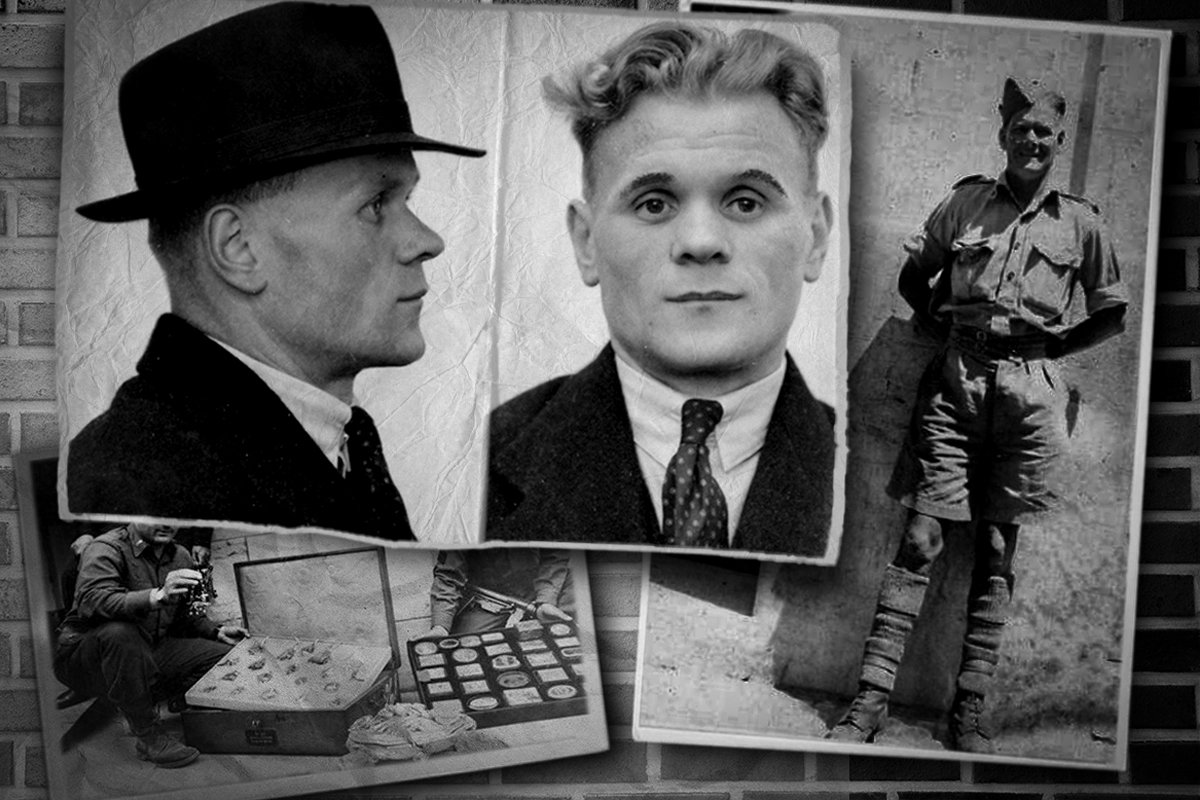

‘Gentle Johnny’ Ramensky: Notorious Safecracker Turned World War II Commando

Composite by Kenna Milaski/Coffee or Die Magazine.

“That’s Johnny’s work,” said a Scotland Yard detective after inspecting an open and empty safe. “Johnny’s back.”

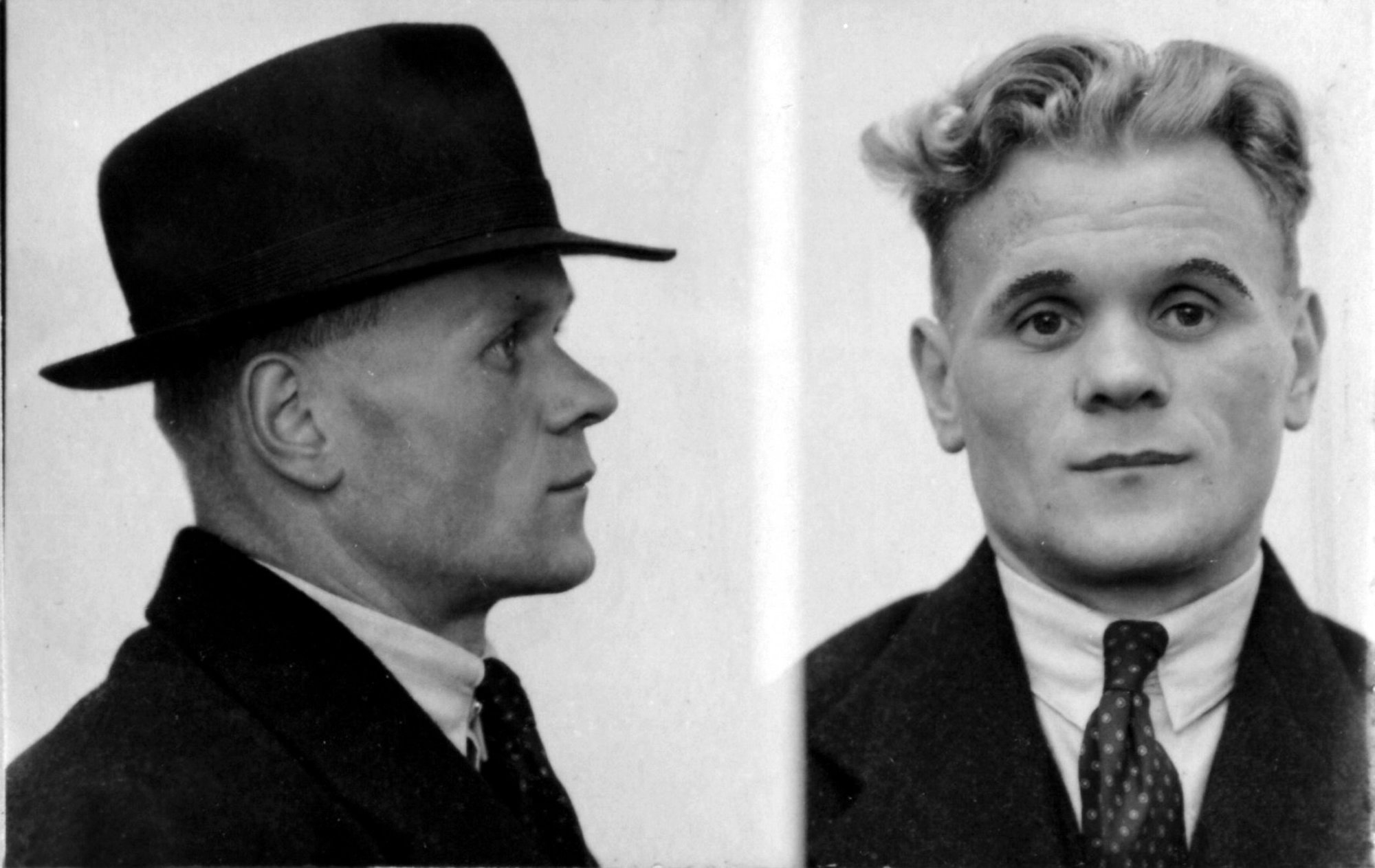

The year was 1951, and their wanted man was among the most well-known safecrackers in the criminal underworld. The meticulous and evasive peterman had earned an envious reputation: No safe was too tough for him to crack. He was a criminal — but he was also a war hero.

“Gentle Johnny” Ramensky avoided confrontation with police, willingly accepting handcuffs around his wrists when he was caught. In a 67-year life span, he spent 40 of them in prison.

His notoriety was extraordinary. Ramensky mixed acrobatic athleticism with his knowledge of dynamite from working in coal mines as a teenager and applied it to his life of crime. He scaled rooftops of businesses and picked locks, but he also had a code. His targets were businesses only and not the homes of ordinary people. Despite being caught and jailed, he had a talent for elaborate prison escapes that were often recalled in sensational headlines in the next day’s paper. The escape artist fled from Peterhead Prison a total of five times.

In 1943, Ramensky’s five-year prison sentence was up. And in the midst of World War II, he was offered a special assignment with 30 Assault Unit. The crackshot commando unit also known as 30AU was commanded by Ian Fleming, a naval intelligence officer and future author who would become famous for creating James Bond. The covert teams arrived in advance of a much larger operation to collect intelligence such as classified documents and codes and to recon enemy troop mobilizations and capabilities.

Ramensky was instructed in hand-to-hand combat, participated in airborne and maritime training, and was consulted for his proficiency in explosives, lock-picking, and safecracking.

The saboteur wreaked havoc on Germany’s railway lines and blasted bridges carrying Nazi supplies. Sometimes his missions were more intimate. He snuck into the North African headquarters of Erwin Rommel and stole the top-secret materials inside. He also targeted Hermann Göring’s luxurious Carinhall estate in the Schorfheide, but his most notorious exploits came when the Allies advanced toward Rome.

Ramensky was dropped by parachute to investigate Germany’s plans in withdrawing from Italy. In one afternoon, he blew open four locked rooms and 10 safes in the German Embassy — some accounts suggest it was as many as 14 safes.

“How did you do it?” his officers would ask, and he’d reply, “That, gentlemen, is my secret.”

While his wartime service was dangerous and threatened more than prison time if he were ever caught, Ramensky was never captured by the enemy. His focus wasn’t entirely on being a commando either — new reports suggest he also acquired stolen Nazi loot and artworks. There were portraits of Adolf Hitler, Eva Braun, Nazi propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels, and the Holocaust architect himself, Heinrich Himmler. The hidden treasure trove was discovered in the Shepton Mallet military prison in Somerset, England, as well as the Royal Navy supply depot in Carfin, Lanarkshire, Scotland.

“Johnny Ramensky was one of our number, a pleasant bloke you never would have guessed was one of the most notorious safebreakers in British history,” said Dennis Whitcombe, another former Scottish commando. “From time to time he would disappear for several days. Even we didn’t know precisely what he had been asked to do although it wasn’t hard to catch the general drift of things.”

Ramensky received the Military Medal for his commando work, and following the war his legend continued to build. “Third Escape This Year — Prison Guards Capture Safecracker-War Hero” was the headline for The Shreveport Journal on Dec. 26, 1958.

When he was free and not behind bars, he chased the next burglary that quelled his need for heightened adrenaline. He once leaped from a moving train after blowing open a safe — not an uncommon occurrence for a man who spent his entire adult life on the run.

“Each man has an ambition and I have fulfilled mine long ago,” wrote Ramensky in one of his diaries. “I cherish my career as a safe blower. In childhood days my feet were planted in the crooked path and took firm root. To each one of us is allotted a niche and I have found mine. Strangely enough, I am happy. For me the die is cast and there is no turning back.”

At age 64, he was caught red-handed on a rooftop in Ayr and thrown in Perth Prison for a year. In 1972, he died in the prison as a result of a massive stroke. Old times die hard.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.