My Wife is a Nurse on the Front Lines of the Pandemic — and My Hero

COVID-19 has taken the world by storm. To date, 3,758,421 cases have been confirmed worldwide. The death toll is at 259,513, though these numbers are changing by the hour. Nurses are on the front lines, fighting for every one of those lives at great risk to their own. As “the curve” seems to be flattening, their hard work and sacrifice seems to be paying off.

But in many parts of the country, the fight against coronavirus still rages.

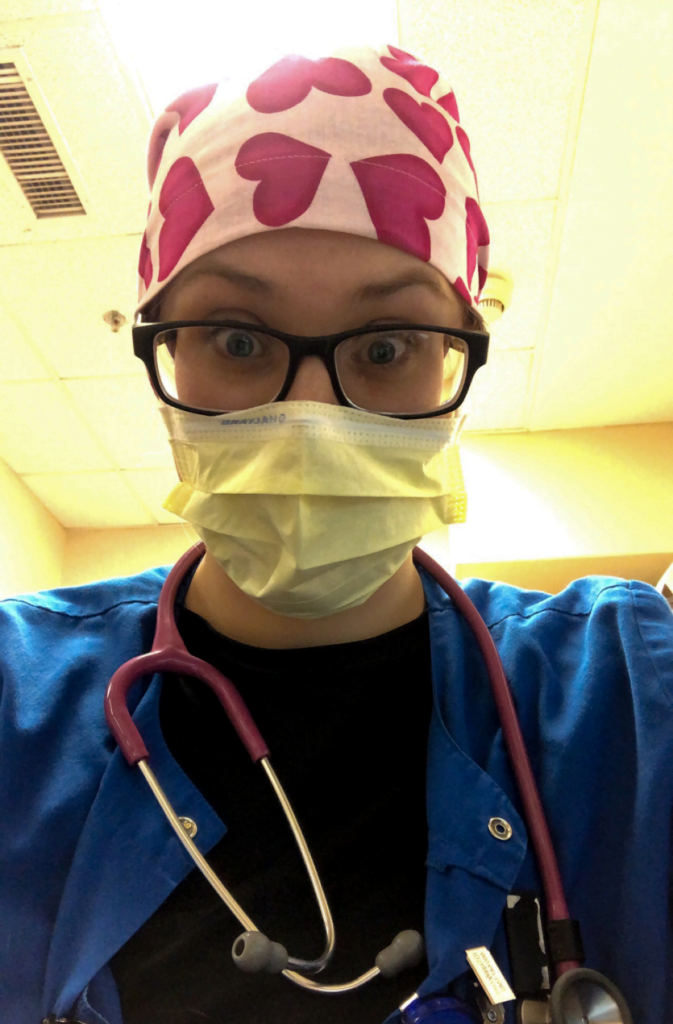

As a paramedic, I have had the privilege of working with an amazing group of nurses in Minneapolis for the last four years. In fact, I’m married to one. I have seen how hard she works for her patients under normal circumstances, and I’ve had a front-row seat to the devastating impacts the pandemic has wrought on my wife and everyone she works with.

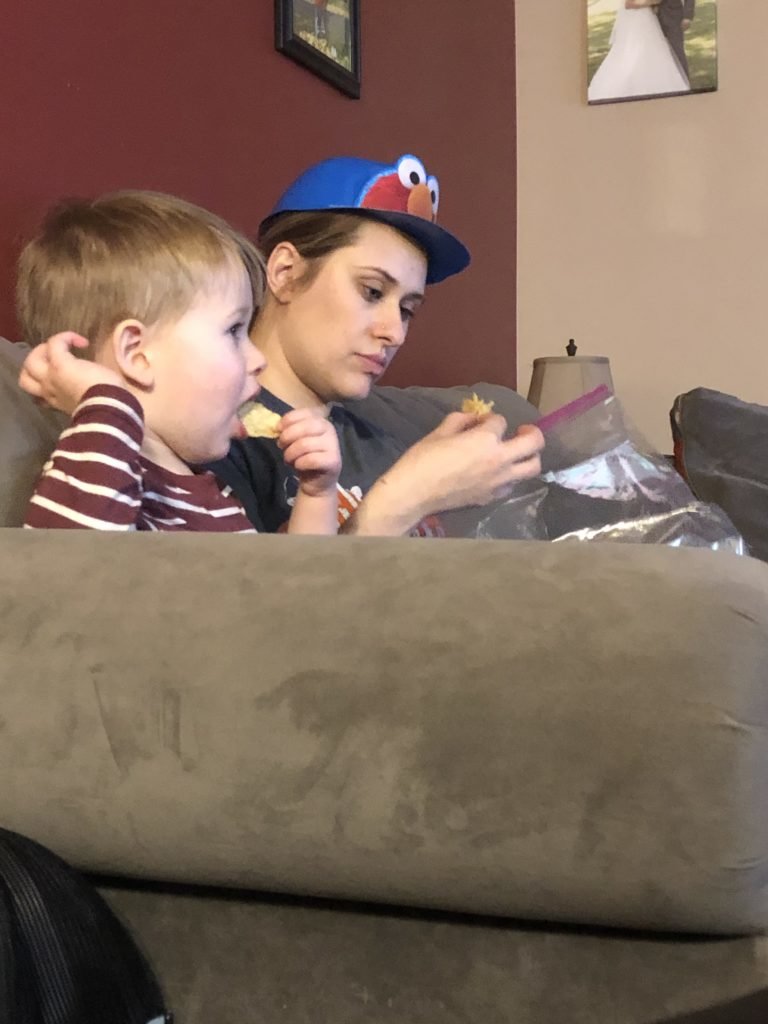

I married Rhiannon in 2016, and she has been a shining light in my life since the day we met. She brought our two beautiful children into the world, and even before this crisis, she regularly worked 12-hour shifts on top of her parenting duties. When news of the virus first broke, we discussed the ominous information that was loosely available at the time. We talked about what we should do if we contracted the virus and how to protect our young kids.

We made decisions that immediately altered our daily rhythm, including decontaminating in the garage and taking as few items to and from work as possible. The fear of us potentially bringing the virus home to our kids was terrifyingly palpable. This was new territory. We didn’t — and still don’t — know what lies ahead.

In the beginning stages of the virus, things were changing drastically at the hospital where Rhiannon works. Some of the initial protocols with Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) didn’t seem to align with the guidelines set forth by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). My wife’s fear was escalating, as I’m sure every other medical professional was experiencing.

At first, the hospital had a sharp decrease in patients. The reduction of elective procedures and the fear reverberating through the public left only severe or critical patients coming into the hospital. This resulted in the hospital offering on-call shifts or leaves of absence (LOA) for nurses on shifts that were overstaffed. Initially, my wife took advantage of that to reduce her exposure — we have a newborn infant at home, after all.

Eventually her rotation came up. She kept telling me that she missed going into work and taking care of people, but the fear of bringing harm to our kids outweighed that. But the time came for her to face the reality of the pandemic face-on.

“I’ve never been so nervous to go to work,” Rhiannon told me before that first shift back. The fear was clear on her face, and she was concerned. My wife has asthma, and although we had heard that breathing issues can make you more vulnerable if exposed to COVID-19, she wasn’t worried about herself. She wanted to keep our family safe, but she also wanted to do what she loves: taking care of people and helping them get healthy.

Her shift went without a hitch, and she came home late that night. She stuck with the plan we agreed on and stripped all her work clothes off in the garage and decontaminated her car and anything she touched. She threw her clothes into the washer and started it right away, followed by a shower. For a mother anxious to hug her children after a 12-hour hospital shift, this 40-minute decontamination process on top of the 90 minute commute was grueling. But the abundance of caution was necessary to keep our family safe.

My wife laid in bed that night, like every night before, wide awake with concern over bringing the virus home. The threat was real, and she’d seen it firsthand.

Nurses have a unique strength that allows them to walk into these types of dangerous environments and face an unseeable enemy head on. Rhiannon, alongside her fellow nurses, possesses an intestinal fortitude that is uncommon these days. She has no concern over the fact that she could contract the virus — she only thinks of others.

Rhiannon has since continued with her shifts, navigating the nonstop changes to PPE standards and other various protocols. Her hospital has ranged from having 10 percent to 20 percent of all COVID-19 patient cases in Minnesota. The more patients that come in, the greater danger of contracting the virus. My wife’s anxiety has never been higher, but her fellow nurses have helped ease it. This burden would be impossible to shoulder alone.

Many of my wife’s co-workers who are single or don’t have kids have been volunteering to work on the floors that are only taking COVID-19 patients. This has helped alleviate some stress, but the threat of COVID-19 still looms heavy. Rhiannon is a float registered nurse, which means she is trained to float to different floors of the hospital instead of specializing in just one area, allowing her to work anywhere the hospital is short staffed. It’s common for her to go from non-COVID floors to the COVID floors, sometimes bouncing back and forth in the same shift.

The truly awe-inspiring part of all of this is that I know she’s not the only one facing this daunting medical crisis. Healthcare professionals around the world are exposed to the virus day in and day out. Many of them have families waiting for them at home. Some have chosen to send their significant others and children to stay in the homes of other family members, or have decided to stay in hotels in isolation. Some never will never get the chance to see their family again. But they are what stands between the public and this virus. They are the ones putting their blood, sweat, and tears into saving as many people as possible.

But not everyone can be saved, and that’s a reality that can’t be avoided. Densely populated areas like New York City have been especially impacted. The morgues are full, and FEMA’s makeshift facilities are filling up rapidly. These facts of the pandemic are always on Rhiannon’s mind, as well as mine. I honestly don’t know what I would do without my wife, but I understand her desire to serve the public. This is the war that will define her generation of medical professionals, and someday I’ll tell our grandkids about how their grandma fought bravely on the front lines.

Joshua Skovlund is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die. He covered the 75th anniversary of D-Day in France, multinational military exercises in Germany, and civil unrest during the 2020 riots in Minneapolis. Born and raised in small-town South Dakota, he grew up playing football and soccer before serving as a forward observer in the US Army. After leaving the service, he worked as a personal trainer while earning his paramedic license. After five years as in paramedicine, he transitioned to a career in multimedia journalism. Joshua is married with two children.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.