Dog tags hang from the Iraq/Afghanistan Dog Tag Memorial at the Museum of the Forgotten Warrior outside of Beale Air Force Base, California, Nov. 10, 2011. The memorial was built to honor all of the men and women who had been killed during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars as of Oct. 30, 2011. It includes 6,296 individual dog tags. Photo by Staff Sgt. Jonathan Fowler/US Air Force.

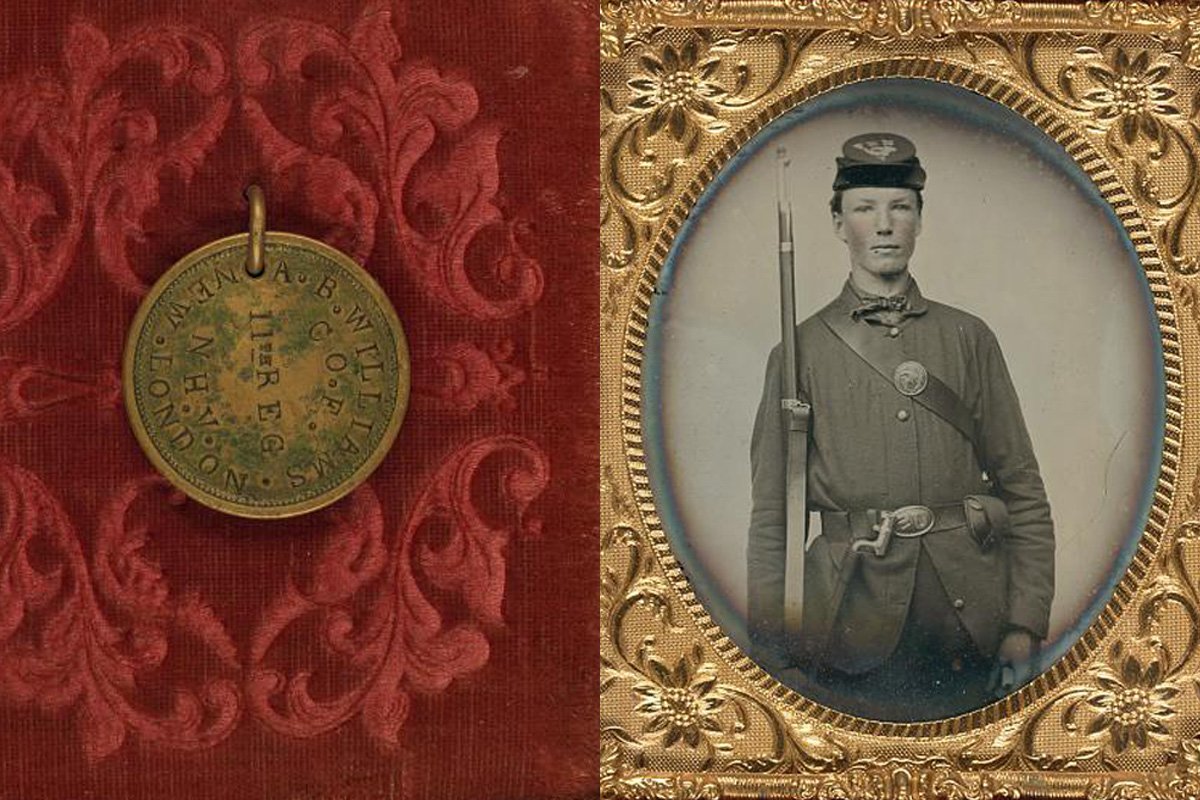

During the Civil War, American service members worried how their bodies would be properly identified if they were killed in action: a fair concern, considering more than 40% of the Civil War dead remain unidentified.

To ease their minds, some soldiers tattooed their epitaphs on their bodies, while others made personalized dog tags out of paper or stitched them onto clothing. These identification symbols were also fashioned into coins or carved into wood chunks and hung around their necks. It was their way to assist the living when no official process was in place.

The unofficial practice took some time to gain traction and, although the identification method is popularly known as “dog tags” these days, the term wasn’t coined until at least 1936. The nickname stems from a matter that doesn’t even involve the military. William Randolph Hearst, a newspaper magnate and yellow journalism pioneer, published an article in an attempt to undermine support for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. Hearst heard about a proposal for the newly formed Social Security Administration to give out nameplates for personal identification — adding all workers would receive treatment as if they were dogs, and private information would no longer be confidential. He called these identification plates “dog tags.”

“This news was widespread and easily caught on,” said Ginger Cucolo during a presentation called “Dog Tags: History, Stories & Folklore of Military Identification” at the Library of Congress. “We believe that that is where dog tags and the label did stick.”

US service members continued the tradition following the American Civil War. In 1899, at the end of the Spanish-American War, the first request to field service members with ID tags came by an Army chaplain in the Philippines. Chaplain Charles C. Pierce, who was in charge of the Army Morgue and Office of Identification, recommended soldiers wear circular disks to identify those injured or killed in battle.

In 1906, the Army issued a general order requiring aluminum disc-shaped ID tags to be worn under soldiers’ field uniforms. These ID tags were stamped with a soldier’s name, rank, company, and regiment and were attached to either a string or chain.

“It was during World War I that the thought of burying the soldiers where they fell became important to many family members even if on foreign soil,” Cucolo said. “When Teddy Roosevelt’s son lieutenant Quentin [Roosevelt] was killed, he requested that, ‘where the tree falls, let it lie.’ 30,000 Americans from this war are buried in one of eight cemeteries in Europe while 47,000 were returned to the United States.”

The ID tags became mandatory in 1917 amid World War I for all US combat troops. Individual service branches had their own versions.

“These first tags were oval, of Monel metal (a patented corrosion-resistant alloy of nickel and copper, with small amounts of iron and manganese), 1.25 inches wide and 1.5 inches long,” states a Naval History and Heritage Command article about the Navy’s version of dog tags. “Perforated at one end, a single tag was to be worn around the neck on Monel wire ‘encased in a cotton sleeve.’”

One side of the tag had an etched fingerprint of the right index finger, and the other side had “U.S.N.” and the sailor’s personal information.

However, after World War I, the US Navy discontinued wearing dog tags. According to a 1925 Navy personnel manual, identification tags were only issued “in time of war or other emergency, or when directed by competent authority, individual identification tags shall be prepared and worn by all persons in the naval service.”

In World War II, the tradition picked back up, and each dog tag was mechanically stamped with name, rank, service number, blood type, and religion.

“By 1969, the Army began to transition from serial numbers to Social Security numbers,” Katie Lange of the Department of Defense writes. “That lasted about 45 years until 2015, when the Army began removing Social Security numbers from the tags and replacing them with each soldier’s Defense Department identification number.

“The move safeguarded soldiers’ personally identifiable information and helped protect against identity theft.”

While DNA analysis can identify anonymous remains, dog tags are still standard issue for US service members today. In an effort to honor the legacy of those killed during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Museum of the Forgotten Warrior outside of Beale Air Force Base in California has an outdoor exhibit featuring thousands of individual dog tags. The Iraq/Afghanistan Dog Tag Memorial, as of 2011, contains 6,296 individual dog tags.

Read Next:

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.