Milley Raises Hopes for Interpreters, but Advocates See a Looming Nightmare

US soldiers meet with Afghan leaders with an interpreter’s aid. Photo courtesy of No One Left Behind.

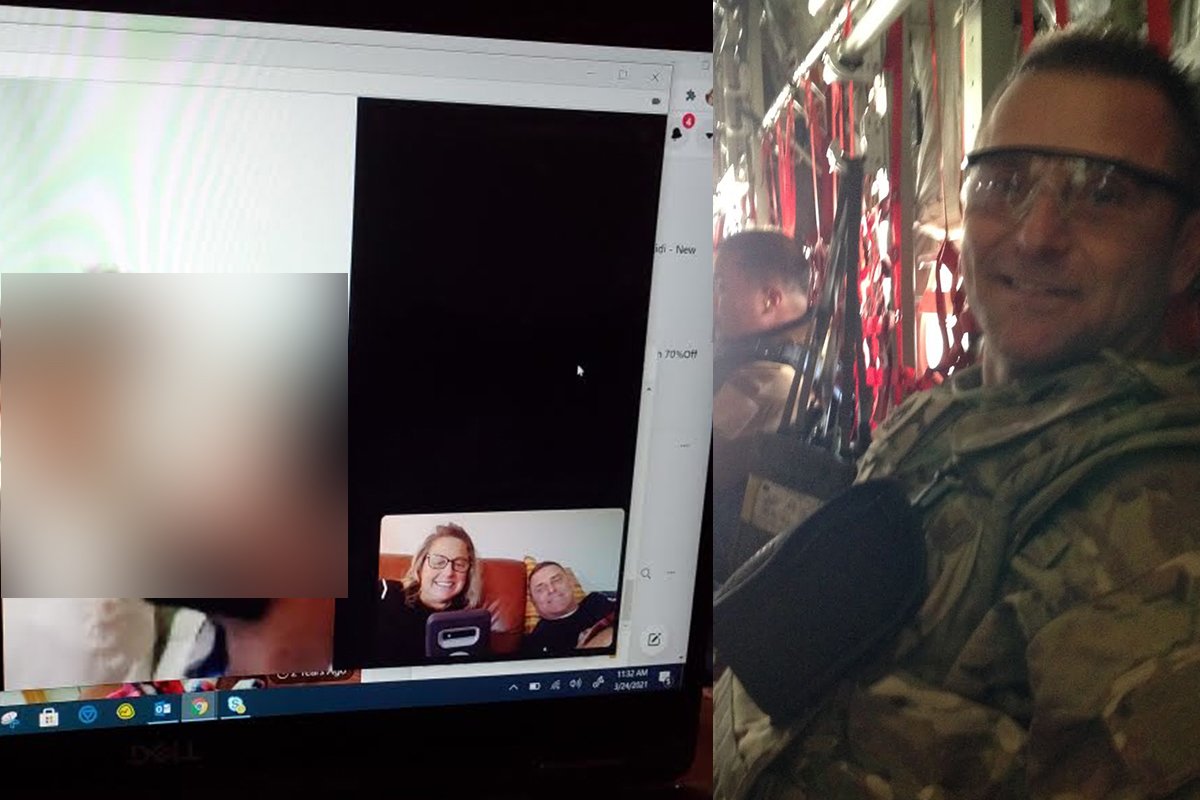

After 36 years in the Army, former Sgt. Maj. Gerald Keen retired to a peaceful horse farm on Lake Michigan. But two or three times a week, he opens a FaceTime tab and dives back into the war. His interpreter, who calls himself Rehime to protect his identity, is still in Gardez. The two worked together almost every day during Keen’s deployment in 2016.

“He was at all the same tables as I was, with the generals, where decisions were being made,” said Keen.

Rehime, Keen says, is the same age as his own youngest son but speaks five languages — English, Pashtun, Arabic, German, and Italian. In meetings, Rehime often translated not just with fellow Afghans but with coalition partners from Europe.

Today he lives in a family compound, working as an IT contractor for the last remaining vestiges of the coalition, as much a whiz with computers as he was at languages.

“This kid is smart,” Keen told Coffee or Die Magazine. “He’s fighting the fight every frigging day.”

When they talk, Keen asks about Rehime’s kids. Keen and his wife, Lynette, help pay for their schooling now, five years after Keen returned home. Then, Keen says, he figured Rehime would need months, maybe a few years, to clear the hurdles for a Special Immigrant Visa, or SIV, the US program meant to bring former interpreters and contractors to the US. It requires two years of service, a background check, and other administrative checks.

But five years later, Rehime is one of close to 20,000 former US interpreters and contractors who are stuck in limbo from the 20-year war. And getting them all out in a mass evacuation might take a logistical effort as big as the entire US withdrawal.

And now — with a likely midsummer pullout of all US troops looming — time is almost out.

“There’s a bounty on his head from the Taliban,” Keen says. “They’re hunting him. We got to get him out.”

After years of what many veterans of Afghanistan describe as cruel inattention from leaders, Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Mark Milley set off a wave of hope in the community Wednesday, telling Defense One, “We recognize that there are a significant amount of Afghans that supported the United States, supported the coalition. And that they could be at risk, their safety could be at risk. […] We recognize that a very important task is to ensure that we remain faithful to them, and that we do what’s necessary to ensure their protection, and if necessary, get them out of the country, if that’s what they want to do.”

Milley offered no details nor a guarantee in the interview, but his comments, activists say, are the first with a note of urgency from a top US official.

“It’s great,” said James Miervaldis, who sits on the board of directors for No One Left Behind, an advocacy group for Afghan interpreters and contractors. “But planning is one thing and executing is another. We’re at 25% of the withdraw this week. This all goes hand in hand.”

Advocates like Miervaldis and Keen have lobbied to have eligible interpreters and their families moved out of Afghanistan while their visas are being processed, either to a friendly nearby country or a US territory like Guam. However, the State Department said this week that no plans are underway for Guam.

“We are processing special immigrant visas in Kabul and have no plans for evacuations at this time,” a spokesperson for the State Department told The Guam Daily Post.

Noah Coburn has a unique connection to US interpreters and other contractors. As a graduate student, he lived independently in a village an hour outside the US airfield at Bagram, and then worked for several NGOs, living a total of five years in Afghanistan. Now a political anthropologist at Bennington College, Coburn said he knows dozens of US contractors waiting for visas, or who have already fled.

“The SIV has so failed that if you’re an Afghan in danger, you are not applying for it,” he said. “Instead, you’re paying someone to smuggle you through Iran to get to Europe.”

Coburn said the database of contractors waiting for a visa that No One Left Behind keeps includes former workers currently in 30 countries, most of whom have fled as their paperwork moved forward.

“My Afghan contacts are mostly sitting down as families and discussing, ‘How much money do you have, what can you liquidate?’ Some are selling their houses.”

The closest parallel in recent US history to the Afghan pullout may be the Vietnam boatlift, when the military moved 100,000 refugees in a matter of months.

“This is worse,” Coburn says. While Vietnam saw an exodus by sea, the only mass transportation available in Afghanistan is overland or by air.

Miervaldis says the 20,000 applications do not include families, who will also have to leave. “We’ve worked with three administrations, six secretaries of defense, and four secretaries of state,” he said. “This is the team to get us across the finish line but we think there are about 35,000 who could — should — be in the US tomorrow. They are absolutely going to be targeted.”

Coburn wonders if the number isn’t closer to 80,000.

“There’s a real possibility of Taliban teams going house to house,” he said. “We pulled off the airlift out of Vietnam 50 years ago. Considering the extent of our effort, this seems eminently doable.”

A quick math check, though, suggests that a worst-case evacuation could tax the airlift ability even of the US. A C-17, the Air Force’s primary heavy lift aircraft, can carry about 100 paratroopers. If families were loaded en masse for an evacuation, even carrying little more than a suitcase each, it could take sorties in the high hundreds to move the current backlog.

For comparison, CENTCOM said last week that as much as 25% of the US withdrawal had been accomplished with 160 C-17 flights spread over a month.

Still, Milley’s comments Wednesday appeared to signal a shift in US resolve.

“I’m more encouraged today than a week ago,” said Coburn. “But I was in a pretty dark place a week ago.”

Read Next:

Matt White is a former senior editor for Coffee or Die Magazine. He was a pararescueman in the Air Force and the Alaska Air National Guard for eight years and has more than a decade of experience in daily and magazine journalism.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.