How a Filipino Cook Earned the Medal of Honor and Survived the Bataan Death March

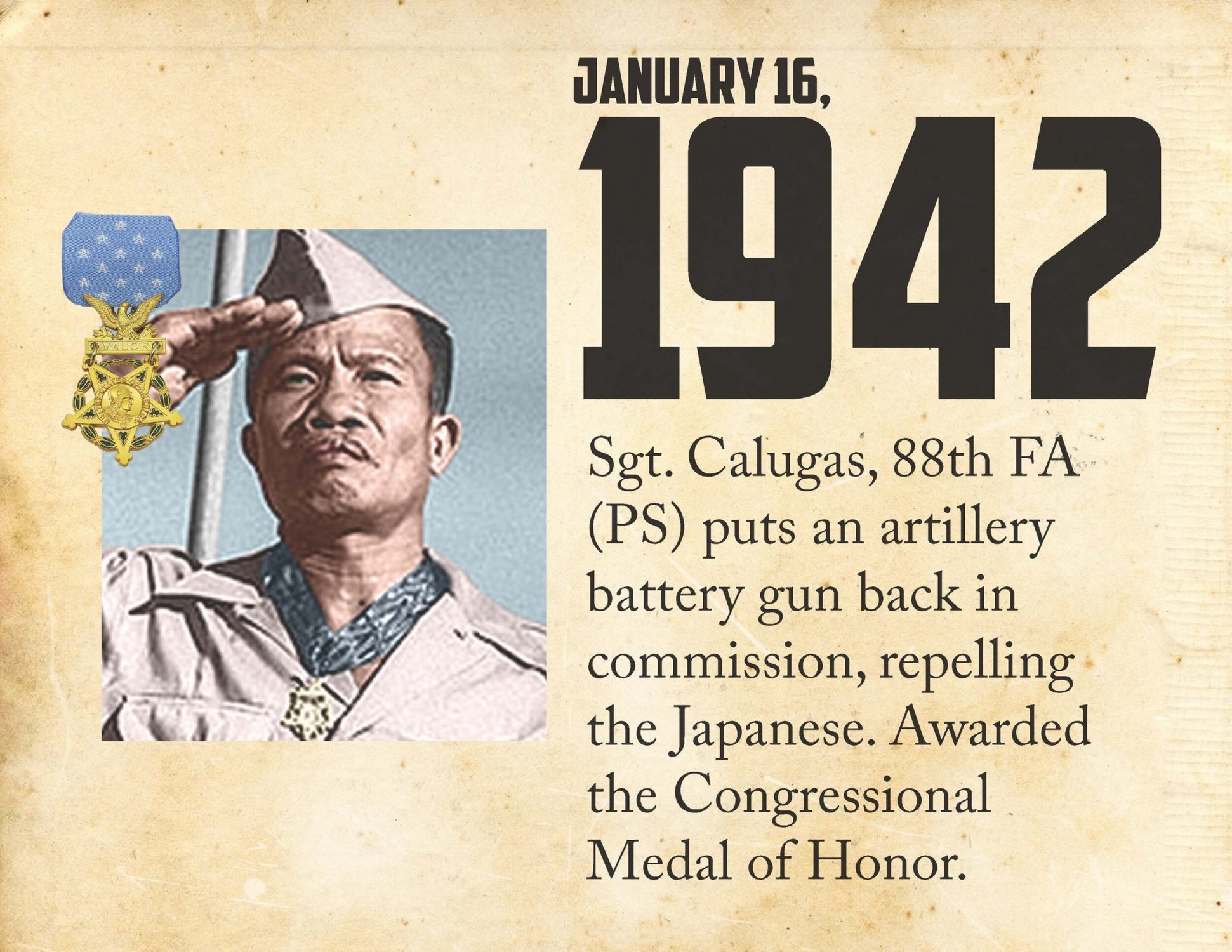

Sgt. Jose Calugas, Philippine Scout, salutes the officer who presented him with the Medal of Honor for gallantry on Bataan. Calugas is the first Filipino to receive this highest award of the United States. Photo courtesy of the National WWII Museum.

Ten hours after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces invaded the Philippines. Gen. Douglas MacArthur ordered US forces from the north and south of the island of Luzon to collapse to the Bataan Peninsula. Among these troops were the Philippine Scouts, native Filipino soldiers who had fought alongside Americans since the unit’s inception in 1901.

The US Army and Philippine Scouts prepared to create pockets of resistance to force the Japanese to fight from line to line. This hastily drawn plan was an attempt to stop the advance in time for emergency resupply and reinforcements. At one of the northernmost pockets of resistance near the village of Culis, the 88th Field Artillery Regiment — the Philippine Scouts — poised for the Japanese assault to commence.

On Jan. 16, 1942, Sgt. Jose Cabalfin Calugas, a 12-year veteran of the Philippine Scouts, was cleaning up after serving lunch in a field kitchen when the first wave of attacking Japanese soldiers arrived. Calugas, who was a cook, scanned across a shell-swept area and locked his eyes onto an American gun position nearly 1,000 yards away. Its silence indicated it was no longer returning fire and the cannoneers inside were either wounded or dead.

Calugas left his own battery and moved across open ground to reach the gun position. He jumped inside, dodging incoming Japanese rifle and artillery fire, and organized a squad to counterattack.

A report detailed how he fired the 75 mm cannon, destroying 60 Japanese vehicles. Although he was recommended for the Medal of Honor on Feb. 24, 1942, his war story wasn’t over.

By April, after seven months of battle exposed to the extreme jungle environment, disease, and without vital supplies, Maj. Gen. Edward “Ned” King Jr. surrendered on Bataan where some 76,000 Americans and Filipinos fell to the 54,000 Japanese serving under the command of Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma. The defeat remains the largest surrender of forces under American command in US history. Calugas was forced into the infamous Bataan Death March, a hellacious 65-mile route to Japanese prisoner-of-war camps.

The Japanese did not offer the POWs basic survival necessities of food, water, and medical treatment, resulting in between 7,000 and 10,000 deaths. During the march, a Japanese soldier smashed Calugas’ head with the butt of his rifle, causing a 3-inch laceration on his scalp. He survived only to endure nearly eight months of captivity inside Camp O’Donnell, where he was subjected to malnourishment and torture. One tactic he used to fool his captors was to exaggerate his symptoms of malaria, shaking uncontrollably each time a Japanese guard came to inspect him.

In January 1943, Calugas was released to work in a Japanese rice mill where he was recruited by resistance fighters to spy against the Japanese. “He escaped and joined squadron #227 Old Bronco unit in October 1943, a guerrilla unit whose headquarter was in Luzon,” his son Jose Calugas Jr. wrote. “The overall command was under Major Robert B. Lapham and executive officer Capt. Harry Mckenzie in Munoz, Nueva Ecija.”

Promoted to second lieutenant in charge of a weapons platoon, he and his unit assaulted a Japanese garrison at Karangalan and later joined the invasion of Munoz, Bongabong, Rizal, and Dingalan Beach. When the Allies liberated the Philippines, he was the first to sign the official registry of the Bataan Death March Survivors and retired as a captain in 1957 after 27 years of military service.

In civilian life he went to college using the GI Bill and graduated with a degree in business administration from the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington, at the ripe age of 55. According to his son, it was his most cherished goal. Calugas organized the Bataan Corregidor Survivors Association in which he worked for 15 years before retiring a second time to a family farm in Washington. Calugas died in 1998.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.