Inside the Korengal, Families Split Between Taliban, Afghan Army, and ISIS

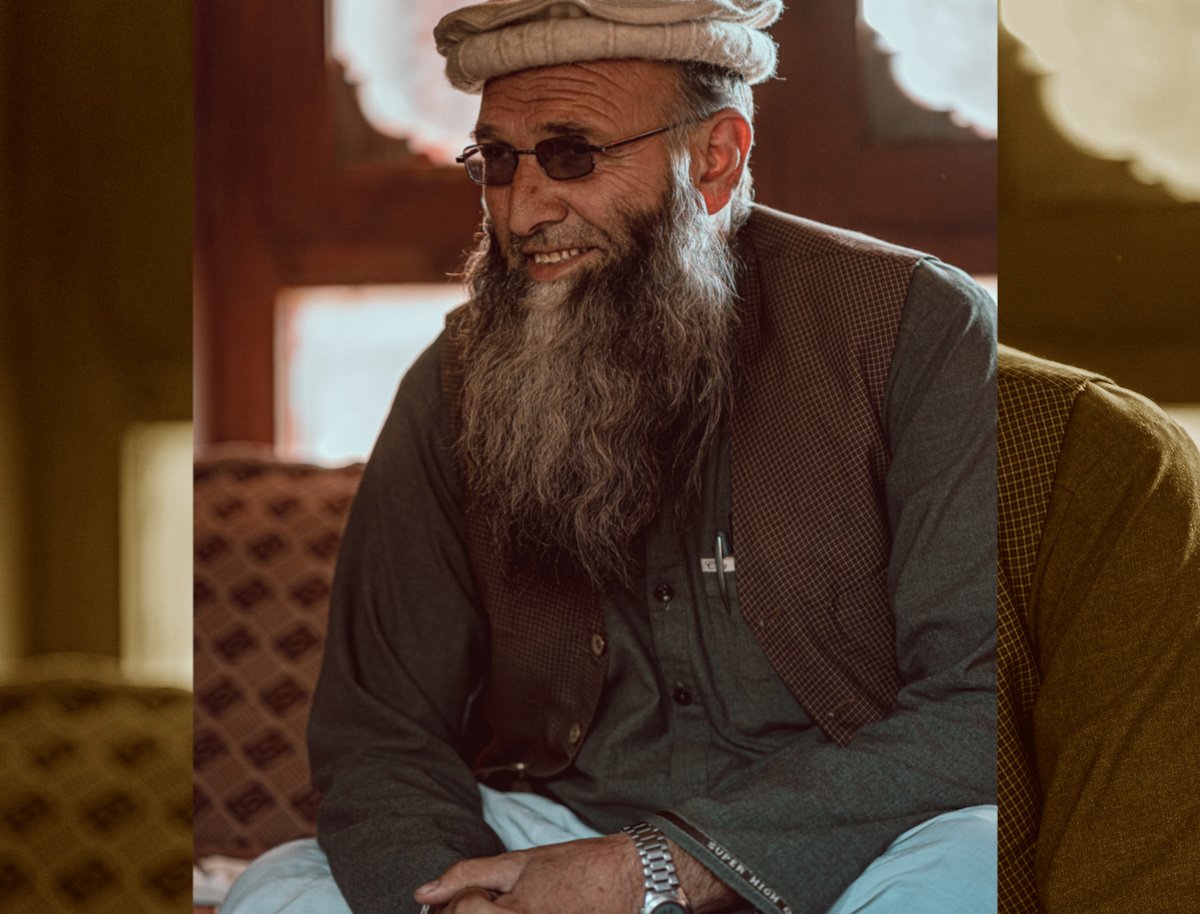

Abdul Khaliq, the 45-year-old local school principal in the Korengal Valley. Photo by Jake Semkin for Coffee or Die Magazine.

INSIDE THE KORENGAL VALLEY, KUNAR PROVINCE, Afghanistan — It has been ominously termed the “Valley of Death.”

To reach the valley shielded by towering hilltops and thick forests, one must sputter for hours from the Kunar provincial capital of Asadabad on broken, rock-coated mud tracks winding over rugged terrain and mountain ledges. Then, finally, a sturdy yet abandoned military base comes into view. Mud brick homes speckle the landscape, and there’s a sense of being trapped inside a 13th-century time capsule.

There is little left to show for the blood, sweat, and tears Americans spent here; the US pulled out of the valley in 2010. Halfway through the bitter Afghanistan war, reports indicated that almost three-quarters of all bombs dropped in Afghanistan were in and around the jagged Korengal, which empties into the Pech River.

The Taliban claim to have complete control inside the Korengal, a typically hard-line, Salafist-adherent valley, but sentiment on the ground tells a starkly different story. It has morphed into a unique place where almost every family has some former Taliban, some former Afghan National Army (ANA) soldiers, and others who have pledged allegiance to the ISIS-K affiliate, colloquially known as Daesh.

“Here, if the father was a Talib, then the son was a soldier in the ANA. Then the brother and uncle would be Daesh. But somehow, everyone is a splinter group of the Taliban,” explains one 33-year-old Korengal local who asked to be identified only as Safi. “That is how it is here.”

Several nephews were part of the ANA in his own family, and two of his brothers were Taliban. One brother was killed during the war with the US, and the other surrendered to Afghan government soldiers. Another nephew became a policeman, and another joined ISIS-K.

Some families fight internally, and others don’t dispute their differences, Safi says.

And for 16-year-old Irfan, who lives at the foot of the valley and meets me secretly in an abandoned workshop — where we sit on broken car seats and sip tea until a prying Taliban comes to investigate what is happening — his family has been pulled apart by the conflict that has claimed his entire childhood.

“My dad was Taliban, but he died fighting years ago. So then my brother became ANA, and my other brother belonged to no one,” the rail-thin, timid teen boy says. “But he died a few months ago. A howitzer (field artillery) was fired and landed in front of the house, just as my brother was coming out.”

The challenge is still to stay away from any of the competing armies and insurgencies — but Irfan remains determined that there must be more to life.

“I want to be a doctor; I want to make something of myself,” he continues. “But I can only go to school sometimes; mostly, I have to work and do daily chores.”

Safi, the 33-year-old, remembers that his home was raided 15 times by US forces, yet he holds no grudges, no bitterness. He belongs to no fighting force, clearly disoriented by the boundless bloodletting that has scarred his memories as he struggles to make ends meet as a daily laborer. But it’s evident that, for him, the recent Taliban takeover is akin to disaster.

“Nobody here has served the province; only the previous government did some construction works that benefited the people,” Safi vows. “Everybody else here is working for their own benefit and has taken guns and artillery just to kill each other. It is all a game of benefits.”

After the US withdrew in 2010, the inaccessibility of the furrowed topography paved the way for outside insurgencies to come and go. The valley’s villagers all have searing stories to tell about the six months or so that they spent entrapped by ISIS occupation.

“It was really hard. The fighting was always there. The robberies were always there. They forced people to go out of their homes, and any wife of a Taliban was made to leave the area,” one village elder, a 55-year-old named Mohammad, tells me.

According to Abdul Khaliq, the 45-year-old local school principal, life was far worse under ISIS than with the Americans, as they would “rob houses and take people into custody.” Khaliq and several other teachers were abducted by the ISIS fighters and detained for around two months.

“Nobody has done such cruel actions to teachers. For two months, we were held in a dark room and could never see the sun,” he recalls. He was able to escape when a fight broke out between the Taliban and ISIS, providing a window of opportunity to flee.

And in the words of Salam, a 65-year-old elder: “We have seen the Russian revolution, the Americans — but what ISIS did here, we have not seen anything like it.

“They sent every kid and woman out of their homes, and we were pleading with them,” Salam says.

While the Taliban commanders dotting the area claim that they were the ones to have defeated ISIS-K around a year ago, Safi quietly explains that it was the Afghan army who did the heavy lifting and that the Taliban were the ones begging for help after the brutal, black-clad outfit took control — kicking the Talibs out — several years ago.

But in addition to the mosaic of allegiances even within a family, the lush valley bears its own starkly independent spirit — a deep desire for nobody but their own tribal elders to lay down the law of the land.

Mohammad, the 55-year-old villager, stresses that the Korengal people “got together to beat them,” which is how Daesh eventually left.

Yet below the mountain range, inside the Korengal, in nondescript homes by the roadside, ISIS families blend in with the rest of the Kunar community.

“When the Taliban was here (during the time of the last government), they were saying they had control of 80% of the country, but they were not implementing Islamic rulings inside the Korengal. So that is why we stood up and started implementing Islamic rulings like cutting hands here,” one 24-year-old, proud ISIS-K fighter named Nazifullah proclaims to me. “Whoever goes against Islam, we are against them.”

Some Korengalis still yearn for the era of the US occupation inside the Korengal. In the wake of the “forever war,” it has been easy for pundits, policy wonks, and the media to lambaste the US “hearts and minds” efforts as amounting to little. However, the efforts are not entirely lost on the locals.

“Life was good when Americans were here,” Mohammad tells me, undeterred by the Taliban fighters glaring over his shoulder. “Economically, it was good; people were busy. But after they left, the economy got weak.”

But for many, life amid war amounted to life like a rock stuck in a hard place.

“If we stood with the Taliban, Americans would kill us. And if you stood with Americans, the Taliban would kill us,” noted elder Mohammed Ali, who is around 70. “We couldn’t do anything at that time.”

The late war photographer Tim Hetherington infamously called the expansive acreage of the northeastern Kunar province the “most dangerous terrain for U.S. forces anywhere in the world.” Yet to the naked eye, the voluptuous forest and ceaseless stream of pine trees still carry a graveyard of haunting memories.

“The Korengal is a war location in itself. There are jungles and mountains, so people can just hide anywhere and attack,” Mohammad explains. “That is why it is such a hard place.”

The American war inside the Korengal was comparatively short but traumatic. More than 50 American troops died in the Korengal, with the majority of casualties between 2006 to 2009. The gritty war documentary Restrepo follows a US platoon at a firebase deep in the valley, taking near constant enemy fire for months. In the entire Global War on Terror, including Iraq and Afghanistan, 23 American soldiers have been awarded the Medal of Honor for extraordinary bravery and heroism in combat. Seven — almost one of every three — were earned in the Korengal or in neighboring valleys and towns along the Pech River.

Indeed, if there ever was a patch of Afghanistan that embodied the unfortunate idiom “the graveyard of empires,” it is inside the Korengal. The Institute for the Study of War deemed the area “the deadliest place in Afghanistan,” in which the “Korengalis have successfully fought off every attempt to subdue their valley, including the Soviets in the 80s, the Taliban rule in the 90s, and […] the U.S. military.”

While the lavish landscape provided crafty cover for a multitude of US high-value targets linked to al Qaeda and the then-Taliban insurgency, today it’s a pivot point for ISIS or Pakistan Taliban operatives to sneak across the porous Pakistan border.

The situation in the valley remains chillingly fragile — as if something, or someone, could erupt at any time.

“People are at the top of mountains and always expecting that ISIS will fight us,” Salam says softly. “Incidences will happen, but we expect them not to come completely back.”

The Korengal Valley Outpost, or KOP, that once housed American troops is now an eerily quiet place submerged in the hilltops with small shops built in huts where soldiers once slept. Locals carve wood from dusk until dawn, chickens peck the dust where US helicopters once landed, and fierce light falls between the trees.

“We want peace. We want good construction and assistance to develop the country, that is my hope. We could make some money in the previous government, and people were busy working, not fighting. But since the fall, no work has come. Prices for everything have gone up,” Safi says. “Nobody speaks the truth here, and that is why the country is not being built. If international assistance comes forward, there is still hope and possibilities.”

Read Next:

Hollie McKay is a foreign correspondent, war crimes investigator, and best-selling author. She was an investigative and international affairs/war journalist for Fox News Digital for over 14 years where she focused on warfare, terrorism, and crimes against humanity; in 2021 she founded international geopolitical risk and social responsibility firm McKay Global. Her columns have been featured in publications including the Wall Street Journal and The Spectator Magazine. Her latest book, Only Cry for the Living: Memos From Inside the ISIS Battlefield, is now available.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.