The Definitive List of Every Hispanic American Medal of Honor Recipient…Ever

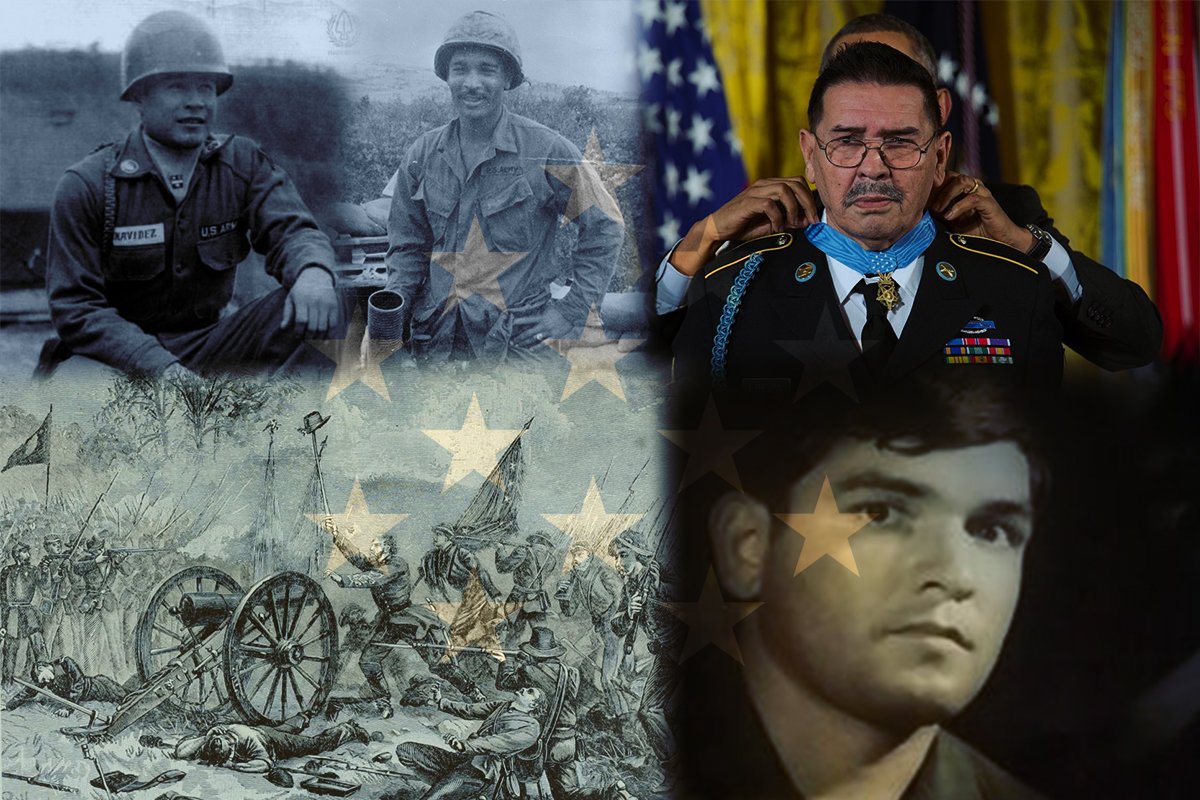

Sixty Hispanic Americans have been awarded the nation's highest military honor for valor, the Medal of Honor. Composite by Coffee or Die.

National Hispanic Heritage Month began on September 15 and lasts until October 15.

Throughout history, Hispanic servicemen have faced discrimination in the form of racism, segregation, and language barriers. It was sometimes difficult for them to feel a sense of belonging in the military, and they were often not properly recognized for their sacrifices. However, their brothers-in-arms witnessed their actions overcoming insurmountable odds.

In 2002, Congress reviewed several Hispanic award citations to uncover whether they were worthy of an upgrade. President Barack Obama awarded 24 additional veterans, bringing the total to 60 Hispanic recipients of the Medal of Honor (MOH), the U.S. military’s highest award for valor.

These hometown heroes — some who are immortalized by plaques and statues, others who silently rest in their grave with a modest tombstone — all braved insurmountable odds against a determined enemy. They conducted lone assaults on enemy bunkers, led harrowing rescue attempts, fought hand-to-hand combat engagements, and selflessly made themselves the intended target to save others. The Medal of Honor is often awarded when death is imminent, and many receive the award posthumously. Here are their stories.

American Civil War

Ordinary Seaman Philip Bazaar

Bazaar was an immigrant from Chile and served in the U.S. Navy aboard the USS Santiago de Cuba as it assaulted Fort Fisher on Jan. 15, 1865. Fort Fisher was the last coastal stronghold of the Confederacy and a strategic trade route in Wilmington, North Carolina. The fortress obtained the nickname “The Southern Gibraltar” for its strength; it was a prime target for the Union to cripple their foes.

During the Second Battle of Fort Fisher, Bazaar, alongside six other men, assaulted from the shores to the beachhead leading into the fort. As Navy warships that sat in the cove of Cape River and bombarded battery defenses, Bazaar helped secure victory and contributed to the battle that was a turning point in the war.

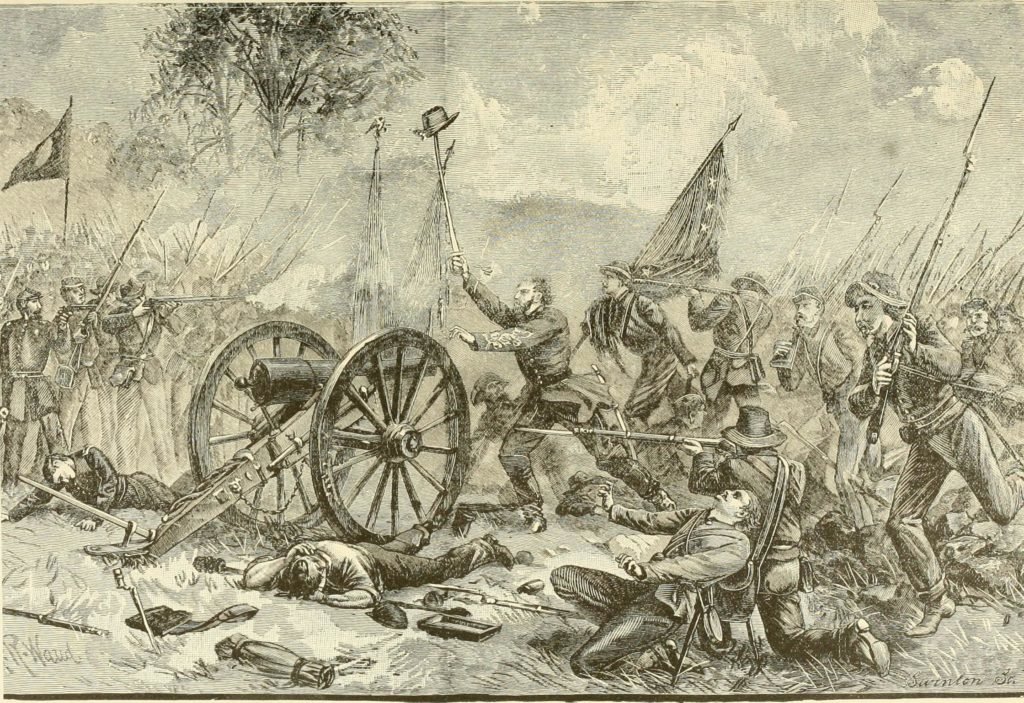

Corporal Joseph H. De Castro

Boston native Joseph H. De Castro joined the all-volunteer 19th Massachusetts Infantry as a corporal in his 40s. He didn’t carry a rifle, but as a brawler from Boston who carried the flag of Massachusetts, he was the weapon. His unit saw action during the Battle of Gettysburg, and he personally participated in the last effort famously known as Pickett’s Charge.

Bearing his flag, De Castro sprinted, zeroing in on the Confederate flag bearer from the 19th Virginia Regiment. As flagmen, they helped lead advancing forces by waving it bravely as bullets whizzed by their heads and cannonballs exploded at their feet. The pair fought, but De Castro successfully captured their flag, allowing his troops to rally and push into the castle. Notably, De Castro was the first Hispanic-American to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

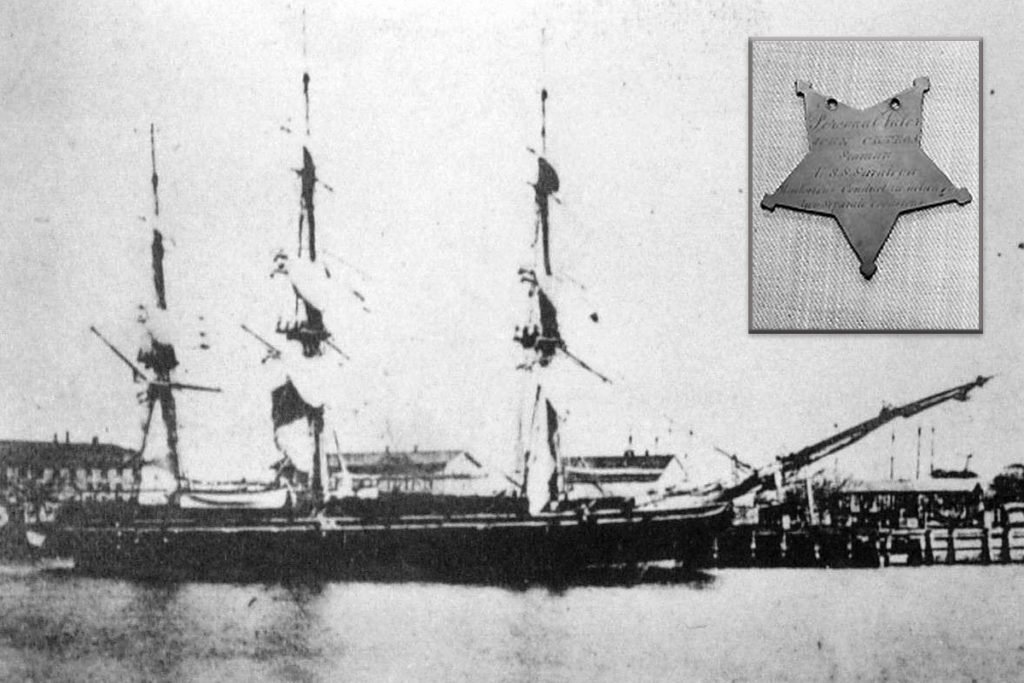

Petty Officer John Ortega

Like fellow American Civil War veteran Philip Bazaar, John Ortega was an immigrant. Born in Spain as Juan Ortega, he eventually immigrated to Pennsylvania. He served with the U.S. Navy aboard the USS Saratoga, a sloop-of-war battleship with a ship-rigged design. Up to 20 cannons could attack at close range with ferocious firepower. Ortega’s role was to be a raider — to kill and capture as many Confederate soldiers as possible to help contribute to the larger Union blockade mission in South Carolina.

His Medal of Honor citation is vague and doesn’t describe what he and his other seamen accomplished in the winter of 1864, but one report reads: “Ortega was a member of the landing parties from the ship who made several raids in August and September which resulted in the capture of many prisoners and the taking or destruction of substantial quantities of ordnance, ammunition, and supplies. A number of buildings, bridges, and salt works were destroyed during the expedition. For his actions Seaman John Ortega was awarded the Medal of Honor and promoted to acting master’s mate.”

Boxer Rebellion

Private France Silva

Silva was the first Hispanic U.S. Marine to be awarded the Medal of Honor and the only Hispanic recipient at the turn of the 20th century in 1900s China for his role in the Boxer Rebellion.

“As a part of a contingent of Marines from the USS Newark, Silva assisted in defending the British legation in Beijing until its relief by the Allied Army,” one report reads. The China Relief Expedition involved the USS Newark and USS Monocacy parked off the shores of Taku Bar, while Marines and blue jackets launched a beach assault to retake the city of Tientson from the Boxers who lay siege to the legation. Through “meritorious actions,” Silva was awarded for distinguishing himself.

World War I

Private David B. Barkley

David Bennes Barkley was born in Laredo, Texas, in 1899. At 17 years old, Barkley enlisted in the U.S. Army following in his father Josef’s footsteps. He was sent to France during World War I. Barkley’s commanders needed bodies, and if one of their soldiers’ identities was compromised to reveal their Hispanic heritage, they would be sent home, so they kept it a secret. Barkley served with the A Company, 356th Infantry, and on Nov. 9, 1918, volunteers were called to conduct a reconnaissance patrol across the Meuse River.

Two soldiers raised their hands — one of them was Barkley, the other was a soldier named Harold Johnson. The pair crept into the water and swam to the German side. They scouted enemy fighting positions, and when they had gathered enough information, they turned back. But as they were returning to their side, the Germans spotted them and opened fire. As he was swimming and trying to avoid gunfire, Barkley’s body cramped up; he couldn’t keep his head above the water, and he drowned. His family believes he was fearful that his Mexican descent would be discovered, so he put himself in harm’s way to prove that he belonged. For his sacrifice, General John Pershing awarded him the highest medal for valor. In 1921, his body was reunited with his family, and an elementary school in San Antonio was renamed in his honor.

World War II

Staff Sergeant Lucian Adams

The Adams family was patriotic in every sense of the word — eight of Lucian Adams’ brothers served during World War II, and all returned home in one piece when it ended. Before the heroic actions that earned him the Medal of Honor, Adams fought in Italy with the 3rd Infantry Division. They assaulted Anzio Beach, and Adams destroyed a machine guns’ nest. He received the Bronze Star and Purple Heart during the attack. However, it was a lone assault through the Mortagne Forest — during which he was described as “like a tornado” — on Oct. 28, 1944, near St. Die, France, that got him nominated for the MOH.

A portion of his citation reads: “Although his company had progressed less than 10 yards and had lost three killed and six wounded, SSgt. Adams charged forward dodging from tree to tree firing a borrowed BAR from the hip. Despite intense machine-gun fire which the enemy directed at him and rifle grenades which struck the trees over his head, showering him with broken twigs and branches, SSgt. Adams made his way to within 10 yards of the closest machine gun and killed the gunner with a hand grenade. An enemy soldier threw hand grenades at him from a position only 10 yards distant; however, SSgt. Adams dispatched him with a single burst of BAR fire. Charging into the vortex of the enemy fire, he killed another machine gunner at 15 yards’ range with a hand grenade and forced the surrender of two supporting infantrymen. Although the remainder of the German group concentrated the full force of its automatic-weapon fire in a desperate effort to knock him out, he proceeded through the woods to find and exterminate five more of the enemy. Finally, when the third German machine gun opened up on him at a range of 20 yards, SSgt. Adams killed the gunner with BAR fire.”

Private Pedro Cano

World War II veteran Private Pedro Cano was posthumously awarded the MOH in 2014. Cano was born in La Morita, Mexico, before moving to Texas when he was two months old. When he was old enough, he enlisted in the Army’s 4th Infantry Division, commonly referred to as the “Ivy Division” for its unique shoulder patch. Cano fought for his right to belong despite the fact that he was not a U.S. citizen. He delivered as a teammate and a warrior.

The months-long fight in the Hürtgen Forest, located on the border of Germany and Belgium, is often remembered as the worst defeat in the U.S. Army’s history. But it was Cano’s proving ground. On Dec. 2, 1944, German machine gunners talked their weapons from the high ground and suppressed an American infantry offensive. Armed with a shoulder-fired rocket launcher, Cano crawled alone through a minefield, got within 10 yards of the closest emplacement, popped up, and fired a rocket into the position, killing two gunners and five riflemen. He reloaded and fired into a second position, killing two more. Then he grabbed hand grenades from his belt and lobbed them into any crevice that fired at him.

As the dust settled, he scrambled to his feet, ran in front of his company’s position, reached another machine gun’s spot, crept within 15 yards, and fired another rocket. He again reloaded and took out a second gun. The next day, the Americans had the advantage, largely in part to Cano’s vigilance. Armed with this trusty rocket launcher, he ran through the killzone and destroyed three more guns and six gunners. In a two-day period, he single-handedly killed more than 30 combatants.

Staff Sergeant Rudolph B. Davila

Rudolph B. Davila left the U.S. Army as a second lieutenant and spent the rest of his working life as a Los Angeles school teacher. In 2000, alongside 21 other Americans who received the Distinguished Service Cross, Davila’s award was upgraded to the MOH 56 years after the fact. Davila served as an officer and was in charge of 130 men who assaulted the Anzio beachhead in 1944. They reached a hilltop where entrenched machine gun nests were waiting to ambush them once they breached their line of sight.

Unwilling to allow his men to get slaughtered and using lessons learned from World War I, Davila ordered his men to retreat. He stayed in the position alone while his men, 50 yards behind, passed him a machine gun, a tripod, and boxes of ammunition. Davila perched his machine gun on his knee and started firing — bullets bounced all around him, even pinging off his tripod. He wiped out one gunner’s position and called a second machine gunner to join him so he could assault forward. But the soldier was shot in the chest as soon as he arrived. Davila dove for cover and used hand signals to direct his platoon where to fire on the enemy. He ran to a tank that was on fire, pulled himself up to the tank’s turret, and unleashed hell on the other three German positions.

Davila then jumped off the tank and sprinted 130 yards to a bombed-out, enemy-occupied farmhouse, ignoring the pain in his wounded leg. Davila reached the attic, rained down hand grenades on five German soldiers, and eliminated them with rifle fire.

Private Joe Gandara

Private Joe Gandara was an Airborne Ranger who hailed from Santa Monica, California, and served with D Company, 2nd Battalion, 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 17th Airborne Division. On June 9, 1944, his platoon was attacked by an overwhelming force of German soldiers in the small French village of Amfreville. This village is known as a place where many Americans endured long hours of questioning after they were captured.

The offensive was suppressed for four hours until Gandara volunteered to advance. Exposed and completely alone, his mission was to mark German targets and launch a surprise counterattack. When he discovered German firing positions, he swung his rifle to his hip and fired as he ran to eliminate three separate hostile encampments. During the onslaught, he was fatally wounded and succumbed to his injuries. In March 2018, his Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the MOH.

Staff Sergeant Macario* Garcia

As a Mexican-born immigrant and rancher, Macario Garcia enlisted in the U.S. Army and stormed the beaches of Normandy with the 4th Infantry Division on D-Day. He spent four months in the hospital for wounds suffered during the invasion. When he recovered, he rejoined his unit as a squad leader and bravely launched a counterassault against German machine gun positions near Grosshau, Germany.

During the fight, he was wounded in the shoulder and foot but refused medical attention. Garcia recognized the situation he was in and volunteered to venture alone through the killzone to surprise the enemy. They were pinned down and enemy fire was relentless — it would not be an easy task. Garcia crawled on his hands and knees, lobbed a grenade on top of the Germans suppressing his teammates, and waited for the explosion. When there was only silence, he crawled to a second machine gun, threw more grenades, and fired with his rifle. In total, Garcia killed six enemy combatants and captured four. Only after he succeeded did he receive medical aid.

* while the spelling of his name varies by document, this is the name that rests on his tombstone

Private First Class Harold Gonsalves

In high school, Harold Gonsalves played many sports and singing in the glee club, but he ultimately dropped out to work. In May 1943, he enlisted in the Marine Corps as a cannoneer. Artillery crews aren’t typically located on the front lines because they provide much-needed support from afar. Gonsalves was an exception — he served amongst infantrymen as a forward observer during the liberation of Guam and the assaults on the Marshall Islands.

The last major assault on Japan occurred during the Battle of Okinawa, and Gonsalves was leading the charge. As he called out positions located on an enormous mountain on the Motobu Peninsula, the officer in charge pushed forward to the frontlines. Gonsalves and another Marine were responsible for laying telephone lines to communicate with headquarters. While other Marines were focused on their tasks, an enemy hand grenade bounced between them. With seconds to respond, Gonsalves hurled his body on top of it as it detonated. He did not survive. His selfless act protected his teammates in the immediate vicinity. If he had not stifled the blast, none of them would have made it out in one piece.

Private First Class David M. Gonzales

Los Angeles-native David Gonzales belonged to the U.S. Army’s Company A, 127th Infantry, 32d Infantry Division. While serving in the Phillippine Islands, he was pinned down and stunned after a 500-pound bomb exploded along their perimeter. The blast buried five soldiers under immovable dirt and debris compacted together. There was no way they’d be able to dig their way out using only their hands. Entombed where no one could hear them scream, the soldiers feared no one would come to help and they would suffocate.

Fortunately, Gonzales witnessed their live burial and crawled 15 yards under a rainstorm of gunfire while carrying an entrenching tool. The commanding officer also joined the effort, but he was struck and killed during the firefight. At first on his hands and knees, Gonzales successfully dug out one soldier, who snuck out of the sand and rocks to find appropriate cover. Gonzales stood up so that he could dig faster, and enemy snipers pinpointed his location. Completely exposed, he extracted two more soldiers before being mortally wounded. Three lives were saved that day because of Gonzales’ quick and selfless actions.

Private First Class Silvestre S. Herrera

Silvestre Santana Herrera was born in Mexico before he immigrated with his parents to El Paso, Texas. His parents died from an influenza outbreak when he was 18 months old, and he went to live with his uncle. When he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1944, he could have opted out because of his Mexican citizenship. However, Herrera chose to serve his new home nation. He deployed to Europe with the Texas Division (Company E, 2d Battalion, 142d Infantry Regiment, 36th Infantry Division) and exemplified heroism in an instant despite being surrounded by death.

While on patrol on a road in Mertzwiller, France, Herrera’s unit was ambushed by a fortified machine gun emplacement. His teammates scrambled for cover while Herrera sprinted alone to attack the enemy position. He killed several Germans and captured eight more. A second machine gun emplacement opened up on his platoon, suppressing their advancement. Again, Herrera set his sights on destroying their will to fight. Between his position and the second gun lay a minefield. Using a wooden two-by-four, he examined the soil in front of him as he slowly advanced. The Germans zeroed in on his position, forcing him to hurry through the minefield or risk being shot. As gunfire drew closer, he moved toward cover but stepped on a landmine, which detonated and blew him into the air. He landed on a second landmine that severed his legs below the knee.

While catastrophically wounded, he rolled onto his stomach and suppressed the enemy position with his rifle. A friendly squad flanked the gun while their attention was on Herrera, and the nest was captured. Despite the pain and blood loss, he was rushed to a hospital and made a full recovery. Herrera is the only individual to receive both the Medal of Honor and the Premier Mérito Militar, Mexico’s highest award for bravery.

Staff Sergeant Salvador J. Lara

SSG Salvador J. Lara led his rifle company of the U.S. Army’s 45th Division into Salerno, Italy, as they broke through the line and chased the retreating German soldiers into the nation’s capital and toward Rome. Lara and his company caused two enemy mortar teams to abandon their positions as they killed three soldiers and captured 15 more. The next morning — on May 28, 1944 — he suffered a severe leg injury that would’ve taken him off the line. He instead requested to destroy an enemy machine gun that had wounded and killed several Americans. He equipped his Browning Assault Rifle (BAR) and aggressively charged into the gun after crawling within yards of it.

Lara neutralized all of the gun crew, opened fire and killed three more from a second gun position, and fired upon two more teams, who fled. For his actions, he received the Distinguished Service Cross, which was upgraded to the Medal of Honor in 2014.

Sergeant Jose M. Lopez

Jose M. Lopez may not have looked like a giant with his 5-foot-5, 130-pound frame, but his determination during the Battle of the Bulge said otherwise. Before he joined the military, Lopez was turning heads as a star boxer after he train-hopped to Atlanta and impressed a boxing promoter. His 52-3 record proved that “Kid Mendoza” could handle his own, and even once met New York Yankees superstar Babe Ruth. After his boxing career ended in 1935, he purchased a false birth certificate so that he could join the Merchant Marines, where he worked until 1941. The following year, he enlisted in the U.S. Army. Lopez was wounded on D-Day plus one (June 7, 1944), but he refused medical attention.

Lopez added a Bronze Star and Purple Heart to his uniform but continued to fight across France and Belgium. On Dec. 17, 1944, his weapons platoon was about to be overrun in the snowy forest near Krinkelt. As German Tiger tanks and infantry soldiers neared his position, Lopez ran with a machine gun to a nearby foxhole and took aim. He immediately killed 10 enemy foot soldiers before the tank fired upon him. After recovering from the concussive blast, he wiped out a flanking platoon of 25 soldiers. Using guerilla tactics to run to cover, shoot effectively and precisely, and then move onto the next position, Lopez successfully killed more than 100 enemy soldiers during seven hours of nonstop combat.

In 2001, Lopez, who retired from the Army as a master sergeant, told the San Antonio Express-News, “You learn to protect the line and do the best you can with the ammunition you have, and I did it.”

Private Joe P. Martinez

Joe P. Martinez is one of 16 recipients to be awarded the Medal of Honor during World War II for their actions while on American soil. On June 7, 1942, the Japanese military invaded two islands located on the Aleutian chain of Alaska: Kiska and Attu. The capture of these islands were a strategic footprint that the Japanese highly valued in order to launch strike missions on the U.S. mainland. The U.S. Army 7th Division was sent to destroy them. Through mountainous terrain, snowy hilltops, and entrenched and elevated enemy positions, Martinez and his men had a handful to deal with. The enemy located between East Arm Holtz Bay and Chichagof Harbor repeatedly countered Allied attacks, and the American effort was at a standstill.

Despite being reinforced with a battalion of soldiers, their movement was limited due to machine gun fire, mortars, hand grenades, and rifle fire. Martinez moved forward with his BAR, encouraged his men to make the difficult climb, and engaged with the determined enemy. Part of his MOH citation reads: “This success only partially completed the action. The main Holtz-Chichagof Pass rose about 150 feet higher, flanked by steep rocky ridges and reached by a snow-filled defile. Passage was barred by enemy fire from either flank and from tiers of snow trenches in front. Despite these obstacles, and knowing of their existence, Pvt. Martinez again led the troops on and up, personally silencing several trenches with BAR fire and ultimately reaching the pass itself. Here, just below the knifelike rim of the pass, Pvt. Martinez encountered a final enemy-occupied trench and as he was engaged in firing into it he was mortally wounded. The pass, however, was taken, and its capture was an important preliminary to the end of organized hostile resistance on the island.”

Private First Class Manuel Pérez Jr.

Manuel Pérez Jr. was born in Oklahoma before he and his family moved to Chicago. He served with Company A, 1st Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 11th Airborne Division as a private first class. He fought valiantly against the Japanese in Luzon, Philippines, to recapture Fort William McKinley on Feb. 13, 1945. Pérez used hand grenades to explode 11 of 12 heavily supported pillboxes and his rifle to dispatch enemies in the open.

The final pillbox rattled .50-caliber twin machine guns upon his position. Perez flanked it from the side, running while shooting at four Japanese fighters as he advanced. When he was within 20 yards of their position, he pulled out a grenade and hurled it into the pillbox, but the occupants ran into a tunnel at the rear of the bunker. He shot and killed four soldiers, reloaded his rifle, then killed four more. Another Japanese soldier charged at him with a fixed bayonet, and Perez was hit to the ground. He lost his rifle but managed to steal his enemy’s, ultimately killing the Japanese fighter with his own weapon.

He continued to engage, running into the pillbox and using the butt of his rifle to pulverize three more combatants until they were neutralized. He bayoneted the lone surviving soldier. In the end, he single-handedly killed 18 enemy troops and wiped out 12 pill boxes, which freed his team to advance.

Sergeant Manuel V. Mendoza

Sergeant Manuel V. Mendoza — nicknamed “The Arizona Kid” for his combat heroism — was a jack of all trades. On Oct. 4, 1944, on Mount Battaglia, Italy, Mendoza was serving as a platoon sergeant with Company B, 350th Infantry, 88th Infantry Division. He braved a fierce German counterattack despite already being wounded in the leg and arm. Mendoza and his platoon kept their heads down as a barrage of mortar fire formed craters around them. Knowing the enemy used mortars to advance, he grabbed his Thompson sub-machine gun and ran to a hill crest where he witnessed 200 Germans hustling up the slopes of his position carrying flamethrowers, machine guns, rifles, and hand grenades.

He fired down on top of them with five magazines of ammo, killing 10 soldiers. He picked up a nearby carbine rifle and continued his lone defense. A German soldier manning a flamethrower was almost to the top, but Mendoza dispatched him with his pistol. He jumped back into an abandoned machine gun nest and continued to fire, but the overwhelming force was nearing his position. Mendoza was being flanked from all sides, so he picked up another machine gun, held it at his hip, and fired at the Germans until his weapon jammed. He reached for the hand grenades in his belt and began pulling the pins to throw. Once they exploded, he slid down the hill, captured a wounded soldier, and continued his fight until friendlies arrived to back him up.

Mendoza single-handedly defended a position, captured one enemy soldier, and killed approximately 30 more. Following the war, he was promoted to master sergeant and served during the Korean War, where he was wounded. Mendoza was honorably discharged in 1953.

Private Cleto L. Rodríguez

Cleto L. Rodríguez lost both his parents when he was 9 years old and was raised by relatives in San Antonio, Texas. Rodríguez joined the Army in 1944. He deployed to the Philippines with 148th Infantry, where he and another soldier were responsible for overtaking Paco railroad station, which was heavily defended by Japanese fighters, during the Battle of Manila. As an automatic rifleman, his job was to suppress the enemy and lead assaults.

While his platoon was crossing an open field only 100 yards from the railroad station, they were forced to stop while under attack by precise fire. Alongside another soldier, Rodríguez moved 60 yards from the objective to a house in view of the Japanese. The two-man assault element accurately coordinated fire, eliminating 35 Japanese infantry. The enemy advanced to open pillboxes, but Rodríguez and his teammate killed 40 more soldiers, halting and confusing the enemy’s strategy. As all Japanese weapons were focused on the house, they moved to within 20 yards of the station. His companion covered Rodríguez as he stood next to the doorway of the station.

Rodríguez pulled the pins on five hand grenades and tossed them into the station, which killed seven and destroyed a 20mm gun and heavy machine guns. As their ammo depleted, they leapfrogged back to their platoon, but his teammate was struck and killed. The pair killed 82 enemy soldiers in two and a half hours of fighting. Two days later, Private Rodríguez eliminated six Japanese soldiers and took out another 20mm gun.

Private First Class Alejandro R. Ruiz

Alejandro R. Ruiz was born to Mexican immigrants in Loving, New Mexico, where he would start his career in the U.S. Army. Ruiz, who also served in the Korean War, retired as a master sergeant in the 1960s. While serving in the Pacific during World War II, his platoon was responsible for ousting the last of the Japanese troops hiding out near the ridges near the village of Gisumuka. On April 28, 1945, every person in his platoon except for himself and a squad leader were either killed or wounded in an ambush.

During the ambush, Ruiz equipped his BAR and approached a bunker located 35 yards away. He climbed on top of the bunker alone and pulled the trigger. His weapon jammed, and a Japanese fighter charged him. Ruiz swung his rifle around and bludgeoned his attacker to death. He then sprinted back to his platoon while bullets skipped around his feet and got a second firearm. He returned to the bunker with a fresh gunshot wound to his leg and bounced between pillboxes killing the enemy. He effectively silenced the machine gun nest and single-handedly killed a total of 12 Japanese soldiers.

Private First Class Jose F. Valdez

Jose F. Valdez served in the U.S. Army, Company B, 7th Infantry Regiment, 3d Infantry Division, where his unit was responsible for attacking German positions located along the Siegfried Line. This area was a 392-mile concrete defense fortification with over 18,000 bunkers, tank traps, and tunnels sprinkled between. On Jan. 25, 1945, while at an outpost about 500 yards beyond American lines, Valdez and five others were ambushed by German armor and infantry units near Rosenkrantz, France. Valdez spotted an approaching German Tiger tank and engaged it — and the enemy soldiers around it — with his assault rifle.

Two full companies of Germans entered the fight, and Valdez killed three Germans while three of his teammates were wounded. A bullet passed through his back, but he continued to fight until he reached a field artillery telephone and called for a barrage within 50 yards of his position. After shooting at the 200 raiding soldiers with the remainder of his ammo, Valdez pulled himself back behind the safety of American lines, where he succumbed to his wounds.

Staff Sergeant Ysmael R. Villegas

Ysmael R. Villegas grew up in a Latino community in Riverside, California, the oldest of 13 children. He was given the nickname Smiley because of his cheerful disposition and kind heart. When the Army came calling in 1944, he didn’t want to go. He once wrote home, “I got the Purple Heart for just a little scratch on my ear, but don’t tell my mom because she would get worried.”

The day before his 21st birthday, Villegas was killed along the Villa Verde Trail in Luzon, Philippines, while assaulting a heavily fortified Japanese position. As hand grenades and demolition charges exploded near his position, he stood up and charged through a hail of automatic machine gun fire into enemy caves and foxholes. His men from the 32nd Infantry Division saw their squad leader fighting alone, which inspired them to join the effort. Each enemy foxhole contained a determined Japanese rifleman firing back at Villegas, but he cleared five foxholes before he was struck and killed while attacking the sixth. Villegas was posthumously awarded the MOH for his role during the operation.

Korean War

Corporal Joe R. Baldonado

Colorado-native Joe R. Baldonado was a machine gunner with the 187th Airborne Infantry Regiment during the Korean War. On the morning of Nov. 25, 1950, the enemy in Kangdong exposed their unit when they were desperate for a resupply of ammunition. They closed within 25 yards in an attempt to overrun their position. CPL Baldonado placed his machine gun within the view of the ambushing enemy to allow his team to desperately recover to join in the surprise fight for their lives.

According to Baldonado’s MOH citation: “Several times, grenades exploded extremely close to Corporal Baldonado but failed to interrupt his continuous firing. The hostile troops made repeated attempts to storm his position and were driven back each time with appalling casualties. The enemy finally withdrew after making a final assault on Corporal Baldonado’s position during which a grenade landed near his gun, killing him instantly.” He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Corporal Victor H. Espinoza

Victor H. Espinoza lived in El Paso, Texas, both before the Korean War and up until his death in 1986. Corporal Espinoza and A Company, 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment had the task to recapture “Old Baldy,” a strategic hill near Chorwong comprised of 12 Chinese outposts. It was often called “Suicide Hill” because of the daunting task to capture it. After witnessing his squad leader go down and the rest of his company pinned down by overwhelming rifle fire, mortars, and artillery, Espinoza charged the enemy carrying only the rifle he had in his hands and the grenades in his pockets.

After silencing a machine gun and its crew, Espinoza’s citation reads, and “continuing up the fire-swept slope, he neutralized a mortar, wiped out two bunkers, and killed its defenders. After expending his ammunition, he employed enemy grenades, hurling them into the hostile trenches and inflicting additional casualties. Observing a tunnel on the crest of the hill, which could not be destroyed by grenades, he obtained explosives [TNT], entered the tunnel, set the charge, and destroyed the tunnel and the troops it sheltered.”

Espinoza was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, which was later upgraded to the MOH. He retired from the Army as a master sergeant in 1952.

Private First Class Fernando Luis García

Fernando Luis Garcia worked as a file clerk in Puerto Rico before he joined 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division in support of the Korean War. Located at an outpost a mile forward of the main line, Garcia selflessly sacrificed his life for his fellow Marines. When the enemy launched a pre-dawn raid, they violently crushed their positions with artillery, hand grenades, and mortar fire. Garcia volunteered to go to the supply point to retrieve more hand grenades to repel the assault despite being targeted by the enemy.

While gathering more supplies, he heard the thump of a hand grenade land at the feet of the acting platoon sergeant. Garcia shouted, “I’ll get it!” and hurled his body on top of the grenade to absorb the explosion. He was killed instantly, and his fellow Marine survived. Garcia’s body was never recovered — by the time the sergeant came-to following the blast, the enemy had overrun the position.

Private First Class Edward Gómez

At 17 years old, Edward Gómez enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps and served with 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Division during the Battle of the Punch Bowl, named so because of the mountains surrounding it on three sides. While serving as an ammunition bearer on Sept. 14, 1951, his unit attacked a heavily fortified position along Hill 749. When his squad moved to eliminate a prepared enemy counterattack, he volunteered to leave his trench in search of a gun. When a hand grenade landed between the weapon and himself, Gómez shouted a warning before picking up the grenade with his bare hands. He dove into a ditch as his teammates watched in horror as it exploded into his body.

He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for sacrificing himself to save his fellow Marines.

Sergeant Eduardo C. Gomez

Sergeant Eduardo C. Gomez served with the U.S. Army’s 1st Cavalry Division in Tabudong, Korea. While on patrol on the afternoon of Sept. 3, 1950, Gomez’s command post became immobilized by unrelenting rocket fire and machine guns. The enemy closed with 75 yards and continued to push closer with the support of a tank. Gomez realized that they were at a tactical disadvantage and willingly exposed himself. He crawled 30 yards on his stomach into the killzone of a rice field to personally dispatch the tank.

Gomez boarded the tank, pried open the hatch, pulled the pin on a hand grenade, tossed it into the hull, and hopped off as it exploded. As he returned to his position, he was wounded on his left side but refused to be medically evacuated. He noticed that the tripod to a .30-caliber machine gun had been rendered useless by enemy fire and grabbed the blistering hot weapon in his bare hands. When he was ordered to retreat as the threat of an assaulting force became overwhelming, he continued to accurately suppress the enemy and inflict heavy casualties. Gomez survived the war, but died in 1976, before his MOH was awarded. Gomez’s nephew accepted the medal on his behalf in 2014.

Staff Sergeant Ambrosio Guillen

Ambrosio Guillen hailed from El Paso, Texas, and served in the Korean War with 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Division (reinforced), where he led his platoon over unfamiliar terrain to set up defensive firing positions near Songuch-on. The Chinese used nightfall to cover their infiltration to attack their outpost with two battalion-sized elements. When the gunfire started, mortars, artillery, and rockets supported their advance. The fighting got close enough that members of his platoon engaged in hand-to-hand combat.

Although seriously wounded during the onslaught, Guillen refused to be evacuated and continued ordering and inspiring his men through unmatched combat leadership. Ultimately, he succumbed to his wounds and was declared killed in action (KIA). His fierce determination to lead until the end allowed for his teammates to hold the defense for two days before the cease fire.

Corporal Rodolfo P. Hernandez

Rodolfo “Rudy” P. Hernandez served with the U.S. Army’s 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team near Wonton-ni and single-handedly conducted a bayonet charge on the enemy. The 20-year-old paratrooper was severely wounded by a volley of enemy hand grenades. His platoon lost communications with him and retreated for cover during the chaos, which included mortars, artillery, and explosions during the 2 AM assault on May 31, 1951. While rain filled his foxhole with mud, Hernandez continued to fire on the North Korean troops, despite having shrapnel in every body part.

Eventually, his rifle was rendered useless. Although bloody and dizzy from his wounds, he fixed his bayonet, threw six hand grenades, and yelled, “Here I come!” as he charged the enemy. Hernandez bayoneted six soldiers to death, which allowed his platoon to regroup for the counterattack. After the melee, he dropped to the ground — unconscious but alive. He became one of only three paratroopers to receive the Medal of Honor. A month after the battle, he regained consciousness from his coma and recovered from his injuries. Hernandez died in 2013 at age 82.

First Lieutenant Baldomero López

First Lieutenant Baldomero “Baldy” López was photographed leading a Marine assault from a landing craft into Inchon, South Korea, on Sept. 15, 1950, during Operation Chromite. As they breached the shore of Red Beach, all hell broke loose as enemy machine guns ripped through their elements. Baldy’s platoon was pinned down behind a seawall by a North Korean machine gun position. As he inspired his men throughout his career as a Marine officer from the U.S. Naval Academy to Quantico to combat, his men looked to him for guidance.

Baldy grabbed his hand grenade, pulled the pin, and sprinted out from behind cover and into the dragon’s teeth of the machine gun. Three Marines followed closely behind, but Baldy was hit by a strafing burst in the chest and shoulder. His grenade fell onto the ground and to his side. He had a split-second decision to make: roll away, possibly be peppered by shrapnel, and wait seconds for the screams of his Marines, or to smother it with his body. He chose the latter and was killed instantly.

His final letter back home to his family in Tampa, Florida, read as a ballad of a hero: “My business is out here in the Far East where the present international crisis is located. Knowing that the profession of arms calls for many hardships and many risks, I feel that you all are now prepared for any eventuality. If you catch yourself starting to worry, just remember that no one forced me to accept my commission in the Marine Corps.”

Corporal Benito Martinez

Benito Martinez enlisted from the Lone Star state that so many other Hispanic servicemen helmed from and joined the U.S. Army’s 25 Infantry Division as a Light Weapons soldier. Near Satae-ri, Korea, Sept. 6, 1952, Martinez’s position was ambushed as the enemy infiltrated their defensive perimeter. When he recognized that the enemy was preparing to surround them, he elected to stay at his position and fight — alone.

Martinez sprayed and accurately inflicted numerous enemy casualties. His command made several attempts to contact him by a sound power phone, but he refused the order to send a rescue element. For six hours straight, Martinez engaged and fought until his final bullet. He called one last time and told his teammates that the enemy was converging on his position. He was later determined KIA. He received the MOH for single-handedly repelling the opposition.

Sergeant Juan E. Negrón

Juan E. Negrón was originally awarded the Distinguished Service Cross before it was upgraded to the MOH by Congress in 2002. On April 28, 1951, near Kalma-Eri, Korea, Negrón distinguished himself amongst the U.S. Army’s all-Puerto Rican 65th Infantry Regiment. Nicknamed “The Borinqueneers,” the unit saw extensive combat, and Negrón would confront it head-on. The enemy had already broken through their line, and he set up a defensive position located on the right flank. His teammates notified him that they were leaving, but he refused to move from his exposed position to cover their withdrawal.

The enemy passed a road block and were suppressed by his accurate fire. Some got close enough that he could hear them speak — and he answered with a volley of hand grenades. As the sun went down and the moon shone bright, the enemy launched a counterattack. When his unit came to reinforce his position the following morning, the remains of 15 enemy lay nearby. Following his valorous actions, he continued to serve in the Army, reaching the rank of master sergeant. He helped redefine the Army’s combat strategy and even did a stint as the Inspector General in Thailand before retiring after 23 years of service.

Private First Class Eugene Arnold Obregon

Eugene Arnold Obregon, a Los Angeles native, enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps when he was 17 years old. He was assigned to 3rd Battalion, 1st Marine Division (reinforced). In August 1950, he participated in the Inchon Landing, but his heroism took place in the capital city of Seoul. He served as an ammunition bearer to a machine gun squad. They were pinned down by unrelenting machine gun fire. He witnessed a fellow Marine, 19-year-old Bert M. Johnson, collapse after being wounded by the enemy. Armed with only a pistol, Obregon sprinted to his fellow Marine as he fired on the run.

Despite being in the killzone, he dragged Johnson with one hand and continued to fire his pistol with the other. They reached a road, but a platoon-sized element flanked their position. He grabbed Johnson’s carbine, rested his body on top of him to shield him from the danger, and fought valiantly until he was struck and killed by machine gun fire. For his actions in saving a fellow Marine, who made a full recovery, he earned the Medal of Honor.

Master Sergeant Miguel “Mike” Castaneda Peña Jr.

Mike Peña’s family roots were in Mexico before they immigrated to Texas where he enlisted in the U.S. Army when he was only 15 years old. Since the age gap to enter the military was not met, he lied about his age and convinced his recruiters it was fact. In 1941, he participated in Louisiana Maneuvers (a military exercise), trained as a light machine gunner, and even served with the Border Patrol at Sierra Blanca (White Mountain) in Hudspeth County, Texas. During World War II, Peña served with 1st Cavalry Division where he survived 79 days of consecutive combat, including shrapnel wounds to his face and thigh on two separate occasions from a Japanese grenade.

Following World War II, Peña married his wife and earned the rank of master sergeant. When the Korean War was sprouting, he enlisted for six more years to ensure he would see action. While deployed near the Waegwan region, an ambush by the enemy caused confusion among Peña’s platoon. “Master Sergeant Pena rapidly reorganized his men and led them in a counterattack which succeeded in regaining the positions they had just lost,” his citation reads. “He and his men quickly established a defensive perimeter and laid down devastating fire, but enemy troops continued to hurl themselves at the defenses in overwhelming numbers. Realizing that their scarce supply of ammunition would soon make their positions untenable, Master Sergeant Pena ordered his men to fall back and manned a machine gun to cover their withdrawal. He single-handedly held back the enemy until the early hours of the following morning when his position was overrun and he was killed.”

Private Demensio Rivera

Demensio Rivera was born in Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico, and enlisted in the U.S. Army’s 3rd Infantry Division in 1950. The next year, while serving near Changyong-ni, Korea, on May 22 to 23, Rivera distinguished himself in the face of the enemy. At night, a dense fog provided cover to a raiding force, who emerged and assaulted with an overwhelming attack. Rivera immediately engaged targets with his rifle until it jammed. He dropped his weapon and retrieved his pistol and hand grenades. The fighting got so close that Rivera engaged an enemy soldier in hand-to-hand combat.

He expended all of his ammunition and was determined to make his final stand. Armed with a lone hand grenade, Rivera pulled the pin, and waited for the enemy to leap into his bunker. When they emerged, he initiated the grenade, knowing it would be his final contribution to the world. When his teammates discovered the aftermath, they found a severely wounded Rivera and four dead enemy combatants surrounding him. Rivera survived the war and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Upon Congressional review in 2002, it was upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

Private First Class Joseph C. Rodriguez

Six months after Joseph C. Rodriguez graduated college he was sent to Korea to fight with the U.S. Army’s Company F, 2nd Battalion, 17th Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division. On May 21, 1951, Rodriquez led his squad into position to attack a hill near the village of Munye-Ri. Other units made three previous attempts, suffering numerous casualties, and all had failed to overtake the hill. “I was very angry, the fact that they had all of our men pinned down. And I felt something had to be done,” Rodriguez said in an interview with the Library of Congress. “I didn’t even think about it. I just did it.”

The nonchalant reference to his own actions doesn’t mention how he ran up the hill, threw two hand grenades into two machine gun foxholes, then returned to his men to repeat his action again. The second time, he eliminated three entrenched foxholes. For these actions, he was awarded the Medal of Honor. He spent the next 30 years with the Army Corps of Engineers, deploying during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, as well as to several Latin American countries, before retiring in 1980 as a colonel.

Private Miguel A. Vera

Miguel Armando “Nando” Vera was finally laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery in 2014, a welcome homecoming since he was KIA 62 years prior in Korea. Vera joined the U.S. Army’s Company F, 38th Infantry Regiment, 2d Infantry Division at 17 years old and deployed to Chorwon, Korea. He fought heroically during the Battle of Old Baldy. A previous battle forced him to receive care in a field hospital, but he volunteered as an automatic rifleman to leave the aid station and participate in the assault with his unit.

His MOH citation reads, in part, “When the assaulting elements had moved within twenty yards of the enemy positions, they were suddenly trapped by a heavy volume of mortar, artillery and small-arms fire. The company prepared to make a limited withdrawal, but Private Vera volunteered to remain behind to provide covering fire. As his companions moved to safety, Private Vera remained steadfast in his position, directing accurate fire against the hostile positions despite the intense volume of fire which the enemy was concentrating upon him. Later in the morning, when the friendly force returned, they discovered Private Vera in the same position, facing the enemy.”

Vietnam War

Specialist Leonard L. Alvarado

Specialist Four Leonard L. Alvarado enlisted in the U.S. Army’s 1st Cavalry Division in 1968; the next year, he saw action in Phuoc Long Province, Republic of Vietnam, as a member of a quick reaction force. Alvarado’s sister platoon was under fire in the thick, dense jungle and needed immediate support. When they arrived, they too were pinned down by machine gun fire and their path to escape was sealed off. An enemy grenadier wounded and dazed Alvarado with his explosives, but upon recovery, Alvarado immediately neutralized the enemy. He continued through hostile fire to retrieve trapped teammates and push them back to their hastily formed perimeter.

He continued to push forward, his MOH citation reads: “Though repeatedly thrown to the ground by exploding satchel charges, he continued advancing and firing, silencing several emplacements, including one enemy machine gun position. From his dangerous forward position, he persistently laid suppressive fire on the hostile forces, and after the enemy troops had broken contact, his comrades discovered that he had succumbed to his wounds.”

Staff Sergeant Roy P. Benavidez

Roy P. Benavidez was a part of the first wave in Vietnam where he worked as a military advisor assisting the Republic of Vietnam soldiers in training. During a patrol, he stepped on a landmine and woke up in a Texas hospital, evacuated from the warzone with no memory of the event. Following his unexpected recovery, Benavidez volunteered to return to Vietnam, but this time with an Army Special Forces detachment. He arrived in Lộc Ninh province on his second tour and adopted the call sign Tango Mike Mike, or That Mean Mexican, which his teammates affectionately called him.

On May 2, 1968, a distress call from a 12-man Special Forces patrol comprised of three Green Berets and nine Montagnard Tribesmen, alerted that over 1,000 North Vietnamese surrounded their position. Benavidez ran to the helipad to see MEDEVAC helicopters shot to pieces trying to rescue them. Armed with only a knife and medical bag, he boarded another helicopter and scorched through the sky to save his teammates. When he reached their position, every soldier had been wounded. He jumped off the skids of the helicopter and provided immediate first-aid. The helicopter’s pilot had been shot, but he continued to drag his wounded teammates to the bird.

Benavidez was shot through the back, and a blast from a hand grenade peppered him with shrapnel and knocked him out. When he awoke, the helicopter was on fire. An enemy soldier slashed him in the arm with a bayonet and hit him in the jaw with his rifle. Benadivez killed the soldier with his knife. Another helicopter came to rescue them but was also shot down.

In the six-hour firefight from hell, Benavidez was shot seven times, had 28 fragmentation holes in his body, and rescued eight lives. When he passed out from the pain and exhaustion, doctors thought he had died. He awoke in a body bag and used his spit to alert to them he was still alive, despite his catastrophic injuries. He retired as a master sergeant and died in 1998.

Staff Sergeant Felix M. Conde-Falcon

Felix Modesto Conde-Falcon was born in Juncos, Puerto Rico, and raised in Chicago. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1963 and was assigned to the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division in South Vietnam. His son said he would hear stories about his father, but it took him 20 years to track down his “brothers” to learn about his heroism. On April 4, 1969, Sergeant Conde-Falcon and his platoon discovered a bunker complex hidden deep in a wooded area. They estimated it was a battalion command post. Conde-Falcon’s fire team was selected to eliminate it.

His MOH citation reads, “Moving out ahead of his platoon, Staff Sergeant Conde-Falcon charged the first bunker, heaving grenades as he went. As the hostile fire increased, he crawled to the blind side of an entrenchment position, jumped to the roof, and tossed a grenade into the bunker aperture. Without hesitating, he proceeded to two additional bunkers, both of which he destroyed in the same manner as the first. Rejoining his platoon, Staff Sergeant Conde-Falcon advanced about one hundred meters through the trees before coming under intense hostile fire. Selecting three men to accompany him, he maneuvered toward the enemy’s flank position. Carrying a machine gun, he single-handedly assaulted the nearest fortification, killing the enemy inside before running out of ammunition. After returning to the three men with his empty weapon and taking up an M-16 rifle, he concentrated on the next bunker. Within ten meters of his goal, Staff Sergeant Conde-Falcon was shot by an unseen assailant and soon died of his wounds.”

Lance Corporal Emilio A. De La Garza

Emilio De La Garza was a 1968 graduate of E.C. Washington High School, located in East Chicago, Indiana. He soon got married, had a child, and joined the U.S. Marines. He and his wife, Rosemary, enjoyed a trip to Hawaii, where the high school sweethearts celebrated their honeymoon. Two days later, De La Garza returned to Vietnam, where he selflessly sacrificed his life to protect his platoon. He served as a machine gunner with 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division. While he and his platoon were returning from a nighttime operation near DaNang, his squad observed two fleeing Viet Cong soldiers.

The enemy ran to a small pond and hid in the reeds and bush. De La Garza, alongside his platoon commander and another Marine, pursued to capture them. One enemy soldier resisted and during the melee pulled a pin to a hand grenade. De La Garza yelled to warn his teammates, then put his body between them and the danger. He was killed in action and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Private First Class Ralph E. Dias

Private First Class Ralph Dias was born in Indiana, Pennsylvania. In 1967, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps and joined 3rd Platoon, D Company, 7th Battalion, 1st Marine Division in Vietnam in April 1969. Dias and his M-60 weapons squad arrived to a chaotic scene where two units were in contact with the enemy and suffered heavy casualties. He initiated a charge across the killzone to silence the source of enemy fire.

His MOH citation reads: “Severely wounded by enemy snipers while charging across the open area, he pulled himself to the shelter of a nearby rock. Braving enemy fire for a second time, PFC Dias was again wounded. Unable to walk, he crawled 15 meters to the protection of a rock located near his objective and, repeatedly exposing himself to intense hostile fire, unsuccessfully threw several hand grenades at the machine gun emplacement. Still determined to destroy the emplacement, PFC Dias again moved into the open and was wounded a third time by sniper fire. As he threw a last grenade which destroyed the enemy position, he was mortally wounded by another enemy round.”

Specialist Jesus S. Duran

Jesus Duran was born in Juarez, Mexico, the middle child of twelve siblings, before he enlisted in the U.S. Army at 20 years old and deployed with the 1st Cavalry Division to Vietnam. During a search-and-destroy operation on April 10, 1969, his reconnaissance platoon moved into an elaborate bunker complex, and gunfire erupted from all sides. The command post was in danger of being overrun by the enemy. The gunfire and violence was coordinated enough to accurately fire on Duran’s troops. Dust kicked up around his legs, bullets snapped past his head, and shrapnel from exploding grenades impacted everything that moved.

As a machine gunner carrying the M-60, Duran equipped it and ran, firing at the hip, to suppress the enemy. Two of his teammates were wounded; to neutralize the positions trying to kill them, Duran mounted a log and aimed down on top of the enemy foxholes. He killed four and disorganized the enemy’s planned defense. He was later promoted to sergeant. Following the war, Duran continued service as a corrections officer in San Bernardino, California, where he focused on rehabilitating youth on educational trips. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 2014.

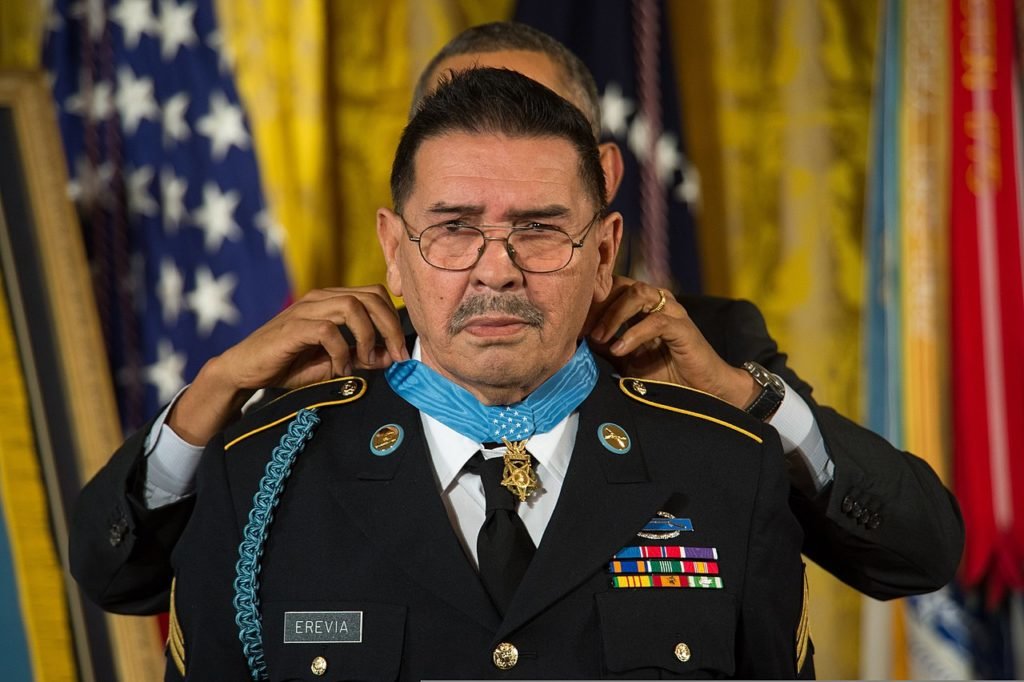

Specialist Santiago J. Erevia

Santiago Erevia, a 23-year-old radio-telephone operator, single-handedly changed the course of events that occurred May 21, 1969, with the 101st Airborne Division near a small town called Tam Ky, along the South China Sea. The North Vietnamese were infamous for their bunkers, hideaways, and tunnels. As Erevia’s company entered a rice paddy, 200 yards of open land stood before them. When they reached the open, spider holes and camouflaged soldiers erupted with sniper fire, RPGs, and AK47s. Those who were not struck by gunfire moved to cover; Erevia dove to the ground and crawled to his wounded teammates. He issued first-aid and gathered ammunition for the battle.

The enemy closed to within 5 to 10 feet. Erevia destroyed four enemy bunkers — the first three with hand grenades, the last with his rifle. “I zigzagged, firing my M-16,” he told NPR in 2014. “One of the NVA soldiers stood up — I was about maybe two or three feet away from him. I shot him point-blank with my M-16. End of story.” After the war ended, Erevia served 17 years with the Texas National Guard, ending his military career as a sergeant. For his valorous actions, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, which was upgraded to the Medal of Honor in 2014. He died in 2016 at the age of 70.

Specialist Daniel Fernandez

Daniel Fernandez had dreams of owning his own ranch and living a quiet life. But he never made it home from Vietnam alive. Serving with the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry Division, Fernandez braved enemy fire in Cu Chi, Hau Nghi Province, Vietnam, on Feb. 18, 1966. Fernadez and two others volunteered to retrieve a fellow soldier who was wounded and alone during a Viet Cong ambush.

When they reached the wounded soldier, one of the volunteers was struck in the knee by rifle fire. As the gunfire intensified, the group moved to cover, when an enemy hand grenade fell into the group’s circle. Fernandez saw it and knew he had seconds to make a decision. He threw his body over the grenade. It detonated, killing him instantly and saving the lives of four fellow soldiers.

Sergeant Candelario Garcia

Candelario Garcia hailed from Corsicana, Texas, joined the U.S. Army in 1963, and would become a team leader who conducted reconnaissance operations near Lai Khê, near Highway 13 northwest of Saigon. While leading his team from 1st Battalion, 2nd Infantry, 1st Brigade,1st Infantry Division, Sergeant Garcia discovered a communications wire that led to an enemy stronghold in a dense wooded area. His team was immediately engaged by the fortified enemy, who shot and dropped them in the open.

Garcia sprung toward the sound of gunfire instead of seeking cover, knowing that winning the gunfight was more important at that time than anything else. His citation reads, “Sergeant Garcia crawled to within ten meters of a machine gun bunker, leaped to his feet and ran directly at the fortification, firing his rifle as he charged. Sergeant Garcia jammed two hand grenades into the gun port and then placed the muzzle of his weapon inside, killing all four occupants. Continuing to expose himself to intense enemy fire, Sergeant Garcia raced fifteen meters to another bunker and killed its three defenders with hand grenades and rifle fire. After again braving the enemies’ barrage in order to rescue two casualties, he joined his company in an assault which overran the remaining enemy positions.”

Garcia was also awarded the Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, Air Medal, Army Commendation Medal with “V” Device and one bronze oak leaf cluster, among other awards.

Sergeant Alfredo Cantu Gonzalez

Alfredo “Freddy” Cantu Gonzalez picked cotton as a boy in Texas and played high school football. During his first tour with the 1st Marine Division to Vietnam, he felt a kinship with the Vietnamese people he saw working in the fields. He told his friends that he wouldn’t return to Vietnam and instead taught guerilla warfare to Marines preparing to deploy. After he learned an entire platoon had been wiped out — including some Marines who he had previously served with — he deployed a second time and participated in the initial phase of Operation Hue City.

On Jan. 1, 1968, Gonzalez supported a convoy near the village of Lang Van Long when it was attacked. He directed fire to eliminate enemy snipers, and the convoy continued before being attacked a second time. A Marine had been struck and fell off a tank. Gonzalez ran to his rescue and was struck by fragmentation grenades; however, he still managed to lead an assault to destroy a machine gun emplacement up the road with grenades of his own. The convoy moved to Hue, and although Gonzalez was seriously wounded during the fight, he refused medical attention.

The next day, he fought valiantly while pinned down by a numerically superior enemy: “Gonzalez used several antitank weapons against heavily fortified enemy positions while exposed to enemy fire. He held back the enemy advance and destroyed an enemy rocket position before he was mortally wounded. Gonzalez was hit by the last rocket fired by the enemy, and died in the Saint Joan of Arc Catholic Church, where he had taken cover. For his actions between January 31 and February 4, 1968, Gonzalez was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.”

Lance Corporal Jose Francisco Jimenez

Jose Francisco Jimenez was born in Mexico City, Mexico before he moved to Arizona for high school. Although he wasn’t a U.S. citizen, he earned his right to don the uniform of the U.S. Marine Corps. Jimenez, who had several friends drafted into service, believed it was his duty to enlist. In Vietnam, he served as a fire team leader with Company K, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division, in operations against the enemy on Aug. 28, 1969. The Vietnamese Army had camouflaged positions and superior firepower; Jimenez personally led an assault on their positions.

A passage from his MOH citation reads: “He personally destroyed several enemy personnel and silenced an anti-aircraft weapon. Shouting encouragement to his companions, Lance Corporal Jimenez continued his aggressive forward movement. He slowly maneuvered to within ten feet of hostile soldiers who were firing automatic weapons from a trench and, in the face of vicious enemy fire, destroyed the position. Although he was by now the target of concentrated fire from hostile gunners intent upon halting his assault, Lance Corporal Jimenez continued to press forward. As he moved to attack another enemy soldier, he was mortally wounded.”

Lance Corporal Miguel Keith

In 2017, Richard V. Spencer, the Secretary of the U.S. Navy, renamed the fifth Expeditionary Sea Base (ESB) the Miguel Keith (T-ESB-5) after the U.S. Marine and San Antonio, Texas, native. Lance Corporal Keith deployed to Quang Ngai, Vietnam, with Combined Action Platoon 1-3-2, 3rd Marine Amphibious Force. On the morning of May 8, 1970, a numerically superior force converged onto their position, and he was wounded during the ensuing firefight. The chaos caused confusion amongst the platoon, and Keith ran across open terrain to check on their defensive positions while carrying his automatic machine gun.

Five enemy combatants came into view as they creeped closer to the command post. Although Keith was completely exposed, he fired and killed three raiders and dispersed the remaining two. A grenade fell at his feet and exploded, worsening his wounds. As he lay bloodied on the ground, a 25-enemy element was mobilizing to attack their position. Keith picked up his weapon and killed four attacking enemies while charging their position. The rest fled behind cover and fired upon him from there until he was mortally wounded.

Private Carlos Lozada

Lozada Playground sits on the north side of East 135th Street between Alexander and Willis Avenues in Bronx, New York. Sometimes we unassumingly walk past schools, statues, or playgrounds without much thought as to who it is named after. The playground was first created in 1938; when major finishes and improvements were made in 1995, it adopted the name of Medal of Honor recipient Private Carlos Lozada. Lozada was posthumously awarded the medal after serving with the U.S. Army’s 173d Airborne Brigade on Hill 875 in the Dak To region, 3 miles from the Cambodian border. His role was to alert his teammates, located 35 yards behind his sentry outpost, if he saw any enemy footprints.

A company from the North Vietnamese Army sneaked to within 10 yards before Lozada could call his teammates for help. He immediately fired his heavy machine gun to disperse the enemy, killing 20 combatants. The enemy fire continued, and his teammates pleaded for him to withdraw. The enemy began to outmaneuver them and tried to cut off their retreat along their west flank. Lozada realized that if he stopped firing, his men would be surrounded and unable to defend themselves, so he stayed and covered them. He was mortally wounded protecting others instead of himself.

Specialist Alfred V. Rascon

Alfred Rascon was born in Chihuahua, Mexico, before his family immigrated to California when he was 2 or 3 years old. As he grew, he would talk to veterans from the Korean War near La Colonia and rummage through old World War II memorabilia in a local store. He was enamored with the military and even routinely read Sgt. Rock comics. The influence was enough for him to enlist in the U.S. Army at age 17. He graduated jump school in 1963 and originally had orders to go to the 101st Airborne, but he joined a new unit called the 173rd Airborne Brigade Separate as a medic.

In March 1966, three days before the actions that earned him the Medal of Honor, his platoon participated in a mission called Operation Silver City. His reconnaissance platoon kept encountering caches of weapons, and they had a bad feeling about where they were at. A huge firefight erupted about 3 kilometers from their position, and they discovered their sister platoon was surrounded. Rascon described it as if the Americans were in a mini football field and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) were in the stands, with reinforced battalion strength. They noticed the NVA was setting up an L-shaped ambush and all hell broke loose. They could hear the enemy yelling, blowing whistles, then gunfire; they could smell the cordite from the explosions; they could see their teammates getting hit.

A machine gunner went down on the trail, but the gunfire was too intense. Rascon tried twice to get him and was finally successful on the third attempt. When he reached Thomas, the machine gunner, Rascon laid across his 6-foot-4 frame to protect him. Rascon was hit in the hip, but noticed that a nearby machine gunner was running low on ammo. He grabbed the larger Thomas and dragged him off the trail before running to the other machine gunner, Gibson, and patching up his gunshot wound to the leg. Rascon then ran, untouched, back to Thomas, who was now dead, retrieved two bandoliers of ammo, and returned to Gibson. A hand grenade exploded, destroying Rascon’s face, nose, and neck.

When he regained composure, Rascon noticed that an extra M-60 barrel with 400 rounds of ammunition was 10 yards from the enemy. He decided to grab it instead of letting it fall into enemy hands. Other members of his platoon were wounded, including a M-79 grenadier who was shot in the back. Rascon retrieved the barrel and provided suppressive fire as the NVA broke contact. Being the only medic on the team, Rascon provided medical assistance to his friends before attending to his own wounds. He survived and made it home. He was awarded the Medal of Honor in 2000 and retired from the Army as a lieutenant colonel.

Sergeant First Class Louis R. Rocco

Louis Rocco had a tough upbringing and was part of a local gang in Albuquerque, New Mexico, when he was arrested for armed robbery. The judge gave him a decision: jail or the military. Rocco chose the Army. He served two tours in Vietnam and was a decorated medic for his role in rescuing eight severely wounded Army of the Republic of Vietnam soldiers. The partner forces that serve alongside American servicemen are just as valuable as their own teammates. Warrant Officer Louis Rocco joined the MEDEVAC helicopter as it stormed to the injured partner forces.

As they descended on the landing zone, their helicopter was ripped apart by enemy fire and began to spin uncontrollably into an open field. Rocco suffered from a fractured wrist and a bruised back. The helicopter became an inferno, and Rocco personally carried an unconscious pilot 20 yards across open terrain to a large tree. He repeated this action three more times, despite being burned from the flames, and administered emergency medical aid. The next day, two helicopters were shot down trying to retrieve them, but a third swooped in low and fast, picked them up, and took off.

Sergeant First Class Jose Rodela

Jose Rodela was another Hispanic veteran who was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Obama in 2014. He was one of the few who was present that day to personally accept the honor. The native of Corpus Christi, Texas, had already served 14 years in the U.S. Army before he would endure 18 hours of continuous combat as the company commander for 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne) in Phước Long Province, South Vietnam, on Sept. 1, 1969.

According to his citation: “That afternoon, Sergeant First Class Rodela’s battalion came under an intense barrage of mortar, rocket, and machine gun fire. Ignoring the withering enemy fire, Sergeant First Class Rodela immediately began placing his men into defensive positions to prevent the enemy from overrunning the entire battalion. Repeatedly exposing himself to enemy fire, Sergeant First Class Rodela moved from position to position, providing suppressing fire and assisting wounded, and was himself wounded in the back and head by a B-40 rocket while recovering a wounded comrade. Alone, Sergeant First Class Rodela assaulted and knocked out the B-40 rocket position before successfully returning to the battalion’s perimeter. Sergeant First Class Rodela’s extraordinary heroism and selflessness above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit and the United States Army.”

Captain Euripides Rubio

Captain Euripides Rubio was one of five Puerto Ricans to receive the Medal of Honor. In Tay Ninh Province, Republic of Vietnam, Rubio and members of the 1st Battalion, 28th Infantry, were ambushed by a large North Vietnamese force. The battalion outpost was hit with accurate mortar fire and rifle grenades. When the explosions ceased, automatic weapons fire tore up their fortifications; Rubio was struck twice when he moved from the safety of cover. Despite his wounds, he distributed ammo to areas that were hit the hardest, provided medical attention to others, and, as a communications officer, assumed command of a rifle company, placing soldiers in the best spots to repel the attack.

While his teammates were being evacuated, a smoke grenade fell danger-close to allied positions, and Rubio moved to throw the grenade to mark Viet Cong positions for an airstrike. When he reached the smoke grenade, he fell to his knees as he was hit by gunfire. He grabbed the already smoking grenade with his bare hands, rose to his feet, ran within 20 yards of the enemy, and hurled it into their midst. Unfortunately, on Nov. 8, 1966, the same day of his heroism, he was declared KIA.

Specialist Héctor Santiago-Colón

Héctor Santiago-Colón hailed from Puerto Rico and moved to New York City with his family in 1960 with the intention of joining the New York City Police Department. At that time, they were only selecting military veterans, so he enlisted in the U.S. Army and served a tour in Vietnam. He had just proposed to his fiancee, and she was eagerly waiting for his safe return. While serving with the 1st Cavalry Division, Santiago-Colón acted as a perimeter sentry and gunner to a mortar platoon. He heard movement in the night as the enemy approached through the dense vegetation. Santiago-Colón alerted his teammates to prepare their positions for an ambush when a gunshot rang out — and then the night sky was filled with muzzle flashes.

Alongside fellow sentries, Santiago-Colón repelled the assault using hand grenades and anti-personnel mines. An enemy NVA soldier crawled deep inside their perimeter and lobbed a hand grenade into Santiago-Colón’s foxhole. He grabbed the hand grenade with his bare hands, turned his back to his teammates, and absorbed the explosion into his stomach. He was declared KIA on June 28, 1968, and was posthumously awarded the MOH two years later.

Staff Sergeant Elmelindo Rodrigues Smith

Elmelindo Rodrigues Smith lived in Hawaii and joined the U.S. Army in 1953. He was stationed at various bases around the world, including Okinawa, Japan, where he met a Hawaiian-born WAC (Women’s Army Corps) named Jane; the pair soon married. His tour to Vietnam began on July 23, 1966, as a platoon sergeant for 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry, 4th Infantry Division. On Feb. 16, 1967, he posthumously earned the MOH.

A portion of his citation reads: “With complete disregard for his safety, P/Sgt. Smith moved through the deadly fire along the defensive line, positioning soldiers, distributing ammunition and encouraging his men to repeal the enemy attack. Struck to the ground by enemy fire which caused a severe shoulder wound, he regained his feet, killed the enemy soldier and continued to move about the perimeter. He was again wounded in the shoulder and stomach but continued moving on his knees to assist in the defense. Noting the enemy massing at a weakened point on the perimeter, he crawled into the open and poured deadly fire into the enemy ranks. As he crawled on, he was struck by a rocket. Moments later, he regained consciousness, and drawing on his fast dwindling strength, continued to crawl from man to man. When he could move no farther, he chose to remain in the open where he could alert the perimeter to the approaching enemy. P/Sgt. Smith perished, never relenting in his determined effort against the enemy.”

Captain Jay R. Vargas

Jay Vargas was born in Arizona to a Italian mother and Hispanic father in 1938. His three brothers also served during World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. During an interview, he said he was given three golden rules by his brothers about being a Marine: “The first was always set a good example and set your standards high. Always take care of your men was number two, regardless if it’s peacetime or combat. Number three was a tough one, it was never ask a Marine to do something that you wouldn’t do yourself.”

He joined the Marine Corps and became the Commanding Officer and Executive Officer of 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, 3rd Marine Division. Near the village Dai Do, in the Republic of Vietnam during the spring of 1968, Vargas and his unit were engaged with small arms, mortars, artillery, and rocket fire. He immediately maneuvered his element through 700 meters of open rice paddy.

They set up on two hedgerows on the enemy’s perimeter but were pinned down. Vargas led his men on an assault destroying three machine gun emplacements despite being peppered with fragmentation grenades. The enemy left the target to coordinate their forces and sent probes and counterattacks throughout the night. The enemy was repelled again, and the Marines were reinforced with further troops by the morning.

It was Vargas’ actions in the following days that earned him the Medal of Honor. His citation reads: “The marines launched a renewed assault through Dai Do on the village of Dinh To, to which the enemy retaliated with a massive counterattack resulting in hand-to-hand combat. Maj. Vargas remained in the open, encouraging and rendering assistance to his marines when he was hit for a third time in the three-day battle. Observing his battalion commander sustain a serious wound, he disregarded his excruciating pain, crossed the fire-swept area, and carried his commander to a covered position, then resumed supervising and encouraging his men while simultaneously assisting in organizing the battalion’s perimeter defense.”

Vargas said that once one proves themselves as a leader, “they’ll follow you through the gates of hell.” Vargas retired from the Marines in 1993 as a colonel.

Captain Humbert Roque Versace

Humbert Roque “Rocky” Versace graduated from West Point in 1959. He served as an Army Ranger during the Korean War and then a tank platoon commander, where he achieved the rank of captain. He volunteered to serve a tour in Vietnam as an advisor with 5th Special Forces Group. During his free time, Rocky worked in a Vietnamese orphanage and was impacted by the humanity the Vietnamese people shared with him. After his second tour to Vietnam, he planned to join the priesthood and return to the orphanages in South Vietnam.

Two weeks before he was scheduled to return home, Rocky volunteered for a dangerous mission during which he was shot three times through his legs and provided cover so his unit could retreat. He was captured by the enemy alongside 1st Lieutenant Nick Rowe, known for his post-war survival techniques taught to special operations forces. His captors put them in tiny bamboo cages infested with insects, and their wounds were left to rot. The NVA didn’t abide by the Geneva Convention rules, and Rocky refused to accept their propaganda tricks.

The enemy held him for two years — and despite daily beatings trying to break his will, Rocky never wavered. As his refusal was praised quietly by other POWs, the captors executed him. Thirty-seven years after his death, Rocky became the first POW Medal of Honor recipient when President George W. Bush awarded him posthumously in 2002.

First Sergeant Maximo Yabes

Maximo Yabes dropped out of Oakridge High School in Oregon to join the U.S. Army. He was assigned to the 4th Battalion, 9th Infantry, 25th Infantry Division and deployed to Vietnam. Located northwest of Saigon, Yabes and his platoon were responsible for providing security for a team of Army Engineers who were bulldozing a path between a village and plantation. The Viet Cong recognized this was the perfect opportunity to attack, and on Feb. 26, 1967, waves of enemy soldiers breached their concertina wire. The enemy identified the command post bunker and hurled several grenades into the opening.