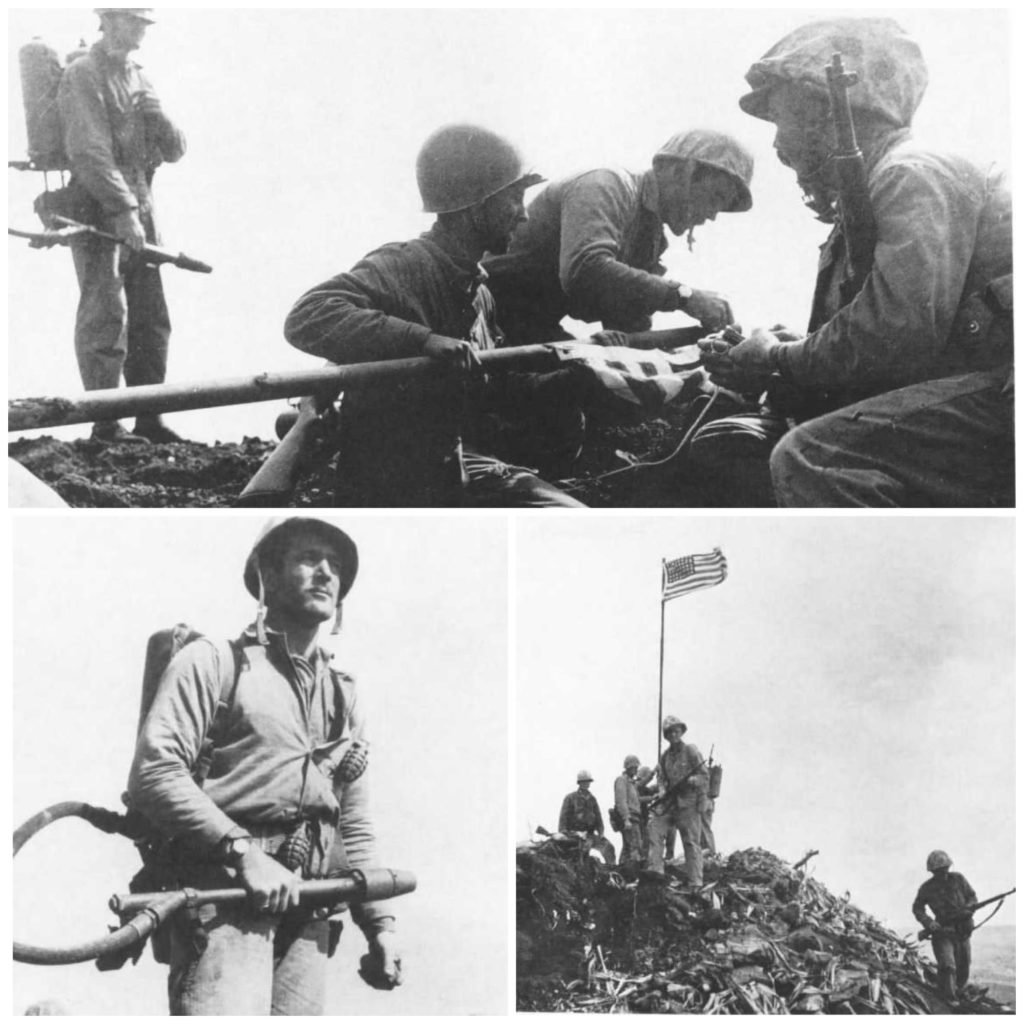

The famous picture taken by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal actually captured the second flag-raising event of the day. A US flag was first raised atop Suribachi soon after it was captured early in the morning. National Archives photo.

H-Hour was set for 9AM as U.S. Marines and U.S. Navy corpsman prepared to launch an amphibious landing on the morning of Feb. 19, 1945. At sunrise, before the assault began, more than 450 ships bombarded the island in what became the largest naval bombardment in history. The island of Iwo Jima was a strategic location for both the Japanese and the Americans. The Japanese had three airfields where their long range fighter aircraft, the Mitsubishi A6M “Zero,” could intercept long-range B-29 Superfortresses as they prepared to bomb targets over Japan. They also flew over Saipan, where American forces frequented. The Americans saw Iwo Jima as the perfect staging ground for allied escort aircraft for these types of protection operations.

Some 21,000 Japanese soldiers prepared to prevent this by defending it to the very last man. Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the commander of all Japanese forces on Iwo Jima, even went so far as to declare, “Above all we shall dedicate ourselves and our entire strength to the defense of the islands.”

U.S. Marines had difficulty during the landing because of the “black sands of Iwo Jima,” referring to volcanic ash that limited their mobility. They were immediately pinned down by walls of gunfire coming from the top of Mount Suribachi, a 550-foot extinct volcano. Adding to the difficult terrain and against heavily fortified Japanese positions were 642 blockhouses, pill boxes, and other gun positions that were spotted from aerial and submarine surveillance prior to the invasion. The Japanese had a year to prepare 16 miles of hand-dug tunnels where they lived and fought from inside the mountain.

These four lesser-known stories from the iconic Battle of Iwo Jima highlight some of the brutality that resulted in more than 26,000 American casualties.

Marine War Photographer Bill Genaust

The iconic photo of raising the flag on top of Mount Suribachi was taken on the fourth day of intensive fighting. Before Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal snapped the black-and-white photo with his camera, another photographer named Sergeant Louis R. Lowery from the Marine Corps magazine Leatherneck had a harrowing experience. At 10:30AM on Feb. 23, 1945, Lowery photographed the first raising of the flag on Iwo Jima, but a Japanese soldier lobbed a hand grenade and knocked Lowery off the mountain. He fell 50 feet but miraculously survived, although most of his camera equipment was destroyed.

At noon, Rosenthal and Sergeant William (Bill) Genaust stood next to each other as they captured history. Genaust used his 16mm moving picture with color film to capture the video of the raising of the second flag. The small victory indicated progress, but the U.S. military still had the northern part of the island to defeat, a battle that consisted of 36 days of bloody and brutal fighting. Six days later, Genaust thought a sophisticated cave complex had been cleared by the Marines at Hill 362A and used either a flashlight or his camera to advance deeper inside. Japanese soldiers fired at the light and killed him instantly. He was first deemed missing in action (MIA) after the entrance was destroyed via dynamite and bulldozers had sealed it.

Later, a seven-person government team was sent to Iwo Jima to recover his remains, but they were determined unrecoverable in 2007. In 1995, a bronze plaque was placed to honor his memory.

It’s worth noting that before Genaust went to Iwo Jima, he served as a combat photographer in Saipan. On July 9, 1944, a warm Sunday morning, Genaust put away his camera and grabbed a rifle. A tank notified him and fellow combat photographer Howard McClue that they were desperate for infantryman.

As they pressed on to find the Japanese soldiers, their tank ran over a landmine and was rendered useless. They continued to pursue the enemy, attacking and killing 12 Japanese soldiers who were holed up in houses. As more infantry reinforcements showed up, they returned to the base to turn in their film. They were ambushed by 15 Japanese soldiers from 200 yards away.

Genaust later wrote to McClue’s wife: “We hit the deck and sought what cover we could — Howard on my right and McNally on my left. We knocked down several of them on their way down the slope and the rest of them sought shelter and firing positions behind some rocks and 50 or 75 yards in front of us. I was so busy for a while that I didn’t notice the withdrawal of either Howard or McNally. McNally had run out of ammunition and Howard had gone to get help for us. In about 30 or 45 minutes, I saw Howard coming in on the right, leading a group of Marines he had picked up further back.”

Genaust was nominated for the Navy Cross but was denied because cameramen couldn’t receive awards for combat.

Carnage on Hill 382

What Private First Class Douglas T. Jacobson accomplished during the desperate fight to capture Hill 382, the highest point of elevation on the northern island, is almost hard to believe. The sector he and the Fourth Marine Division assaulted was so violent that it was declared the “Meat Grinder.”

The 19-year-old Jacobson seized the opportunity to grab a bazooka, hoist it over his shoulder, and run to collect a satchel full of explosives while bullets and shrapnel whizzed by his head. He shouldered the bazooka and took out a 20mm anti-aircraft gun and its crew. In his next consecutive shots, he single-handedly destroyed two machine-gun nests, two fortified blockhouses, seven rifle emplacements, and a tank.

After the dust settled, he wiped out 16 enemy fortifications and killed 75 Japanese soldiers determined to kill him. “I don’t know how I did it,” he said. “I had one thing on my mind, and it was getting off that hill.” President Harry Truman awarded him the Medal of Honor, but Jacobson continued to serve. He totaled 25 years of service and reached the rank of major. He even saw action in Korea and flew aboard helicopters during Vietnam.

In 1985, on the 40th anniversary of Iwo Jima — where nearly 7,000 U.S. Marines and Navy corpsman were killed — he spoke to the audience. “Those were the days when men were men and proud of it,” he said. ”They never asked if this island was needed or if the war was just. When they were called to do their duty, they stood up and were counted.”

Marine Higgins Boats

For the Marines who stormed Iwo Jima, the experience of fighting in hand-to-hand combat was traumatic. However, shuttling the Marines to and from shore was equally harrowing. Referring to Higgins boats during the “island hopping” campaigns, General Dwight D. Eisenhower later said, “That boat won us the war.”

James D. “Dud” Morris was a part of the fifth wave to hit Yellow Beach during the invasion of Iwo Jima. “One thing I will always remember from that first beach landing were all of the Marines lying on the beaches. Before we landed, I thought they were there firing at the Japanese,” he said. “When we hit the beach, I realized they were all dead or wounded. It was a terrible sight to see. By late that afternoon they stopped us from going in so they could clear the debris and the bodies that had accumulated on the beach. We had no relief crew for our boat. We worked, slept and ate on that boat for 10 days straight. We would go to the ships we were off-loading men or supplies and ask for food and water, which they always provided.”

When they weren’t offloading fresh Marines to take the fight to the Japanese, they were loading wounded Marines to transport to hospital ships. “The hospital ships had pontoon barges alongside the ship. We would off-load the wounded onto the barge and they decided who to take up for treatment first,” Morris said. “Some of the boys were in really bad shape. The third and fourth day we delivered the Third Marine Division to Iwo. They were supposed to be held in reserve for the Okinawa but they were needed now on Iwo because the first day we had almost 2,500 casualties.”

Milton Brown Alligood was part of a Higgins boat crew that was responsible for dropping the hatch to lower the steel bow ramp to land Marines on Red Beach during the initial assault. The brutality of war was a wake-up call for all that were there. “We went back to the beach with another load of Marines. On our return trip to the ship we had a load of wounded Marines on stretchers,” Alligood said. “I was holding this wounded Marine in my arms. He said, ‘Light me a cigarette, will you?’ He took a couple of puffs on the cigarette and died in my arms. That can turn an 18-year-old into an old man in a hurry.”

Marines and Navy corpsmen weren’t the only ones to ride in the historic naval vessels, however. Although Marine K9 handlers were more prevalent in Guam and the other islands, the 7th War Dog platoon saw action in Iwo Jima. These dogs were lifted by their handlers into the Higgins boats and scampered across the island alongside their human companions. One photo shows Private Rez Hester taking a nap in a sandy foxhole while Butch, his Doberman Pinscher, stands watch. These war dogs provided an extra capability in detecting camouflaged or hidden Japanese soldiers. Edmund Adamski, a veteran of the invasion of Guam, commented, “The hair on the back of his neck would stand up. That told me there was something out in front of us. He absolutely saved my life many times on patrol.”

Marines and Flamethrowers

During the “island hopping” campaigns, Marines were notorious for their use of flamethrowers and napalm. Napalm was considered a heroic battlefield innovation during World War II but became demonized during the Vietnam War. After the war, U.S. General Curtis Lemay wrote that in 1945, napalm “scorched and boiled and baked to death more people in Tokyo on that night of March 9-10 than went up in vapor at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined.”

Napalm wasn’t used solely as an incendiary dropped from airplanes. It was also used in flamethrowers because it had 10 times the duration of other gelled fuels and three times the range. “We could have never taken the island without the flamethrower,” said Bill Henderson, a Marine who fought on Iwo Jima, speaking to the weapon’s effectiveness. “It saved lives because it did not require men to go into caves, which were all booby trapped and promised certain death to all who entered.”

Although they were incredibly effective in combat, flamethrowers were a huge target to the Japanese and had a 92 percent casualty rate. It was later reported that the average lifespan for a flamethrower operator was a mere four minutes. One of the most notable flamethrower operators to serve during World War II was Medal of Honor recipient Corporal Herschel “Woody” Williams. He single-handedly wiped out several Japanese pillbox positions during a four-hour battle. He frequently returned to American lines to swap his empty flamethrower packs for full ones and even braved a banzai attack — fire versus bayonets.

“It was like fighting ghosts,” he said. “One minute the enemy was attacking and being killed, then they would disappear, including their dead. They were going underground into 16 miles of tunnels we didn’t know existed.”

Corporal Charles W. Lindberg, who took part in the first raising of the Iwo Jima flag on top of Mount Suribachi, was a flamethrower operator who was awarded the Silver Star. He was part of the first wave of 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines who stormed within 10 to 15 meters of Japanese soldiers who engaged him with hand grenades, explosive charges, and small arms fire. Lindberg exposed himself to take out several concrete-enforced caves that contained as many as 70 enemy combatants.

In order to prevent the 92 percent casualty rate from rising, flame tanks added protection and duration to the operators. The Marines from 5th Tank Battalion expended 10,000 gallons of napalm per day, and a later report on the effectiveness of the flame tank stated it was “the one weapon that caused the Japs [sic] to leave their caves and rock crevices and run.”

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.