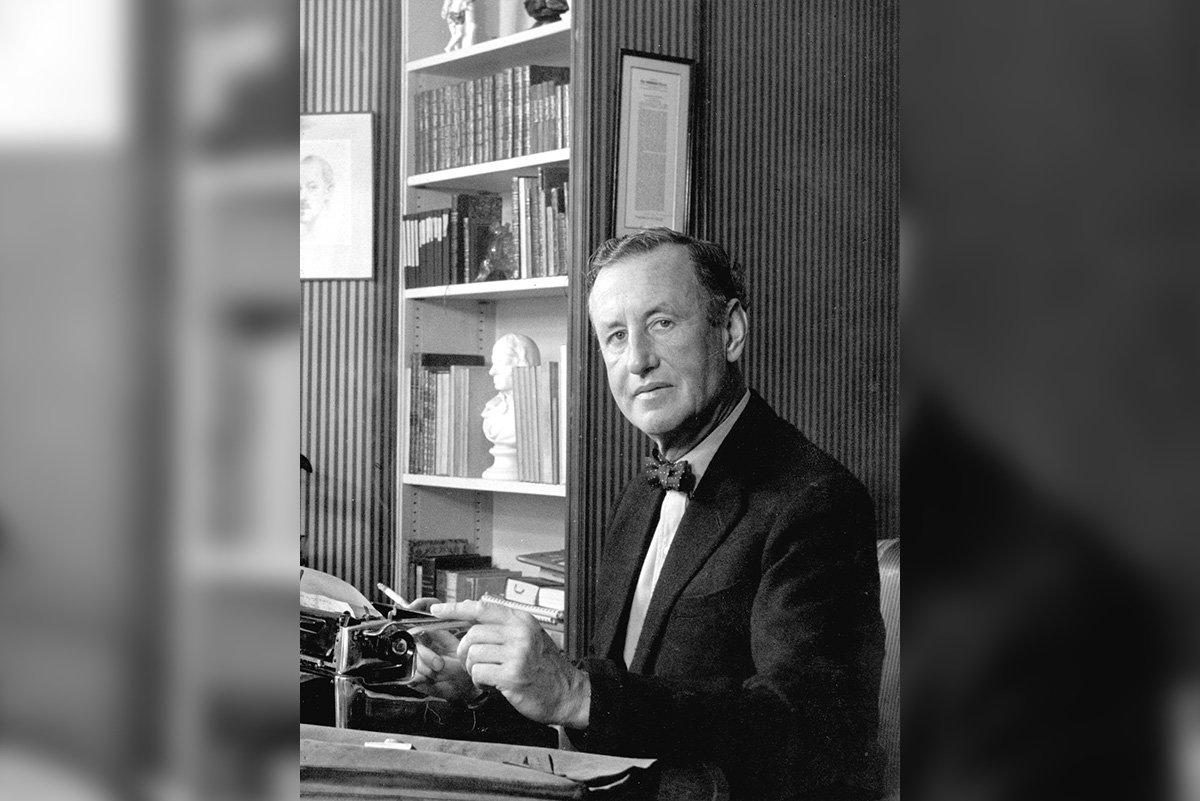

Who is the real man behind the myth? Photo courtesy of Facebook.

“The name’s Bond. James Bond.”

Sitting on a tropical beach in the early 1950s, smoking cigarettes and drunkenly watching birds, Ian Fleming — English author of Casino Royale — wove his love of Jamaica into his novels, using the tropical paradise as a haven for his fictional secret agent James Bond. He wrote most of his books there, preferring to sit at his typewriter with the Caribbean breeze blowing through his open-air home. He loved watching birds and letting them fly in and out of his open windows.

Fleming identified them with the help of a book, Birds of the West Indies, by none other than the real James Bond, not a spy but a Philadelphia ornithologist. Fleming took the author’s name for his fictional hero, finding it to be a “blunt, ethnic-neutral, macho name.” Fleming’s Bond became the main character of 12 novels and 25 films starring six different actors and worth a whopping $16 billion in about 60 years of profits.

The real Bond, who authored Fleming’s “bird Bible,” shared an uncanny parallel past with both the fictional character and Fleming. Though Bond was eight years older than Fleming, like Fleming he experienced the death of a parent, spent time at an elite British boarding school (Harrow), and attempted to enter the financial sector before ultimately settling on his final vocation. Their lives diverged significantly, however, as Fleming committed his life to intelligence work and Bond to his birds.

Bond graduated from Cambridge, explored the Amazon and Caribbean jungles, and wrote more than 100 scientific papers and books. Mary Bond, his wife, recalled phone calls in the middle of the night from strange women asking to speak with Bond, apparently unable to distinguish her husband from the fictional secret agent.

In his book, A Glorious Enterprise: The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia and the Making of American Science, Robert M. Peck — the curator of art and artifacts and senior fellow at the Academy of Natural Sciences — described his friend Bond as “a brilliant and sophisticated, but unassuming gentleman who devoted his life to studying the birds of the West Indies. The last thing he expected — or wanted — was to become a universal symbol of sex, glamour, and intrigue.”

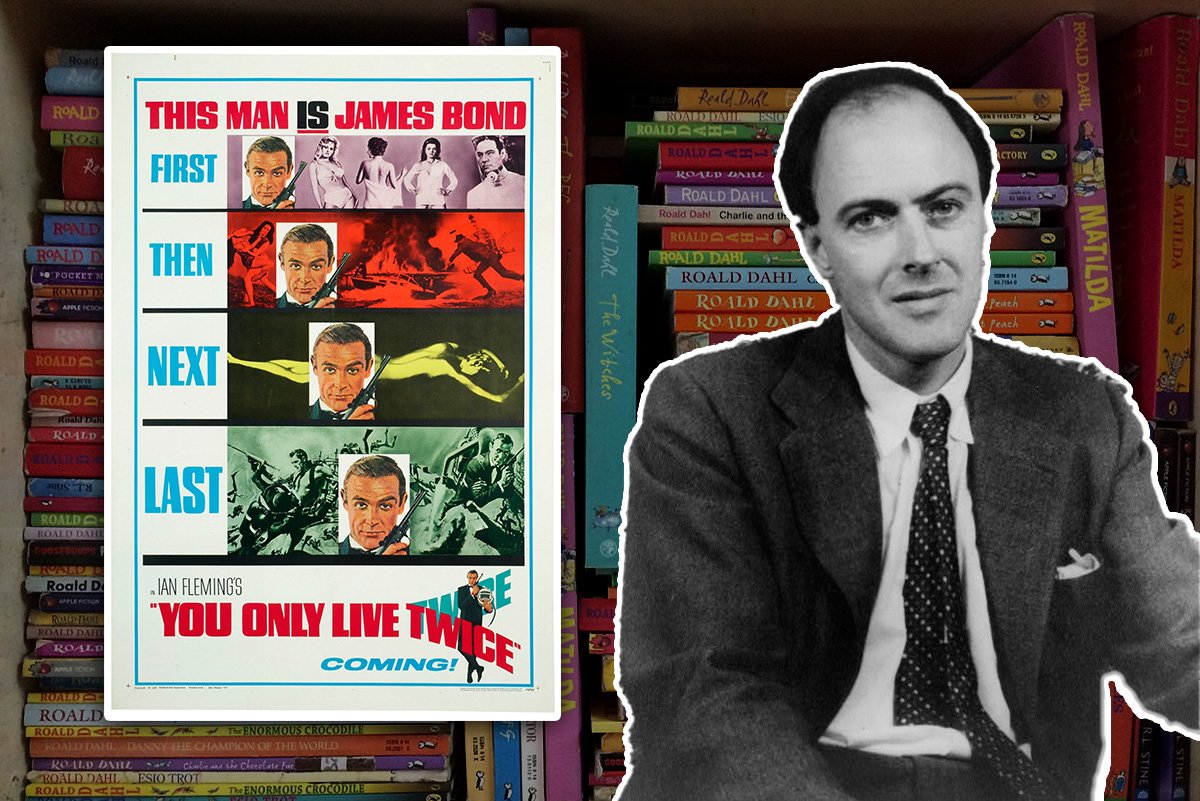

Taking no inspiration from the skilled ornithologist besides his name, Fleming borrowed from from his war experiences and those of his contemporaries, Roald Dahl, Dusko Popov, and Johann Jebsen, to create his fictional spy.

Dahl, another spy-turned-author, wrote in an entirely different genre, preferring to dabble in children’s fiction. Dahl wrote the popular works Matilda, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and James and the Giant Peach. During his days as a Royal Air Force fighter pilot and British spy, his exploits were, as The Trunchbull would say, “much too good for children.”

As his weapon of choice, Dahl often used his “golden gun” in the bedroom — not unlike the fictional Bond does in his (s)exploits — to obtain useful information.

Dahl’s superiors in England sent the 6-foot-6 RAF pilot, in a dashing uniform no less, to Washington, DC, hoping to subtly influence politicians to advocate for US military support in World War II by way of boots on the ground. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, Dahl had no trouble finding socialites, journalists, and congresswomen — and congressmen’s wives — to schmooze in the nighttime.

Dahl’s friend Antoinette Marsh Haskell, an heiress and socialite, described him as “arrogant with his women,” adding, “I think he slept with everybody on the east and west coasts that had more than $50,000 a year.”

Fleming’s other major influences were Popov — a Serbian spy — and his friend Jebsen. Popov grew up wealthy, with yachts, private schools, and an excellent family reputation. He went to school for law and, after receiving his degree, moved to Germany and became friends with Jebsen, a German intelligence agent. Like Popov, Jebsen liked fast cars and faster women.

As Nazism overtook Germany, Popov frequently argued with Nazis in pubs and public spaces. In 1937, Popov found himself in the custody of the Gestapo. Jebsen called Popov’s father, who, as a wealthy man with influence, was able to secure Popov’s release only eight days later.

Popov and Jebsen both later agreed to work with the British and spy as double agents. In Operation Midas, Popov took $50,000 given to him by the Germans, who believed he was establishing a spy ring in London, and was to deliver it to MI6. Fleming met up with Popov to supervise him until he got the money to MI6. A series of events followed in which Fleming helplessly watched as Popov played a $50,000 game of chicken with a Lithuanian baccarat player in a Portuguese casino. Sound familiar? It’s an element of the Casino Royale plot in which Bond bankrupts a Russian baccarat player.

Jebsen didn’t live through the war. He was likely killed at the hands of the Abwehr following a stay at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany. Popov survived the war, but he died in 1981 the same way Fleming had — of heart failure caused by excessive drinking and smoking. The fictional Bond miraculously avoided both fates.

Read Next:

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.