Inside the Secret World of Human Intelligence Collectors at the ‘Interrogation Olympics’

Human intelligence collectors conduct a field interrogation on a role player from "Donovia" at Fort Bragg in August. US Army Photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney/XVIII Airborne Corps Public Affairs.

With one guard at the ready and another directing the detainee, the interrogator puts the detainee on his knees at gunpoint, ankles crossed, hands interlaced behind his head.

The interrogator then searches the man, making sure to get up the sleeves, in the side pockets of the pants, and the waistband of his jungle-patterned uniform.

“What unit are you with?” asks the interrogator, a squad leader with the Army's 525th Expeditionary Military Intelligence Brigade.

“I don’t want to tell you that,” the man says, uncooperative.

A HUMINTer from the 525th Expeditionary Military Intelligence Brigade conducts a field interrogation while on objective. The soldier speaks to another 525th EMIB soldier playing the role of "Donovian Soldier," a member of the fictional enemy force, for the purposes of the competition. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney.

The 525th team has already moved the man away from the rest of his squad, which the team has just battled in an ambush. Reviewing their prisoners, the interrogator team pegged the man as a squad leader. Separating him from the rest of his troops enhances the shock of capture, which may allow the 525th to get information out of the man before he can get his story straight with the others in the squad. Down the road and behind a small bend, the man’s squad is put through the same process and asked similar questions by the interrogator’s squadmates.

“Who’s your commanding officer?” The questions keep coming.

The pockets are searched, and the questions delved into details. The man refuses to answer.

He's given some water and told he will be coming with the interrogators on the truck to the detainee holding facility, where he is going to be asked further questions.

Interrogator Olympics

The scene was the first moment of contact between opposing forces during five days of field exercises and competition among some of the Army’s most secretive soldiers: human intelligence collectors, or interrogators. As a week of August heat hit North Carolina, nearly 60 soldiers gathered in graffiti-covered cinder block buildings in a remote corner of Fort Bragg to practice interrogation techniques, a skill as old as war itself but rarely considered by even senior soldiers.

Senior enlisted noncommissioned officers observe from the back as the participating soldiers gather to hear instructions. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney.

For a week, human intelligence collectors — or “HUMINTers,” as they call themselves, members of the Army’s military occupational specialty 35M — interrogated notional detainees, compiled intelligence clues, and submitted reports in a first-of-its-kind competition dubbed the Interrogation Olympics.

The interrogators came from as far away as San Diego and Boston to participate. Once at Bragg, the HUMINTers stuck to their five-person teams, mostly soldiers with the MOS of 35M or 35F, the latter known as all source analysts or intelligence analysts. Competitors ranged from privates just out of the schoolhouse to staff sergeants and warrant officers with hundreds of hours of live interrogation experience.

Over the course of three days in August, Coffee or Die Magazine followed along as some of the Army’s most secretive soldiers put their skills to the test in a series of intelligence-collection field exercises, patrols, and interrogations.

Infil

For the first combat lane of the competition, Coffee or Die tagged along with the home team: five members of the 525th Expeditionary Military Intelligence Brigade, including four HUMINTers and one analyst.

A squad from the 525th Expeditionary Military Intelligence Brigade conducts a patrol in the backwoods of Fort Bragg, North Carolina, as a part of the Interrogation Olympics. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney.

They set out on a patrol that curved around dirt roads and through forest littered with pine cones, navigating to their objective. The weather was uncomfortable and sticky, and orb weaver spiderwebs lay in wait for the unsuspecting, sweaty faces of the HUMINTers.

As they approached a waypoint, the squad leader whispered instructions, and the squad took up security positions. The team needed to briefly reorient themselves, pausing for just enough time to glance at the map and discuss their path. They weren’t far from their designated location, and a minor adjustment down another small dirt road put them on the right route to the rally point.

In truth, tactical movements and fieldcraft are not the specialty of 35Ms, outside of those stationed in US Army Forces Command units, like Bragg’s 82nd Airborne. However, during some of the fiercest years of combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, when intelligence collection was often the primary goal of combat operations, HUMINTers accompanied direct-action units to carry out on-site interrogations and intelligence collection. And outside of direct action, HUMINTers often spend time in population centers, talking to people to gather information; it's the “human” element of HUMINT.

But the majority of a HUMINTer’s career is spent in detention facilities getting up close and personal with detainees.

The 525th squad didn’t know that an opposition force (made up of other 525th troops) was about to ambush them. These were the “Donovians,” the enemy of “Atropia,” the fictional country that the 525th soldiers were assisting for the competition’s scenario.

At the set moment, gunfire shattered the quiet backwoods as the Donovians attempted to surround and kill the US patrol. Luckily, the L-shaped ambush was more I-shaped, and the Donovian attack collapsed as the US squad responded.

HUMINTers from the 525th Expeditionary Military Intelligence Brigade — patrolling for the purposes of the competition — hit the deck as the sound of gunfire shatters the pleasant quietude of the North Carolina woods. A "Donovian" patrol ambushed the squad, firing on them from the left and right. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney.

Now the real exercise — and the contest — began.

With Donovian prisoners, the squad had to decide whether they wanted to take their prisoners back to base camp for interrogation or perform an interrogation right there in the field.

The shock of capture can be very effective, as an interrogator can use fear, uncertainty, and confusion to get information from a subject before he can mentally recover. But as the squad debated, a practical mistake was made: The team left a captured Donovian role-player momentarily alone with a weapon on the ground next to him, unsecured and out of view of the rest of the squad.

It's a fundamental mistake by the squad, and the observer-trainer accompanying the group can’t let it go: “For the purposes of this exercise, I want you all to watch this happen,” the warrant officer yells out — not upset, but teaching — as the interrogators and detainees alike snap out of the scenario to listen. “But in real life, that man might try to kill every single one of you if he didn’t simply run away first.” Usually, HUMINTers aren't the direct-action element alone on objective and almost always have some sort of security force along for the adventure, such as Rangers, infantry, or military police.

Opportunities for training and teaching moments permeated the competition — peer to peer, as well as more experienced HUMINTers imparting knowledge to the next generation. Regardless of the competitive nature of the exercise, opportunities to learn and grow were around every corner. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney.

With that, the squad collected the requisite “pocket litter ”— a map, a large paper that looked suspiciously like instructions for chemical weapons, lint, and some gum — and decided which Donovians to send to a holding area: a platoon sergeant and some senior soldiers.

The team soon arrived at a group of old Conex freight containers covered in years of graffiti, including “I love my government” and “fuck the cops.”

Inside the containers, the prisoners review their role-player packets of the secret answers and information before facing the interrogators. Each has been given a specific piece of information to withhold until the HUMINTers ask “the right questions,” using interrogation approaches that best “break” the detainee.

Col. David Violand speaks to the interrogators as they turn in for the evening. Violand has worked in several units and uses HUMINT as often as he can. Behind him stands Chief Warrant Officer 5 Jesssica Ohle, and Col. Bill Putnam observes, left. The entire exercise came about from friendly banter between the two colonels, who hoped to see who had the best troops. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney.

HUMINT

Col. David Violand is the commander of the 525th Expeditionary Military Intelligence Brigade. He thinks training exercises like the one on Bragg can not only improve HUMINTers' skills but also convince field commanders of their value to a front-line unit.

“There’s a big problem with interrogations: Commanders don’t want it until they need it," Violand told Coffee or Die. "Mostly because they don’t know what HUMINT does.”

The biggest victories of HUMINT are mostly unknown until they lead to a direct-action operation. Their role may never become public. But a minuteslong kinetic operation — a raid on a compound, the arrest of a wanted leader, the recovery of a hostage — can be a months- or yearslong project for the intel collectors behind it.

“This isn’t about training to standard; this is about training to stress levels. HUMINTers do jobs in dynamic conditions. I’ve never seen a combat unit want to let a HUMINTer go once they’ve seen the value of HUMINT.”

Much of the job is sitting across a table from someone who wants to kill you and convincing them of reasons they should betray everything they believe in and do as you ask. It’s not exactly an easy job, and it's an even tougher job to create training for.

“It’s labor intensive to train HUMINT,” Violand said.

The role players at the heart of any training must themselves be well-trained HUMINTers who can pretend to be soldiers, spies, innocents, or extremists.

Planning and preparation are crucial to an interrogation, as well as sitting down and discussing the intelligence collected after each one. Report-writing, preparing for the next session, and briefing all relevant information to teammates is an important part of the intelligence-gathering process. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney.

After basic training, HUMINTers are sent to Fort Huachuca, Arizona — a small, remote base just 65 miles from the Mexican border — where they train for close to 20 weeks. Half of the course is interrogations training, while the other half is on source operations, or working with informants.

For much of the last two decades, HUMINTers have trained for a “mature” combat environment, where the US has well-established bases and intelligence, like much of the war in Iraq and Afghanistan.

But training is now shifting toward “immature” environments, or “large-scale combat operations” (LSCO). Think Russia in Ukraine. Or China. In fast-moving future conflicts with large armies, intelligence troops will not have infrastructure — as they did in Iraq and Afghanistan — to rely on as large forces move front lines back and forth on a battle map.

"This isn't about training to standard; this is about training to stress levels. HUMINTers do jobs in dynamic conditions," Violand said of the competition. "I've never seen a combat unit want to let a HUMINTer go once they've seen the value of HUMINT."

And with larger armies comes more prisoners of war and more interrogations.

Readying for that is exactly what the Interrogation Olympics are for.

The interrogation process is delicate, and it can sometimes take weeks to get information from a detainee. In the shift from counterintelligence operations in a mature environment to a large-scale combat operations paradigm, the interrogation process doesn't change; the focus of the intelligence does. The interrogator no longer needs long-term addresses of high-value targets, but it needs to know numbers, the scale of the enemy's operation, and potential targets and vulnerabilities for immediate direct action. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney.

Interrogation

First, an interrogator must get a detainee to “break” — the key moment when they decide to cooperate. And all interrogators will tell you a fundamental truth of intelligence collection: Torture doesn’t work.

Interrogators know that abuses uncovered more than a decade ago still inform the public stereotypes of their jobs. Abuses chronicled in the Senate "Torture Report" regarding CIA “enhanced interrogation techniques” and reports on the Iraqi detention facility at Abu Ghraib found widespread mistreatment of detainees. Most abuses were perpetrated by troops not trained as interrogators or even intelligence soldiers.

But Chief Warrant Officer 5 Jesssica Ohle, the Army's senior interrogator, said the crimes uncovered in that era are today the building-block lessons at the heart of the intelligence community. The mistakes of the era were, she said, “a leadership failure that led to abuses by some very bad apples, not all of whom were interrogators, but all of whom should have known better.”

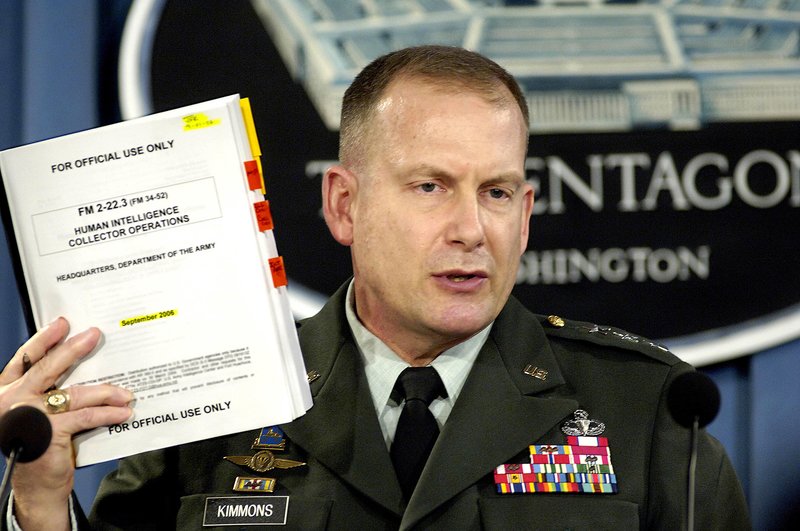

Interrogation, as taught and practiced by HUMINTers, is a fundamental game of establishing trust and, like an investigator at a crime scene, hunting for details. Every intelligence organization in the Department of Defense — including the CIA and the DIA — interrogates using the same methods as the Army, all outlined in Army Field Manual 22.2-3.

Lt. Gen. John Kimmons, US Army, holds up a copy of the Army Field Manual, FM 2-22.3, Human Intelligence Collector Operations, as he briefs reporters on the details of the manual in the Pentagon on Sept. 6, 2006. Department of Defense photo by Robert D. Ward.

“Who, what, when, where, why, how, what else,” and “what other,” coupled with “tell, explain,” and “describe,” is the language of the HUMINTer. Build rapport and drill down on the questions to get the details of every stray noun.

When a detainee has decided to cooperate, an exchange might go something like this:

Detainee: “There was some ammo in the truck.”

HUMINTer: “What kind of ammo?”

“Rifle ammo.” This is not actually good information, but the interrogator has the person talking. Now questions can be more specific.

“What was the caliber?”

“5.56 rounds.” The interrogator now knows that the enemy has Western-made small-arms weapons, but perhaps not heavier machine guns.

“How did it get in the truck?”

"We put it there."

Using greasepaint and old jungle battle dress uniforms, opposition forces identified themselves as "Donovians," the fictional enemy with intelligence to be gleaned. HUMINTers notionally captured several of these individuals, who are armed with packets of information to give the HUMINTers, if they feel convinced enough to do so. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney.

“Who is ‘we’?”

“Me, Marissa, and Jack.” Now the interrogator has names, and he knows that the local population, including women, may be assisting. The interrogator would likely follow up with separate interviews focused on each person the detainee mentioned.

“Where did you fuel up?” Now the detainee is talking about supply lines and logistics.

And on and on. It can be tedious and take hours, but the payoff is worth the time spent “in the booth.”

No interrogation is the same, but the rules never change: Focus on tiny details. ("How old are your maps?" "Did you buy those boots, or were they issued?") Never ask yes-or-no questions. Go into every interrogation with a wide knowledge of processes but also a vivid imagination for how small pieces of information fit together to make a larger picture.

After an interrogation is completed, reports are written for the next interrogator. A detainee’s story will be checked again, to see whether the details change in a second telling. In a real deployment, higher-level analysts combine the reports into daily INTSUMs, or intelligence summaries, for various echelon commanders and other intelligence agencies.

Military intelligence soldiers from the Army, Army Reserve, and Army National Guard listen to instruction and praise from the senior staff as they wait for the night to wind down. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney.

The Interrogation Olympics

The whole thing started with some friendly banter.

Col. Bill Putnam, the commander of the Army Reserve Interrogation Group, said he was “just talking smack” with Violand, the 525th’s commander, when the idea of a centralized competition for the whole HUMINT community came up. Putnam and Violand both agreed that it was important to have all three Army components train and compete together in a friendly game of “Let’s see who's the best: mine or yours.” At stake? Nothing but bragging rights.

They would put teams through a scenario used frequently at the National Training Center for the last 10 years: “Operation Atropian Freedom.”

There was the patrol destined to be ambushed at the rally point, as the 525th team had been. From there, the captured Donovian soldiers who attacked them would be interrogated to an 18-point list of “go, no-go” metrics.

Members of the winning squad stand proudly for their photograph. Because of calendar conflicts in their unit, the squad had less than two weeks to become familiar with each other before participating in the Interrogation Olympics. US Army photo by Staff Sgt. Jeremiah Meaney.

Final Briefs

After the interrogations were complete, each competitor team wrote their reports and prepared to brief their commander as a final culminating event.

Normally, a HUMINTer could plan on briefing a colonel or below on their field-level intel, but teams instead found the former commanding general of the Military Intelligence Readiness Command, Brig. Gen. Aida Borras, as their notional commander.

"This level of training and engagement is the best way to train soldiers. There is no better way," Borras told Coffee or Die.

The day after the final briefing, Violand proudly announced the 525th E-MIB as the reigning champions to beat next year.

The 525th’s team leader told Coffee or Die, “We definitely weren’t expecting it, but our team crushed it.” The sergeant said his five-man team — consisting of an analyst, three HUMINTers, and himself as the HUMINT team lead — only had about two weeks to coordinate between them. One had recently returned from an Iraq deployment, another was fresh from initial training, and another had been on a tasking since January. “Our analyst and our teamwork made [this] possible,” he said.

“I don’t think we’re going to do this in the middle of August again,” Ohle said with a laugh.

Read Next: Who Makes the Army’s ‘Best Squad’? Soldiers From 12 Commands Compete This Week at Fort Bragg

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.