‘Racing to Baghdad’: Three Veterans Recall Their Role in the Invasion of Iraq

Lance Corporal Chris Fleming didn’t know what day it was. His unit had been in Kuwait for days, maybe weeks, sitting in the desert and waiting to be told what to do.

“We finally got the word to deploy, and that was mid-March — I don’t know if it was the 17th, 19th, something like that,” Fleming said during a recent phone interview with Coffee or Die. “And we ended up loading up, and we started heading north to the border. And as we started rolling north and getting closer to it, the air assaults started.”

On March 19, 2003, the United States, along with allied forces from the United Kingdom, Australia, and Poland, invaded Iraq in an effort that is now remembered as the launch of Operation Iraqi Freedom. The objective was to unseat then-ruling dictator Saddam Hussein, who was believed to be in possession of or in the process of building weapons of mass destruction. Over the next several weeks, airfields were secured and Baghdad fell, ending Hussein’s 24-year rule. The invasion lasted until May 1, 2003, and marked the beginning of what has become a nearly two-decade conflict for the United States.

It was Fleming’s first deployment — the then-20-year-old maintenance manager and machine gunner had been in the U.S. Marine Corps for three years. His Christmas block leave ended prematurely after his unit was called back to Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, in December 2002. As part of the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines amphibious assault team, he boarded a ship in late January or early February 2003 for the month-long journey to Kuwait.

“We were at Camp Shoup, and at first it was, ‘All right, any day. Any day we’re going to go over,’” Fleming said, referring to the berm that separated Kuwait from Iraq. “Then it became, ‘All right, maybe another day. Maybe another day.’ Next thing you know it’s been weeks and weeks. And then we started thinking, ‘All right, well, what’s going to happen?’”

After they started moving north and the air assaults were taking place, Fleming remembered seeing missiles overhead and hearing bombs in the distance, but since he wasn’t part of the leadership group, he said he didn’t know what was going on. A few days later, his unit, a Marine Expeditionary Brigade (MEB) known as Task Force Tarawa, was sent into Nasiriyah to secure two bridges to the north and south.

In Nasiriyah, Fleming’s unit was facing “Republican Guards and Saddam Fedayeens, which are their better armies,” he said. “They’re not civilians — they’re highly trained, they’re well-nourished, they’re paid, and they’re bad dudes. […] So, we knew we were going to get into some stuff, we just didn’t know how bad it was going to be.”

Despite no tank support because they ran out of fuel, the MEB continued into the city and ultimately secured the bridges as part of the Battle of Nasiriyah. But it was hard-won.

“They fought us hard, and we lost a lot of vehicles,” Fleming said. “I want to say we lost nine or 10 of our vehicles, and we lost 20-something guys out of our MEB.”

His task force also recovered U.S. Army vehicles that had been abandoned when an Army unit was ambushed after accidentally moving through the city — a misstep made infamous by the capture, and later rescue, of Private First Class Jessica Lynch.

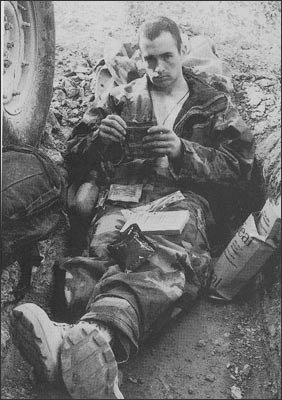

“We had a couple of intense nights,” Fleming said. “We slept in the dirt. We slept under our vehicles for a little bit of shelter. We never set up a camp, we never had downtime — it was constant moving, shifting focus […]. You didn’t have a minute to yourself.”

Also present at the Battle of Nasiriyah was 19-year-old Lance Corporal James Trombley. It was his first deployment as a U.S. Marine attached to the 1st Reconnaissance Battalion, which was the subject of the HBO miniseries “Generation Kill.”

“I think we were literally one of the first, like maybe three vehicles across the border into Iraq,” Trombley said in a recent phone interview with Coffee or Die. “When we staged right on the border for three or four days, that’s when they were shooting Scud missiles, and we could sit there at night and just see our air just blowing up the city north of us. It just looked like a big fireworks show for hours.”

His unit was in Nasiriyah for the first part of the battle and then pushed north to Baghdad and Kirkuk. They finally came back toward Kuwait in May and redeployed in June.

“It’s pretty well documented exactly where we went and the battles that we hit and things that we went through, too, through that series,” Trombley said of “Generation Kill.” “But more on a personal side, just the mentality of it — when we were staging in Kuwait, […] I think that kind of threw a lot of people off because they got to see some of the inside of how we act. […]

“A lot of them thought we were just crazy and out of our mind, and I was like, no — a lot of it was that we’ve got the mindset that we weren’t going to survive this,” he continued. “Like, we knew for 100 percent fact that we were going to die. So we just had a smile on our face and pushed forward and fought a war and just tried to do the best that we could until it was lights out.”

He said that most don’t, and can’t, understand that mentality — then added that he would do it again if he could.

“Of course, war is never a beautiful thing,” Trombley said, “I never hope for war. But we were there, and that’s what our mission was.”

While Fleming and Trombley made their way through Nasiriyah with their respective Marine Corps units, U.S. Air Force Staff Sergeant Ryan Shamrock was serving as a joint terminal attack controller (JTAC) providing close air support for the 75th Ranger Regiment for the planned airfield seizure of Baghdad International Airport.

Shamrock, who was 27 at the time, had been in the Air Force for seven years and was fresh off his second deployment to Afghanistan when the military started spinning up for Iraq.

“We started doing the planning for the airfield seizure of Baghdad International Airport, and we expected to lose a lot of troops,” Shamrock said during a recent phone interview with Coffee or Die. “We were planning for the worst-case scenario.”

Once in Iraq, and before implementing the plan to seize the airfield, the Ranger Regiment was tasked with establishing an entry point for troops that would come in behind them.

“So we moved to RR [staging base],” Shamrock said, “and about a week before the war actually kicked off [with] the air campaign, we ended up blowing a hole several miles wide between the Iraqi border and Saudi Arabia so that the ground invasion force could come through — it was actually about 18 miles wide.”

After that, they moved forward toward Baghdad to prepare for the airborne invasion of the airfield. The airfield mission ended up being cancelled, but the leadership wanted them in the fight, so Shamrock’s platoon was bumped over to perform combat search and rescue (CSR) and track high value targets (HVTs) who were fleeing north into the Sunni Triangle.

They had intelligence on one HVT in particular who was hiding out at an Iraqi theme park. “It was like going to Six Flags to look for a guy, but it was the cheap version of Six Flags,” Shamrock said, noting that it felt like something out of a video game. The park was a critical objective because of the power it generated for the surrounding area.

All told, Shamrock spent about six months in Iraq during the invasion, which also included participating in the Jessica Lynch rescue.

Shamrock had more combat experience going into the invasion than either Fleming or Trombley, noting that his previous deployments — including jumping into Afghanistan in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 — allowed him to face the invasion with a different perspective.

“Now, at that point, your third deployment, you’re really getting after it, you really start to settle in and come to grips with a few things,” Shamrock said. “And one of those things is your own mortality. […] Then I started to think about what kind of legacy would I be leaving if I was killed, or all the things that I wanted to achieve that I wasn’t yet able to achieve.”

Shortly after he redeployed, he separated from the Air Force.

While the actions and operations of the invasion of Iraq are seared into the minds of those who lived them, the memories of how they felt during those moments sit just as close to the surface.

As a young Marine, Fleming said that he did what he was told and didn’t ask questions, but now he has the time and resources to go back and look at things with a critical — and more complete — perspective.

“I still feel like we did what we were supposed to do,” Fleming said. “I’m actually still learning about it. Social media has helped a ton. It puts stories together — because at the beginning, all there was was one book — and it would help me see the bigger picture of what was actually going on.”

Shamrock echoed that sentiment, saying that at the time he didn’t recognize the impact of the work he was doing. “You know it’s part of history and that you’re doing something pretty cool, but you don’t think of the impact that it will have,” he said.

Trombley, who served two additional tours in Iraq after the invasion, said that the experience changed his perspective and how he approaches life on a daily basis.

“I look at running water differently than most people do,” he said. “I mean, that first invasion we went there, it was 50-some days or more that we couldn’t even shower. Our [food] supply train got hit, and we were down to one MRE a day for like a month. […] It definitely changes your perspective on life — I mean, things aren’t as bad as most people try to make them out to be.”

As far as whether the invasion was a success, Trombley said that it probably wasn’t in the sense that they didn’t find the WMDs, but the everyday Iraqi citizens loved that the Americans were there. Trombley added that on his subsequent tours they helped build infrastructure like schools, reunite families, and establish farming, but much of that has been lost.

“They’ve been fighting in that region for as long as we can remember,” he said. “It was pretty naive of us, I think, to go in there and think that we were going to take over one dictator and then there was going to be a thriving metropolis” like it used to be.

Katie McCarthy is the managing editor for Coffee or Die Magazine. Her career in journalism began at the Columbus (Georgia) Ledger-Enquirer in 2008, where she learned to navigate the newsroom as a features reporter, copy editor, page designer, and online producer; prior to joining Coffee or Die, she worked for Outdoor Sportsman Group as an editor for Guns & Ammo magazine and their Special Interest Publications division. Katie currently lives in Indiana with her husband and two daughters.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.