HMS Barham with three torpedoes, causing a fire that blew its magazines in a massive explosion captured on film.

Because the Barham was an opportunistic assault, the U-boat commander was unsure if his torpedoes hit anything. Submarine commander Hans-Diedrich von Tiesenhausen reported to German high command that only one torpedo made contact with a Queen Elizabeth-class battleship, unaware that three — out of the four torpedoes fired — were direct hits.

After the sinking, Duncan conducted a séance in which she channeled a sailor, Sid, who died aboard the HMS Barham. The audience — unaware the sinking had occurred — was completely surprised by the news. Not even the Germans knew the Barham had sunk.

British authorities had chosen not to release news of the sinking. They classified the event as top-secret for almost two months to prevent the loss of British morale during a particularly dark period of the war.

The concealment served another tactical purpose: It prevented the Germans from knowing the Mediterranean fleet had suffered any casualties.

The enemy believed Britain’s Mediterranean bruisers still patrolled the Italian coastline. Weeks before the US would enter the war, Britain needed every advantage.

Whether by divine channeling from the other side or simply through leaked intelligence, Duncan’s predictions spooked the British government enough for it to watch her closely. The British Home Office, roughly analogous to the US Department of Homeland Security today, considered Duncan a fraud at best, but at worst — a German spy. Considering her prior fraud charges, Duncan knew too much to be considered innocent.

It took authorities more than three years to charge Duncan with anything, due in part to the unique nature of her alleged “crime.” Police and skeptics had long attempted to disprove Duncan’s abilities.

Authorities chose to indict her on a charge unseen for more than 100 years: witchcraft.

On Jan. 19, 1944, Portsmouth authorities arrested Duncan and imprisoned her in the Old Bailey in London. Her trial began in April, two months before D-Day. The timing sparked rumors that superstitious British authorities had arrested and charged Duncan because they feared she would reveal secret D-Day plans.

Found guilty after a dramatic trial, Duncan served nine months in jail. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called her conviction “obsolete tomfoolery.”

Duncan’s arrest and the political fallout from the absurdity of the charges ultimately helped change Britain’s laws. British Parliament repealed the Witchcraft Act of 1735 and officially recognized Spiritualism as a religion, making Duncan the last prosecuted witch of Scotland.

Read Next: 2 Men Exonerated for 1965 Murder of Malcolm X

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.