The American Private Who Died in the Final Minute of World War I

Men of the 64th Regiment, 7th Infantry Division, celebrate the news of the armistice, Nov. 11, 1918. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

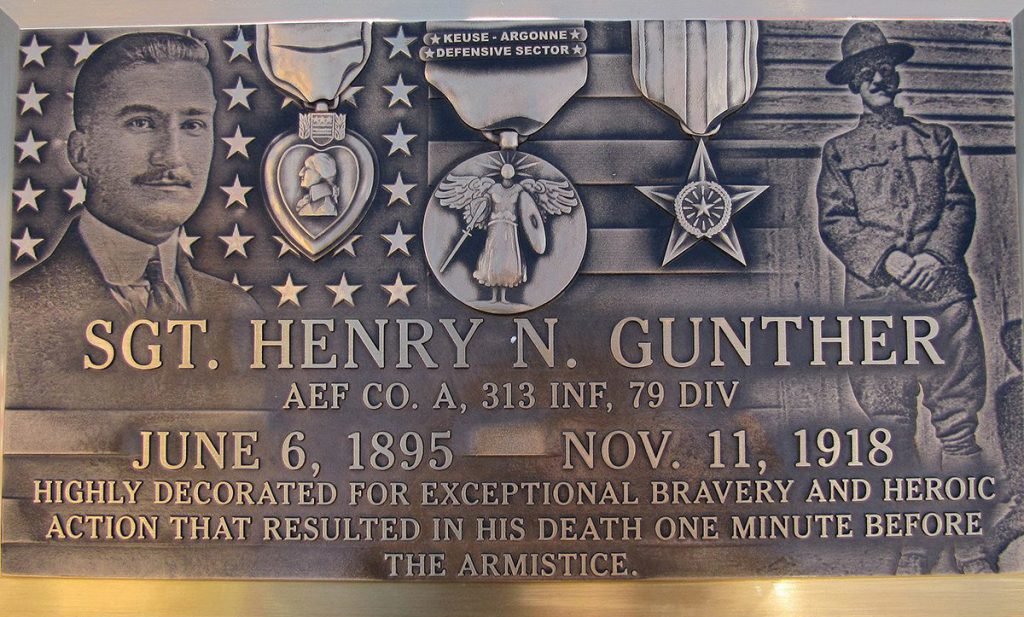

In the final instants before the guns fell silent on the 11th hour of Nov. 11, 1918, near the French village of Ville-devant-Chaumont, US Army Pvt. Henry Gunther became one of the last known soldiers to die in World War I.

Feeling he still had something to prove in order to reclaim his honor, the 23-year-old German American from Baltimore had fixed a bayonet to his rifle and charged through dense fog to assault a German machine-gun position. He was killed in action at 10:59 a.m. — one minute before the armistice went into effect.

Some 16 minutes before his final charge, word of the armistice had traveled along the Western Front and reached Gunther’s position. Along with other members from Company A, 313th Infantry Regiment, 79th Infantry Division — a US Army unit affectionately known as Baltimore’s Own — he’d learned that the armistice scheduled for 11 a.m. was to be honored.

While soldiers on both sides of no man’s land waited for the war to end at last, Gunther refused to accept its inevitable conclusion. Sixteen minutes was certainly enough time to change his image in the eyes of his fellow doughboys, he thought.

Before the war, Gunther was born to German immigrant parents and worked as a bank teller. He had a promising career and a life to share with a new fiancée. When the US Army called for military service, however, Gunther enlisted as a supply sergeant and sailed to France in July 1918.

He soon penned a letter back home describing the horrors of trench warfare. An Army censor intercepted the letter, and as punishment for his defeatist beliefs, Gunther was demoted to the rank of private. When his fiancée found out about the demotion, she broke off their engagement.

The demotion and heartbreak crippled Gunther’s morale. His German ancestry also did him no favors among his American peers; he had to go the extra mile to earn respect from others in his unit. With his reputation in shambles, Gunther fought to regain his glory at every opportunity.

In September, Gunther’s company fought during the Meuse-Argonne offensive at a hill called Montfaucon.

“Germans were constantly infiltrating and cutting our ground phone lines,” Sgt. Ernest Powell, a friend of Gunther’s who served in the same unit, wrote in The Baltimore Sun. “To insure messages getting through, we set up [a] runner system. Carrying messages was hazardous because of enemy snipers. We worked it on a volunteer basis.”

A regimental runner asked for volunteers to run messages between regimental and brigade headquarters. Gunther stepped forward to take the job. For a week straight, Gunther ferried messages between positions. After being shot in the hand by an enemy sniper, he bandaged his wound and remained in action.

Following the fateful morning of his death, Gen. John Pershing, the American Expeditionary Forces commander, declared Gunther to be named the last American killed in action. Gunther, however, wasn’t the only soldier to fall that day. In fact, in the six hours between the signing of the armistice and its enactment, Gunther was just one of at least 2,738 troops and 320 Americans to be killed, Joseph Persico wrote in Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour.

“He probably felt shamed by his demotion to private and felt this somehow dishonored his family,” Gunther’s great-niece Carol Gunther Aikman told The Baltimore Sun. “He was trying to redeem himself, and when shots rang out, he alone raced forward. I believe his final resting place, Most Holy Redeemer Cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland, is perfectly named for what he was trying to accomplish.”

Read Next: Why Germany Wanted To Ban America’s Pump-Action Trench Shotgun During World War I

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.