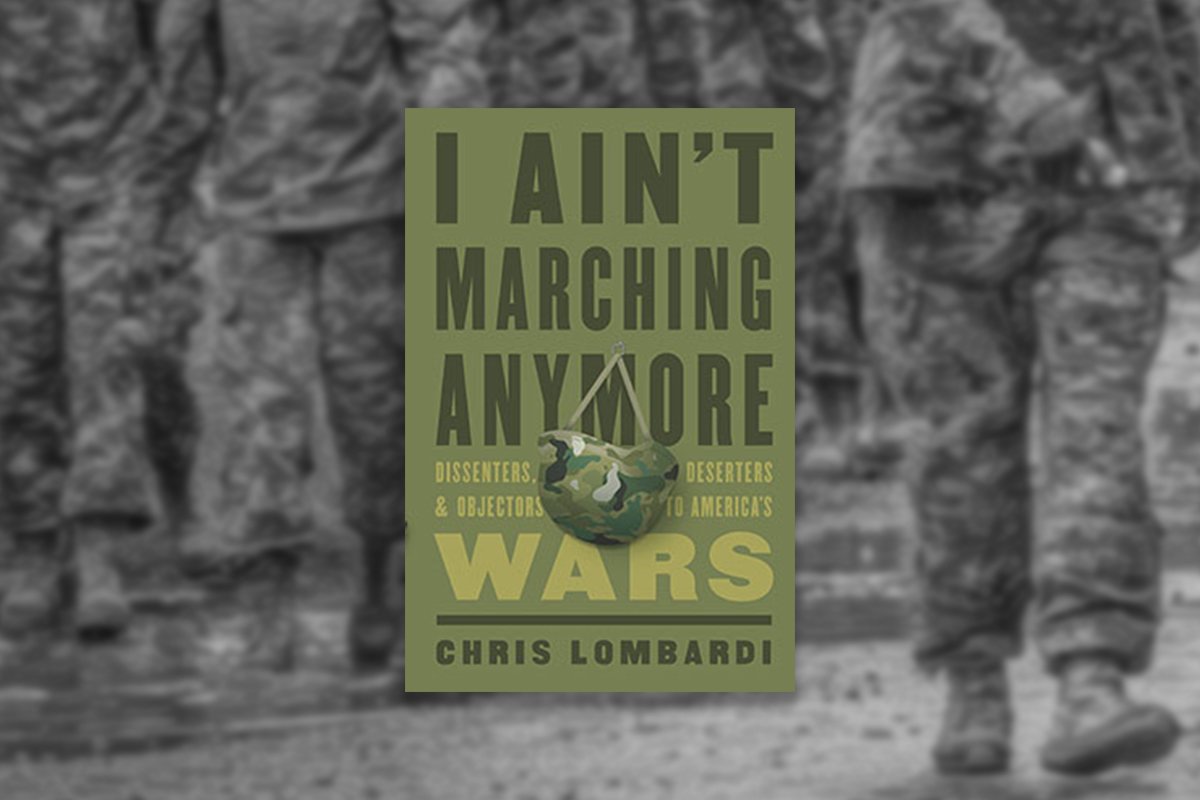

Review: Onward, Dissenting Soldiers, in ‘I Ain’t Marching Anymore’

Glance at the subtitle that pairs deserters with dissenters and deserters with objectors, and you might scratch your head in bewilderment. What characteristics do a dissenter and a deserter share? What has a conscientious objector (CO) in common with a deserter? Each has myriad motivations, and one of the three classifications is illegal.

If you disregard the expediency of the cover wording and open the book, you might discover the faces, facts, and figures that explain the premise behind the grouping. Maybe even enough information to evoke your empathy for, or at least your better understanding of, the people who wear a uniform and dissent publicly.

“Publicly” is the key in I Ain’t Marching Anymore. The main title is borrowed from Phil Ochs’ 1964 protest song: “Call it peace or call it treason,” Ochs says, in lyrics not quoted in the book. Lombardi covers 266 years of protest in 304 pages, and her work could serve as textbook for a college-level survey course on the history of protesters in uniform — if there were an index for academics and for the rest of us who try to keep track.

“At every touchstone in the American Revolution soldiers claimed their newish role as citizen by exercising their right to dissent,” Lombardi writes. “Conscientious objector” was coined in 1650, she reports.

And for a while the Constitution included support for dissent from military service.

James Madison’s initial draft of the Second Amendment says “no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms shall be compelled to render military service in person.” The proposal was dumped.

Since 1754, citizens have united against military actions (or the lack of them) for reasons regarding racism, injustice, discrimination, and the practical matter of getting paid. Capt. Daniel Shays, for example, led a rebellion in 1786, “asserting his right to seek redress against postwar economic inequality.”

In 1815, 400 Kentucky troops in New Orleans deserted Gen. Andrew Jackson midbattle. Why? Perhaps they “heard peace had been declared, but it was more likely a mix of hunger, confusion, and the fear of being mutilated.”

But overall, principles of injustice seem to be the principal reason for commitment to social disagreement. Standing up to any cause depends on the fortitude and the philosophy of the individual service member, and Lombardi relies on the voices of protesters to illustrate her points.

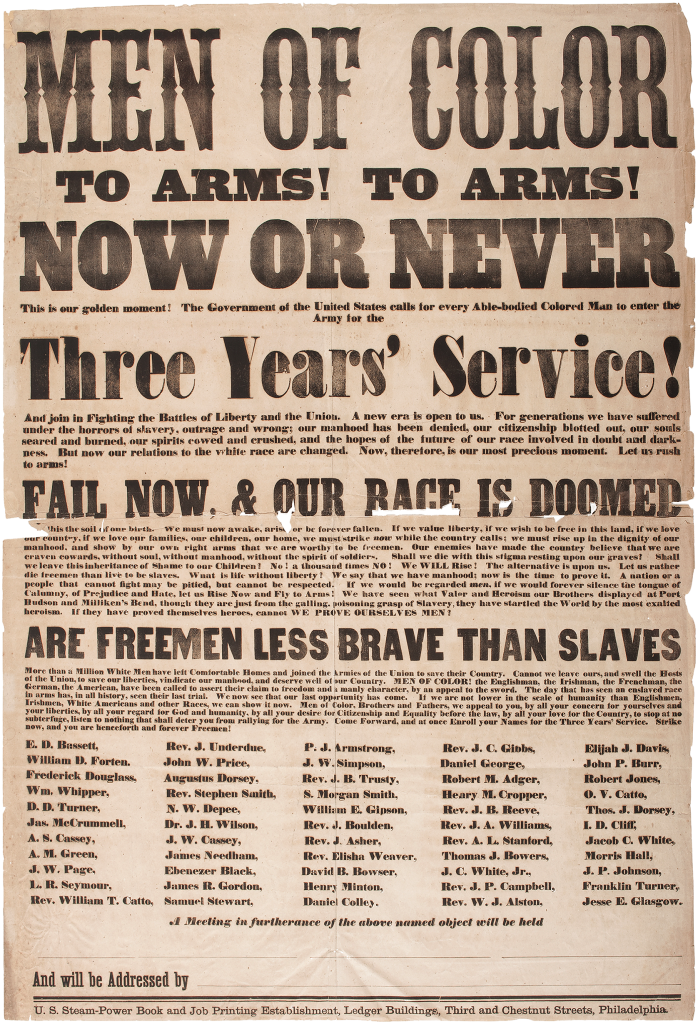

In the Civil War, Frederick Douglass’ son Lewis fought with the 54th Massachusetts, helping Black soldiers “establish a reputation as a fighting regiment.” But after the Spanish-American War, Lewis wrote that “injustice to dark races prevails. The people of Cuba, Porto Rico, Hawaii and Manila know it well as do the wronged Indian and outraged black man in the United States.”

Half a century later actor Lew Ayres’ claim was a matter of conscience. He had starred in 1930’s All Quiet on the Western Front, the anti-war movie based on Erich Maria Remarque’s 1929 timeless and recommended novel about World War I.

In World War II, Ayres surprised Hollywood by claiming conscientious objector status — one of the 37,000 COs processed by Selective Service by war’s end. During Ayres’ mandated alternate service, he provided first aid “to men pressed into service cutting timber” for the war effort.

The Korean War saw 4,300 registered COs, and the Vietnam War put dissent on front pages, TV screens, and tips of tongues. Fred Marchant, a 23-year-old Marine from Rhode Island serving in Okinawa, was shocked by photographs of dead bodies at My Lai and believed his own service made him complicit in “taking other people’s lives.”

He became one of 17,000 service members discharged as a CO during the war.

In 2003, a Marine Corps lance corporal applied for status as “the first Iraq War CO,” and by 2007, “soldier-dissenters were starting to take on the military’s racism and sexism,” forming organizations such as Iraq Veterans Against War and Service Women’s Action Network. At Fort Drum in upstate New York, soldier Chelsea (then known as Bradley) Manning “cheered” efforts to end Congress’ “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.

In 2010 intelligence analyst Manning leaked what she called “one of the most significant documents of our time” to WikiLeaks. The reaction was mixed. “Most in the military saw Manning as a traitor,” Lombardi says delicately and without attribution. She gives Manning at least eight pages and says her case “brought together almost all the 21st Century threads this book has been watching,” a literary convenience of dubious relevance.

But whatever your politics, Marching serves up a quick compendium of conscientiousness in the military customs of the country. (Astute readers will find no mention of Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, who was captured by the Taliban after he deserted his unit in 2009.)

Lombardi worked for the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors, has been “writing about war and peace for 20 years,” and maintains a journalistic style — if not a journalist’s need for objectivity — throughout the narrative.

“If there’s gonna be a revolution, it’s going to happen because of anti-war veterans,” she says at the end. “Fundamental, progressive change has been escorted into American life with such figures,” and her book gives those women and men their voice and their due.

I Ain’t Marching Anymore: Dissenters, Deserters, and Objectors to America’s Wars by Chris Lombardi, The New Press, 304 pages, $28. Politics and Prose bookstore will stream a conversation between Lombardi and Navy veteran Jonathan W. Hutto, who figures in I Ain’t Marching Anymore and is the author of Antiwar Soldier: How to Dissent Within the Ranks of the Military (2008), beginning at 6 p.m. Eastern on Jan. 18.

Noted but Not Reviewed

Here are other recent works of nonfiction that Coffee or Die readers might find of interest:

Unsinkable: Five Men and the Indomitable Run of the U.S.S. Plunkett by James Sullivan, Scribner, 416 pages, $30. The story of five sailors and the Navy destroyer that “sustained the most harrowing attack on any Navy ship by the Germans during World War II.”

Rock Force: The American Paratroopers Who Took Back Corregidor and Exacted MacArthur’s Revenge on Japan by Kevin Maurer, Dutton, 303 pages, $28. From the prolific author who co-wrote No Easy Day, the autobiography of former Navy SEAL Matt Bissonnette (“Mark Owen” is a pen name) and his role in the Bin Laden raid.

Once a Warrior: How One Veteran Found a New Mission Closer to Home by Jake Wood, Sentinel, 320 pages, $27. Team Rubicon’s co-founder Wood, a Marine veteran of Iraq and Afghanistan, writes about his last decade and the success of the disaster-response organization.

War: How Conflict Shaped Us by Margaret MacMillan, Random House, 336 pages, $30. Combat journalist Dexter Filkins calls the book a “richly eclectic discussion of how culture and society have been modeled by warfare throughout history.”

How Ike Led: The Principles Behind Eisenhower’s Biggest Decisions by Susan Eisenhower, St. Martin’s, 400 pages, $30. The general and president’s granddaughter, who wrote a biography of her grandmother, Mamie, presents a look at how the strategist relied on facts for his decision-making.

J. Ford Huffman has reviewed 400-plus books published during the Iraq and Afghanistan war era, mainly for Military Times, and he received the Military Reporters and Editors (MRE) 2018 award for commentary. He co-edited Marine Corps University Press’ The End of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (2012). When he is not reading a book or editing words or art, he is usually running, albeit slowly. So far: 48 marathons, including 15 Marine Corps races. Not that he keeps count. Huffman serves on the board of Student Veterans of America and the artist council of Armed Services Arts Partnership and has co-edited two ASAP anthologies. As a content and visual editor, he has advised newsrooms from Defense News to Dubai to Delhi and back.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.