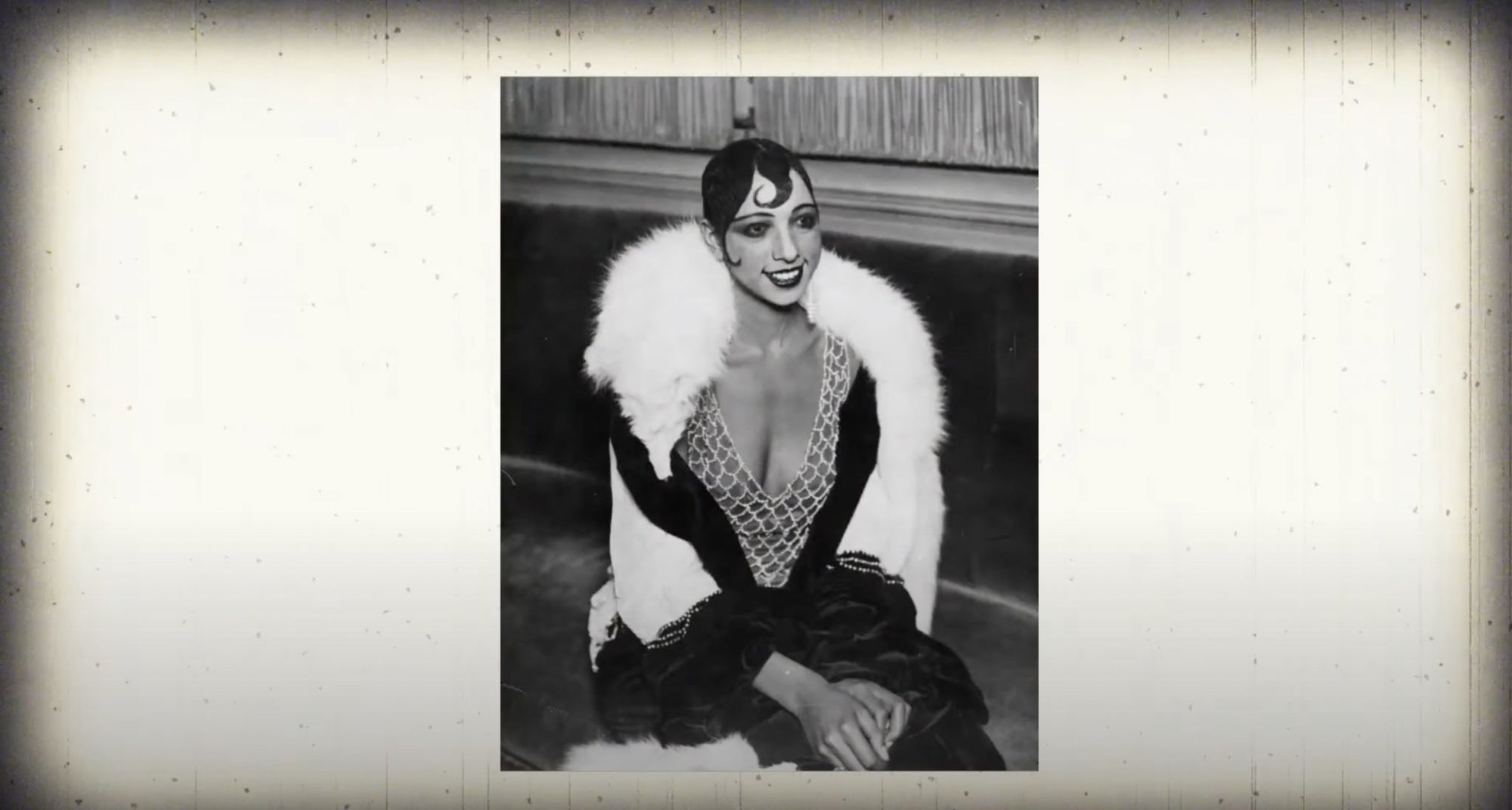

Josephine Baker: Roaring ’20s Symbol of the Jazz Age, World War II Spy, Civil Rights Activist

Composite by Kenna Milaski/Coffee or Die Magazine.

Sitting on a bar stool at the bar of Le Jockey, a classy nightclub in Montparnasse on the Left Bank of Paris, was Ernest Hemingway. African American musicians on stage were playing their saxophones, horns, and drums, while beautiful women danced along.

“One of those nights, I couldn’t take my eyes off a beautiful woman on the dance floor—tall, coffee skin, ebony eyes, long, seductive legs: Very hot night but she was wearing a black fur coat,” Hemingway recounts in A.E. Hotchner’s memoir Hemingway in Love: His Own Story.

“She was dancing with a big British army sergeant, but her eyes were on me as much as my eyes were on her. I got off my bar stool and cut in on the Brit who tried to shoulder me away but the woman left the Brit and slid over to me. The sergeant looked bullets at me. The woman and I introduced ourselves. Her name was Josephine Baker, an American, to my surprise. Said she was about to open at the Folies Bergère, that she’d just come from rehearsal.”

She told him the fur coat was because she had nothing else on underneath. The Brit followed them as they were leaving, exchanging words the entire way, and pulled Hemingway’s sleeve and slammed him against the wall. Hemingway dropped the burly Brit with his fist as the police whistles were sounding. Hemingway spent the night at Baker’s kitchen table, drinking champagne sent from an admirer. They talked all night, “mostly bullshit,” but also about love and their souls.

“Cruel vibes can offend the soul and send it on to a better place,” Baker told Hemingway. “You need some good stuff to happen in your life, Ernie, to rescue you with your soul.”

Baker was as mysterious as she was captivating, and when asked about her flamboyant persona, Hemingway recalled she was “the most sensational woman anyone ever saw … or ever will.”

The American-born performer moved to France from a poverty-stricken home in St. Louis during the Roaring ’20s. Blacks in the United States weren’t welcomed as they were in Europe. The early success of Black entertainers can be credited to Harlem Hellfighter James Reese Europe, who introduced the jazz scene that would rumble across the continent during World War I.

Baker performed in the Harlem music-and-dance ensemble La Revue Nègre. She dressed in provocative outfits, including a skirt strung with bananas (and not much else), while on stage and gained a reputation for her comedic and silly style. Soon she became a star, entertaining open-minded white crowds under the stage name the “Creole Goddess.”

When the Germans invaded Paris in 1940 in the early years of World War II, Baker fled among thousands of others. The 34-year-old was in an interracial marriage with a French-Jewish sugar broker named Jean Lion. She was also openly bisexual and had frequent affairs with women. Had she not fled, she could have been the target of Nazi sympathizers.

She poured out champagne from several bottles and replaced it with gasoline to endure a 300-mile journey to her country estate, Chateau des Milandes. Here she harbored refugees fleeing the Nazis and was later approached by Jacques Abtey, the head of French counterintelligence, to join the French resistance.

“France made me what I am,” she told him. “I will be grateful forever. The people of Paris have given me everything. […] I am ready, captain, to give them my life. You can use me as you wish.”

And he did. She procured visas at her chateau for French resistance fighters and used her celebrity status to attend diplomatic functions held at the Italian embassy. Axis bureaucrats, diplomats, and spies spoke about the war, and she was nearby listening in. She collected intelligence on German troop movements and gathered insight into enemy-controlled harbors and airfields. She’d write notes on her arms and legs with confidence she wouldn’t undergo a strip search.

The Nazis paid her a visit, as they suspected she may have been involved in resistance activities. She charmed her way out of having them search her home, which was filled with hidden resistance fighters, but was spooked enough to contact Abtey to leave France. Gen. Charles de Gaulle instructed the pair to travel through neutral Lisbon, Portugal, to London. Between the two of them, they carried 50 classified documents, including Baker’s notes scribbled in invisible ink on her sheet music.

After the Allies liberated Paris, she returned to her beloved city wearing a French military uniform. De Gaulle awarded her the Croix de Guerre and the Rosette de la Résistance and named her a Chevalier de Légion d’honneur, the highest order of merit for military and civilian actions.

This war hero then became a vocal advocate against segregation and discrimination in the United States in the 1950s and ’60s.

“You know, friends, that I do not lie to you when I tell you I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents,” she said in 1963 at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. “And much more. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad.”

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) named May 20 Josephine Baker Day. She also had a family of adopted children she called her “rainbow tribe” to show that “children of different ethnicities and religions could still be brothers.”

Josephine Baker died on April 12, 1975, at age 68. She preached equality, lived with moxie, and inspired generations of not only Black Americans but all Americans to bring change where it was needed: “Surely the day will come when color means nothing more than the skin tone, when religion is seen uniquely as a way to speak one’s soul; when birth places have the weight of a throw of the dice and all men are born free, when understanding breeds love and brotherhood.”

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.