PFC Charley Havlat: The Last American Combat Death of World War II in Europe

A crowd gathers in Times Square celebrating with a newspaper the surrender of Germany.

Adolf Hitler killed himself on April 30, 1945, but his death didn’t bring an end to the fighting of World War II or the work that had to be done. While many German units were standing down, Allied troops fought German holdouts right up until Germany’s unconditional surrender on Victory in Europe Day — better known as VE Day — on May 8.

The last American soldier killed in combat in Europe died just minutes after German and Allied officers had negotiated a ceasefire and a few hours before the German army’s surrender. The son of Czech immigrants, Private First Class Charles “Charley” Havlat died liberating his parents’ homeland from the Nazis.

Havlat was born on Nov. 10, 1910, in Dorchester, Nebraska. He was the eldest of six children born to Anton Havlat and Antonia Nemec, who immigrated to America in the early 1900s. The Havlat children grew up steeped in the cultural traditions of their parents’ motherland — they spoke Czech at home and bragged to their friends about the kolaches their mother cooked.

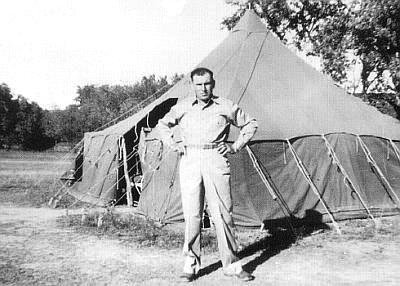

Havlat worked as a farmhand for $1 a day before eventually starting a trucking company with his cousin. The U.S. Army drafted him in 1942, and he and his brother Rudy both joined the 803rd Tank Destroyer Battalion. Havlat was assigned to the battalion’s recon company.

The 803rd landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day and fought its way inland to Saint-Lô. The battalion continued across northern France and saw combat in some of the war’s fiercest battles. The Havlats fought at Aachen and the Hürtgen Forest, and they were in the Ardennes Forest when the Battle of the Bulge began on Dec. 16, 1944.

After the Allies broke German lines in the Ardennes, the 803rd helped capture Trier, Germany, and crossed the Rhine. Eventually, Charley and Rudy found themselves in their parents’ homeland, helping liberate the Czech town of Volary from the Germans. During these operations, troops of the 803rd also rescued a group of starving young Jewish women who’d somehow managed to survive the Nazi’s horrific extermination operations.

On May 7, 1945, Charley’s platoon was conducting a recon mission on a dirt road in the woods when they took heavy fire from troops of the 11th Panzer Division. The Germans attacked with machine gun and small arms fire from concealed positions in the trees. They fired four panzerfausts at the Americans’ lead vehicle — an M8 armored car. They exploded around it, bringing the Americans to a stop.

Charley was in the second vehicle, an unarmored open-top jeep. He ducked down behind the hood, but when he peeked his head up to see what was happening, a German bullet struck him directly in the forehead, killing him instantly. The Americans returned fire until their radio operator received word that a ceasefire order had gone into effect and they had orders to withdraw back to Volary immediately. Charley was the only fatality.

It turned out the ceasefire went into effect just nine minutes before Charley died. Just a few hours after the attack, the German military surrendered. The German officer who led the ambush was captured not long after. He told the Americans he knew nothing of the ceasefire until 30 minutes after and apologized for Charley’s death. The next day, Nazi Germany unconditionally surrendered.

As a fellow member of the 803rd, Rudy learned of Charley’s death when his comrades returned to Volary. But their brother Adolph — the youngest of the Havlat children and another GI serving in Europe — didn’t get the word for weeks. In fact, on VE Day, he wrote home to his mother telling her that they’d all be home soon.

Adolph was serving with Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), assigned to the prisoner-of-war and displaced persons division assisting POWs, refugees, and Holocaust survivors. He was in Frankfurt, Germany, when he finally learned of his brother’s death.

Adolph’s commander granted him leave, and he hitchhiked his way to meet Rudy so they could pay respect to their brother. Afterward, Adolph returned to SHAEF — there was still a lot of work to do. Though the war was over, the resettlement of refugees and repatriation of POWs would prove to be a long and difficult process that would ultimately go on for decades.

American troops left Volary as the Red Army took over occupation duties in Czechoslovakia and propped up a pro-Soviet government. It quickly became apparent that repressive Nazi rule had merely been replaced by repressive Communist rule. As the Soviet Union tightened its grip on Czechoslovakia and the Iron Curtain fell across Eastern Europe, thousands more Czechs, Slovakians, and other Eastern Europeans became refugees as they fled to the west. Many of these refugees, like the Havlats, made their way to America to start new lives.

Today, Charley Havlat has a permanent grave at the Saint Avold World War II veterans cemetery near Metz, France. In the modern-day Czech Republic, a Czech military club paid for a memorial plaque placed at the spot where he died.

Kevin Knodell is a freelance journalist and author. His work has appeared at Foreign Policy, Playboy, Soldier of Fortune, and others. He’s the associate producer of the War College Podcast and a former contributing editor at Warisboring. He’s the co-author of the graphic novels The ‘Stan and Machete Squad, and he currently writes the Acts of Valor comic series for Naval History magazine.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.