Inside a Secretive Joint US-China Intelligence Unit, Dubbed the “Rice Paddy Navy”

The Rice Paddy Navy was a scrappy group of river pirates, peasants, coastwatchers, saboteurs, a feared Chinese Secret Service General who ruled with an iron fist, and a reasonably confident US Navy officer accompanied by a team of handpicked sailors and Marines. Described as one of the best-kept secrets of the Second World War, this exclusive spy ring was created over a cup of coffee.

As World War II escalated in Europe with the invasion of Poland in 1939 and Imperial Japan began to rattle their sabers, US Navy Commander Milton E. Miles and China’s military attaché Major Xiao Bo conceptualized strategic plans in Washington, D.C., in the event they were thrust into war.

While the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was able to build a sustainable footprint in Europe largely by coordinating with Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) and other allied nations resistance groups, these units struggled to build rapport with their Chinese counterparts in the Far East.

The Friendship Project

After the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor, plans were set into overdrive. Miles was sent from Washington, D.C., on a solo flight to Chungking, China, to meet with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek — the understood leader of Nationalist China — Bo, and General Dai Li (sometimes referred to as Tai Li or the “Himmler of China”) just five months later. They realized they would need to prepare for a large-scale amphibious assault and were in desperate need of a global intelligence network, as well as strategic remote weather stations in the Pacific.

At this meeting, Miles learned his friend Bo was more than a Chinese military attaché enjoying coffee and exchanging sea stories in his office three years prior — in fact, he was an agent under Li’s intelligence service relaying these plans back to Li as it happened.

Li proposed an unusual offer that was a good deal for both sides. In a meeting held in May 1942 in a small village surrounded by fields of flooded rice paddies (American sailors soon donned the name because their new work environment brought them ashore opposed to fighting their battles at sea), Li put everything up front knowing the intentions of the Americans. He stated: “The United States wants many things in China. Weather reports from the north and west to guide your planes and ships at sea, information about Japanese intentions and operations, mines in our channels and harbors, ship watchers on our coast, and radio stations to send information. I have 50,000 good men … if my men could be armed and trained, they could not only protect your operations but work for China, too.”

In June 1942, both Miles and Li signed the treaty that formed the Sino-American Cooperative Organization (SACO — pronounced “socko”) and shook hands sealing their “friendship.” Li assumed the role as SACO’s director and Miles became deputy director, allowing each the power to veto the other’s plans.

“Where the OSS and SOE failed to build a connection, Miles thrived.”

Under their leadership, the duo each made an effort to instill their forces to adopt each other’s culture (they had their riffs), judge each man by their actions, and, above all, use every asset at their disposal no matter how irrational it appeared on the surface. Li noticed early on that Miles was the solution to his problems as they each wanted to do the same thing: work as one to torment Imperial Japan. Where the OSS and SOE failed to build a connection, Miles thrived.

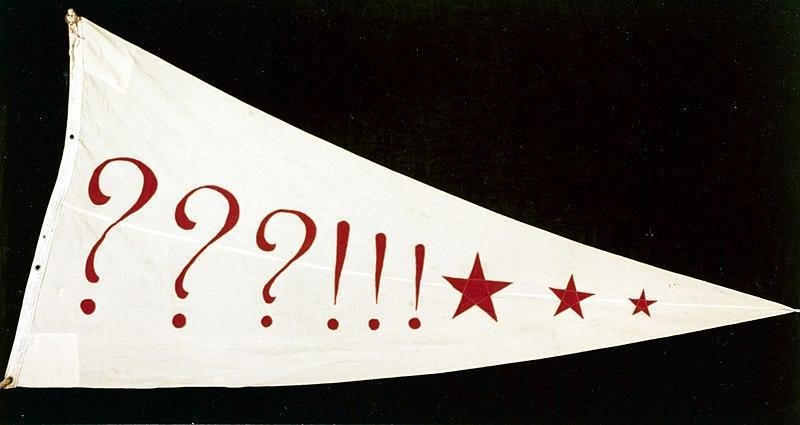

“What the Hell” Pennant

The US Navy utilizes alphabet flags and numerical pennants to signal allied forces while communicating at sea; all other vessels follow the International Code of Signals. Miles first used his infamous pennant when he was a junior officer aboard the USS Wilkes in 1934. As ships challenged each other and often conducted evasive maneuvers to avoid collision, many of the sailors on board would exchange profanities and middle fingers.

In a tongue-and-cheek manner, Miles would raise his pennant every chance he could to get his message across. The pennant contained three exclamation marks, three question marks, and three asterisks, simulating the way writers censored curse words.

On one mission in 1939, Miles commanded the USS John D. Edwards destroyer and was tasked with an operation to locate American missionaries on Hainan Island — a tropical beach in the South China Sea — that the Japanese Navy had surrounded.

When Miles arrived off the coastline, he saw a Japanese fleet pounding the island with artillery. One Japanese destroyer in particular noticed an American ship in the distance and hoisted a flag with the international translation of something resembling, “You don’t belong here, so leave.” Focused on the mission, Miles hoisted his infamous “What the Hell” pennant and continued toward shore.

Linda Kush, the author of “The Rice Paddy Navy: U.S. Sailors Undercover in China,” who spoke about this instance at the International Spy Museum, recalled what happened next, sealing Miles’ fate as a calculated renegade to lead the SACO. The Japanese admiral, still unable to decode the pennant, was so appalled to see one lone ship continue toward the beach defying his commands that he stopped the attack and sent a reconnaissance craft to close the distance within earshot.

As the craft approached Miles, the officer shouted, “You can’t anchor here!” and Miles immediately replied, “You’re right, I’d rather anchor closer to shore,” and slowly anchored his boat between the Japanese ship and the island. After locating and bringing aboard the missionaries later in the day, the Japanese admiral was furious and demanded that Miles translate his pennant. Miles’ quick thinking and wit led him to respond to the admiral’s inquiry by saying that the admiral needs a new codebook because his must be out of date.

With Miles at the helm of the SACO, the unit adopted the pennant and wore it as a patch of honor on their uniforms. Fitting the mold, sailors and Marines would often hear the phrase, “What the hell is the US Navy doing here?” — sealing the unit’s reputation forever.

SACO Training and Operations

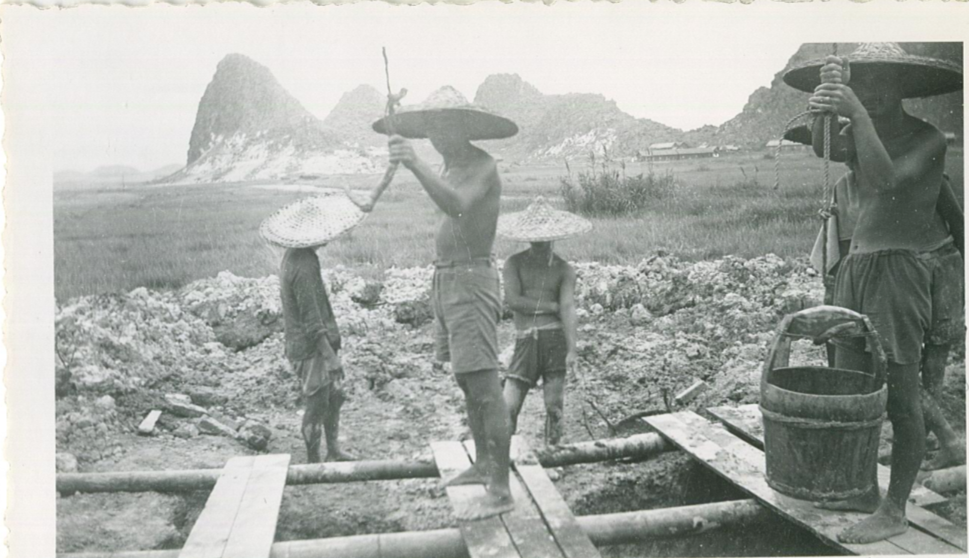

Miles appointed trusted sailors to create camps and units where Americans trained Chinese guerillas at improvised eight- to 12-week schools where they learned the art of espionage, small arms, hand-to-hand fighting techniques, demolitions, scouting, and patrolling. Everyone had a purpose — from the elite American advisors to the local peasants — and each made notable contributions throughout the war.

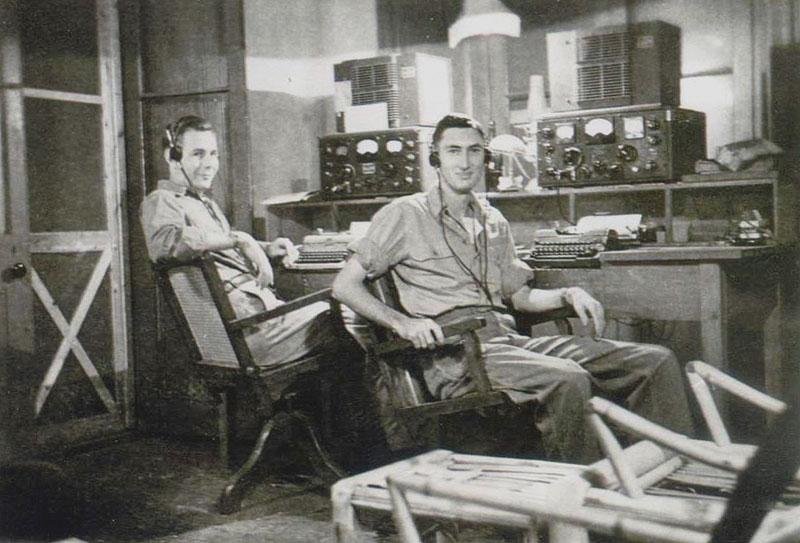

These camps yielded quick successes as each group of Chinese guerillas was led by a small contingent of American advisors. Each camp had different responsibilities; those inland tried to position themselves as close to the enemy as possible to conduct ambushes, assassinations, and sabotage on key officers and infrastructure. Other groups built remote radio stations to monitor Japanese communications and decipher codes. Those that operated by sea specialized as spies, coastwatchers, and aerographer’s mates, using their training to study naval schemes, predict weather patterns, and provide detailed reconnaissance for future operations.

Not all members of the Rice Paddy Navy received formal training, but their efforts were just as important. These were the members of the community that were given guidance and instructions to act if called upon. In villages, “bike girls” were used for their speed and ability to blend in with locals. At times throughout the war, American OSS agents and allied aviators would be captured and brought to Shanghai. The SACO, fearing they’d be executed, sent these women with an extra portable bike that folded in a backpack to intercept them. Once the bike girls reached their target, they’d bribe the captors, hand over their extra bike to the agent, and speed away to safety.

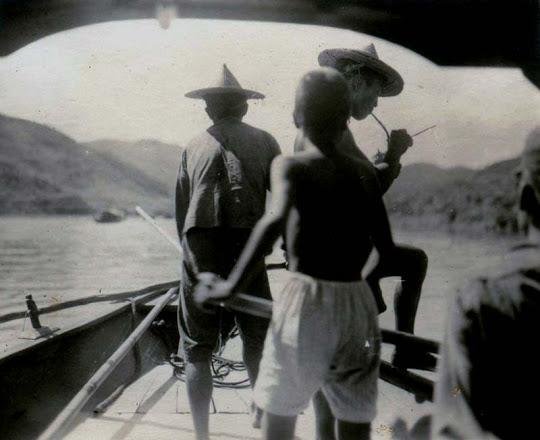

Along the South China Sea, Li had connections with river pirates and warlords and enlisted them to launch secret missions to gather intelligence. They also provided assistance with boats, weapons, and manpower to protect US Navy coastwatchers (though the Navy wasn’t thrilled about this arrangement). As many of the coastwatching camps were constructed in pirate territory, it was a good cover to shield their visibility in the area. In return, it gave the pirates legitimacy among Nationalist China behind closed doors.

In just three years spanning from 1942 to 1945, the SACO were able to rescue 76 aviators that were shot down, kill an estimated 71,000 Japanese soldiers, and built an army of nearly 97,000 Chinese guerilla fighters from scratch. Some even went on to serve with the famed Merill’s Marauders in Burma.

In all, 18 camps were organized across China, Burma, Indochina, and parts of India. Over 70 weather stations were erected and provided useful intelligence. Miraculously, of the 2,964 active SACO members, only five were killed during the entire war. Following its conclusion, Li died in a plane crash in 1946 and the SACO disbanded the same year. At the turn of the 21st century, their tales of heroism, nearly 50 years later, are finally being recognized.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.