How Nirvana Rocker-Turned-Special Forces Veteran Jason Everman Rediscovered the Music

Jason Everman served as an Army Ranger in the 1990s, then reenlisted in 2000 in the Special Operations Forces, deploying to both Iraq and Afghanistan. Photo courtesy of Jason Everman.

A man sits at the window-facing counter of a dive bar in Bremerton, Washington, plotting how to make the best use of his time. A handwritten list in front of him reveals he needs screws from the hardware store, oil, coolant, reef lines, and a flagpole from the marine supply store. An American flag-garnished toothpick left over from Independence Day skewers a lemon wedge resting at the bottom of his glass alongside dying ice cubes. Vodka tonic. From the well. Chunky silver rings adorn his fingers, and a multitude of bracelets scrape the counter as he inks a star next to the words “Confirm OITF.”

Nothing about the man at the counter suggests he was kicked out of two of the world’s most famous grunge bands before becoming an elite member of the US Special Forces. That’s exactly how Jason Everman likes it.

When he’s done with his drink, he packs up his list, and we walk toward the marina where Everman moors his sailboat, one of the places he feels most at home these days. It’s a pleasant 64 degrees with the promise of late afternoon sun — a promise that gets pushed back an hour every time he checks the forecast.

We board Gita — Sanskrit for “song” — and Everman attempts to tie down a halyard flapping in the breeze. Then we descend to the cabin to talk.

Everman’s life began on a remote Alaskan island, but his parents separated early on, so he calls the small Washington town of Poulsbo home. His mother struggled with addiction, and Everman went through a phase of acting out, culminating with the time he and a friend blew up a toilet with an M-80 explosive in junior high.

“I don’t know whose idea that was.” When pressed, he adds, “It might have been mine.”

Everman found his “gateway drug” into the world of rock ’n’ roll around third grade when he saved up his birthday money and bought his first record, Alive! by Kiss. He always wanted to be a drummer, but drums were too expensive. After the M-80 incident, his grandmother sent him to a therapist who had some guitars displayed around the office. Everman gave one a couple of strums and was hooked. He learned the root notes, then mastered the tricky barre chords.

“All rock ’n’ roll is barre chords,” he says with a laugh. He had the key to the kingdom.

He joined multiple punk bands in high school and even played live shows in Seattle.

“Music was the only thing I cared about in high school,” he says. “Playing music and getting away.”

Everman’s childhood friend Chad Channing met a guitarist and a bassist from Olympia, Washington, and started drumming for them. When frontman Kurt Cobain wanted to add another guitarist in early 1989, Channing had just the guy in mind.

“The thing about Nirvana, at least the time I played with them, is they never rehearsed,” Everman remembers. He learned all the songs by listening to their demo tape and played with them for the first time at an Evergreen State College dorm party. “That was kind of my audition.”

Everman, who had followed the band through its early lineup and name changes, couldn’t believe his luck. It was the kind of break a musician gets once, if they’re lucky.

“Playing in bands, it was always just for fun,” he says. “It was never the option of making a living doing it.”

One of the then-21-year-old’s first tasks with the band was to pay the $606 they owed for recording the album Bleach. Even then, that amount of money — more than a grand in today’s dollars — meant nothing to him. He’d spent summers working on his biological father’s boat in Alaska since his junior year of high school.

“I would work a fishing season and make, like, $35,000 with no expenses,” he recalls. “I didn’t have a house. I didn’t have a family. It was all gravy.”

In thanks for the money, Everman was named on the back of the album as a guitarist, even though he didn’t play a note. He also appears on the front cover, headbanging with the band.

In the summer of ’89, he took off on his first tour with Nirvana, folding his tall frame into a van and seeing the United States for the first time. He’d backpacked in Europe twice but hadn’t experienced much of his home country.

“We would just drive to the show. Sometimes you’d soundcheck; sometimes you wouldn’t. Sometimes there’d be people; sometimes there wouldn’t. Sometimes you’d get paid; sometimes you wouldn’t. But it was part of the adventure,” he says.

Usually, they’d crash on the floor of someone’s house, typically someone in another band. On the tour itinerary, Everman kept a list of phone numbers for people they could hit up and ask for a place to sleep.

But the tour ended on a bad note. Everman didn’t notice it happening, but the other band members felt he was moody, reserved. They drove back to Washington, and Everman was out. He never got paid back for Bleach, which has since sold around 2 million copies. In an interview the next year, Cobain chalked the separation up to a difference in style.

“[Everman] liked the heavier, grungier stuff, and we had a few songs that we hadn’t recorded that he really liked and we didn’t want to do ’em, mainly I didn’t want to do them ’cause I was such a dictator,” he said.

Everman concurs. “I get it, like, it’s Kurt’s band. Obviously he’s a brilliant songwriter. So he totally made the right move,” he says in hindsight.

A dejected Everman started planning a trekking trip in Nepal to get his mind off things. Then he got a call from Soundgarden guitarist Kim Thayil. Founding bassist Hiro Yamamoto had quit.

Everman auditioned and got in. It was a dream come true. While Everman had been a fan of Nirvana, he loved Soundgarden. He remained cautiously optimistic, fearing it was too good to last. A week after he joined the band, they went to Los Angeles, played some shows, and shot a video with a director, crew, soundstage, and budget. A whirlwind European tour followed, and this time he rode in an actual bus, slept in hotels, and had roadies to load the gear. All the stuff that sucked about touring was removed from the equation.

That’s when the stress started to set in. Everman was about 10 years younger than the other guys, and he was inexperienced. He felt overwhelmed, and it showed.

“So I got kicked out of the band,” he says matter-of-factly. It hadn’t bothered him so much with Nirvana, but with Soundgarden it put him in “a bit of a tailspin.” After a couple of dark months, he packed up and moved to New York, thinking the best course of action was to remove himself geographically. He got a shitty apartment in Manhattan’s East Village and worked in a warehouse.

Music lured him back. He joined Mind Funk and moved with them to San Francisco where a Navy SEAL veteran directed one of their music videos. The prospect of joining the military had increasingly occupied Everman’s thoughts. His stepdad and other family members had served in the Vietnam era and World War II, but at that stage in his life he wasn’t close to his family and didn’t run across many veterans in the “wacky world of rock ’n’ roll.” The chance encounter with the SEAL was the catalyst he needed to take his life in a radically different direction.

Everman took out his nose ring, buzzed his long auburn curls, and ditched the hallucinogens. Then he headed to Fort Benning, Georgia, as a 25-year-old blank slate, hoping to fade into the crowd and earn his place without drawing attention to himself.

His drill sergeants had a different idea. One day in early April 1994, they stormed into the barracks screaming and throwing trash cans and generally smoking the hell out of the recruits. Everman cursed the Georgia humidity as he did endless pushups and sweat pooled on the floor beneath him. One of the screaming drill sergeants paused in front of Everman, locking eyes for a moment.

“‘The lead singer for Nirvana killed himself yesterday,’” Everman recalls him saying. Everman’s secret was out. Before long, everyone was calling him “rock star.”

But Everman excelled as a soldier. He completed the Ranger Indoctrination Program, which basically just exists “to make people quit.”

Grueling road marches, timed runs, combat-swimming tests, and other torturous physical trials weeded out recruits. Anyone who says they didn’t think about quitting is lying, he says. “But that’s the watershed. You think about it, but you don’t do it.”

After completing the Rangers’ selection process, Everman wound up back in Washington, assigned to 2nd Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment at Fort Lewis. They sent him to Jungle Operations Training in Panama, and he reveled in the triple canopy rainforest. It was peacetime — post-Desert Storm, post-Somalia — so his enlistment was mostly training. Some of his senior and junior noncommissioned officers had served in the 1989 invasion of Panama and craved the next conflict. Everyone was bored, waiting for the moment “some 48-hour war” would pop up and provide some excitement.

“I can’t speak for everyone in the military, but I wanted to go to war,” Everman says.

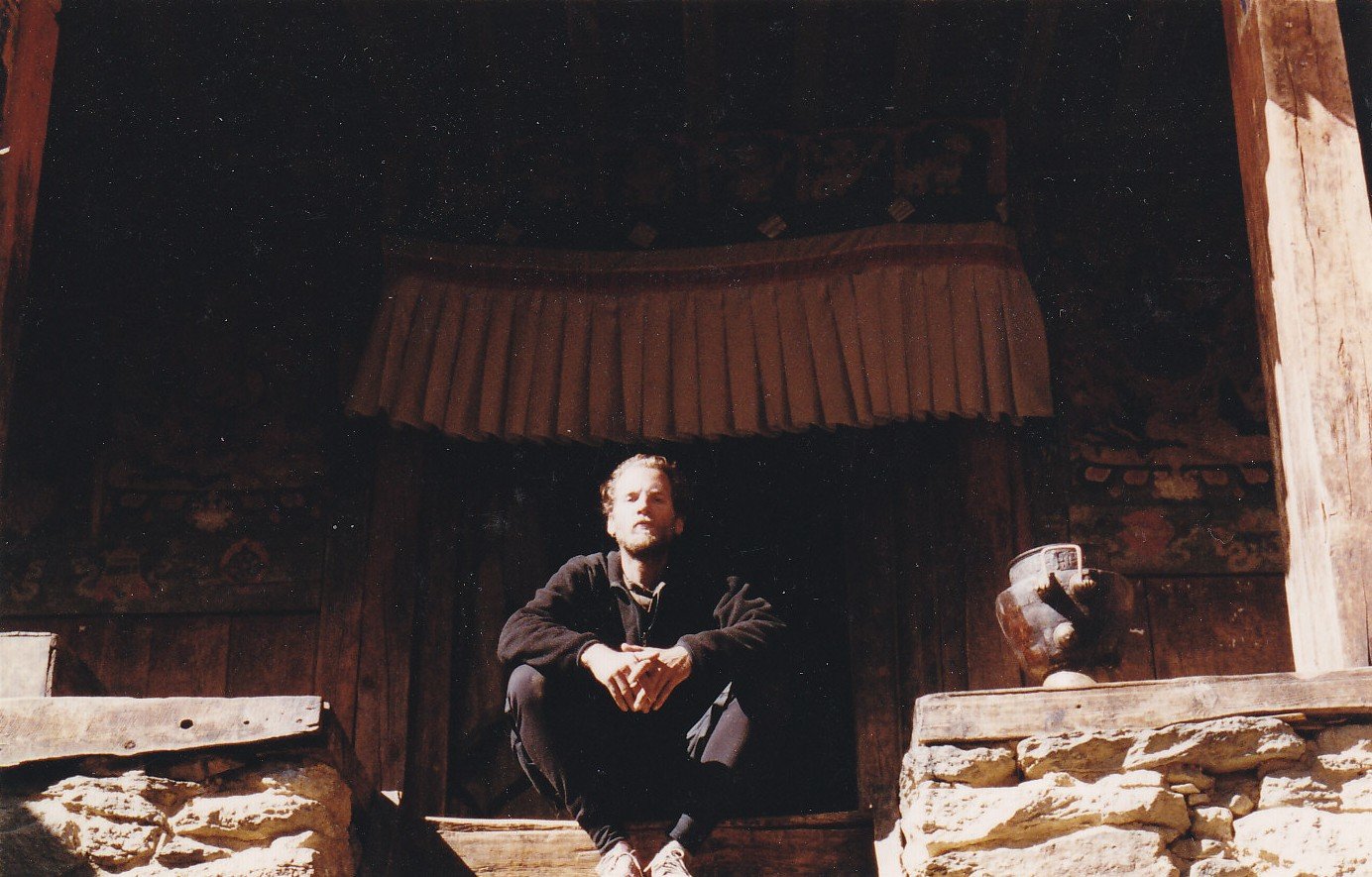

He never got his chance with the Rangers. In 1998, Everman finished his four-year commitment with the Army, trekked through the Himalayas, and joined a Buddhist monastery, which he says had a lot in common structurally with a military unit. The rinpoche — reincarnated spiritual leader — is the battalion commander. The young monks are the privates, tasked with menial chores like chopping firewood and washing dishes in between meditating and studying. Everman liked the military parallels and the discipline, but he never had any of the starry-eyed epiphanies Westerners often expect from the experience. His fondest memories were listening to bootleg Metallica cassettes with the other young monks.

When he got back to Washington later that year he went through a “mini existential crisis,” possibly the worst three months of his life. His epic travels were over, and he couldn’t find consistent work. His romantic relationship at the time was falling apart. His mom drank herself to death.

That dark time in his life was another turning point. He decided to enroll at Olympic College. In high school, he’d taken his SATs in the college’s rotunda as an excuse to hang out with his friends. He dropped acid before the test, believing there was no fucking way was he ever going to college. More than a decade later, he rolled up to the same rotunda for one of his first classes.

“So there I am, not on acid this time, eating my words,” he reflects. Everman realized he loved college and promptly earned an associate’s degree.

The sense that he had unfinished business in the Army nagged at him, so he returned, set on making Special Forces. He took a trip to New York City and toured the World Trade Center during the long weekend between Robin Sage, the four-week exercise all Special Forces candidates must pass, and language school. He flew back to Fort Bragg and started language school the next day. Televisions covered one wall of the student commons, and Everman watched on CNN as a plane crashed into the World Trade Center.

“This is a game-changer,” he remembers thinking. The room turned electric. It was the moment Everman and so many other soldiers had spent years waiting for. They were going to war.

Everman finished language school and his company headed to Kuwait, training during the buildup. He was impatient, restless, and stuck in the ’90s mind-set — he was worried the conflict would end fast and he’d miss all the action.

His company deployed to Iraq attached to the 3rd Infantry Division, and Everman finally got an up-close look at the awesome power of the American military.

“Special operations is sexy. It’s cool. High adventure, whatever,” he says. “But American military might is in our conventional forces. It’s unbeatable.”

He saw Abrams tanks engage Iraqi tanks. “Bam bam bam, tanks blown up everywhere,” he says. “It’s crazy.”

Afghanistan, by contrast, had a much lower intensity in the early days of the war.

“Lots of boring missions,” he says. “But then once in a while things would go sideways and you’d have some crazy gunfight and then go on to another string of boring stuff. It was an entirely different war.”

But the geographic beauty and confluence of cultures in Afghanistan fascinated Everman. There’s a famous photo of him standing in the snowy mountains of the Kunar Valley, snowshoes on his feet and a rifle held across his chest.

“It’s like Yosemite. It’s beautiful. If they ever stabilize that place, they could have ecotourism,” he says. “Rafting down the Kunar, heli-skiing, the same kind of trekking I did in the Himalayas — you could do in Afghanistan if it were stable.”

After having spent so long in the Army during peacetime, seeing fighting up close moved combat from an abstract concept to something real. Tangible. Bloody. Life-altering.

“It was probably the most profound experience of my life,” he says.

“Without sounding too pretentious, kind of like, understanding the human condition,” he continues. “It takes an event as extreme as war that simultaneously brings out both the worst and the best in people, which seems like a logical contradiction. You’re literally willing to kill someone, actively killing people, but at the same time that’s when someone jumps on a grenade to save their friends. So it’s on the one hand merciless and on the other hand kind of just like selfless love.”

Finally, Everman found what he had been searching for.

He left Afghanistan and the Special Forces in 2006 and applied to Columbia University as a joke. No way would he get into an Ivy League school. But with the help of a letter of recommendation from Gen. Stanley McChrystal, his former battalion commander, he was accepted.

He earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy, then a master’s degree in history from Norwich University a few years later with the goal of being a professor. That’s still in the realm of possibility, but so are a million other things.

Everman is constantly on the go. He recently tried to count how many countries he’s been to and thinks it’s close to 100. He loves Argentina because that’s where he was exposed to the concept of assado, which, he explains, is both a verb and a noun. The technique of cooking and the event of people coming together and enjoying the food.

“Being in Argentina, I realized I went through most of my adult life not really appreciating food,” he says. “Actually learning how to enjoy good food was like this huge epiphany for me that happened probably way too late in life. Now I love good food. I love teaching myself to cook, the creative process.”

That new passion led to what Everman calls Salon Assado. He invites a bunch of people to his house and cooks an Argentine-style meal for them. Picture a lamb, roasting over an open fire for nine hours, just starting to approach doneness by the time the first guests arrive. Rabbit, chicken, and vegetables roasting on a pot over a pit. He’s hosted four so far, each with around 30 or so people from all phases of his life. His old buddy Chad Channing even came to the last one.

He still plays guitar in the rock band Silence & Light, which is composed entirely of special operations veterans.

When Army Ranger veteran and guitarist Brad Thomas decided he wanted to start a band and donate the proceeds to charitable organizations helping vets, he immediately thought of Everman. Although they had both served in the Ranger regiment at the same time in the ’90s, Thomas and Everman didn’t cross paths during their time in the Army. Of course, Thomas still heard about him.

“Everybody knew I was a guitar player. So as soon as Jason showed up, the word spread like wildfire,” Thomas remembers. “‘Hey, did you hear about this guy in 2nd Ranger Battalion that played in Nirvana?’”

Thomas says he didn’t hear the dramatic details about Everman’s exit from Nirvana and Soundgarden until after a mutual friend introduced the pair and Thomas coaxed him into joining Silence & Light. When Thomas stumbled across old interviews with Cobain and the rest of the band characterizing Everman as moody, he realized they just hadn’t understood his bandmate.

“I think they were expecting something from him that just wasn’t him,” Thomas tells me over the phone a couple of weeks after I met with Everman. “He’s not like this cheery, bubbly, over-the-top personality. He’s very pensive, thoughtful — deep. I think they were looking for this surface-level party guy.”

Thomas remembers recording their first album in early 2019 with the help of Grammy-winning producer Josh Gudwin. The quintet, normally scattered across the country, gathered at Stagg Street Studios in Van Nuys, California, but Everman could only be there the first few days. The band live tracked everything the first day, meaning they played together and set the tempo before everyone recorded their individual parts. Then the drummer went to record his part, but it took three days. Thomas could see Everman getting stressed.

“He was exactly in that place where I feel like he was with Nirvana,” Thomas says. “He was very quiet, and everybody was kind of worried that he wasn’t happy with the recordings. We were just trying to feel out if there was a problem.”

Finally, it came to a head.

“‘I just want to get my stuff done because I’ve got to go, and I want to make sure that when I come back in however many months, my shit’s on the album,’” Thomas remembers Everman saying. Thomas realized right away that Everman’s frustration was rooted in the past, not aimed at his current bandmates.

“It was an emotional moment because it was kind of like him confronting his demons,” Thomas remembers. “Ever since then, everything has been absolutely perfect in terms of relationship, how we write, how we communicate. Everything.”

For Everman, Silence & Light offers a heavy style reminiscent of the grunge era, plus all the best aspects of being in a band.

“Everyone has a SOF background and similar experiences, but also this love of rock,” he says. “The motivation is just the love of the music, and there’s really nothing other than that. It’s basically like back when I was a teenager bashing out songs in my friend’s bedroom.”

It’s the joy of creating without the pressure of needing to get signed or go on a huge tour, something Everman said is probably not in the band’s future.

“Which is fine with me. I’ve checked that box. I don’t need to ride in a van at 53 and load my own gear into the venue,” he says.

Plus, he’s too busy with other endeavors.

He spends much of his time these days on his boat. When we meet, Everman is fixing it up so he can sail to a pop-up restaurant event called Outstanding in the Field. It’s coming to the San Juan Islands, and Everman plans to anchor up next to the farm hosting the dinner.

He writes in fits and starts and thinks about composing a collection of short stories when the time is right. A sort of literary nonfiction autobiographical project in the style of Kerouac or Hemingway.

And there’s still the allure of drumming.

“Have you ever seen that documentary Tim’s Vermeer?” he asks.

I’ve heard of it. It follows an engineer as he sets out to replicate a painting by 17-century Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer.

“Slayer’s original drummer, Dave Lombardo, was awesome,” he says. “I’d like to do kind of a parallel thing, call it Jason’s Lombardo and learn how to play a Slayer song just like Dave Lombardo does.”

The belief that time matters more than money has always guided Everman’s decisions — whether he realized it or not. If he had to define himself philosophically, he says he’s a physicalist.

“We’re organisms that exist in this real world, this physical world. Like, this is real,” he says and knocks on the table between us in Gita’s cabin. “This is a table. We’re people. The world’s out there. We interact and do stuff. All of that’s real, and there’s nothing beyond that. When my body dies, that’s it. My existence as this organism is done. So that’s why it’s important to make the most of your time here.”

When we finish our interview, he walks me back up the dock to the marina gate, pausing to admire the bright-orange jellyfish clustering around the boats and pilings.

“Lion’s mane,” he says, then warns me that they pack a powerful sting. A few steps later he points out a glossy black cormorant perched across the water on a different finger of the dock. He is completely at ease in this environment.

Earlier in the day I had asked if it’s weird being a mere 20-minute drive from the tiny town where he grew up, after all these years and his angsty teenage dream of getting as far away as possible. He said no because he has a lot of friends from his childhood and newer friends visit often. The Puget Sound draws an eclectic mix of people; it’s not uncommon to meet a gun-toting, Second Amendment-heralding granola hippie. A rock star/Green Beret/sailor doesn’t stand out in the slightest.

Walking to my car, I realize Everman’s answer makes sense. He’s educated and well traveled, humble and unpretentious, quick to point out that he had professors at Olympic College who were just as good as ones at Columbia. Words poured out when we discussed his favorite authors — Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Carver, Geoff Dyer — but slowed when I asked about his life. If I hadn’t known who Everman was before talking to him, I suspect I would have walked away three hours later not knowing he’d played for two of the biggest bands in grunge history.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2021 edition of Coffee or Die’s print magazine as “Seeking Salvation.”

Read Next:

Hannah Ray Lambert is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die who previously covered everything from murder trials to high school trap shooting teams. She spent several months getting tear gassed during the 2020-2021 civil unrest in Portland, Oregon. When she’s not working, Hannah enjoys hiking, reading, and talking about authors and books on her podcast Between Lewis and Lovecraft.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.