In 1917, the U.S. government gathered its brightest intellectuals — ranging from scientists and chemists to engineers and patriotic volunteers — and created what is referred to by historians as “The Manhattan Project of World War I.” The goal, unlike later years, was not a race toward the development of nuclear arms. Rather, it was a sprint to develop lethal chemical weapons for employment in the trenches of Europe.

In a race against time, technology, and science, a new and elite chemical warfare unit nicknamed “The Hellfire Boys” was established. They immediately began testing gear and creating alternatives to “the devil’s perfume.” Within 18 months, the U.S. developed the largest stockpile of chemical weapons in the world.

The First Use of “The Devil’s Perfume”

Chemical warfare was nothing new in the early 20th century. In fact, it had been around since as early as 600 B.C. when the Athenian military infused poisonous hellebore plants into the water supply of a stronghold located in the city of Kirrah. It later garnered the attention of France and Germany when the two countries agreed to sign the Strasbourg Agreement in 1675, which banned chemical weapons, particularly poisonous bullets. Indeed, armies have consistently used chemical weapons as a strategic tool for offensive psychological operations throughout history.

Despite the agreement (which had since gained more signatories from other European nations), Germany’s Fourth Army unleashed the first large-scale chemical attack on the French army during the Second Battle of Ypres in the spring of 1915. The surprise chlorine gas attack caught the French off guard, as they initially assumed it was a smoke screen to shield the enemy’s movements.

That assumption proved deadly. The French rallied and sent additional troops to support the incoming ambush just as a breeze picked up, pushing 170 metric tons of the poisonous gas toward French lines.The greenish-yellow cloud creeped slowly into every crevice of a 4-mile stretch on the battlefield, its distinct bleach smell reminiscent of the chlorine used in a swimming pool. The gas filled the lungs of the affected soldiers, squeezing the throat and causing an uncontrollable cough. The nose, eyes, and organs were next. Soldiers who inhaled higher volumes experienced a slow agonizing death by asphyxiation. In total, the German attack was responsible for killing 1,100 and injuring 7,000.

One German soldier, Willie Siebert, wrote about what he witnessed that day:

“All of the animals had come out of their holes to die. Dead rabbits, moles, and rats and mice were everywhere. The smell of the gas was still in the air. It hung on the few bushes which were left. When we got to the French lines the trenches were empty but in a half mile, the bodies of French soldiers were everywhere. It was unbelievable. Then we saw there were some English. You could see where men had clawed at their faces, and throats, trying to get a breath. Some had shot themselves. The horses, still in the stables, cows, chickens, everything, all were dead. Everything, even the insects were dead.”

The horrific display crippled morale but spurred a race to develop defensive measures that was unmatched by any other technological advancement seen at the time in the 20th century.

Building an Army Led by Science

The U.S. government realized they were largely unprepared for chemical warfare and immediately began allocating industrial and scientific resources to tackle the issue. Before the U.S. could send troops overseas to participate in the war, they needed to understand how to effectively fight it. The nation recruited its most gifted minds to craft deadlier chemical cocktails than the Germans. By the time the U.S. became involved in the war, German chemists and allied scientists were ping-ponging back and forth between offensive and defensive chemical warfare capabilities.

A chemist from Princeton named George Hulett enlisted to travel to France with the Bureau of Mines to investigate gas research and report his findings. He would later play a key role in assisting the Chemical Warfare Service by providing instant evaluation of battlefield reports and how to appropriately counter Germany’s advance along the western front.

Early on, the allies were using a tissue-like material drenched in urine and wrapped around their nose and mouth. This caused the gas to crystalize before it affected their system. The material supplied by Kimberly-Clark — a paper company that devoted its resources during cotton shortages to be used as an alternative for bandages — enabled soldiers a temporary solution to the complex problem. Today, it is known as Kleenex.

This invention born of battlefield necessity eventually lead to the first gas masks, which played a pivotal role in successfully countering offensive chemical warfare tactics on both sides. Unfortunately, the Germans stayed one step ahead of the allies as they sent their soldiers to analyze gas masks found on the dead bodies of ground troops before relaying the information back to their research teams. This led to improvements in gas mask filtration, thus reducing the brutal effects of chlorine gas. In response, the Germans introduced a newer colorless chemical agent called phosgene that was 18 times deadlier than chlorine.

After the Research Division and the Chemical Warfare Service were stood up in the fall of 1917, Vannoy Hartog Manning — then-director of Bureau of Mines — appointed George A. Burrell to chief of the Research Division; Burrell would go on to accelerate the development of chemical weapons. Chlorine and phosgene were already prevalent, but the allies were developing a new blister agent they would soon learn to fear.

Mustard gas was unlike anything used in the past because it lingered for months and was too heavy to be dispersed by a breeze. The Germans weaponized the new vapor to counter troops in gas masks. The gas wreaked havoc across the trenches, disfiguring allied soldiers with large and painful yellow blisters on their skin.

The Research Division recruited Harvard chemist James Bryant Conant to lead its dual capacity producing mustard gas as a part of its offensive chemical research strategy. Other engineers, including Frank M. Dorsey, developed counter-chemical measures, most notably the charcoal filters used in gas masks.

A large majority of these experiments took place at Camp American University Experiment Station — later known as “Mustard Hill” — in Washington, D.C., between 1917 and 1918. While the Research Division rushed to mass-produce mustard gas, they also tested the effects on the body at the Man Test House, enabling the allies to prioritize gear that could withstand battlefield abuse. Chemists and scientists would run members of Chemical Warfare Service through a series of stress tests and ultimately use the data to improve its weaknesses.

The Hellfire Boys

The War Department directed Captain Earl J. Atkisson to train, assist, and advise a new regiment called The Thirtieth Engineers (later known as the First Gas Regiment) at Camp American University in the fall of 1917. The first selected members were officers and enlisted men from the 20th Engineers — the largest regiment ever formed in the U.S. Army and later nicknamed “Fighting Foresters” for their contributions in France — because they had the manpower and engineering background. Working in tandem with the Research Division, the soldiers learned to use the portable “flaming liquid gun” (flamethrower), and studied how to deploy different types of chemical ordnance and protect themselves from injury.

Following the unit’s creation and fueled by civilian patriotism, the press put the word out in over 350 newspapers across the country requesting men between the ages 18 and 40 to volunteer for the Gas and Flame Battalion. One report from the Boston Transcript read, “The Hellfire Battalion offers a real chance for men to perform active service on the battlefront. They will go to France earlier than any other commands and they will be at the head of the great offensive which will supposedly open in the spring.” Among the ranks were 30 chemists, 12 French interpreters, 12 electrical experts, 10 gas experts, eight gas engineers, and a small team of about 60 support personnel. These men of the newly established Hellfire Battalion called themselves “The Hellfire Boys.”

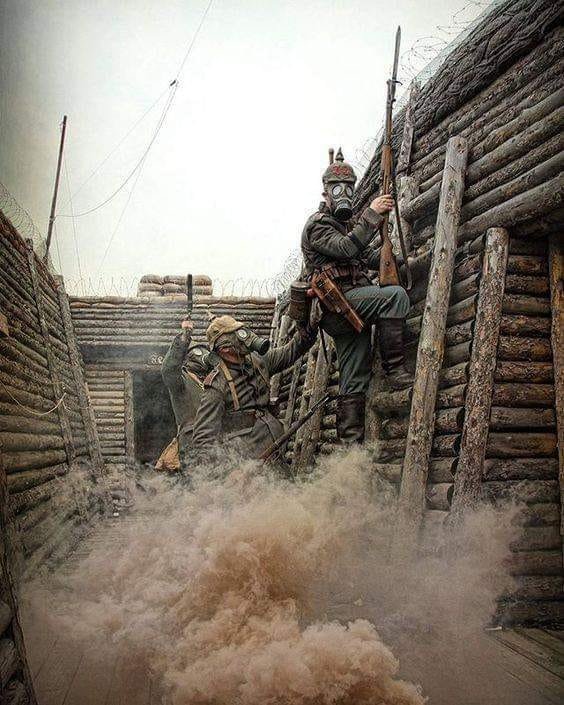

The Hellfire Boys employed “shows” or smoke screens to advance troops from the trenches into No Man’s Land, often doing so while carrying more than 100 pounds of gear.

The Hellfire Boys deployed to France and began a complex training cycle with their British counterparts in the beginning of 1918. They learned how to operate the 4-inch stokes trench mortar and the livens projector — two British mortars that were often buried alongside hundreds of others that could launch gas projectiles three football fields away. Ultimately, they were the sponge learning the bloody lessons the Brits experienced during gas warfare and were on a fast track to provide their limitless resources to the battlefront.

Gas warfare was as laborious as it was strategic. Many operations were cancelled because of the weather. The Hellfire Boys, supported by infantry soldiers, played a role in the Chateau-Thierry Campaign and later proved their effectiveness in many of the major offensive battles in the fall (St. Mihiel and Argonne-Meuse). The Hellfire Boys employed “shows” or smoke screens to advance troops from the trenches into No Man’s Land, often doing so while carrying more than 100 pounds of gear. The men soon experienced the terrifying whine of an incoming shelling paired with sporadic but accurate machine gun fire. When approaching an occupied trench, shows would be accompanied by thermite bombs to disperse troops.

When the lines were stationary and preparing for an assault, engineers carried the mortars and projectors through pitch dark and damaged pockets of large, muddy holes from the previous day’s weather downpour. The canisters were filled with gas, thermite, smoke, and high explosives, thus making the transport much more risky.

The Mousetrap and Late Developments

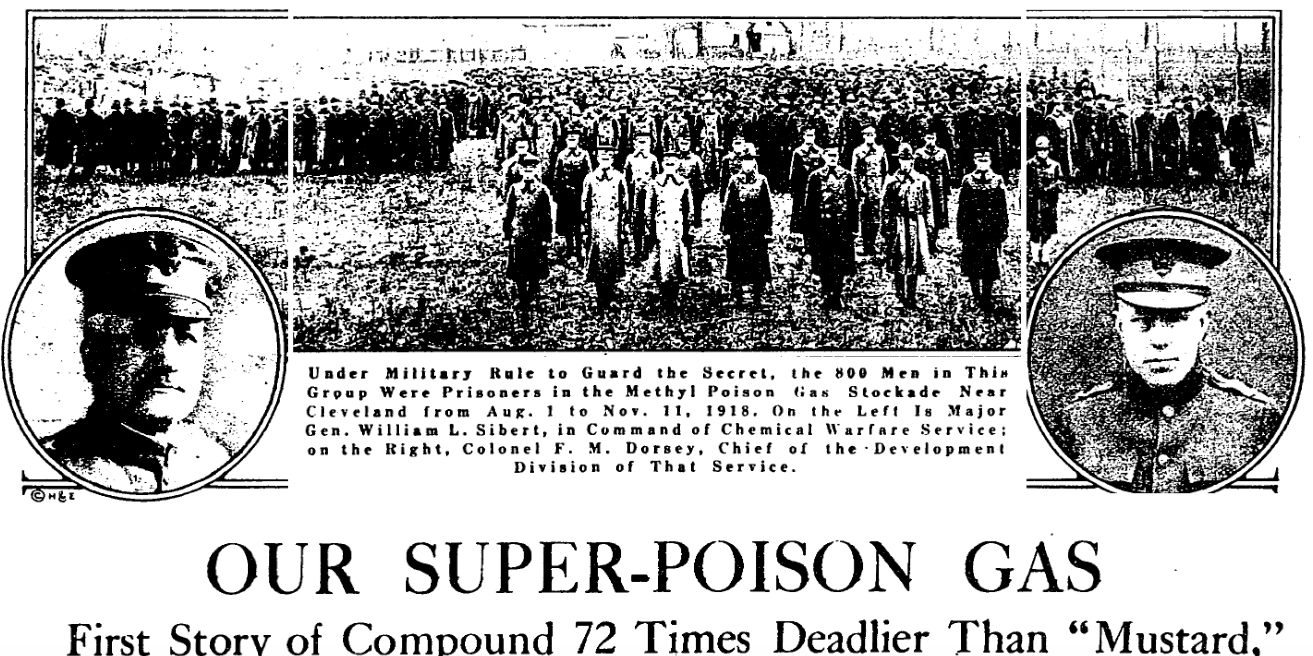

In July 1918, the Chemical Warfare Service believed it could change the tide of the war and began manufacturing at a top-secret lewisite plant in Willoughby, Ohio. Conant and Dorsey helped set up the facility, which was nicknamed “The Mousetrap” because no one that went in came out until after the war ended.

Lewisite is much like mustard gas in that it doubles as a blistering agent and irritant, but its real horror lies in the way it is delivered. Unlike mustard gas, lewisite can be used in liquid form, potentially targeting the water and food supplies of a densely populated area. According to Harper’s Monthly, lewisite “is highly explosive, and on contact with water it bursts into flame. Let loose in the open air, it diffuses into a gas which kills instantly on the inhalation of the smallest amount that can by any means be measured. A single drop of the liquid on the hand causes death in a few hours, the victim dying in fearful agony. The pain on contact is acute and almost unendurable. It acts by penetrating through the skin or, in the gaseous form, through the lung tissue, poisoning the blood, affecting in turn the kidneys, the lung tissue, and the heart.”

The Mousetrap created this nasty super-poison gas with the intention of weaponizing it for use against the Germans, but the war ended before it could be used. The lewisite was disposed of in the ocean, 50 miles off the coast of Baltimore where the ocean is 3 miles deep. The Harper’s article noted that the sea water was expected to neutralize the chemical.

Research Division developed other equipment that never saw use in the war, including mobile gas tanks that were carried like a backpack and would have eased the delivery of gas agents — in previous years, it was labor-intensive and depended on weather conditions for release. This would have significantly aided small units during their offensive assaults.

Today, the unit is under the helm of 2nd Chemical Battalion and has since participated in World War II, the Korean War, Operation Desert Storm, and the Global War on Terrorism.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.