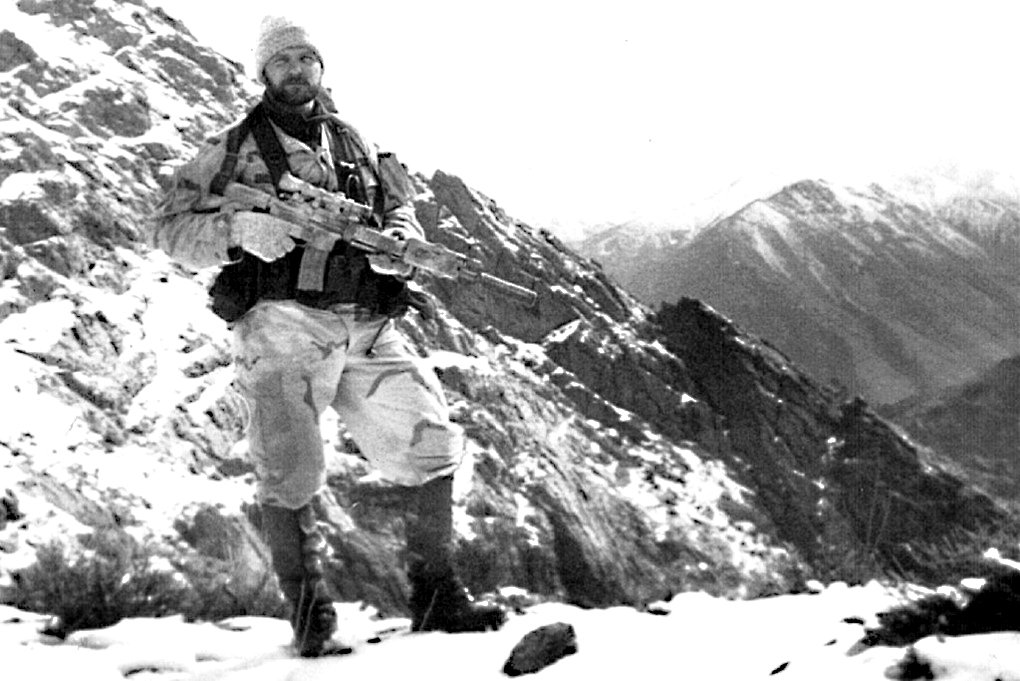

Air Force Tech. Sgt. John A. Chapman was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. Chapman, a combat controller, was the 19th Airman awarded the Medal of Honor since the Department of the Air Force was established in 1947. He was the first Airman recognized with the medal for heroic actions occurring after the Vietnam War. U.S. Air Force courtesy photo.

This essay by Dan Shilling originally appeared in Volume 7, Issue 3 of the Air Commando Journal and has been edited for length.

John Chapman died violently. Given his chosen profession as an Air Force Combat Controller and his choice of assignment to the 24th Special Tactics Squadron, the prospect of that outcome was always possible. However, it’s not his death and the devastating wounds he experienced in his last hour of life that turned his mountaintop isolation into heroic self-sacrifice, but rather what he did in the 71 minutes after his SEAL team left him, believing he was dead, until the moment he was struck by the bullet that ended his life.

When his actions were fully recognized, he was awarded the first Medal of Honor to an Air Force member in 47 years.

John’s decisions and actions were the result of thousands of hours of training and years of expertise understood by few individuals in or out of the military. The training may have determined his capabilities and martial accomplishments, but that is not what made John Chapman the man he was. The decisions and twist of fate that delivered John to that frozen and fateful summit where he saved the lives of 23 comrades were both humbler and more complex. From the earliest years of his childhood, John showed a commitment to defending others.

John was in kindergarten in Windsor Locks, Connecticut when he first chose to stand for someone who couldn’t defend themselves. It was everyone’s first day at Southwest Elementry and Billy Brooks and was the new kid in town. So, when he said the wrong thing to a classmate, she punched him in the stomach, dropping the new kid to his knees. John saw the fray from nearby and stepped in front of Billy, facing down the assailant and holding up his hands as if to say, “Hold on, here.” John Chapman was five years old. The friendship forged that day followed the two boys into adulthood.

By 1979, John established himself as a young man possessed by an innate ability to tune into the feelings of others that transcended the attitudes of the times and ran counter the instincts of most teenagers. Some of his unconditional friendships in high school weren’t looked upon with approval by other members of John’s “jock squad,” the student-athletes and cool kids. As a standout athlete, he blended easily with the “in” crowd, but he kept friendships with disabled students and kids with special needs.

A girl named Cara was one such student and knew John because he always took the time to say hello and ask how she was doing. One day, kids jostling her in the hall gave her a particularly cruel hazing. She escaped around a corner as John was approaching from the other direction. When he saw her, he gave his usual jovial, “Hi!” She was so rattled by the bullying that she lashed out, “F*** you, Johnny Chapman!” and stormed down the corridor. In the hallway, kids laughed or looked away in embarrassment, but John pursued her, matching her quick pace. She tried to make him go away, but he wouldn’t. Instead, he calmed and comforted the distraught girl, sitting with her until after the bell rang and her tormentors had gone.

Later at Windsor Locks High School, a freshman named Kelly sat behind the school on the cold, cement base of a light pole. It was September 1980, several weeks into the new school year and it was Kelly’s first day back after a two-week absence. Her father had died, but she wasn’t ready to be back at school, so she escaped to the solitude of the light pole. She sobbed uncontrollably and didn’t hear someone walk up until he was beside her. She didn’t want to talk to anyone and he just sat next to her, put his hand on her arm, and let her cry. After a bit, he introduced himself, “I’m John, how can I help?” He was a sophomore, a year ahead of Kelly and did not know her, but she knew who he was. Even though he was just in his second year he was already a star athlete on the school’s diving team, competing at the state level. Through halting sobs Kelly told him about her father and said she wanted to go home. She lived across town and it was still school hours, but he told her he would walk her home when she was ready. They talked for a while and instead of going home, he escorted her to the nurses’ office, leaving her with a hug.

Twenty-two years later, at John’s memorial service in Windsor Locks, Kelly needed John’s family to know how much he had impacted her life through that single act of caring. She told his wife, Terry, “I will never forget the kindness shown by this young man, actually still a boy, to a stranger that he saw in pain and couldn’t just walk away from. John was someone who made an impression on me and affected my life in a way I don’t think he ever realized. I will never forget him.”

Tom Allen was the coach of the high school dive team in 1977 and coached John’s older brother, Kevin. But after seeing John dive, he invited John to join the team. In John’s first year, he became fast friends with sophomore teammate Michael Dupont. Over the next two years, they pushed each other to reach for bigger and better dives as they traded placing first and second during their meets. What Michael remembers most about John was, “his competitive drive and the inspiration he gave me while we were diving together. My favorite part about our friendship was during my senior year when we kept trading places on setting new diving records. He broke the record first, then I would beat his record, and back and forth. I believe he still holds the record for high score.” John became the #1 ranked diver in Connecticut, the first in Windsor Locks High School history.

After high school, John enrolled at the University of Connecticut, and studied engineering while on the men’s diving team. He was already ranked #1 in their division for the 1-meter board. He thought he would compete throughout college, complete his degree, find the right woman, followed by the right job, and John Chapman’s life would fall into place.

But as with many young men entering college out of high school, things didn’t turn out that way. By the end of his first semester his grades were so poor he was ineligible to compete. “Studying wasn’t his ‘thing.'” says his sister, Lori. “Doing was his thing.” By August 1985, John made his decision and enlisted in the Air Force promising his mother, that he would try something “safe.” He chose information systems specialist to start his career.

But at basic training at Lackland Air Force Base, he attended a Combat Control Team recruiting briefing. The video showed Combat Controllers jumping from airplanes, riding motorcycles, scuba diving, calling in airstrikes, and directing airplanes to assault zone landings. It struck John at the core with what he desired most, challenge and excitement. Three years later, he returned to Lackland to attend the school informally known as “Indoc,” which at that time was the combined selection course for both Combat Control and Pararescue. The vast majority of volunteers for both jobs inevitably would wash out.

Of the 120 men who arrived at Lackland for Indoc with John, 50 quit or washed out on or before the first day. Graduating with a number of Pararescue candidates, John and his friend Joe Maynor were the only two to graduate in the CCT pipeline. The two graduated the grueling CCT pipeline together in July 1990.

In a single week in 1990, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait and John met Valerie Novak, a young nursing student from Windber, PA. “We went dancing and drinking,” Valerie remember. “We drank lots of tequila.” By week’s end John Chapman, along with the nation of Kuwait, were toast.

Forced to sit out the first Gulf War, John applied to the secretive 24th STS, a national-level special mission unit and the only all-volunteer assignment in the Combat Control community.

He told Val in early 1995, “I want to do this, but if you say ‘No’, I won’t.” Two decades later, Valerie remains convinced that had she said, “No,” the matter would have been dropped without resentment. “But I didn’t want to look back at age 80 and realize I’d kept him from something he wanted so badly.”

By October, they were back in Fayetteville, NC. They bought a house and and in May welcomed a daughter, Madison Elizabeth.

“The first time he held Madison, the spark in his eye was like nothing I’d seen before,” Valerie says. “It was like a kid in a candy store, he was so excited.” They cherished evenings and weekends and found an uneasy rhythm revolving around John’s demanding job and travel schedule. Brianna Lynn was born May 1998.

By the time Brianna turned one, John had turned a corner. The girls had come to be his life and the allure of working with elite Joint Special Operations Command teams waned in the face of his new and true purpose. Val recalls, “When he was home, he was home.” He preferred give the girls their baths and tucking them in to having beers with the boys. “He could have killed 5,000 people at work and, when he walked in the door, you’d never have known,” Valerie said.

He had plans to leave the Air Force when the 9/11 attacks struck. He was no longer even on a tactical team, instead working in the squadron’s survey shop. But war changed everything for the 24th STS. When it emptied out in the first wave, John found himself attached to SEAL Team Six, backfilling other deployed Controllers during the 2001 holiday season. But when his grandmother died, he knew his family needed him more than his nation, so he took emergency leave and returned home to help his folks with the crisis.

Again, it cost him a chance to prove himself in combat.

Fellow Controller and CCT community legend Mike Lamonica recalls retrieving John from Virginia Beach and the long drive they shared back to Ft Bragg. “He had a lot on his mind, and I mostly listened,” as Chappy recalled his time with Val at a prior unit, living on a quiet cul de sac, sitting with other parents, watching their children play. He spoke of how he and Val approached raising the girls as a team. John contrasted his approach with that of many other Combat Controllers, who viewed family as something that came second to missions or career, and how it wasn’t until Madison and Brianna were born that he recognized the error of that approach.

“My job now is to serve my country, but there’s a greater thing than that. When this war is over, I’m going to dedicate myself to my family,” John said.

“You could see the profoundness of the words he was sharing,” Lamonica remembers. “It was intensely personal to him, and it was clear that he and Val loved each other deeply and had discussed those plans as partners.

“He was rebellious against authority, but that doesn’t make him unique in CCT. What really stood out was his humanity and the way he approached family,” Lamonica said.

But first would come a deployment. He famously “stood” on the desk of 24th STS commander, Lt Col Ken Rodriguez, telling him, “with all due respect, I need to get over there now!”

Recalls Rodriguez, “I don’t think we were about to ‘throw down’,” but it was clear the commander needed to send him to war.

On his final morning at home, he kissed Madison and Brianna goodbye and Val drove him to the JSOC compound on Ft Bragg, dropping him at the gate. With a quick kiss and an “I’m out,” John smiled and waved as he walked through the gate. Valerie needed to dash off to work so she turned the car and drove off. They were so used to him coming and going, and the hazards of CCT, “It was just business as usual for us. I didn’t realize it was the last time I was going to see him.”

On 4 March 2002, less than two months later, John died on Roberts Ridge, defending an American helicopter alone, after killing several Taliban fighters. In his wake, he left a legacy of kindness, compassion, devotion to duty, and family. Most importantly to John Chapman would surely have been his two beautiful daughters and wife whom he loved above all else. Rest in peace brother, mission accomplished.

Air Force technical sergeant and Medal of Honor recipient John Chapman was killed on March 4, 2002, fighting alone with his weapons and his hands against Taliban fighters on Roberts Ridge during Operation Anaconda. US forces had evacuated the ridgeline, believing Chapman, a combat controller, was killed in an ambush of the Navy SEAL team with which he was operating. However, later analysis of overhead video, physical evidence, and witness statements showed that Chapman was alive throughout the night after US forces left the site. As a US helicopter approached the ridge, he fired at and killed Taliban fighters targeting the helicopter, drawing their fire, which killed him.

Chapman was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in August 2018, after an extensive review of the Roberts Ridge battle. The medal was accepted by his widow, Valerie Nessel.

The preceding essay on John Chapman’s life prior to the Air Force and his career before Operation Anaconda was written by Dan Schilling, a retired combat controller and author of Alone at Dawn: Medal of Honor Recipient John Chapman and the Untold Story of the World’s Deadliest Special Operations Force with Lori Longfritz.

Read Next: A Ranger Recalls the Actions of Heroes on Roberts Ridge Captured on Video

The Air Commando Journal is written by Air Commandos, for Air Commandos. Our goal is to educate Air Commandos (and all other interested parties) past, present and future on the heritage, history, weapons systems, key units, current operations and overall contributions of Air Commandos towards the preservation of all the values that make this the greatest nation in history.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.