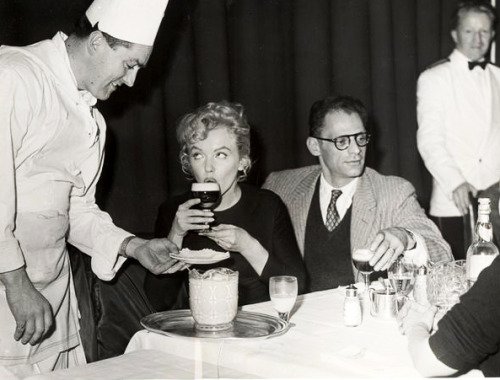

Photo courtesy of the Foynes Flying Boat & Maritime Museum.

Ireland was a neutral country during World War II. Even though its military wasn’t involved in armed conflict during the war, an estimated 12,000 Irish soldiers volunteered to serve under the British and fight alongside those troops. Neutral countries also provided opportunities; for example, Stockholm in Sweden infamously became known as the “City of Spies” because of frequent espionage activity. In Ireland’s case, the flying boat base at Foynes on the country’s west coast was a major port that also served as one of the largest civilian airports in Europe at that time. Military personnel, civilians, and even royalty traveled aboard luxury trans-Atlantic seaplanes and landed on the Shannon River’s watery runway.

It wasn’t unusual for passengers to be traveling in and out of Foynes using fake names and fake passports. All military personnel were required to wear civilian attire, but those rules were later relaxed. “Who are we neutral against?” became a running joke among the employees. The flying boats at Foynes later earned fame for transporting refugees escaping from war-torn Europe. These refugees would board a seaplane in neutral Lisbon, Portugal, fly to Foynes, Ireland, and purchase a ticket for America where they would begin a new life. Since the layovers were particularly long due to operational reasons, mechanical delays, or weather, Foynes modified its amenities to make travelers from all over the world feel welcome.

When Brendan O’Regan was appointed catering comptroller in 1943, he opened a restaurant and coffee shop in the Foynes terminal building. O’Regan added Irish decor and employed a well-educated staff to give the impression of strong Irish ideals. He hired a chef named Joe Sheridan to run the kitchen. In the winter of 1943, a pilot on a flight to New York flew through several hours of bad weather and decided to return to Foynes to wait for the weather to pass. The control center received a Morse code message to prepare for their arrival. Sheridan was asked to make something warm for the cold and unsettled passengers.

He prepared black coffee with an added twist. One traveler thanked Sheridan for his delicious cup of joe and questioned whether he had used Brazilian coffee. “No, it was Irish coffee!” Sheridan exclaimed. He had added a dash of Irish whiskey to warm them up.

Although Foynes’ flying boat base shut down in 1945, Sheridan and his staff brought the Irish coffee recipe to what would become Shannon Airport in Rineanna. Stan Delaplane, a travel writer from the San Francisco Chronicle, passed through the airport in 1951 and tasted Irish coffee for the first time. Delaplane had won the Pulitzer Prize for reporting in 1942, but he’s perhaps most famous for bringing the Irish coffee to America.

When he returned to San Francisco, he told his friend and owner of the Buena Vista Café, Jack Koeppler, about the new drink. They couldn’t at first replicate the same Irish coffee that Sheridan had produced. After further research, they recruited the mayor of San Francisco, who happened to also be a prominent dairy farmer, to address their problem: They couldn’t get the cream to float. The mayor came up with a solution for the perfect froth. And in 1952, Koeppler offered Sheridan a job in the US, which he emigrated from Ireland to accept. On average, the Buena Vista Café produces 2,000 Irish coffees per day.

The Irish coffee didn’t leave Ireland entirely. The original recipe can still be enjoyed where it was developed at the Irish Coffee Lounge at the Foynes Flying Boat Museum. The original five-step recipe is as follows: Preheat a coffee mug or glass with boiling water, then empty it. Add 1 teaspoon of brown sugar and a “good measure of Irish whiskey,” then fill the mug or glass with strong black coffee, leaving a third to half an inch of space at the brim. Gently pour lightly whipped cream over the back of a spoon so it floats. It’s important not to stir after adding the cream because the best coffee and whiskey flavor is tasted through the cream.

Now that you know the history of the Irish coffee, you know it’s not just for St. Patrick’s Day. These simple and delicious ingredients will warm you up any time of the year, as it has for decades for countless others.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.