Time Magazine reported on the Korean War Armistice agreement in August 1953, a week after its signing on July 27. “A correspondent asked a British officer whether the Commonwealth Division would celebrate with the traditional fireworks,” the author wrote. “‘No’, said the Briton, there is nothing to celebrate. Both sides have lost.”

“The Forgotten War” was three complex years of aerial, maritime, and ground combat. Smashed between World War II and Vietnam, the Korean War saw trailblazers in every way. From ace fighter pilots and medevac helicopter aviators to suicide squads comprised of partisans and U.S. Navy frogmen — the extraordinary perils experienced cannot be understated.

An intelligence blunder from the CIA failed to warn the U.S. government of the invasion over the 38th parallel by describing it in a declassified memo in 1950 as “a defensive measure to offset the growing strength of the offensively minded South Korean Army.” Additionally, 95 percent of the U.S. armed forces were demobilization following the conclusion of WWII, leaving military planners in a bind as strategic special mission units were readily needed and ultimately created on a whim. Sucker-punched into a war they were unprepared for, the detriment was felt and sadly forgotten by many.

Guy “Lucky Pierre” Bordelon: The U.S. Navy’s Lone Ace pilot

The men and women who see adversity early in their careers often prevail, and Lieutenant Guy Bordelon was no exception. With an early interest in flying and a degree from Louisiana State University, “Lucky Pierre” earned his gold wings in May 1943. In the Navy Reserves, flight school proved to be too challenging, which kept him stateside; however, his peers were assigned to the fleet. At the Training Command he served as a “plowback instructor” (first tour instructor), which is what Bordelon credits for his mastery in the art of flight.

It wasn’t until the Korean War that these skills were put to the test. While piloting his piston-engined Vought F4U Corsair alongside his wingman, callsign “team dog,” the pair flew 41 nighttime interdiction missions utilizing their radar to hamper communist transportation systems on the ground.

After “Bed-Check Charlies” — as communist aircraft were called — became such a nuisance in harassment operations against United Nations’ servicemen in the summer of 1953, Bordelon and his squadron were tasked with disrupting them. His team arrived at the U.S. Marine Corps base in Pyeongtaek, Seoul, where he would become the U.S. Navy’s only combat ace. Across two nights spanning June 29 to June 30, 1953, Bordenlon scored four “kills” (two each night) in total darkness just after midnight.

However, his most miraculous feat happened when he intercepted two enemy aircraft on approach for a bombing run targeting the coastal port of Inchon. The circuit connecting his trigger to his weapon systems had fried. Instead of fleeing, he raced ahead of the two enemy aircraft, turned around to face his attackers, put on his blinking landing lights to keep their eyes fixated on him, and lowered his landing gear. Then he zoomed across the sky in an aerial game of chicken; both pilots urgently dove and raised their aircraft in the opposite direction to avoid the collision. Without his fearlessness and ingenuity, both enemy bombers would have released their ordnance on friendly forces.

Wolfpacks, Donkeys, and White Tigers

The partisan forces are often overlooked in wars where large armies and covert operations are intertwined in the same battlespace. Their sacrifice during airborne deep penetration missions was catastrophic. During one mission in January 1953, three U.S. Air Force C-119s and a B-26 Pathfinder were transporting a 97-man “Green Dragon” team to parachute into North Korea. It was the largest operation of its kind during the entire war, and although they received reinforcements and supplies, radio contact decreased and all members vanished without a trace.

This wasn’t a lone occurrence for airborne special operations missions into North Korea. The 8420th Army Unit (it later became Combined Command for Reconnaissance Activities, Korea, or CCRAK) dropped in “Mustang Ranger” teams numbering between five and 20 Koreans in 1952. Their mission was to attack and dismantle frequented railroad lines. None returned.

These partisans were trained at facilities called Wolfpack, Leopard, and Taskforce Kirkland. Their support was veiled as Baker section and assumed the names to describe their units. Some referred to themselves as White Tigers, writes Michael E. Haas in “In The Devil’s Shadow,” because “the title reflected both their high regard for courage as well as the spirituality and immortality symbolized in Korean lore by the tiger.” American advisor First Lieutenant Ben S. Malcolm, a veteran of the OSS and the famed Jedburgh teams, took on the responsibility in training guerilla forces called “Donkeys” on the island of Paengyong-do. This task was even more impressive considering the language barrier.

“The title reflected both their high regard for courage as well as the spirituality and immortality symbolized in Korean lore by the tiger.”

The Donkey teams had a designated “suicide squad,” and Malcolm would witness this firsthand while leading a 120-man Donkey raiding party to assault a machinegun position on July 14, 1952. “The D-4 leader called his [five man] suicide squad to advance upon it…When they reached the wire…four of them opened fire. The fifth man crawled under the wire and moved up to the pillbox[,]…pulled the pins on two grenades and holding one in each hand, the man walked right into the position. This knocked out the position.”

The White Tigers, Donkeys, and Wolfpacks suffered heartbreaking losses. American advisors like Malcolm from the 8420th Army Unit spoke highly of them, whereas Army bureaucracy viewed them as expendable. What happened to the OSS veterans that were still serving after the units disbandment after World War II? Some formed into this temporary unconventional unit that set the foundation for the U.S. Army Special Forces.

Navy Frogmen

The Navy frogmen of the Korean War are often overlooked, though they were part of many historic missions. They belonged to the Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs) and helped evolve the state of Naval Special Warfare for future missions that would aid in the creation of the SEAL teams.

Their ancestors helmed from the OSS Maritime Unit (MU), where nautical sabotage was pioneered, to the Amphibious Scouts & Raiders (S&R), where SWCC capabilities were crafted, to the “Naked Warriors” of the Naval Combat Demolition Units (NCDUs) that assaulted the beaches of Normandy. These units, in combination with the Sino-American Cooperative Organization (SACO) and the U.S. Navy Beach Jumpers, reached such significance that it sealed the UDTs’ reputation as a Swiss Army knife of potential. They led resistance forces, conducted deception and psychological operations, and gathered actionable intelligence.

Though they have secured their legacy, their first mission was a failure. A detachment of frogmen aboard an inflatable boat left the USS Diachenko on a mission to sabotage train tracks and a bridge tunnel near Yeosu on the southern coast of the Korean peninsula. They waited for the signal to infiltrate with two swimmer scouts; Lieutenant (jg) George Atcheson and BM3 Warren “Fins” Foley swam 200 yards to a seawall located below their target. As they conducted a reconnaissance on the beach, they signaled the boat to bring in the explosives. Once they all linked up, a handcar carrying 10 North Korean soldiers appeared from the tunnel and ambushed them. The frogmen scurried back to their boat in a hasty escape while Atcheson covered them with a volley of hand grenades.

In the Wonsan Harbor, William Gianotti conducted the very first combat-diver operation using the aqua-lung to mark the location of a sunken minesweeper.

Despite failing this particular mission, the frogmen carried out several successful operations that proved their worth. During Operation Chromite, they helped search for mines, scouted mud flats, and cleared obstacles to include old boat propellers with explosive devices. In the Wonsan Harbor, William Gianotti conducted the very first combat-diver operation using the aqua-lung to mark the location of a sunken minesweeper. On Christmas Eve 1950, eight frogmen from UDT-3 were responsible for the largest single blast and largest non-nuclear blast since World War II.

The operation destroyed the Hungnam Harbor Facilities with their own plastic explosives and 400 tons of frozen dynamite, 500 1,000-pound aerial bombs, and an estimated 200 drums of gasoline. During this mission, the UDT frogmen endured bitter cold, relentless rain, and precise sniper fire. Their final participation in a major assignment involved destroying the economy by targeting local fishermen. During Operation Fishnet, they worked to reduce the communist forces’ food supplies, which hurt the North Koreans’ ability to sustain their resources and reserves.

The U.S. Air Force Had Boats?

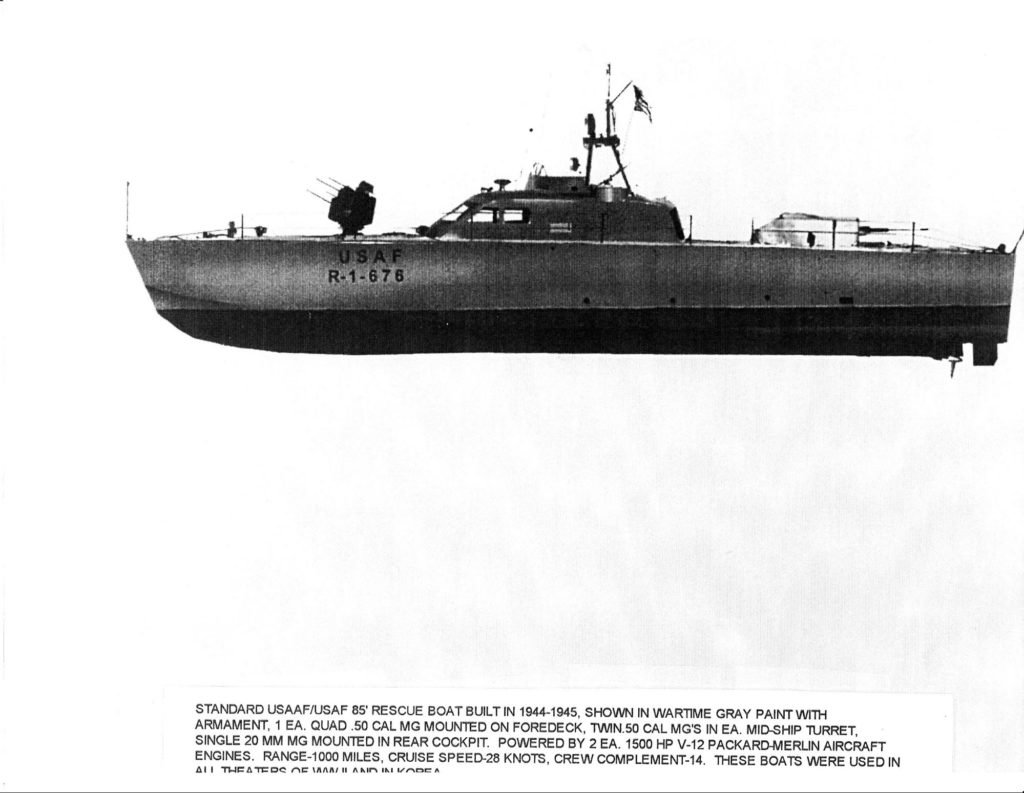

In its infancy, the U.S. Air Force established vessels called “crash boats” (armed rescue boats), which were used to scoop up downed airman who splashed into the drink. Crash Rescue Boat Squadrons (CRBS) sent their 85-foot gray vessels to Guam; Okinawa, Japan; and other ports where they could support this mission.

The boats were equipped with seven .50-caliber Browning heavy machine guns and, according to Haas’ “In The Devil’s Shadow,” four of these guns were on the bow in an arrangement called the “Quad-fifty.” With a range of nearly a mile and the aptitude to fire 2,000 rounds per minute, these agile boats proved useful in supporting covert missions transporting saboteurs and spies to Chinese shores and evacuating UN guerillas. They also had radar, fathometers, and navigational systems that helped them insert into heavily patrolled areas in complete darkness.

These sailor-airmen braved temperatures of 20 degrees below zero, journeyed through thick ice in the Yellow Sea, dodged “Bed-Check Charlies” dropping hand grenades on top of them while orbiting above, and routinely fixed arduous repairs necessary to operating at sea. At times during engagements with coastal batteries or North Korean junk, bullet holes were repaired using tin can lids. The wooden hull was not the best protection, but the crash boats suffered zero losses.

First helicopter pilot to be awarded the MOH

Navy Lieutenant John Kelvin Koelsch had learned a fellow aviator and Marine Captain James Wilkins had been shot down while flying his Corsair during an armed reconnaissance flight over the Kosong mountains in North Korea on July 3, 1951. Piloting his HO3S-1 Sikorski helicopter, he and Petty Officer Third Class George Neal volunteered for the rescue despite the gray clouds and limited visibility. As the sun began to set, the pair understood the risk, flying slow without an escort nor the ability to defend themselves in their unarmed helicopter.

Wilkins had ejected from his plane, landed safely in open terrain, and hid in the treeline to avoid North Korean forces. When he heard the thumping of rotor blades in the distance, he returned to his parachute to make his rescue easier. Koelsch dropped as low as 50 feet to spot Wilkins and, in doing so, flew right into the killzone. Muzzle flashes could be seen in the distance, and bullets ripped through their exterior, causing the helicopter to smoke.

“It was the greatest display of guts I ever saw.”

Neal acted as a spotter and hoisted Wilkins up to them using a custom-made “horse collar” sling on a cable. While they hovered, bullets smashed through the damaged aircraft. “It was the greatest display of guts I ever saw,” Wilkins later recalled of Koelsch completing the mission. The fire grew so intense that Koelsch struggled to keep the aircraft level, eventually crashing into the side of the mountain upside down. Wilkins suffered extreme burns to his legs, but both Koelsch and Neal were unhurt as they scrambled from the wreckage.

They evaded roving patrols for nine days until they were discovered hiding in a hut in a small fishing village along the coast. They were held in isolation and tortured repeatedly, but Koelsch remained an advocate for his fellow prisoners of war (POWs) and refused to cooperate with his captors. He died from dysentery and malnutrition three months later. Koelsch was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 1955, becoming the first helicopter pilot in history to receive the honor.It’s notable that Koelsch had a degree from Princeton University and eschewed a promising law career to participate in the war that cost him his life. The Navy did not forget his sacrifice and immortalized his memory with the Garcia-classed destroyer escort USS Koelsch (later christened frigate FF-1049 in 1975) and named a flight simulator in Hawaii after him.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.