Jackie Robinson Faced a Court-Martial for Refusing To Move on a Bus

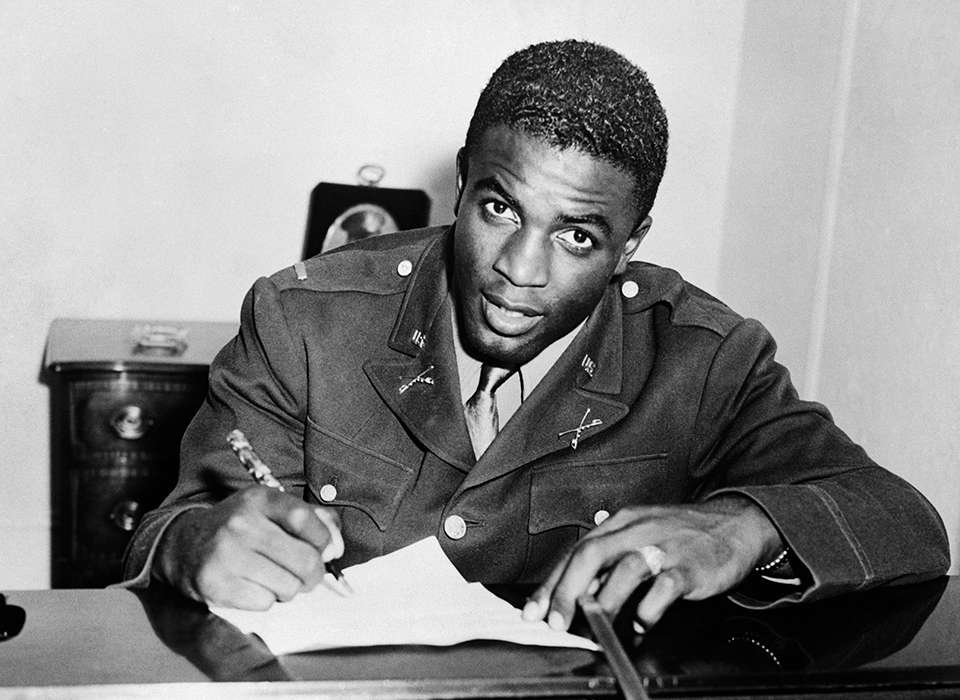

Jackie Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947, but before his hall-of-fame career, his quest for equal rights resulted in his court-martial in the US Army. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Long before Jack “Jackie” Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier, he faced a court-martial in the Army for refusing to move to the back of a bus.

“I was in two wars, one against the foreign enemy, the other against prejudice at home,” Robinson said, according to the Society for American Baseball Research.

Robinson, a four-sport athlete at UCLA, was in Hawaii in December 1941, playing semipro football in Honolulu. He left the island on Dec. 5, just two days before the attack on Pearl Harbor that would drag the US into World War II. He was drafted in April as a 23-year-old private, reporting to Fort Riley, Kansas.

Though the Army was almost entirely segregated, Robinson directed his soldiers to host a variety show for Black troops called the Brown Bomber War Bond Rally. World-famous boxing champion Joe Louis, otherwise known as the “Brown Bomber,” was also stationed at Fort Riley, and all together, the event raised more than $500,000.

“His arrival at Fort Riley brought much-needed power to the black soldiers and gave Jack an opportunity to form an alliance and work with his longtime hero,” Rachel Robinson, his wife, wrote in Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait.

After Robinson’s application to officer candidate school had been denied three times, he was finally accepted and took an assignment as a morale officer in charge of the segregated portion of the post exchange, or PX. The PX had only six or seven seats assigned to Black soldiers. When soldiers returned from the theater or other activities, his men were often left standing, despite numerous other open seats. He informed his soldiers he’d take action immediately.

“My statement was met with scorn,” he recounted in his book I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography of Jackie Robinson. “I realized that not only did these soldiers feel nothing could be done, but they did not believe any black officer would have the guts to protest.”

He phoned the provost marshal from his desk at company headquarters, and after identifying himself as the morale officer of his outfit, he informed the commander about his issue. He explained how Black and white soldiers were to fight this war together, but the major said that efforts to change the seating situation were hopeless.

“Finally, taking for granted that I was white, he said, ‘Lieutenant, let me put it to you this way. How would you like to have your wife sitting next to a nigger.’”

Robinson erupted into a rage, and the clerks at the headquarters were frozen in disbelief that a Black officer had defended himself. A warrant officer advised Robinson to share with a colonel how Robinson had been provoked into a tirade. The colonel wrote a strongly worded letter to correct the conditions at the PX as well as a request for disciplinary action against the provost marshal for his racial attitude.

“He proved to me that when people in authority take a stand, good can come out of it,” Robinson wrote.

Robinson’s interactions at Fort Riley when interfering with white soldiers were often contentious; however, his experience at Fort Hood, Texas, received national attention.

He was assigned as a platoon leader to the 761st Tank Battalion — the famous “Black Panthers” who later stormed across Europe. Robinson had a bad ankle at the time and agreed with a colonel to get a waiver from a nearby hospital before going overseas. On July 6, 1944, he took a bus to the hospital and, spotting the wife of one of his fellow lieutenants, sat down beside her.

“The driver glanced into his rear-view mirror and saw what he thought was a white woman talking with a black second lieutenant,” Robinson wrote. “He became visibly upset, stopped the bus, and came back to order me to move to the rear. I didn’t even stop talking; didn’t even look at him; I was aware of the fact that recently Joe Louis and Ray Robinson had refused to move to the backs of buses in the South.”

In the wake of the incidents with the two famous athletes, the Army had issued an order barring racial discrimination on any vehicle operating on an Army post. Robinson knew the rules were on his side when he stood his ground.

The bus driver ultimately flagged down military police officers.

“I was naïve about the elaborate lengths to which racists in the Armed Forces would go to put a vocal black man in his place,” Robinson wrote.

After the incident, Robinson was charged with insubordination and disrespect, and he faced a jury with just one Black soldier versus eight who were white (though one of the white officers had gone to UCLA). But fellow Black officers penned open letters to prominent Black newspapers to increase public pressure. In the end, Robinson was acquitted.

#BlackHistoryMonth#DYK in 1947, Jackie Robinson became the first African American player in @MLB.

Robinson was a well-rounded athlete, served in the #USArmy, and was active in the Civil Rights Movement. pic.twitter.com/U6zofdTT60

— U.S. Army (@USArmy) February 1, 2022

Robinson left the Army in 1944 and soon after began his hall-of-fame career in baseball. He played 10 major league seasons with the Brooklyn Dodgers and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962. His jersey number, 42, was eventually retired across the entire league.

Read Next:

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.