Uniformly Excellent: The Importance of America’s Noncommissioned Officers

As part of a large, strategic-level staff section, I currently work with junior enlisted soldiers, noncommissioned officers (NCOs), warrant officers, commissioned officers, Department of the Army (DA) civilians, and contractors. The manning in my small division within this organization is almost evenly split between field grade officers, senior warrant officers, contractors, and DA civilians. Although none work directly for me, I often interact with soldiers and NCOs in other divisions in the course of my duties.

One day I casually mentioned to a senior NCO in another division that I would be having my DA photo taken in the near future. This exchange caused me to reflect on the impact that NCOs have on the U.S. Army and on me personally — the things that make the U.S. Army’s NCO Corps “Uniformly Excellent.”

NCO: Oh, so you have your DA Photo for your promotion board tomorrow. Who’s going with you?

Me: What do you mean, “Who’s going with you?” No one’s going with me — this is a DA photo not a Soldier of the Month board or an Article 15 reading.

NCO: <stares in NCO>

Me: ?

NCO: Okay, sir. Well, who’s inspecting your uniform before you go down there?

Me: Well, I‘m going to ask the guys in the shop to look it over, but I’ve been in the Army over 23 years and I don’t really need an inspec–

NCO: <stares in NCO>

<stares in NCO>

<STARES IN NCO>

Me: … you are?

NCO: <smiles>

In U.S. Army parlance, a “DA photo” is the photograph that goes into one’s official military file, and it is essential for things like promotion boards and command selections. The photo is taken in the formal Army Service Uniform, which most of us old-timers refer to as “dress blues.”

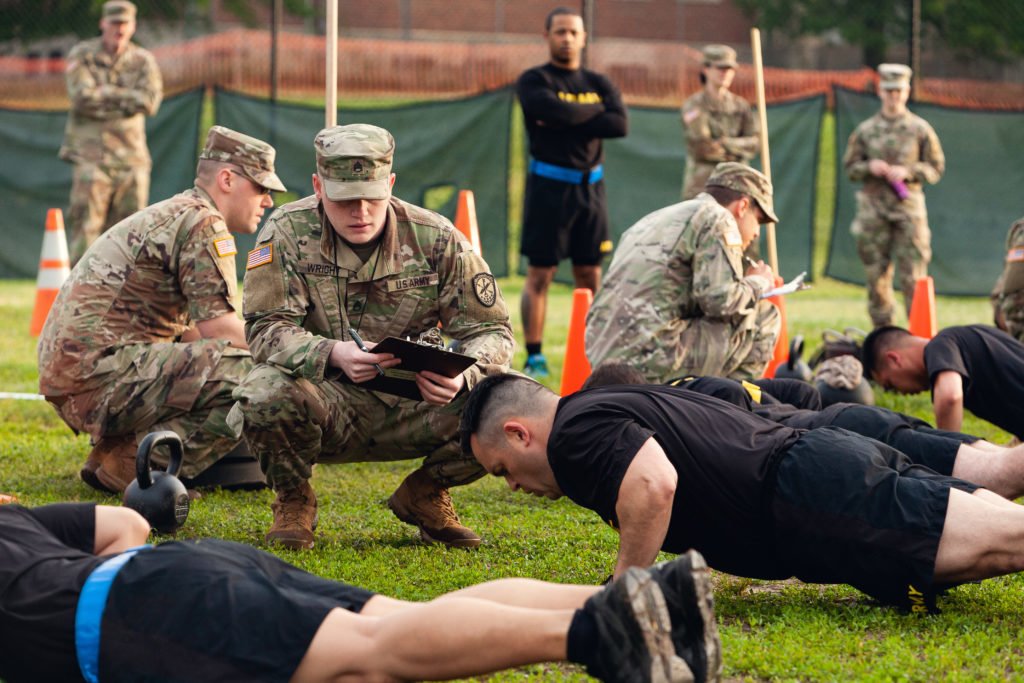

People make a lot of judgments based on this photo: Does the person look fit? Do they look “commander-ly”? Is this an NCO I’d want to have in front of troops? What sex and race are they? Are they not wearing any awards they have earned — or, more importantly, are they wearing any decorations that they haven’t earned?

Because of the extreme importance of this photograph, it is taken very seriously. It’s quite common to bring a helper to the studio to make sure everything is straight and professional-looking. It’s similar to having a squire on hand at a jousting match — you probably could handle it by yourself, but it’s much easier to have another set of hands. Many soldiers do all the prep work beforehand, but the preferred method is to bring someone who can help with last-minute adjustments and make sure everything is straight, even, and crease-free before the photographer starts snapping pics.

I had a board coming up, but I wasn’t competitive for the next rank, so my DA photo didn’t really matter. Nonetheless, it’s an expectation of the profession, so I dutifully booked an appointment and prepared my uniform. About an hour before my appointment, I closed the door to my office and changed into my dress blues. I then asked my civilian deputy, a former Army E7, to look it over. After that, I called the NCO who had offered to inspect my uniform, and he came to my office. We made final adjustments, and then I drove to the photo studio.

It was useful to have a knowledgeable NCO look over my uniform before my DA photo. I hadn’t done that for my previous photo, and I made one rather conspicuous mistake and a handful of minor ones (see photo below). It’s not like I attended the State of the Union address with my ribbon rack inverted, but I could have used a little NCO love. Hopefully I managed to avoid any issues this time.

The photographer was a total pro, helping me stand so that my hands held in my sleeves (to prevent wrinkles) and ensuring my arms were cocked in a certain way to show “waist gap” (i.e., to show I wasn’t fat — I didn’t even know this was a thing). She even turned me so that the seven “combat stripes” on my right forearm were clearly visible.

Partway through the shoot, I realized that this was probably the last DA photo I would have taken. As I said, I will not get picked up for promotion, and I have a few years left until mandatory retirement. It was a weird feeling to recognize that I would probably never have to go through this rigmarole again. As I got ready to leave, a master sergeant and a staff sergeant were standing in the reception area fussing over a young female Signal Corps captain, making sure every pin was properly placed, that all of the spacing was 100 percent within regs, and that every bit of lint was culled from her spotless dress blues jacket and skirt.

It reminded me of similar experiences I had early in my career, and it hit me, once again, how important NCOs are — in the Army in general and in my career in particular. As I passed, I touched the master sergeant on the shoulder and said, “Hey, Master Sergeant, this” — gesturing to the entire group — “is great. Thank you.” The staff sergeant seemed a little confused, but the master sergeant understood. “Roger, sir. Thank you,” he replied.

I was a little emotional on my drive back to the office, thinking about the interest the two NCOs showed in the professional success of that young captain and feeling grateful for the investment NCOs made in me during my 20-plus years in the Army. I remember First Sergeant Donlin from when I was commanding an intelligence company in the Second Infantry Division in Korea on 9/11. I remember Sergeant First Class Devine from my three deployments to Afghanistan as the S2 for 2/160th SOAR. Master Sergeant Rhinehart was my detachment sergeant on my first tour in Iraq, back when I commanded the Group MI Detachment and the Group Support Company in 5th Group. I can never forget Sergeant First Class Watson and Petty Officer Gordey from my time in JSOC. And there are many more.

But the NCO who I remember most is my first platoon sergeant, Sergeant First Class Ellery Edwards, who was actually my platoon sergeant twice when I was an infantry-detailed officer in Delta Company, 1-327 in the 101st Airborne. He taught me what right looks like, both for officers and for NCOs. I will be forever grateful for those lessons.

The NCO who took the time to help me with my DA photo uniform wasn’t “my” NCO, and I wasn’t “his” officer. But he cared enough about the profession — and about me — to personally ensure I got this right because he knew how important it was. NCOs do this kind of thing all the time, every day. “No one is more professional than I,” the NCO Creed states — and for almost all of my career, that’s what I’ve seen from the NCO Corps.

No matter how long an officer has been in uniform, and whether it’s about uniforms or any other issue, he or she would be well-suited to solicit and consider the advice and counsel of NCOs. Not every NCO is great, of course, and “always do what your NCO says” is bad advice, especially for young officers. But it has been my great privilege to experience great NCOs across the duration of my career. After more than 20 years, I’m comfortable saying that excellence is uniformly distributed throughout the NCO Corps, which is a great strength of our Army and a great benefit to its officers and Soldiers.

Thank you, NCOs.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Faint is a military intelligence officer with the United States Army and holds a master’s degree in International Relations from Yale University. He taught International Relations at West Point for three years, and also served in the 5th Special Forces Group, the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, and the Joint Special Operations Command, to include seven combat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. You can reach him at [email protected], and read more of his work on West Point’s Modern War Journal or on The Havok Journal. This article reflects his personal opinion based on his education and experience, and is not an official position of the U.S. Army or the U.S. Government.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.