James Armistead Lafayette: The American Revolution Double Agent Who Helped Washington Defeat the British

Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold and 1,600 of his Loyalist troops had successfully besieged and captured Richmond, the capital city of Virginia, in January 1781. The American turncoat set up a headquarters in Portsmouth and requested that British soldiers under his command bring enslaved Black Americans to serve in exchange for their freedom.

In walked James Armistead with a secret.

Arnold asked what he could do for the enslaved man standing before him, and Armistead explained he could use his services. He was born into slavery, he told him, and he knew the landmarks and how to navigate at night. He understood shortcuts and routes that only a local Virginian would know when they were safe to use.

Arnold accepted him but had him doing menial tasks at first, such as pouring cups of tea and taking care of uniforms — the tasks performed by so many other slaves who left their masters to join the British cause. The British officers at the encampment often spoke freely about military and intelligence operations because in their eyes their hired help, whose service was a means to secure their freedom, was invisible. And the penalty for slaves sharing British military discourse from behind closed doors was a death sentence.

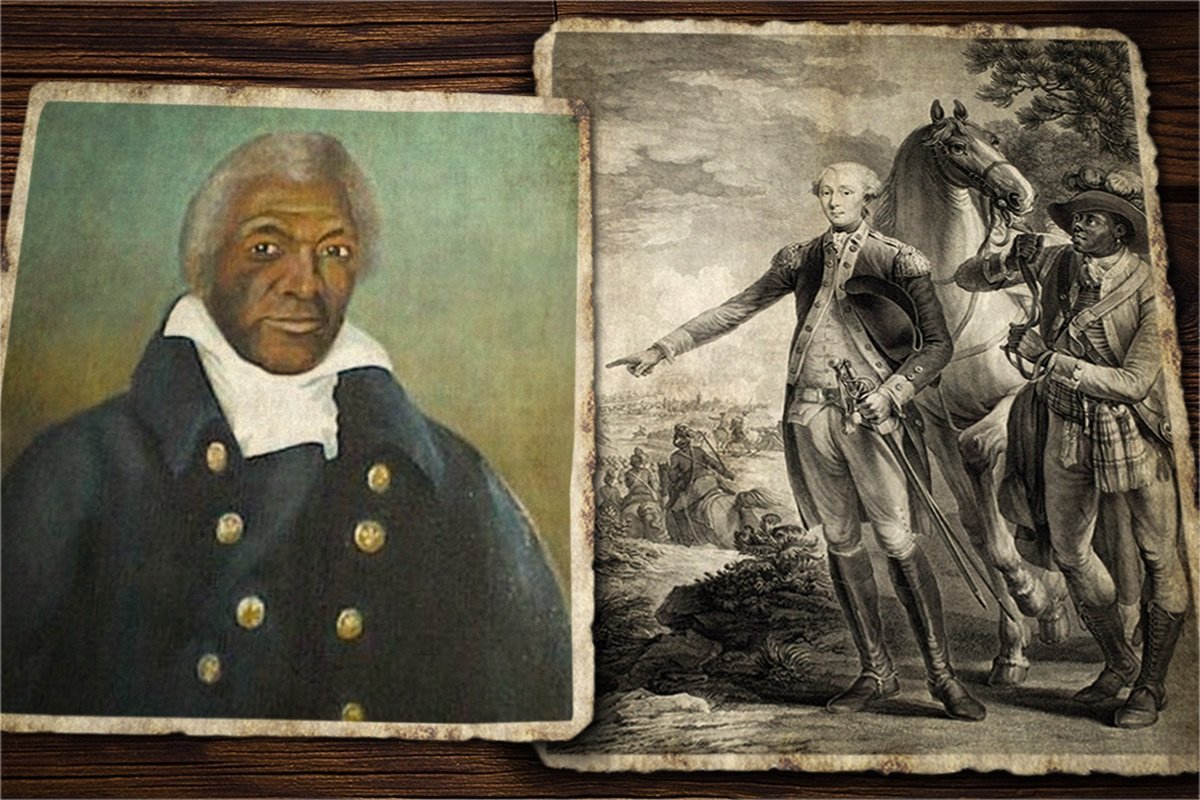

This lack of awareness exposed Arnold’s weakness, which the Marquis de Lafayette, a French military officer and commander of American troops, sought to exploit. Armistead hadn’t escaped from his owner after all; in fact, he had asked William Armistead for permission to leave and become a spy for Gen. Lafayette. He knew how to read and write, important skills for analyzing important documents. His secret was his art of deception, which he employed to infiltrate the inner circles of British high command, leveraging their prejudice as a shield.

His work as a servant under British Army Gen. Charles Cornwallis advanced into a role as a spy. Armistead, now a double agent, had the freedom to walk between British lines without trouble and had gained access to the most discreet meetings. He’d scribble handwritten cables in secret to be handed off to other spies and delivered to Lafayette. His reports to Cornwallis were inaccurate, full of false information provided by Lafayette to misdirect the British.

Armistead’s most critical contribution as a double agent was his intelligence report at the end of the summer of 1781. The report detailed the movements of Cornwallis and nearly 10,000 British troops to Yorktown. The tip gave Gen. George Washington the actionable intelligence to stun the British, ultimately defeating Cornwallis and forcing his surrender on Oct. 19, 1781.

A hero of the American Revolution, Armistead didn’t receive a hero’s welcome. When the war ended in 1783 he discovered his work of espionage did not fall under Virginia’s rule of law. The Emancipation Act of 1783 states that enslaved men who “have faithfully served agreeable to the terms of their enlistment, and have thereby of course contributed towards the establishment of American liberty and independence, should enjoy the blessings of freedom as a reward for their toils and labours” — but spies were the loophole.

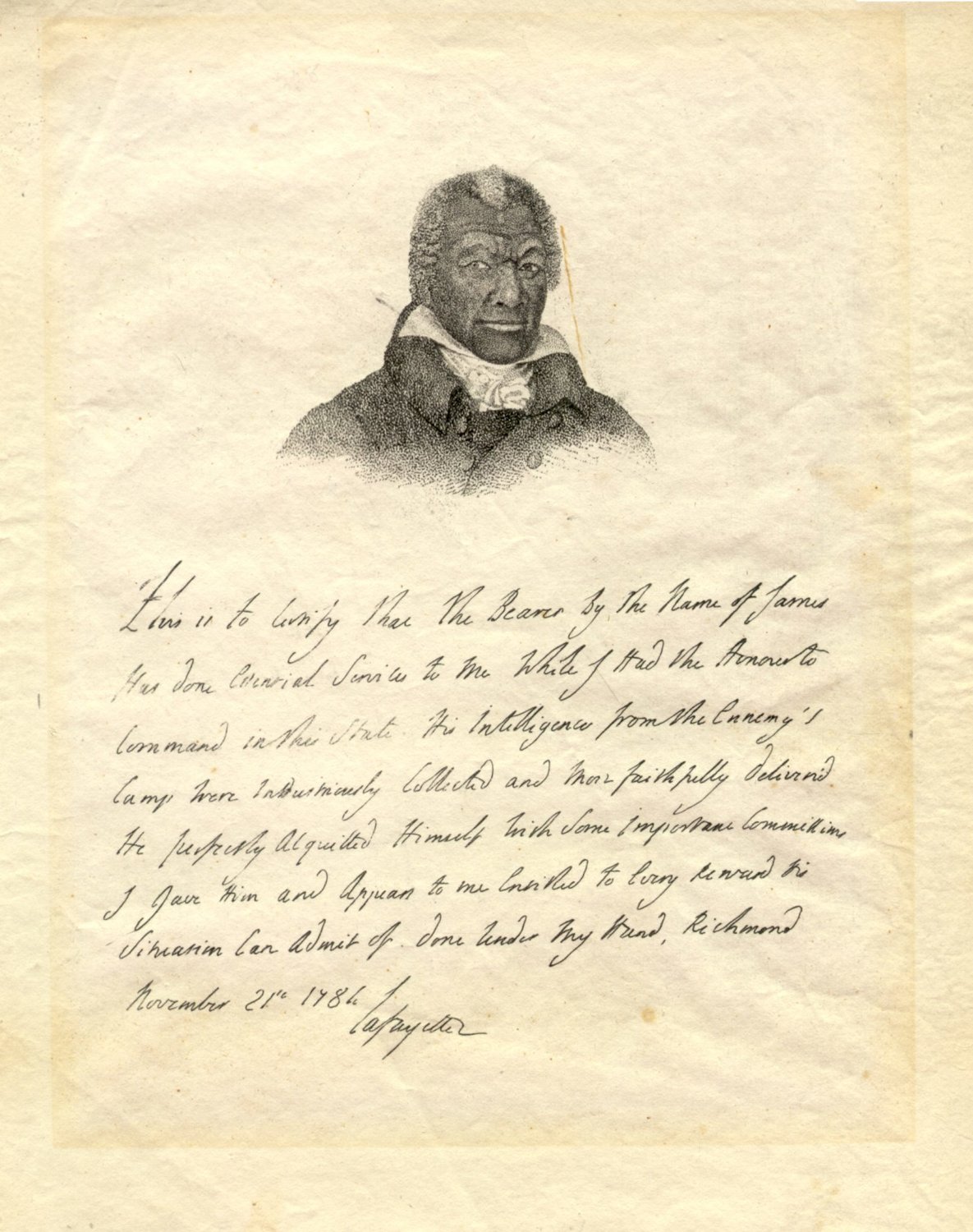

Armistead’s attempts at a petition were ignored — at least until Lafayette’s personal testimony brought awareness of his wartime service:

“This is to certify that the bearer by the name of James has done essential services to me while I had the honour to command in this state. His intelligences from the enemy’s camp were industriously collected and faithfully delivered. He perfectly acquitted himself with some important commissions I gave him and appears to me entitled to every reward his situation can admit of. Done under my hand, Richmond, November 21st, 1784. Lafayette.”

Armistead gained his freedom in 1786 after the Virginia General Assembly recognized his service as a spy and paid his owner. In appreciation of his commander’s support, he adopted his commander’s last name, becoming James Armistead Lafayette. Not much else is known about his time as a free man, except that when the Marquis de Lafayette returned for his grand tour of America in 1824, the friends reunited and embraced.

James Armistead Lafayette is one of the American Revolution’s unsung heroes, a Black American slave and spy who risked being hanged for treason for the price of freedom.

Read Next: Knowlton’s Rangers: America’s 1st Organized Intelligence Unit

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.