How the 1st Female Detective Foiled an Assassination Plot Against Abe Lincoln

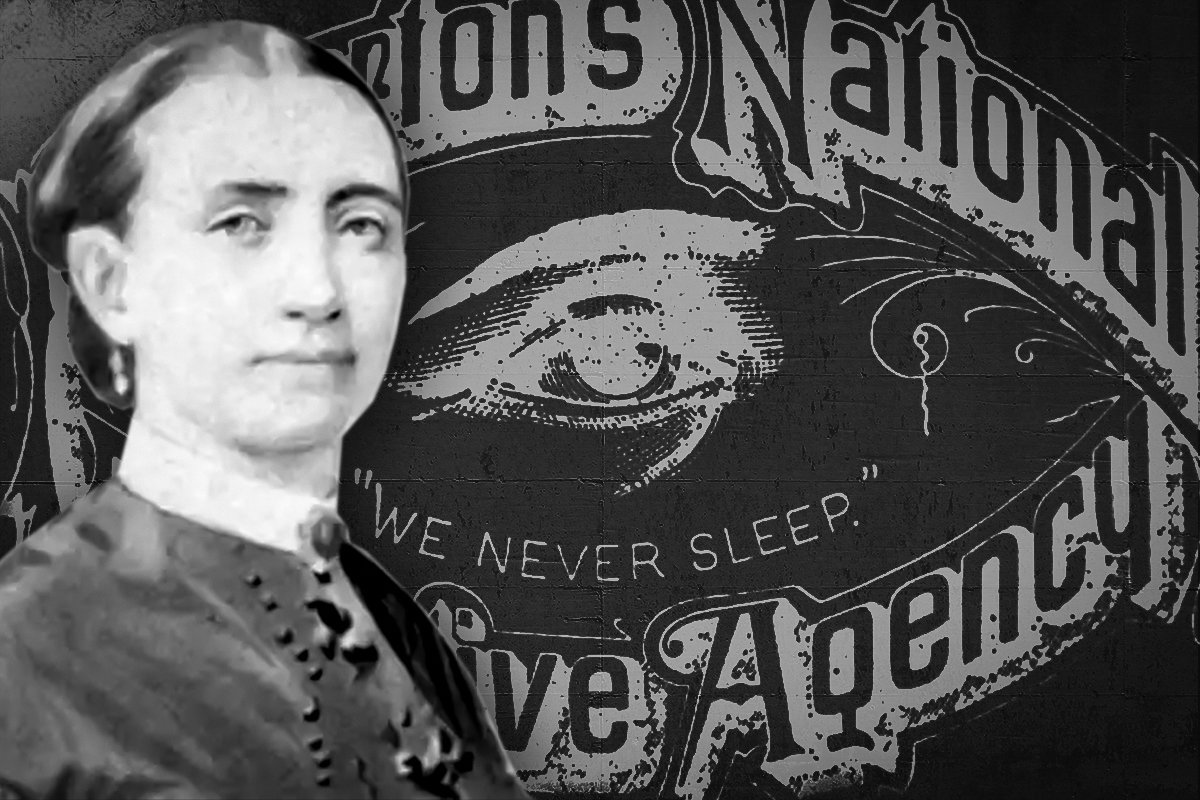

Kate Warne, the country’s first female detective.

“We never sleep,” she thought as she sat beside President-elect Abraham Lincoln. The phrase was the motto of all Pinkerton detectives, but for Kate Warne, the country’s first female detective, it was the mantra to carry her through a historic mission. She and the soon-to-be president posed as siblings, wore disguises, and hid in a sleeping carriage on a night train through Baltimore. Lincoln didn’t have the US Secret Service following his every move, nor did he have the Army providing an escort aboard the train. His whereabouts were a secret, but he was nevertheless in danger, which is how Warne found herself beside him in a train car.

In 1861, Lincoln was set to be inaugurated at the nation’s capital in Washington, DC, and tensions were at a tipping point. It was at the brink of the American Civil War, and those who opposed Lincoln’s position on slavery wanted him dead.

“If any of the Maryland or Virginia gentlemen who have become so threatening and troublesome show their heads or even venture to raise a finger, I shall blow them to hell,” said Gen. Winfield Scott, the Army officer in charge of security in Washington.

But Scott was nowhere to be found on Lincoln’s train ride. Only Warne.

Five years earlier, the 23-year-old widow had approached Allan Pinkerton in Chicago. He had formed Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency around 1850 and specialized in protecting shipments from criminals along the railroad. At the time there were zero female detectives on his force. Pinkerton wrote later that Warne told him she could “go and worm out secrets in many places to which it was impossible for male detectives to gain access.”

She was immediately sent to Montgomery, Alabama, on her first undercover assignment. The Adams Express Co. had been robbed of $50,000 (equivalent to about $1.5 million today), and police had a prime suspect. Warne infiltrated the town, befriended the wife of the suspect, and worked her magic. She got a confession and even the location of the buried money.

“She succeeded far beyond my utmost expectations, and I soon found her an invaluable acquisition to my force,” Pinkerton wrote in his memoir The Expressman and the Detective.

When Pinkerton learned there were rumors about an assassination plot to target Lincoln as he passed through Baltimore during his 11-day whistle-stop tour, he sent his best detective to foil their plans. Warne adopted the disguise of Mrs. Cherry or Mrs. Barley, a socialite and Southern belle from Alabama, and mingled among secessionists at Barnum’s City Hotel in Baltimore’s Monument Square. She used Southern charms learned on her Alabama assignment to meet and mingle with conspirators.

“She was a brilliant conversationalist when so disposed, and could be quite vivacious,” Pinkerton later wrote. “The information she received was invaluable, but as yet the meetings of the chief conspirators had not been entered. Mrs. Warne displayed upon her breast, as did many of the ladies of Baltimore, the black and white cockade, which had been temporarily adopted as the emblem of secession, and many hints were dropped in her presence which found their way to my ears, and were of great benefit to me.”

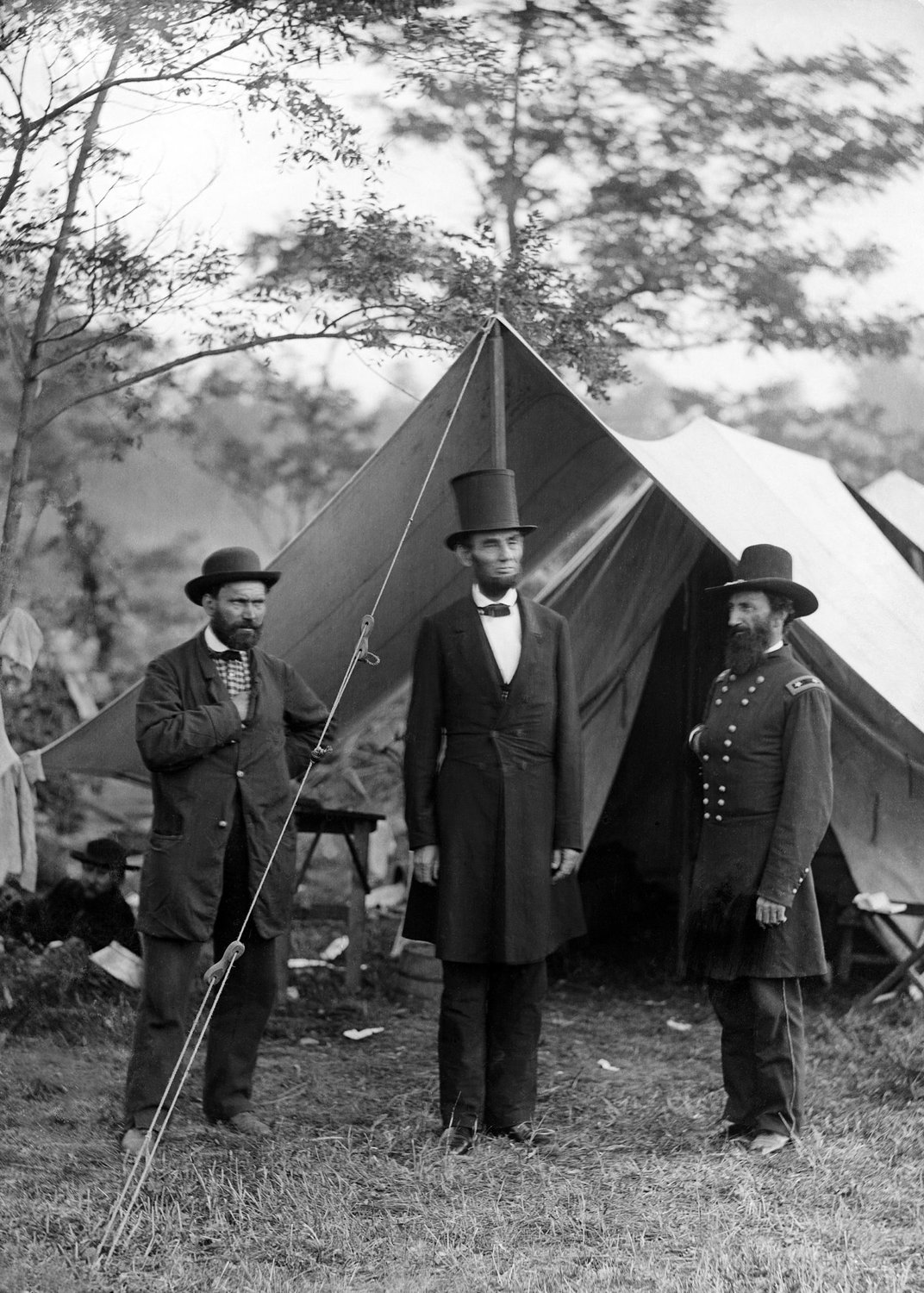

The newspapers printed Lincoln’s schedule for all to see. Pinkerton received intelligence from one of his many undercover detectives in Baltimore that the threat was too serious to ignore. He informed Lincoln a final time that if he were to keep to his normal schedule, “an assault of some kind would be made upon his person with a view to taking his life.”

The only way through the city was in secret, aboard a passenger train with the president-elect code-named “Nuts.” It was part of an elaborate plan Pinkerton and his detectives created to shield Lincoln’s movements as he quietly traveled 200 miles in a single night to reach Washington, DC. The train left Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and arrived at a station in Philadelphia at 10:03 p.m. Waiting for his arrival was Warne, who had flagged down a conductor earlier, bribed him with cash, and informed him she needed a special favor as she would be traveling with her “invalid brother” and they needed their privacy.

They arrived in Baltimore at 3:30 a.m. and the Plums — slang for Pinkerton detectives — telegraphed their success: “Plums has Nuts.” Nine days later, Lincoln was inaugurated as the 16th president of the United States. The assassination attempt was foiled by Pinkerton, Warne, and other detectives who, despite Lincoln’s hesitations, saved him from danger.

Warne and Pinkerton would work together throughout the American Civil War, posing undercover as husband and wife to infiltrate shady circles of the criminal underworld. He appointed her as his superintendent and hired more women to work under her supervision. In 1868, at the age of either 34 or 35, Kate Warne passed away from pneumonia.

Read Next:

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.