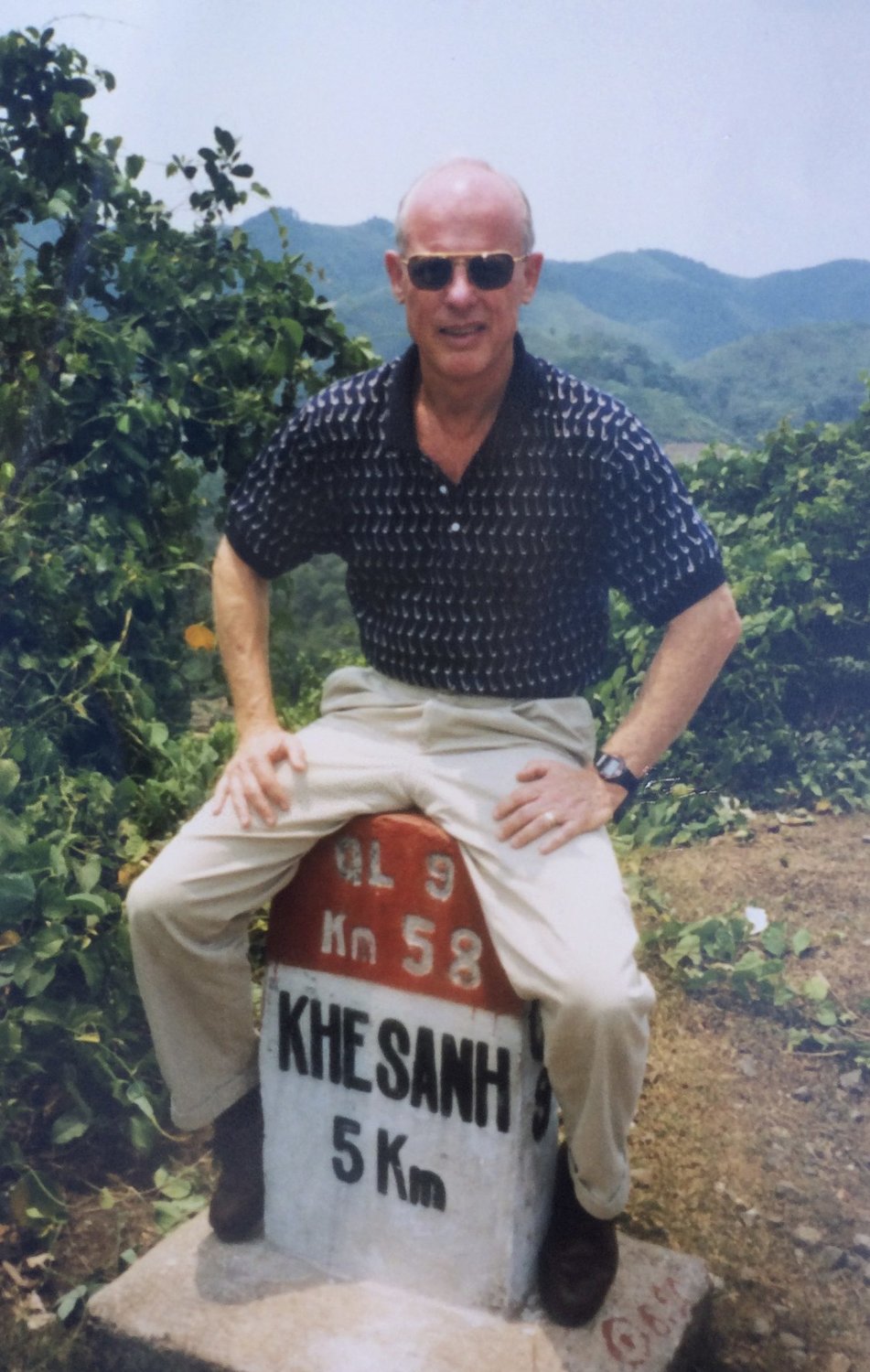

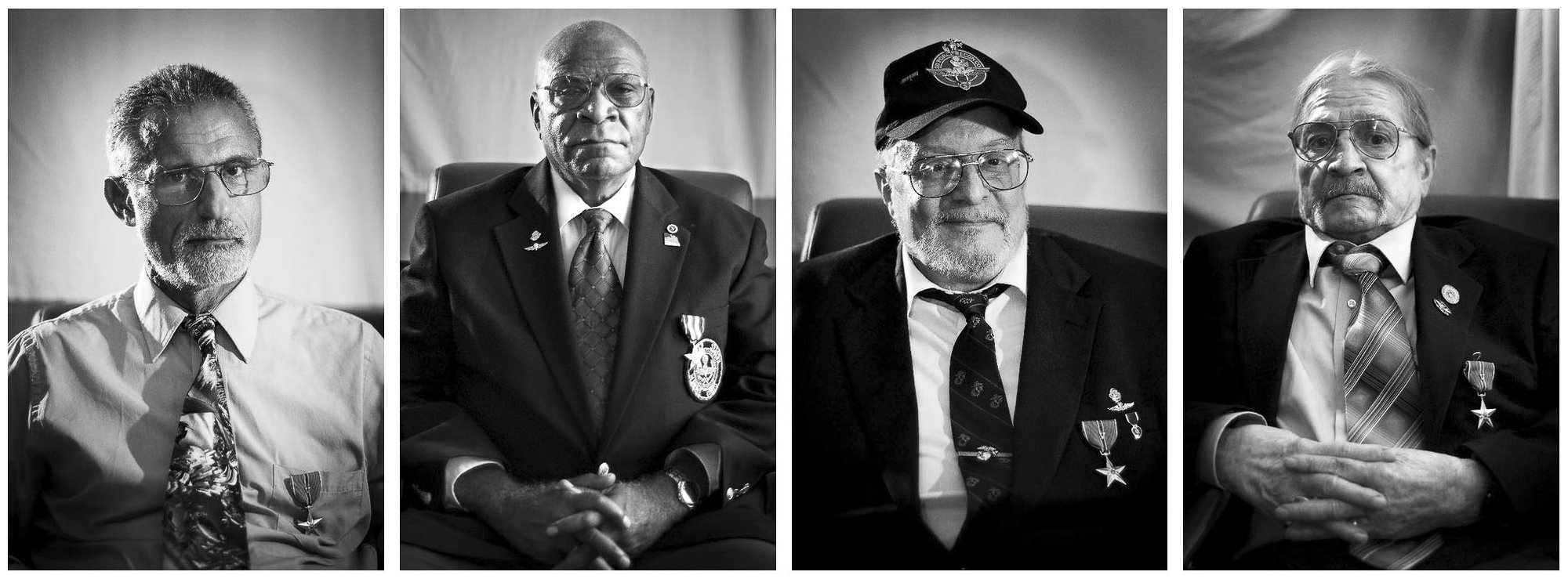

James Capers Jr. in 2013. Photo by Ethan E. Rocke.

It was around dawn on Feb. 19, 2012, when the phone rang in an apartment in Oceanside, California, rousting retired Marine Maj. James Capers Jr. from a deep sleep. Capers looked for the sound, his 73-year-old brain still soaked with the residue of his nightly Ambien. He found the phone and picked up. The voice on the other end was frenzied: “They have me surrounded, sir! They’re coming to get me! I didn’t do anything wrong!”

Capers thought it must be a dream. The voice belonged to James Dixon III, the young Iraq war veteran who, just weeks earlier, had been living with Capers, helping him with his memoir. The ramblings continued: “You’re going to get the Medal of Honor, sir. You’re going to get it … I love you. I miss you.” Who has him surrounded? Capers thought. He tried to calm Dixon. He figured the young man must have had too much to drink. Alcohol never mixed well with Dixon’s post-traumatic stress.

Capers had come to regard Dixon like a son. He had been a key member of the administrative team that put together Capers’ Medal of Honor nomination in 2008, 41 years after Capers’ combat tour in Vietnam. Capers is a legend of the Marine Corps’ elite Force Reconnaissance community, and Dixon wanted to see him become the first Black Marine officer ever to receive America’s highest military honor.

“Take it easy,” Capers pleaded. “I’ll come to Georgia and we’ll sort this out together, son. I’m going to take care of you. Just calm down.” The line went dead.

Capers tried calling back. No answer.

Minutes later, he got a call from Dixon’s father.

James Dixon III was dead.

Death is a common refrain in Jim Capers’ life. In Vietnam, death was Capers’ business — inflicting and avoiding it, and generally coping with its inescapable centrality. When death failed to take Capers during a bloody ambush in Vietnam, it followed him home. There were no parades or homecomings for Capers’ generation of veterans. Suicide, drugs, alcohol, violence — death continued to call, and Capers became all too familiar with the destructive patterns into which so many veterans fall.

Cpl. James Monroe “Rooster” Dixon III was assigned to the 2nd Marine Division’s personnel and administration section in 2007. The assignment was meant to be a change of speed for Dixon, who had severe PTS from three tours as an infantryman in Iraq and was waiting to hear if he would be approved for medical retirement for his psychological trauma. A Georgian from the tiny town of Baxley, Dixon had a thick drawl, an endearing laugh, and unruly hair that earned him the nickname Rooster. He earned an MBA from Georgia Southern University and was highly intelligent, fiercely loyal, and deeply passionate about taking care of Marines.

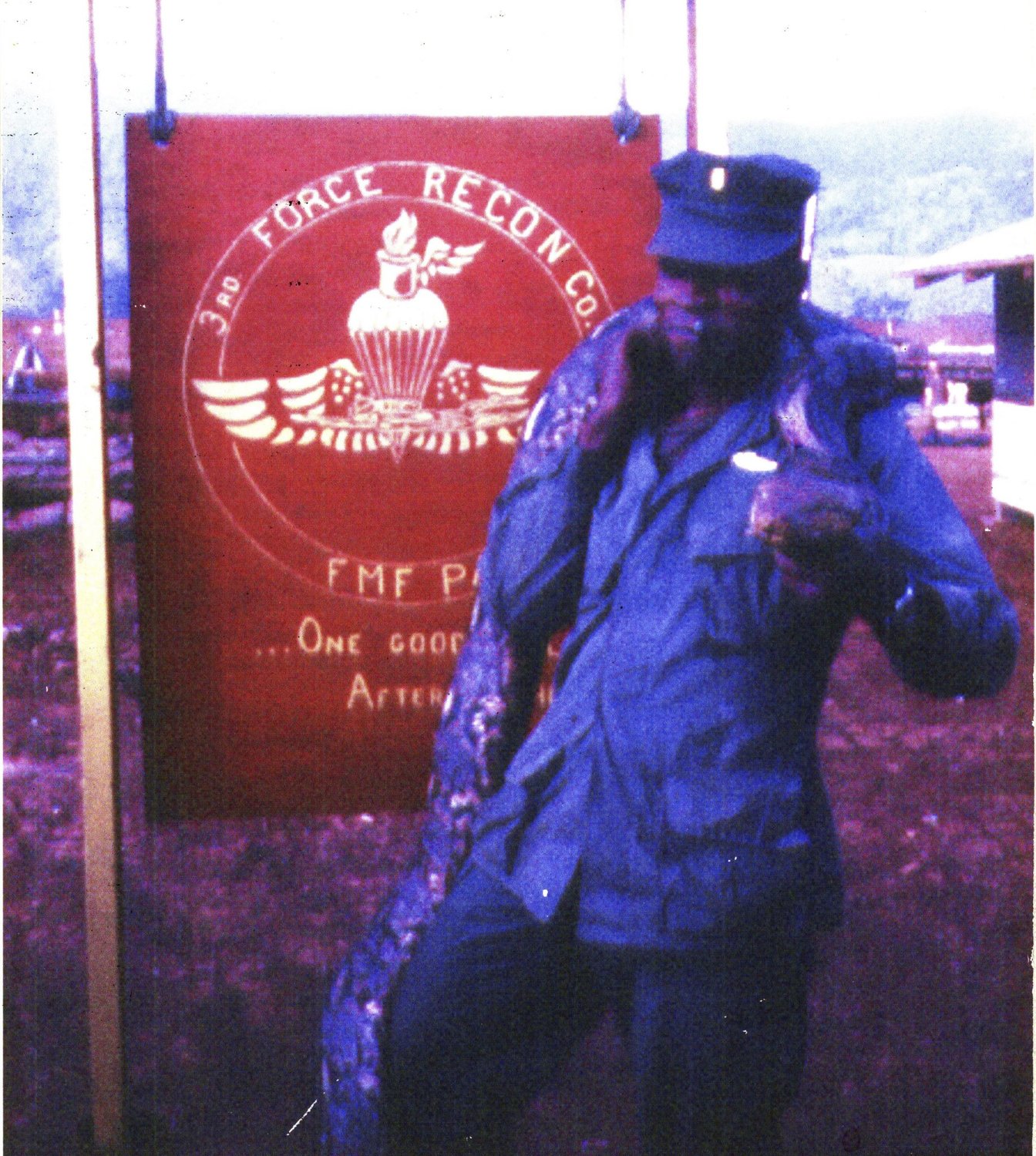

For several months in 2007, Capers joined Dixon at the 2nd Marine Division Headquarters building, helping to put together dozens of recommendations for medals and medal upgrades for Capers and the Marines of 3rd Force Reconnaissance Company. The detachment of 3rd Force Marines who served in Vietnam in 1966 and ’67 had come to be known as “the lost detachment” because administrative records of their exploits were lost for years.

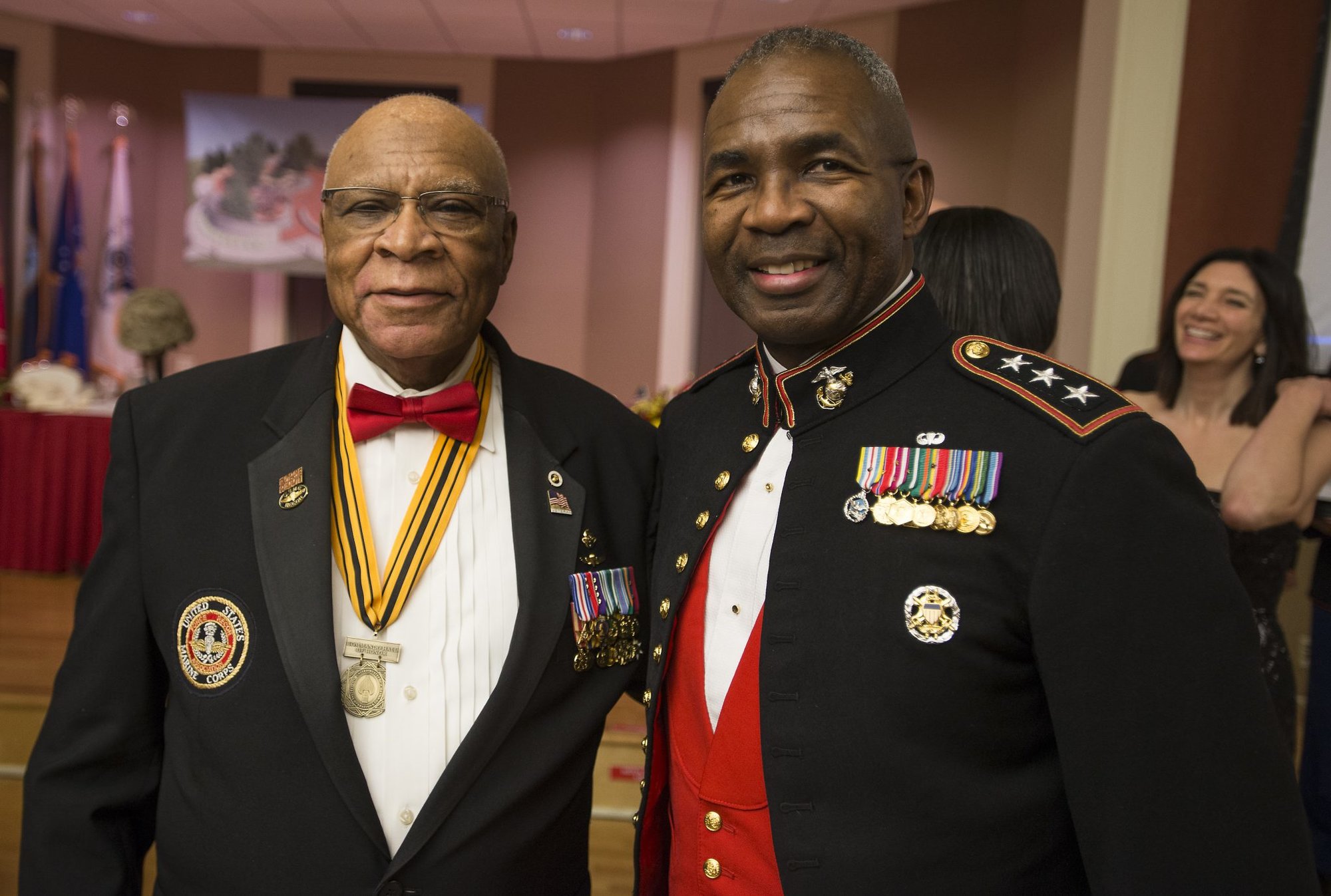

As assistant division commander for 2nd Marine Division in 2007, then Brig Gen. James L. Williams believed Capers’ actions in Vietnam were worthy of the Medal of Honor. His boss, 2nd Marine Division Commander Maj. Gen. Walter Gaskin, agreed, and with Gaskin’s support, Williams led the effort to have the Marines recognized 40 years after their combat tour.

Dixon became the backbone of the project. He had been wounded in Anbar province, and when it became his duty to investigate and prepare the dozens of award nominations, he felt a kinship to the 3rd Force Marines. He was amazed by the accounts he heard from Capers’ men and by Capers’ humble and fatherly nature, and he spent more than a year making hundreds of phone calls, mailing letters, and conducting countless interviews to prepare dozens of award recommendations and upgrades, including Capers’ Medal of Honor package.

Of the more than 3,500 Medals of Honor awarded since the medal was established early in the Civil War, most have been in recognition of exceptional performance over a period of short duration — days, minutes, or even seconds. In Capers’ case, however, Williams and his staff believed Capers’ numerous acts of heroism and the lethality he brought to bear against the enemy during his eight-month tour in Vietnam demanded no less than the nation’s highest award for valor.

[vimeo id=”91033295″ /]

In late January 1967, Capt. Ken Jordan, a rangy Texan with sandy blond hair, selected Capers as his assistant patrol leader for a risky mission handed down from the CIA. A Viet Cong defector had claimed that four American prisoners of war were being held in a Viet Cong camp, and the Marines of 3rd Force were charged with getting them out. Eight other Marines, an interpreter, and the defector rounded out the team led by Jordan and Capers. The top-secret operation was code-named “Doubletalk.”

They dropped one by one from a CH-46 helicopter into the cold and rain-soaked jungle near the border of Laos in central Vietnam. They were some 20 miles behind enemy lines.

As the noise of the chopper grew faint, the commandos silently proceeded through the jungle. After three days, they found the camp abandoned. Some of the team quickly formed a security perimeter, while others began documenting what they found. Jordan stood with his back to a tree, surveying the eerie scene. Suddenly, a noise from the woods, followed by a blast from one of the Marines’ M16s, ruptured three days of perfect tactical silence, and a Viet Cong soldier collapsed into the bush.

Spotting another VC soldier aiming a gun directly at him from 15 meters away, Jordan swung his M16 up and squeezed the trigger, dropping his would-be killer. Within seconds, the team was racing through the jungle, a Viet Cong response force amassing in its wake.

As the commandos moved swiftly through the bush, Capers dropped back to booby-trap the path behind them with grenades. The enemy was everywhere, but for hours, the team evaded them. Sgt. Ron Yerman, the radio operator, called for extraction, and they made their way up a steep, rutted slope to higher ground. The topography was less than ideal, forcing the CH-46 to hover above the thick jungle canopy while it lowered a harness to hoist the men one by one. Bullets began whipping in from all directions. Above, the helicopter’s .50-caliber machine guns roared to life, hammering the wilderness around them.

As the commandos were hoisted into the chopper, Capers darted from tree to rock to tree again, squeezing off a few rounds at each point to give the illusion that there were multiple soldiers still on the ground.

The harness finally descended once more. After struggling to secure himself, Capers was lifted into the air. As he dangled, a single round slashed his face.

“It was a grazing wound, but it burned like hell,” Capers said.

Years later, in his statement supporting Capers’ Medal of Honor recommendation, Yerman credited Capers for getting the team out alive: “Chaos ensued, and Lt. Capers took charge and organized a rapid egress toward a landing zone. He was the most professional Marine I ever knew.”

Lowell Burwell was the Navy corpsman on the patrol, and in his witness statement, Burwell described Capers’ performance: “2dLt Capers was the cement that held the group together … Lt. Capers’ combat experience and professional expertise … lifted the spirits of the troops.”

Jordan received the Silver Star for his actions as patrol leader on the mission, and Capers received a Bronze Star for his role as assistant patrol leader.

The Silver Star is awarded for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action,” and Jordan said the philosophy in the Marine Corps when he received the medal was that the senior officer in charge of a high-profile mission like the POW raid was typically seen as deserving the highest award because he bore the greatest responsibility for the mission’s success or failure.

“Jordan was one of the first Marines up into the bird, which was strange to me because when Capers led patrols, he always insisted on being the last man on the ground,” Yerman said. “He would never get in the bird before every other Marine was accounted for and safely on board.”

Rank is not supposed to be a factor when considering valor awards, but the Marines’ official guidance on determining appropriate awards tasks commanders to consider all the specific aspects of a Marine’s actions “in comparison to the actions of others in that command or theater of operations,” meaning officers must judge the merits of an award relative to the actions of others. Often, those others include themselves.

Jordan, who served as the lost detachment’s commander throughout most of its tour in Vietnam, was the only Marine in Capers’ chain of command who opposed his Medal of Honor nomination in 2007. In a letter to a Pentagon official James Dixon drafted three weeks before his death, Dixon described how Jordan, a retired colonel, had been adamant in his opposition.

“His exact words were, ‘Not only no, but hell no!’” Dixon wrote.

Born to a South Carolina sharecropper in 1937, Capers is a child of the Jim Crow South. Four of his seven brothers and sisters died before the age of 10. In 1943, after a local sheriff issued a warrant for his arrest, Capers’ father fled to Baltimore, and the family soon followed.

“My father was a violent man,” Capers recalled. “He got into an altercation. I’m not sure if the crime was serious enough for a lynching, but he felt that to survive, we had to leave South Carolina.”

In Baltimore, the Caperses were poor, but his mom ran a tight household, and they got by. Capers was a smart, restless 18-year-old kid when he enlisted in the Marines with a high school pal in 1956.

“A lot of people had helped me and my family get by,” he said, “and the Marine Corps seemed like a good way to give something back.”

On the hot September day he left for boot camp, his father drove him to the train station. The elder Capers had served time on a chain gang, and he understood the struggle of being a Black American in the 1950s.

“You’re a man now,” his father told him. “You know what you’ve gotten into. You’ve chosen it.”

From day one, Capers was determined to distinguish himself among his white peers.

“The Marine Corps did not welcome individuals like me,” he said. “But the hierarchy thought, ‘If he’s got the skills, at least give him the chance to try.’ That’s all I wanted.”

[vimeo id=”91028301″ /]

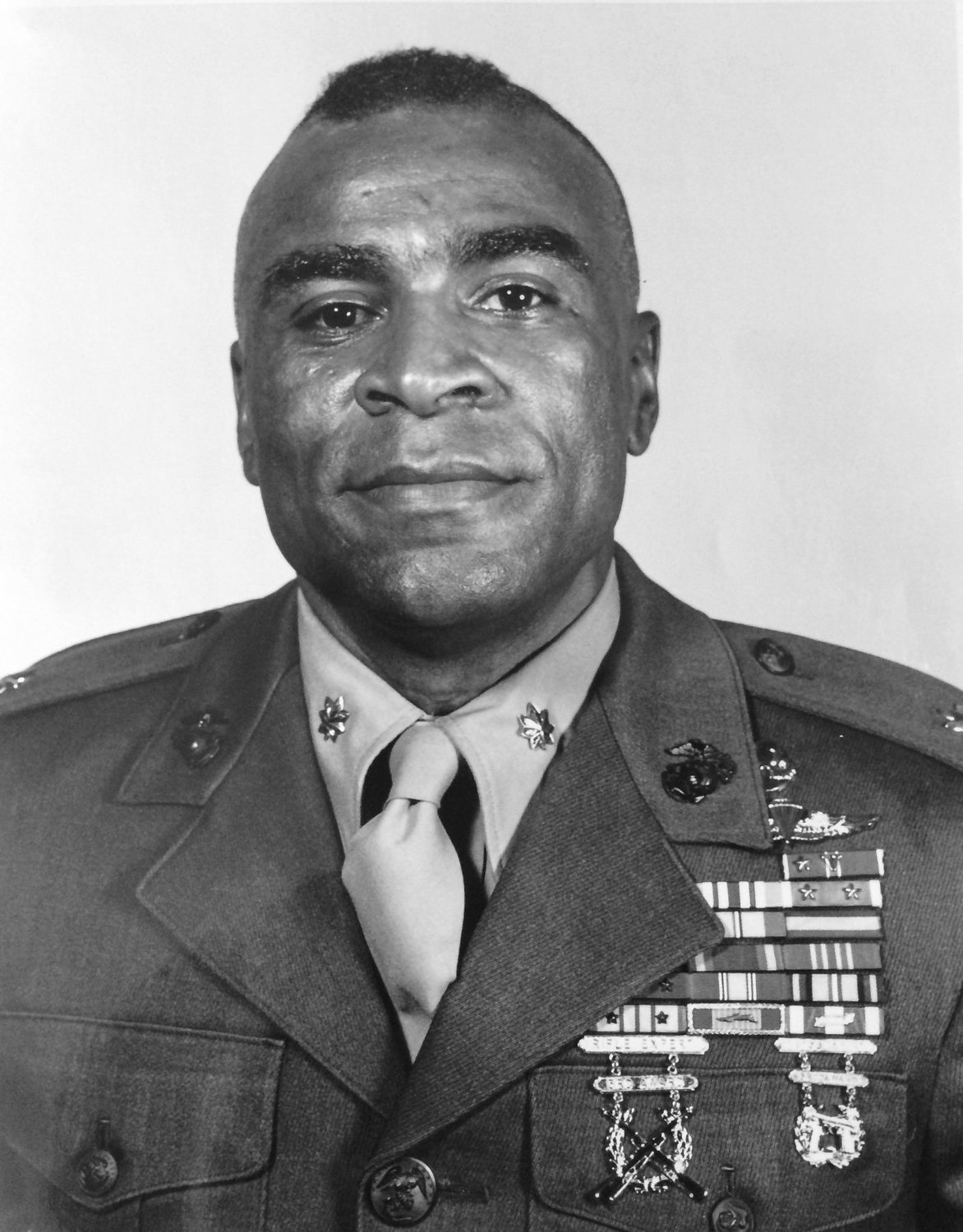

Capers was, by all accounts, an extraordinary Marine and combat leader. His exemplary record of dangerous missions and tactical innovations earned him a place in the US Special Operations Command’s Commando Hall of Honor. The day he was inducted into the hall in October 2010, Maj. Gen. Paul E. Lefebvre, then commander of Marine Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC), called Capers “the spiritual founder of Marine Corps special operations.” There is a conference room named for Capers at MARSOC’s headquarters.

Early in his career, Capers volunteered for duty with the 1st Force Reconnaissance Company. Until MARSOC was established in 2006, Force Reconnaissance companies were the Corps’ only special operations units, specializing in unconventional warfare tactics similar to the Navy SEALs and Army Special Forces. Force Recon requires extraordinary swimming ability, and Capers was one of the first to earn his place in special operations and defeat the stereotype that Black Marines can’t swim.

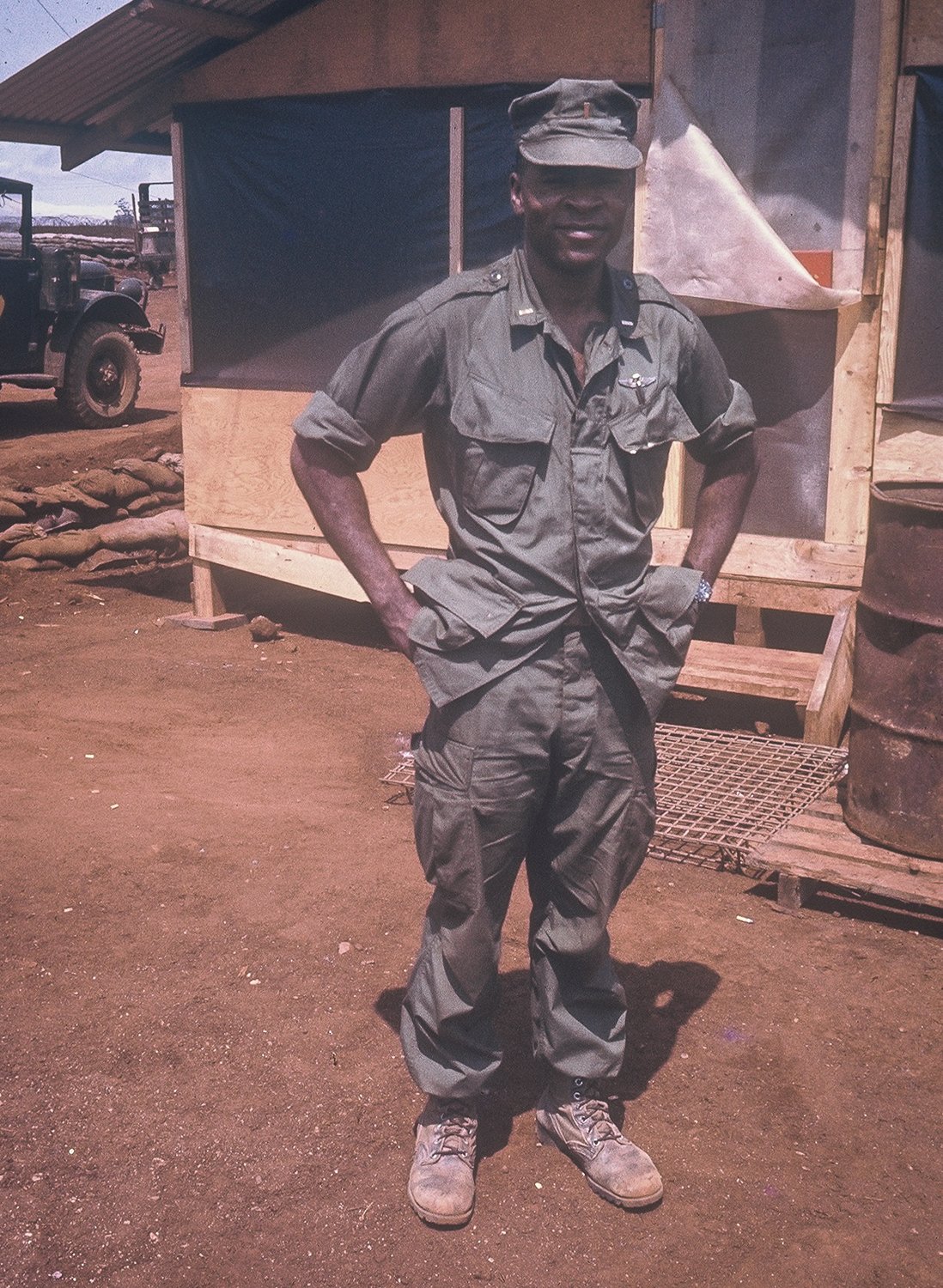

In 1965, he volunteered for duty in Vietnam with the newly formed 3rd Force Recon Company. With a reputation as a noncommissioned officer entirely devoted to the Corps and its values, Capers was placed in charge of an all-white 20-man platoon. With his hard stare and formidable build, his authority was never in question.

[vimeo id=”91031534″ /]

“[He] was standing in front of the formation with confidence and charisma,” one of his men wrote in a statement. “I am Sergeant Capers,” he told them, “and we will be the best platoon of Marines in the world.”

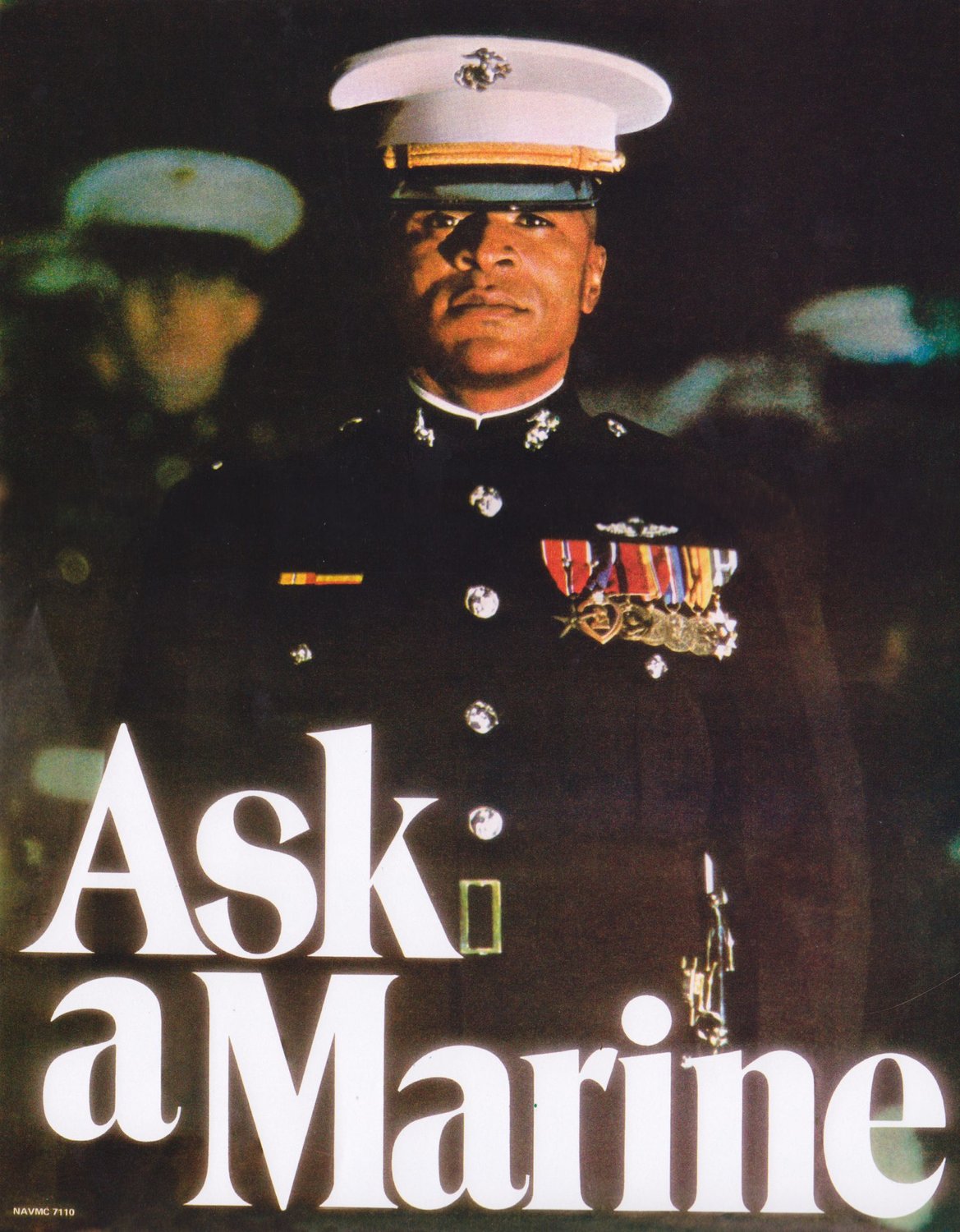

So thoroughly did he represent the ideals and mythology of the Corps that his picture graced a near-ubiquitous and highly successful recruiting poster focused on attracting minority officers in the early ’70s. In the ASK A MARINE campaign, Capers reflects an ideal of Marine Corps grandeur.

In April 1966, 3rd Force Reconnaissance Company’s 1st and 5th Platoons, each composed of 20 men, deployed as Forward Detachment, 3rd Force Reconnaissance Company. They arrived in-country just as the most brutal and crucial phase of the war was getting underway. Their primary mission was to gather critical intelligence, usually with little support and few resources.

“I wasn’t afraid because I had a job to do, and my job was to lead and to look out for my guys,” Capers recalled.

By November, the detachment had taken many casualties, including two officers killed in action. Capers — then a staff sergeant with 10 years of service — had proven himself an exceptional combat leader. He’d led underwater dive missions off the coast of Vietnam in May, fought in several amphibious landing operations in August and September, rescued a Marine unit that had been cut off from friendly lines, led his team out of a hellish five-day patrol to locate the wreckage of an American aircraft deep behind enemy lines. He was a graduate of nearly every special tactics school or qualification course the military could offer, and he had also earned a black belt in karate on his own time and was a qualified sensei.

On Nov. 30, 1966, Capers reported to his battalion commander’s tent at the combat base in Phu Bai, where Lt. Col. Gary Wilder told him to raise his right hand to take the oath to become a commissioned officer. The detachment commander, Capt. Ken Jordan — the same man who would later oppose Capers’ Medal of Honor nomination — was there to pin on the old set of second lieutenant rank insignia he scrounged up for the ceremony. Afterward, Wilder and Jordan congratulated Capers on his achievement. During the entire Vietnam War, only 62 enlisted men were battlefield commissioned. It was a surreal but proud moment for Capers. He had applied for the commissioning program twice before deploying to Vietnam, and his application had been “considered but not selected.”

“A lot of the Negro Marines came over and saluted me and shook my hand,” Capers recalled. “And these were guys who I felt had paved the way for me, guys who had been through the segregation years and World War II and Korea. Suddenly I was a lieutenant, and they were saying ‘sir’ to me. It felt odd because these were men who I looked up to.”

Capers knew it was standard procedure to transfer newly commissioned officers to another unit. For him, that would have meant assuming a more comfortable, less dangerous role in the war. Not willing to abandon his men, he requested to stay with his team, which had adopted the nickname Broadminded — a nod to its reputation for cold-eyed efficiency. Jordan and Wilder granted Capers’ request, and he returned to the fight, leading patrols as if nothing had changed.

[vimeo id=”91032879″ /]

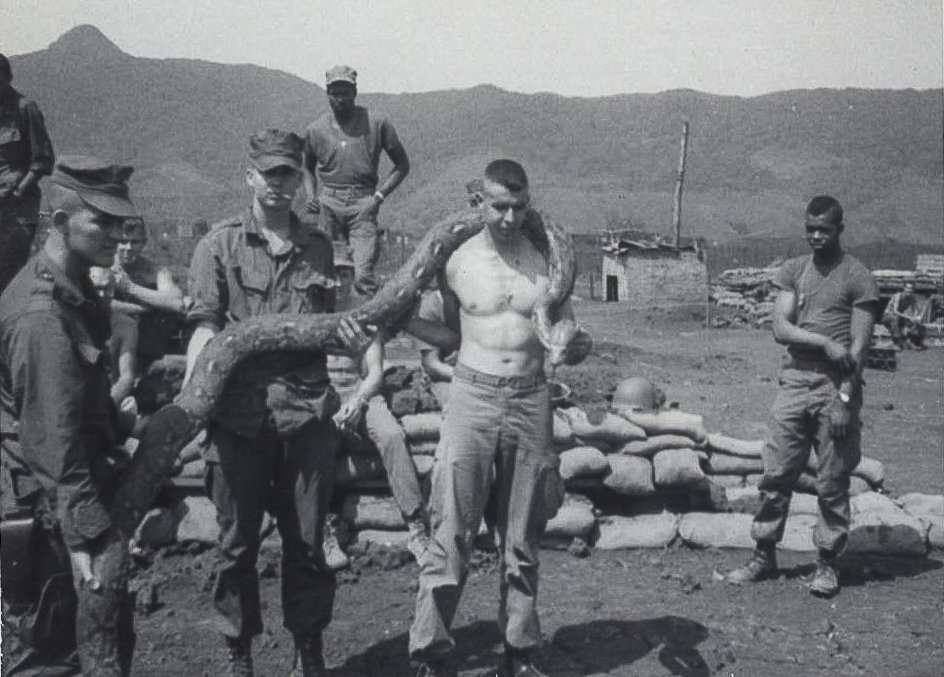

After Operation Doubletalk, Capers was ordered to the Khe Sanh Combat Base — the blood-soaked tip of the spear of north-central Vietnam, where the rest of the 3rd Force Marines had replaced a detachment of exhausted Special Forces soldiers in December 1966. Even by the standards of a brutal conflict, it was hell — a squalid hilltop outpost overlooking a valley through which Vietnamese forces moved supplies to battlefields farther south.

“The bunkers [the Green Berets] left behind were so rat infested, the rats would chew on your ears and nose at night,” wrote Walter Doroski, Broadminded’s point man, in 2008. “[Cpl. Michael] Scanlon was the first to get amoebic dysentery. I dug a hole in the side of the trench to protect him from incoming rounds, slid him in, and fed him when he could eat.”

When Jordan was transferred out of Khe Sanh to a staff position with a higher command in February, the task of coordinating the entire detachment’s patrols fell to Capers. Assaults on the outpost were constant, punctuated by explosions and cries of “Corpsman!” echoing across the valley. The preservation of Khe Sanh depended on Capers’ “raggedy-ass recon teams.” In the jungle, the Marines were clashing daily with a growing enemy force.

Efforts to convey that reality up the chain of command had been fruitless. The American brass, under Gen. William C. Westmoreland, remained undeterred in its stance that activity around Khe Sanh was insignificant. Ten months after Capers’ tenure, the infamous Battle of Khe Sanh — immediately followed by the Tet Offensive — would prove that the size and scope of North Vietnamese Army operations in the area had been tragically miscalculated. But for now, it was all about staying the course.

Unless they were “shot out of the jungle,” the teams of 3rd Force Recon typically spent three to six days on patrol at a time, with little rest in between. In early February, Team Broadminded set out into the jungle, accompanied by a German shepherd named King. They were hunting an NVA platoon in the area. Early in the patrol, King alerted, signaling the enemy was close. Capers figured they were outmanned at least 3 to 1, so he motioned for his men to hold their fire until they could maneuver into a better position.

Within minutes, the dog alerted again, and Capers noticed three NVA soldiers just a few yards away. He opened up on full automatic, dropping all three in a single stroke. Capers’ M16 jammed, but Team Broadminded had already initiated its well-rehearsed contact drill, unleashing a barrage of grenades and bullets as the enemy platoon scrambled. Capers, struggling to unjam his rifle, saw two more NVA soldiers emerge full-tilt in a desperate counterattack. He drew his 9 mm sidearm and gunned them down. Then he ordered his men to finish off what remained of the enemy platoon. When the battle was over, at least 20 NVA soldiers lay dead, their corpses obscured beneath a haze of gunpowder and smoke. From the surrounding vegetation, the screams of the wounded rang out.

On the chopper back to Khe Sanh, the team was subdued.

“There was no backslapping,” Capers recalled. “For us, death and killing had become business as usual.” They’d be back in the jungle in just a few days.

By March of 1967, the surviving Marines of 3rd Force Recon were battle fatigued. For nearly a year, they had moved like ghosts through the jungle, lurking unseen until the time came to engage the enemy. They lived up to the Force Recon motto: swift, silent, deadly. They had killed or wounded hundreds of enemy soldiers, but their legend came at a cost. Roughly three-quarters of the 40 Marines who originally deployed with 3rd Force in April 1966 were killed or wounded.

After months of fierce fighting around Khe Sanh, Capers and his men were transferred back to Phu Bai, a welcome change from Khe Sanh’s daily artillery and rocket attacks. Their minds fixated on surviving the waning weeks of their deployment.

Capers was miserably short-handed. Most of his men were replacements — regular grunts. He had been hearing for weeks that he and his men were going to be relieved by another Force Recon unit, but the missions kept coming without relief. Knowing it was a long shot, but feeling he had to try and save his men, Capers told his battalion commander that unless he got more men, the survivors of 3rd Force should not run any more patrols.

With Westmoreland’s attrition strategy, or “body count,” in full swing, the commander disagreed. Body counts had been deemed the primary metric of success, and you can’t stack bodies if you can’t find an enemy to attack and kill.

In late March, Capers was given orders to locate a suspected North Vietnamese regimental base camp in an area called Phu Loc.

Capers understood the cold reality of the mission to provide observation for the flank of Company M, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines: Broadminded was essentially being asked to serve as bait and flush out the enemy forces so the regular infantry could swoop in for the kind of protracted battle the brass craved. Capers didn’t like the mission, but it was Vietnam — undesirable missions were as ubiquitous as death.

He gathered Broadminded’s core members: Yerman, Capers’ trusted assistant team leader and first radio operator; Sgt. Richard Crepeau, another seasoned sergeant and the team’s second radio operator; and Billy Ray “Doc” Smith, the team’s medical corpsman, and laid out the situation.

“He asked us if we would volunteer to go on our last combat patrol into an almost impossible situation,” recalled Crepeau. “He told us, ‘I’ve been ordered to go, but you don’t have to.’ When your mentor, your boss, your surrogate father asks you to do something, and you’re a Marine, what do you do? You say, ‘Yes, sir.’”

The sergeants and the doc looked at one another. There was no question.

“Where you go, we go,” Crepeau said.

Over the four days the patrol lasted, the team averaged two firefights a day. The terrain was flat, with elephant and beach grass, hedgerows and streams — all of it peppered with seemingly endless tunnels and holes from which enemy fighters would periodically emerge and then melt away.

Broadminded made contact with 20 enemy soldiers on the first day, and an enemy grenade wounded Pfc. Theodore Leach, who had to be evacuated. Capers also took some shrapnel, but the wound was relatively minor.

During another engagement, Capers called for fire on an enemy position, stopping an attack on the grunts they were supporting.

The young infantry force commander who directed the operation kept ordering Capers to take his team down large, open trails, which contradicted their doctrine of stealth. By the fourth day, Broadminded had found four booby-trapped trails — likely ambush sites, a dangerous situation Capers reported to the commander. On the last day of the patrol, however, he was ordered to take his team back the way they’d come. Capers knew it was a grave error and looked to his trusted assistant for input.

“You’ll probably get court-martialed if you don’t do it,” Yerman told him.

As the saying in Vietnam went, There it is. There wasn’t much choice for a junior officer, especially a Black one.

“I knew if I didn’t walk down those trails and locate that base camp, the regular grunts would, and a lot more people might get killed,” Capers said. “I couldn’t live with that.”

Capers gathered his senior team members and asked them again if they would follow him deeper into what seemed, to a degree, a suicide mission. Yerman was the team’s resident psychic, and his prediction before the last patrol had been that all of Broadminded was going down, though he could not say if they would be killed. They understood what was being asked of them and that, years on, if the battle made the history books, the details of how the longest surviving team in 3rd Force Recon was finally wiped out weeks before they were to return home would not play prominently in the narrative, if at all. But the commander who sent them down the trail and the name of his infantry company just might. And there it is, they thought.

The men agreed that Capers wasn’t going into the gauntlet without them.

Broadminded maneuvered slowly and carefully, identifying and withdrawing from three ambush sites. As the team was about to withdraw from a fourth, King, the war dog, alerted, signaling that the enemy was near. Then the nightmare.

A claymore mine is an 8.5-by-3-inch convex slab of inch-deep plastic, packed full of C4 explosives and hundreds of steel balls. It usually sits a few inches above the ground and functions like a giant shotgun shell. Vietnamese fighters had daisy-chained several mines together. Crepeau recalled the moment they detonated like a scene from a film: The five men in front of him were flung to the ground in slow motion. As he watched the shock wave of violence, a steel ball punched through his leg.

At least 15 North Vietnamese soldiers opened fire from two directions with rifles, machine guns, and grenades. Within seconds, nearly every member of the team was badly wounded. The blast knocked Capers against a tree and punctured his body in 14 places from his legs up to his abdomen and back. His right leg was broken, and as he lay severely concussed, he looked over and saw King, limp and lifeless on the bloody jungle floor, his tongue hanging out. The dog had been between Capers and the blast.

Lance Cpl. Harry Nicolaou, a mountain of a man who carried the heavy M60 machine gun with ease, sprayed fire toward the enemy, despite having his right leg nearly blown off at the knee. “Goddamn it, you motherfuckers!” he screamed.

Pfc. Henry Stanton carried the team’s only M79 grenade launcher. He had taken shrapnel all over his legs and in his kidney, and he was bleeding through the mouth and nose when he looked at Capers and said, “Lieutenant, I don’t think we’re going to make it this time.”

“Yeah, we’re going to make it, son. You just hold on there,” Capers said, trying to catch his breath. “Don’t leave me now, Henry. We’re going to make it out of here.”

Stanton began returning fire with his grenade launcher and M14 rifle.

Yerman and Doc Smith were the only members who had relatively minor wounds, but the whole team was fighting for their lives. Yerman crawled over to Capers. “We’re all down, sir!” he yelled. “But we can still fight!”

Enemy grenades were exploding from every direction, piercing the cacophony of screaming voices. Capers ordered Yerman to redistribute the team’s ammo, and his injured men to form a tight security perimeter. Doc Smith, bleeding from his neck and face, sprinted from man to man, treating and dressing their wounds. Soon he got to Capers, who was firing his rifle and throwing grenades as he shouted orders.

“Doc, I’m okay!” Capers barked. “I’m only hit a little. Take care of Nic. I think he caught most of it.”

Smith gave Capers a shot of morphine and then sprinted over to apply a tourniquet to Nicolaou’s leg. As Yerman called for help from the grunts and worked on getting medevac helicopters inbound, Capers told Crepeau to call in mortars on their position. He knew the mortar men would intentionally offset the rounds and Crepeau could call in adjustments until the mortars were falling on the enemy. It was a dangerous gamble, but Capers had no other options.

Soon mortars started tearing through the canopy, and the Marines grunted and cursed as they hugged the earth.

“That’s it. More! Make ’em hurt. They’re not taking us! Move ’em closer!” Crepeau recalled Capers saying.

Capers began to feel dizzy. He had lost a lot of blood, and the morphine added a haze to the whole experience. Eventually, the enemy fire died down, and Capers called off the mortars. The gamble had paid off.

An awful smell hung in the air — acrid smoke and burned flesh and blood and shit. With the grunts en route to help Broadminded to the helicopters, Capers made a short speech.

“We’re getting out of here — all of us,” he told his men. “We’re going to take all of our equipment out, and we’re going to take our dog’s body out. If we have to, we’re going to fight our way out with whatever we’ve got. We’re not going to die on this trail. We’re going home, and we’re going home like Marines.”

After stabilizing everyone, Doc Smith ran to link up with the grunts and lead them to Broadminded’s position. They helped the team down a winding, rain-swept trail toward the helicopter landing zone. Capers used his rifle like a cane and limped along, blood sloshing in his jungle boots. The group took turns carrying King’s body in pairs, grunting and moaning on their way toward their final exit from hell.

Behind them, the grunts from 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines, had found their fight. Capers looked at his men, blood-soaked and hobbling down the trail.

“All I could think about was ‘How could I let this happen?’” Capers recalled. “How in hell could Jim Capers get ambushed?”

Dusk was descending as they approached the extraction point. One H-34 helicopter landed while another circled overhead, providing cover from the remaining enemy forces. The crew chief helped everyone onto the bird. King’s body still lay on the ground.

In a haze, Capers drew his gun. The dog was coming with them, he told the chief, or Capers was staying behind.

The crew chief jumped out and heaved King’s body onto the chopper. Seconds later, the bird lifted about 6 feet, then fell back to earth. “It’s no good,” Capers said, trying to get off the aircraft so it could take off. The crew chief yanked him back in. On the second attempt, the helicopter climbed about 8 feet before falling hard again. Capers repeated his stubborn dance with the crew chief, who again prevented him from getting off the bird. The pilots tried again to take off, the sound of explosions and incoming fire seeming to signal their doom. This time the helicopter rose slowly, clumsily shaking off gravity’s pull before finally lurching forward and climbing toward an ash-colored sky, where lightning flashed in the distance. The sound of thunder and artillery below boomed as the helicopter’s single engine struggled to carry the load.

Capers began to pray. Please God, don’t let my troops die like this. Please don’t let them die in this horrible place. The radio cracked to life as the pilot approached the combat base at Phu Bai. Capers could see the red cross of the field hospital below. Finally, they descended hard on the landing pad, and medical staff rushed them into treatment.

Capers remembered the inside of the field hospital as “a butcher shop.” The doctors had to amputate Nicolaou’s leg below the knee.

Capers looked around the room and felt shame. This is my fault, he thought.

Yerman, 3rd Force’s “psychic Hebrew,” could see the demons vexing Capers, whipping his psyche into a spiral of paralyzing guilt. Yerman believed most officers were self-concerned opportunists who treated war like a game of cowboys and Indians, recklessly throwing bodies into the meat grinder. But Capers was different. He had managed to embody Yerman’s mythic ideal of virtue, and Yerman loved him for that.

Yerman instructed a couple of corpsmen to set his cot next to Capers’. He put his hand on Capers’ arm.

“Hey Lieutenant, this wasn’t your fault,” he told him. “You did a hell of a job. This wasn’t your fault.”

The words just brought more pain.

Soon, Cpl. Walter Doroski arrived at Capers’ bedside and stayed until Capers flew out two days later.

Doroski, the skinny Polish kid whose team members called him the “best point man in Vietnam,” had been the literal tip of Broadminded’s spear on every patrol but the last. He was sidelined with a hernia. Capers and the other NCOs had decided the hernia was reason enough to make Doroski stay behind — to let him survive. He protested vehemently to no avail. So in the patrol’s aftermath, Doroski never left his hero’s bedside, tending to any need Capers had and wallowing in similar feelings of torturous guilt. If only I’d been on point, Doroski thought. The feelings have never left him.

In his statement advocating for Capers’ Medal of Honor, Doroski wrote, “[I’ve] worked overseas in over 30 undeveloped countries on three continents for 25 years. I never found an equal to Lieutenant Capers’ leadership, devotion to his mission and men, or courage in battle.”

Capers recalled the flight back to the US as a lucid nightmare: the screams of young men dying, blood all around, the uniforms of the nurses and corpsmen stained red, Capers’ own gruesomely perforated body. He had a large wound on his abdomen as well as about a dozen other holes up and down his legs. There was a catheter in his penis and another snaking into his arm and a tube in his nose. The near darkness inside the plane’s belly seemed to amplify the screams, which seemed to intensify the excruciating pain. In Capers’ mind, the screams were deafening. If there were ever a situation from which Capers wanted to retreat, it was there in the dark as the audible prayers and anguished cries of the dying ravaged his mind like an errant napalm strike. He was hearing Nicolaou after the claymore, seeing images of his amputated leg. The morphine haze was ever present. After landing in Washington, DC, Capers heard that at least three of the men on the flight had died.

At Bethesda Naval Medical Center, Dottie Capers made her way to her husband’s room on the 14th floor with their 7-year-old son, Gary. Born blind and with special needs, Gary seemed to be looking at Capers when he put his hand on his bed. It warmed Capers’ spirit. In Vietnam, Capers had dreamed of this reunion with his wife, but the bitter sting of shame was all he could feel. Dottie leaned in and welcomed her man home, embracing him in a way that seemed to let him know that she would be the strong one in the months ahead.

When Capers was 15, Dottie staked a claim on his heart when she shot him a fleeting wink on a warm spring day in Baltimore. She was the prettiest thing he’d ever seen. No one else compared. In 1959, Capers asked Dottie if she might like to come with him to Camp Pendleton if he were to reenlist in the Marines. It wasn’t the smoothest of marriage proposals, but Dottie beamed with joy as she accepted.

The doctors told Capers he might never walk again. He had several surgeries, including a major skin graft to close the gaping hole above his right ankle. Soon he was in a body cast, then a wheelchair, then crutches.

For months, Capers rarely got up from his hospital bed. Consumed with remorse and rage, he struggled to reconcile what had happened to him.

Dottie visited Capers as much as possible during his eight months at Bethesda. She endured his constant anger, always trying to understand his incomprehensible transformation. Capers said he became a frail junkie, begging the nurses to break the rule of no more than one morphine shot every four hours. He’d lie there, whimpering and wondering how he had gone from being a proud Force Recon Marine to such a pathetic creature. He was weak, and in his weakness he began to think about how he might get himself over to that window and just “go down 14 floors and be over.”

One day, Dottie picked him up for a drive. She brought him to a parking lot and told him to get out of the car. He struggled from the passenger seat. Then Dottie snatched his cane and walked away.

“You can walk,” she said, “and you’re going to walk to me.” And when she said it, Capers believed her. She was inviting him to his resurrection, and he suddenly knew it was time to start back toward the light. He thought about the man he was before, and he made his agonizing first steps into Dottie’s arms.

A few months later, Capers passed his medical review board, allowing him to stay in the Marines.

He retired as a major in 1978 after a storied career that culminated with his final assignment as commanding officer of 2nd Force Reconnaissance Company. The assignment meant Capers served in all three Force Recon Companies.

He was awarded two Bronze Stars with Valor in Vietnam. Some of his men felt it was inadequate recognition for his battlefield exploits, but if Capers agreed, he kept it to himself.

“I had never even thought about it really,” he said, “because after Phu Loc, I felt like I had failed.”

The Medal of Honor is the only military medal that must be approved by the president on behalf of Congress. When a Marine is recommended for the Medal of Honor based on the first-person accounts of those who personally witnessed his actions, that’s the first and seemingly least important step. Once the nomination package reaches the Pentagon, it then must pass the scrutiny of nearly 20 other people, all with unique opinions about what actions warrant the nation’s highest award for valor.

The system is supposed to ensure the standard set forth in the Department of Defense Manual of Military Decorations and Awards, which stipulates that for the Medal of Honor, there must be “proof beyond a reasonable doubt that the service member performed the valorous action.” It is awarded for “gallantry and intrepidity” at the risk of one’s life “above and beyond the call of duty,” and the act has to be one of “personal bravery or self-sacrifice so conspicuous as to clearly distinguish the individual above his or her comrades.”

As head of the Marine Corps Awards Branch in 2008, retired Col. Lee Freund and his staff reviewed the Medal of Honor package Williams’ staff submitted for Capers and kicked it back, citing a laundry list of administrative and procedural errors. Freund’s advice was that the ambitious, cumulative approach to meeting the award criteria was not going to fly.

Gaskin and Williams regrouped and recast the argument, focusing the recommendation on Capers’ actions during his doomed last patrol in Vietnam. After the Herculean effort was complete, everyone involved waited for news.

In 2010, Capers received a letter from the secretary of the Navy saying he had been awarded the Silver Star, a downgrade of two levels from the Medal of Honor. Capers received no explanation for the downgrade, and many believe it was a miscarriage of justice.

United American Patriots (UAP), the group that’s gained attention in recent years for its advocacy on behalf of military members and veterans charged in criminal cases, is leading efforts to get another review of Capers’ actions for a potential upgrade to the Medal of Honor.

“UAP is working on a request to meet with Gen. Berger, the commandant of the Marine Corps, to learn more about where he stands on the effort to review Maj. Capers’ Medal of Honor,” UAP director of communications Nick Coffman told Coffee or Die Magazine recently. “We’re trying to learn if the decision to downgrade the medal recommendation to a Silver Star was made in accordance with existing standards. If it was, we have no issue with that, but if he was denied due to his race or any other reason, we will work to correct that.”

Capers’ Medal of Honor nomination contained more than a dozen witness statements from the men who served with him and a strong endorsement from his former battalion commander, who personally witnessed Capers’ prowess as a combat leader. Each testified to his unparalleled sense of selflessness on the battlefield and commitment to accomplishing any mission he was given while ensuring the safety of his men. The testimonies say he clearly distinguished himself above his comrades in Vietnam, exhibiting personal bravery and self-sacrifice “above and beyond the call of duty” on a consistent basis.

“He never considered his own life,” Yerman said. “His men were above his own life. None of us had his level of courage. He was ready to give his life for the men in his team at any moment without hesitation.”

When Capers was denied the Medal of Honor in 2010, the military had come under fire from the media and Congress for the marked decrease in the awarding of medals for valor, especially the Medal of Honor. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan constitute the longest conflict in American history, yet they’ve yielded the lowest number of Medals of Honor. An Army Times investigation from March 2009 found that from World War I through Vietnam, the Medal of Honor was awarded at a rate of roughly 25 per 1 million troops. Between the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the medal has been handed out at a rate of 1 per million. When the Army Times published its findings, only five service members had been awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in Iraq or Afghanistan, all of them posthumously. That same year, Congress ordered a review of the Pentagon’s criteria for the Medal of Honor. Today, there are 24 Medal of Honor recipients from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Three of them are Marines, and only two of those Marines survived the actions for which they were awarded.

In 2014, President Obama presented the Medal of Honor to 24 service members from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam who had received lesser awards because of racial discrimination. The numbers were lauded as a victory for the judiciousness of a congressionally mandated Pentagon review that took 12 years to complete. But all 24 of the upgraded medals that resulted from the review came from the Army, which looked at 600 cases for possible upgrades. The other service branches together looked at 275 cases and upgraded no medals.

Gaskin, the general who oversaw the effort to award Capers the Medal of Honor, who has been part of several past Medal of Honor awards boards, said that relative to the Army, the Marine Corps is “very stingy when it comes to awards.” Gaskin said he absolutely believes Capers deserves the Medal of Honor, and he believes part of the reason he didn’t receive it is a cultural resistance within the Marine Corps bureaucracy to acknowledge the institutional racism that once existed.

“Our system is not geared to look back in the past and compare what impact prejudicial treatment would have had on the process,” Gaskin said. “Some officers today cannot comprehend that someone would deny a medal based on skin color. They just cannot fathom today that that actually happened. And I think some officers involved in these processes feel that if they do award these upgrades then they’re acknowledging that the Marine Corps has a stain on it — a stain they’re not willing to acknowledge.”

Doug Sterner, an archivist for the Military Times, has seen similar disputes before.

“It’s a very subjective award that depends very much on how well we tell the story,” he explained.

Freund stands firmly behind the Marine Corps’ award system.

“We charge the commanders endorsing these awards with maintaining our historical ethos,” he said. “Our standards are where they need to be. We don’t cheapen awards.”

[vimeo id=”91033199″ /]

Official notes from a phone interview between Dixon’s superior and Jordan suggest that Jordan’s reservations stemmed from a belief that Capers’ Vietnam service had already been lauded enough.

“Jim Capers, as good as he was, was just one of 40 great men,” he said.

Ultimately, Jordan offered a late, and tepid, endorsement in 2008 — which included a few notes pointing out errors in Dixon’s summary of action.

Jordan insisted that he just wanted to get the facts straight.

“I’d give Jim 16 Medals of Honor if he had the documentation for it,” he said in 2012. “Jim will tell you how close we were. To lose his friendship because of this was and still is very deteriorating for me.”

The men reconciled at a 3rd Force reunion years later.

Williams, who retired as a major general in 2010, said the Marines’ elite culture, usually a point of pride, has evolved awards standards so high they’ve undermined the credibility of the system.

“The Marine Corps is the absolute worst in terms of recognizing our men and women for everything they do,” he said. “And it’s not about the ribbon; it’s about the recognition that somebody cared to give a damn about what you did.”

Williams said Capers’ story is one of many cases in which the Marine Corps awards system has failed. He believes the most important function of military medals is to administer to the spiritual and mental health of those who serve in combat, an assertion supported by the research of Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, a former psychology professor at West Point who has trained thousands of Marines on combat’s psychological toll. Grossman is the author of On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning To Kill in War and Society, and he said the awarding of medals and decorations is a vital component of the process by which service members cope with their combat experiences.

“The honors and decorations that are traditionally heaped upon military leaders at all levels are vitally important for their mental health in the years that follow,” Grossman wrote in On Killing. “These decorations, medals, mentions in dispatches, and other forms of recognition represent a powerful affirmation from the leader’s society, telling him that he did well, he did the right thing, and no one blames him for the lives lost in doing his duty.”

The lost detachment project was supposed to be a source of pride — an ultimate validation of Capers’ legacy. Instead, it became a source of great anguish. A year after receiving news of the medal downgrade, Capers was still struggling to deal with his bitter frustration when his health began to fail. He ended up in the hospital, and the doctors feared he would not survive. Then Lt. Gen. Ronald L. Bailey, who was stationed 90 miles south at Camp Pendleton, was a close friend and refused to accept the doctors’ prognosis. He made arrangements to move Capers to San Diego for treatment.

As Capers’ recovery progressed, Bailey moved him into his home on Camp Pendleton. When Capers was strong enough, Bailey found him an apartment in nearby Oceanside, where Dixon eventually became Capers’ spiritual anchor.

Dixon was well acquainted with the demons of post-traumatic stress that had returned to haunt Capers, and he was determined to help tell Capers’ story to the world — to right the wrong he believed had been done.

Dixon convinced Capers to continue pushing for recognition. By then, Capers was alone. His role as a devoted husband and father were central to his spiritual health in a way he had taken for granted until tragedy struck again. His son, Gary, had died in 2003 from a misdiagnosed ruptured appendix (Capers was awarded a settlement). Capers and Dottie leaned on each other to cope with the loss. Then, in 2009, as Capers awaited news on the Medal of Honor, Dottie passed away from cancer.

With his family gone, Capers needed a mission, and Dixon provided one. The men spent months together, living in the apartment in California, drafting petitions, working on Capers’ memoir and treating their post-traumatic stress as best they knew how. In many ways, they were two battle-scarred Marines on the last patrol of their lives.

In February 2012, Dixon went to visit his family in Baxley, Georgia. On Feb. 19, he had a mental breakdown, and around 3:50 a.m. that day, Dixon’s neighbors called the Appling County Sheriff’s Office to say someone had fired shots at their property. Roughly five hours later, Dixon made his phone call to Capers before walking outside of his house, where members of the Georgia State Patrol’s SWAT team ordered him to put down his shotgun and then shot and killed him when he didn’t. He was 30.

Dixon’s death was another devastating blow to Capers’ mental health. When Dixon died, Gen. Bailey accompanied Capers to the funeral. They joined Dixon’s friends and family and dozens of other Marines for the ceremony in Baxley. It drew full military honors and a contingent of Patriot Guard Riders. Dixon’s father, who served as a Marine in Vietnam, wanted his son buried in uniform, so Capers paid for a set of dress blues. At Capers’ request, the general presented Capers’ Silver Star to Dixon’s parents, asking that their son be buried with it. Although he hadn’t planned to speak, Capers was overcome with emotion and wanted to tell everyone gathered what Dixon meant to him. He told them about all the loss in his life, how he’d lost his own son, and how Dixon had stepped in and become Capers’ family when he needed one so badly. Capers told them about how Dixon “got it,” how he understood that you never give up when you’re fighting for what is right.

When Capers returned to California, he found himself alone once again — an old, arthritic warrior with shrapnel in his bones and a headful of hard memories.

“I’d lost everything important to me,” Capers said. “I guess I bought into the idea that the award was bigger than me because I needed to.”

Capers moved back to Jacksonville, where he lives a quiet life. He published Faith Through the Storm: Memoirs of Major James Capers, Jr. in 2018, and Major Capers: The Legend of Team Broadminded is a documentary about his life.

Last summer, he traveled to Bishopville, South Carolina — the small town where he lived as a young boy. Citizens and supporters filled the streets for a special celebration and unveiling of a massive plaque to honor Capers. On a wall in the town’s Memorial Park, a metal map of North and South Vietnam and a summary of his extraordinary life flank a bas-relief sculpture of Capers’ iconic ASK A MARINE poster under the words “The Place, The Legend, The Man.”

Filled with emotion, Capers told the crowd humbly, “I don’t deserve any of this. It really doesn’t belong to me, I’m just a caretaker.”

The event seemed to galvanize Capers supporters, and it helped reignite the effort to see him recognized with the military’s highest honor.

“There’s still a failure to recognize a piece of history here,” Williams said. “The fight isn’t over.”

If United American Patriots’ efforts to have Capers’ Silver Star upgraded to the Medal of Honor fail, the UAP’s Coffman said, the organization plans to lobby for Capers to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

“We feel very strongly that Major Capers’ actions warrant the Medal of Honor,” he said. “There is bipartisan support for this effort in Congress, and we will continue to work with all who are willing to join our efforts.”

[vimeo id=”91033349″ /]

Ethan E. Rocke is a contributor and former senior editor for Coffee or Die Magazine, a New York Times bestselling author, and award-winning photographer and filmmaker. He is a veteran of the US Army and Marine Corps. His work has been published in Maxim Magazine, American Legion Magazine, and many others. He is co-author of The Last Punisher: A SEAL Team THREE Sniper’s True Account of the Battle of Ramadi.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.