How Combat Artist Howard Brodie Sketched His Way From War to the Courtroom

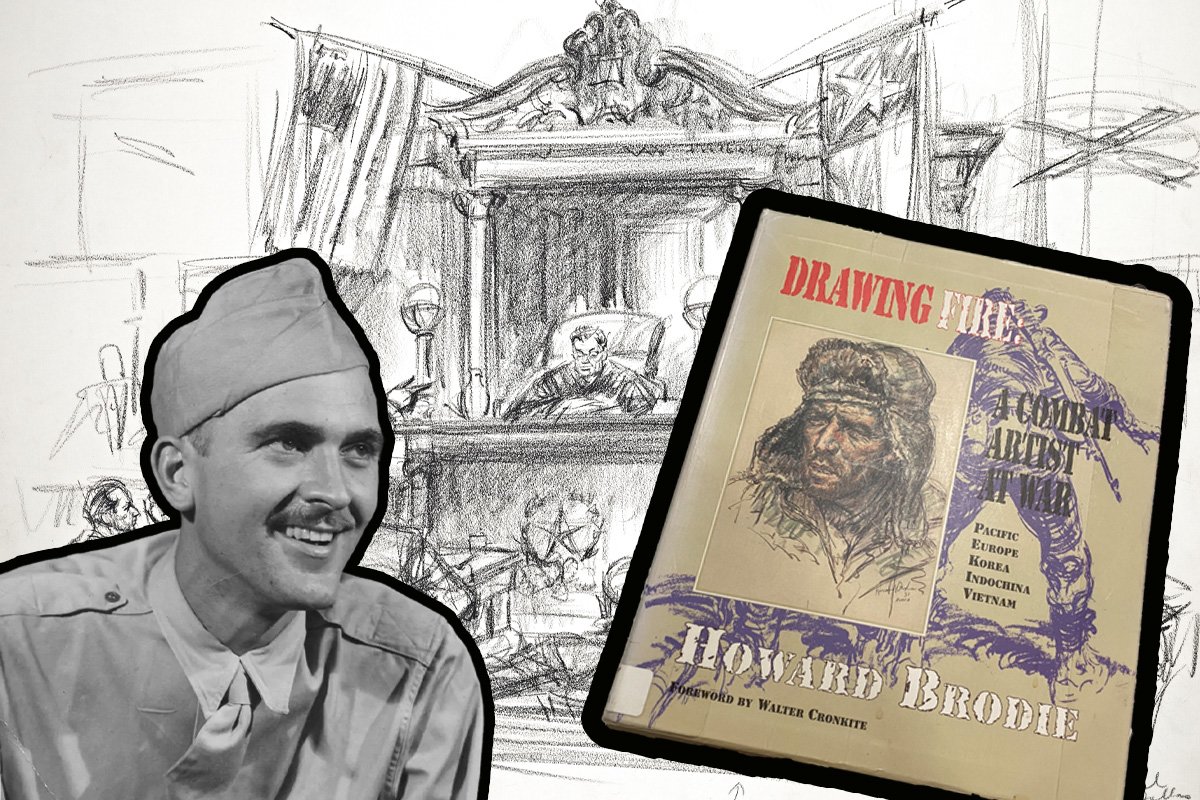

Howard Brodie’s artwork covered battlefields from World War II to Vietnam. Later, he became famous for his striking courtroom sketches. US Army photo. Courtroom sketch of the Jack Ruby trial courtesy of Elizabeth William’s book The Illustrated Courtroom: 50 Years of Court Art. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

In February 1964, as Jack Ruby stood trial for the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald — the man accused of assassinating President John F. Kennedy — a legendary artist sat in the back of the Dallas courtroom, sketching away with his pencil. Howard Brodie — already a renowned combat artist — marked his drawing of the Ruby trial with arrows and notes indicating peculiarities no still image could capture.

“The best courtroom illustrations are simply those that convey most directly and honestly exactly what the artist sees,” Brodie said.

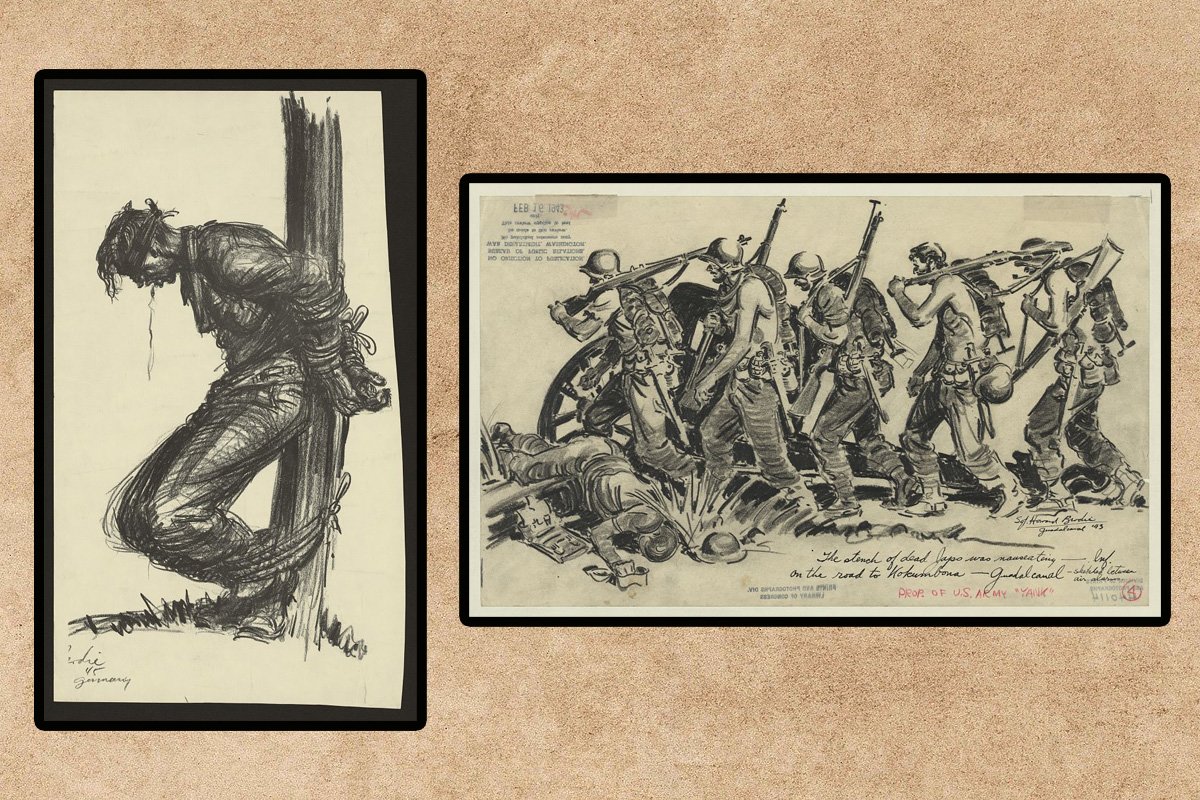

A once in a generation storyteller, Brodie first gained fame for his work as a combat artist in World War II. He left behind his sports beat at the San Francisco Chronicle to sketch soldiers in the Pacific in the waning days of the Guadalcanal campaign. Brodie — himself a US Army soldier — didn’t carry a weapon. Instead, he used his hands to craft stories about the harrowing experiences of American service members.

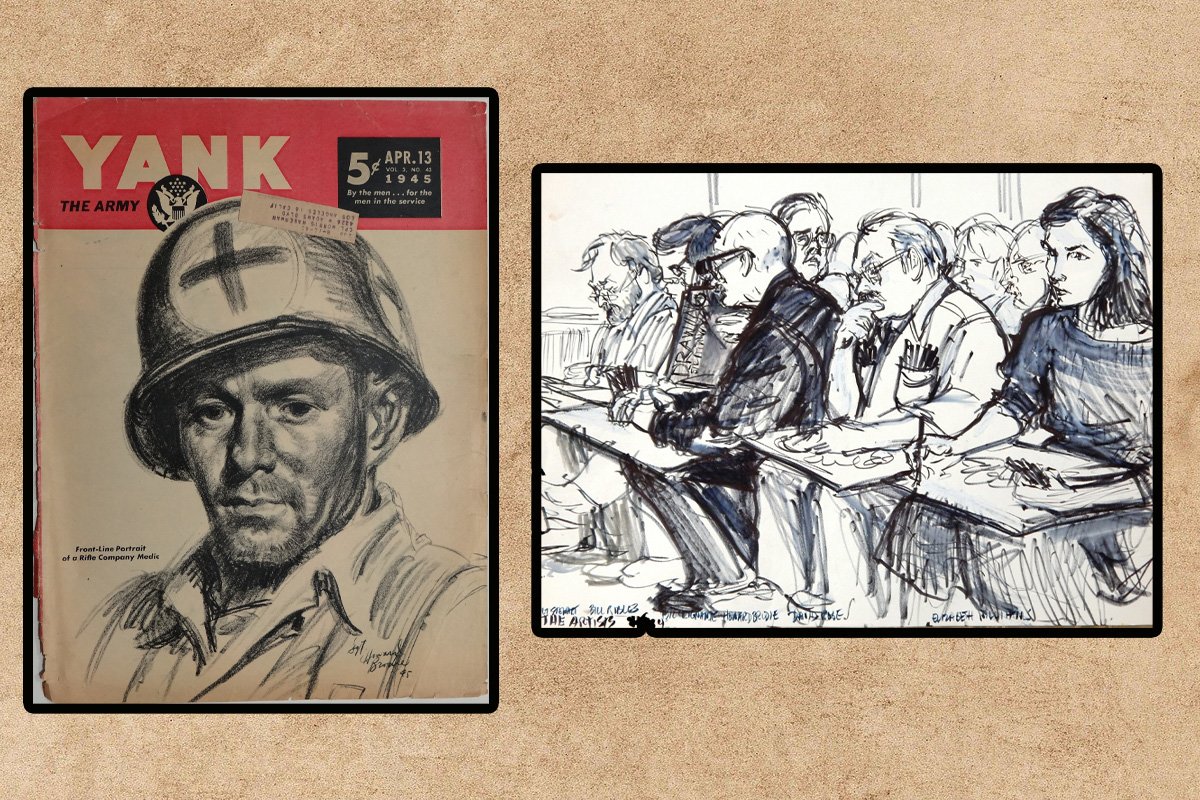

As US troops marched across France, Belgium, and Germany, Brodie’s emotionally moving artwork was published in Yank: then the most popular publication in circulation for military personnel. Brodie was even awarded the Bronze Star with Valor during the Battle of the Bulge for “aiding the wounded, and coolness under fire.”

During that battle, Brodie released one of the most moving pieces of art of his career.

“My most searing memory of any war was during the Battle of the Bulge, when Germans posing as GI’s infiltrated our lines,” Brodie reflected. “I heard we were going to execute three of them […] A defenseless human is entirely different than a man in action. To see these three young men calculatingly reduced to quivering corpses before my eyes really burned into my being. That’s the only drawing I’ve ever had that’s been censored. All coverage of the execution was censored.”

After the war, Brodie contacted his network of fellow artists and began work with CBS Evening News. Before long, America and its allies were thrust into more conflicts. Brodie went on to serve as a combat artist in Korea, French Indochina, and Vietnam.

In between trips to foreign battlefields, Brodie covered the most high-profile court cases in the United States, often attending the Supreme Court, drawing the debates leading to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Chicago Seven political activists trial, and the Watergate hearings.

Elizabeth Williams — a woman with more than 40 years of courtroom sketch art experience and a colleague and personal friend of Brodie’s — told Coffee or Die Magazine why Brodie believed in on-the-spot drawings for capturing the realness of a moment.

“A lot of illustrators use photo reference, which is very typical, but when you’re in a courtroom, or you’re on a battlefield, you’re not using photos if you’re drawing something immediate,” Williams said. “When he started out with the Ruby trial, he did everything in black pencil because it was a black-and-white television show. When you look at early courtroom art in the ’60s and ’70s, the artwork was predominantly black and white, but in the ’70s and ’80s, color was everywhere.”

While covering the Ruby trial, Brodie etched his way into history for being among the first courtroom artists to sketch for television. With the absence of cameras in federal courthouses, artists like Brodie and Williams provided the public a window into otherwise-closed courtrooms.

“In the ’80s and ’90s, you needed to have a picture in by 8 o’clock at night,” Williams told Coffee or Die. “Now it’s immediate because everyone is waiting for it. You’re working under a lot of stress and duress.”

Despite the growing pains of the job, Brodie continued to work until health issues forced his retirement in the late 1990s. He wrote the book Drawing Fire: A Combat Artist at War (1996).

“Howard Brodie is such a legend in the news business that Walter Cronkite, who coined the label Artist-Correspondent especially for him, called him, ‘The ultimate journalist whose pen speaks a thousand words,'” Williams wrote.

Brodie died in 2010 at the age of 94 and is survived by his widow, Isabel, his son, Bruce, and his daughter, Wendy.

Read Next: The Vietnam Combat Artist Program: The American Soldiers Who Documented War With Art

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.