Chuck Yeager, Pioneering Air Force Test Pilot Who First Broke the ‘Sound Barrier,’ Dies at 97

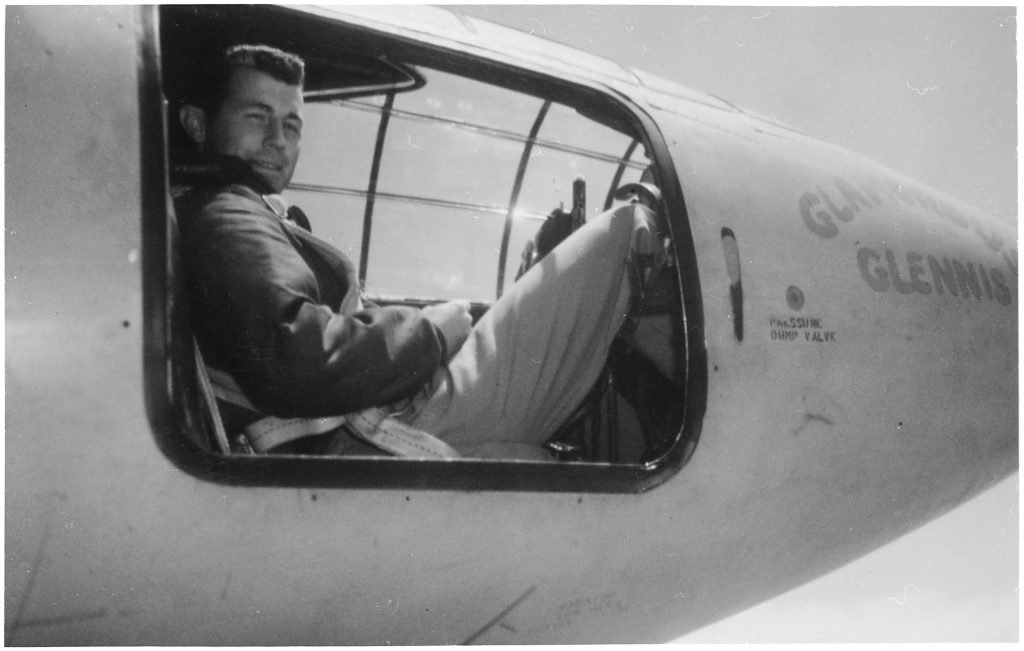

Retired Brig. Gen. Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager prepares to board an F-15D Eagle from the 65th Aggressor Squadron Oct. 14, 2012, at Nellis Air Force Base, Nev. In a jet piloted by Capt. David Vincent, 65th AGRS pilot, Yeager is commemorating the 65th anniversary of his historic breaking of the sound barrier flight Oct. 14, 1947, in the Bell XS-1 rocket research plane, named “Glamorous Glennis.” Yeager was awarded the prestigious Collier Trophy for his landmark aeronautical achievement. U.S. Air Force photo by Master Sgt. Jason Edwards via DVIDS.

Most armchair aviators probably think there’s no more iconic cinematic portrayal of the daredevil pilot ideal than that of Tom Cruise’s Maverick in the 1986 film Top Gun. Truth be told, however, in the eyes of many American military pilots another iconic movie scene best epitomizes the fabled “right stuff” — that magical, practically indefinable quality of calm coolness displayed by the very finest pilots in the face of extreme danger.

That scene comes at the end of the 1983 movie, The Right Stuff. Based on Tom Wolfe’s 1979 book, the movie tells the story of America’s original seven astronauts, as well as the hard-charging exploits of Charles “Chuck” Yeager — the iconic US Air Force test pilot who became the first human to fly faster than the speed of sound in October 1947, and who was “the most righteous of all the possessors of the right stuff,” Wolfe wrote.

Chuck Yeager died on Monday at the age of 97, according to a statement posted by his wife, Victoria Yeager, on Twitter. The Associated Press also confirmed his death.

Fr @VictoriaYeage11 It is w/ profound sorrow, I must tell you that my life love General Chuck Yeager passed just before 9pm ET. An incredible life well lived, America’s greatest Pilot, & a legacy of strength, adventure, & patriotism will be remembered forever.

— Chuck Yeager (@GenChuckYeager) December 8, 2020

The Right Stuff film closes with Yeager, played by Sam Shepard, parading away from the smoldering wreckage of his F-104 Starfighter. Moments earlier, Yeager had narrowly ejected after taking the sleek, single-engine, supersonic fighter to the limits of the atmosphere. With Bill Conti’s triumphant score thundering in the background, and framed by the billowing black smoke of his wrecked aircraft, Yeager struts across the parched, sun-cracked expanse of the open desert. His hair is matted with sweat. His face is burnt and bloody. He holds a folded parachute in one hand, his helmet in the other. Chin held high, still chewing his Beemans gum. He walks tall and strong. Unbroken. Like a medieval knight nobly striding away from a quieted battlefield. Victorious.

Yeah, that’s the stuff.

Save your fist-pumping Tom Cruise on a motorcycle for someone else. As for me — as I suspect is the case among most American military pilots, current and former — an electric chill ripples down my spine when I imagine Chuck Yeager in that iconic scene from The Right Stuff. That movie moment, incidentally, was drawn from a real-life 1963 crash in the Mojave Desert, in which Yeager’s out-of-control aircraft was “spinning down like a record on a turntable,” he later wrote.

After ejecting, Yeager became tangled in his parachute lines and scorching hot debris came in through the broken face shield of his helmet, leaving him with severe burns. “My face was charred meat,” he later wrote in his 1985 memoir, Yeager.

Yeager. That name instantly evokes the image of the 24-year-old pilot smiling in front of his Bell X-1 rocket plane.

Yeager. That soft-spoken, horseback-riding, whiskey-drinking warrior who rode his mounts of fire-spewing steel into single combat against the faceless “demon” who lived on the other side of Mach 1 — the “sound barrier.” Eternally unflappable. Eternally cool. No matter what mortal perils he faced. Egotistical? Yeah, maybe. But if Yeager didn’t deserve a little ego, then who the hell does?

Yeager. The West Virginia native who liked “huntin’ and fishin’” — with his terse backcountry drawl (which has defined the unhurried and unexcited enunciation of airline pilots for generations), and that singular emotional aloofness that bespeaks his airborne exceptionalism. The kind of exceptionalism every pilot aspires to achieve. To be “good.” To be a “natural.” And — as camp as the expression may have become since its inception in Wolfe’s eponymous book — to possess “the right stuff.”

“I was incredibly sad to hear of the passing of Chuck Yeager,” said Rick “Cage” Kernea, a former Air Force F-15C fighter pilot and instructor pilot in the T-38C Talon, the supersonic jet flown by future Air Force fighter and bomber pilots in training.

(In the interest of full disclosure, Kernea was one of this correspondent’s pilot training instructors.)

“His legacy was one that inspired me to seek professional excellence in my flying career — and to instill that same desire to achieve in the next generation of fighter pilots that I was honored to instruct. Blue skies General Yeager,” Kernea told Coffee or Die Magazine.

The legend of Chuck Yeager is most intrinsically linked to his historic October 1947 flight in the Bell X-1 rocket plane — named “Glamorous Glennis” after his first wife — in which he became the first human to fly faster than the speed of sound.

For some 18 glorious seconds, Yeager piloted the bright-orange, bullet-shaped X-1 faster than Mach 1, climbing some 8 miles above Southern California’s Muroc Field — later known as Edwards Air Force Base, the mecca of Air Force test pilots.

News of the milestone achievement was kept secret until 1948. Today, it’s the stuff of legends. Consider this — two days before that famous flight, Yeager was thrown from a horse and broke two ribs. He kept his injuries under wraps from the flight doctors — those stubborn spoilers of dreams and derring-do. Yet, there was a problem. Yeager’s broken ribs would prevent him from leaning over to close the X-1’s hatch. So, the young pilot improvised a solution: He took a sawed-off broom handle into the rocket plane’s cramped cockpit to close the latch from his lame side.

With the door secured, the X-1 was dropped from the belly of a B-29 bomber at an altitude of 23,000 feet before rocketing up to a speed of some 700 miles per hour — Mach 1.04 — and an altitude of 43,000 feet.

History was made. And Yeager’s name would live forever.

For years, Yeager continued to push the envelope of experimental high-speed flight — staying on top of the pyramid as the “fastest man alive.” In March 1948, Yeager flew the X-1 to a speed of Mach 1.45 — 957 miles per hour — reaching an altitude of 71,900 feet. It was the highest and fastest a human had ever flown.

Five years after his historic first X-1 supersonic flight, Yeager flew to Mach 2.44 in the X-1A — more than twice the speed of sound — setting a new speed record in the process. After reaching top speed, the X-1A (an upgraded version of the X-1) began spinning out of control. He was thrown about within the cockpit by the violent forces that reached eight times the normal pull of gravity, and his helmet cracked the aircraft’s plastic canopy. Yet, true to form, Yeager kept his cool, recovered from the inverted spin, and piloted his stricken aircraft to an uneventful landing.

Reportedly disqualified from NASA’s astronaut program due to his lack of a college degree, Yeager never flew in space. And, according to the accounts of some other military aviators who matriculated through the Air Force’s test pilot program to join NASA, Yeager sometimes heaped scorn on those who abandoned test-flying airplanes for riding automated spacecraft into outer space.

He also didn’t shy away from touting his own stick-and-rudder skills.

“I don’t deny that I was damned good,” Yeager wrote in his 1985 memoir. “If there’s such a thing as ‘the best,’ I was at least one of the title contenders.”

Despite never surpassing the limits of earth’s atmosphere, the breadth of Yeager’s career invaluably contributed to many of the advances in aerospace technology needed for America’s manned spaceflight program, as well as the development of multiple generations of advanced military aircraft.

“Gen. Yeager’s pioneering and innovative spirit advanced America’s abilities in the sky and set our nation’s dreams soaring into the jet age and the space age,” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said in a Tuesday statement, adding: “[H]is achievements rival any of our greatest firsts in space.”

Yeager’s aerial exploits far exceeded his pursuit of that “demon” living on the other side of some Mach number.

By the end of World War II, when he was just 22, Yeager had scored 12.5 kills, according to the Air Force Flight Test Center History Office. You only need five kills to be an ace. In fact, he shot down five German Messerschmitt-109 fighters in one day in October 1944. And on Nov. 6, 1944, Yeager shot down a German Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighter that was on final approach for landing — logging one of the first-ever air-to-air kills of a jet.

“The first time I ever saw a jet, I shot it down,” Yeager famously said.

In November 1944 he shot down four more German planes during a single mission.

“That day was a fighter pilot’s dream. In the midst of a wild sky, I knew that dogfighting was what I was born to do,” Yeager later said.

Born in 1923, Yeager grew up in West Virginia. After the outbreak of World War II, he joined the Army Air Corps in 1941. He started off as a mechanic and worked his way up to earning his wings as a fighter pilot by 1943. On March 5, 1944, while on only his eighth combat mission as a P-51 Mustang pilot, Yeager was shot down over Nazi-occupied France. He immediately linked up with the French Resistance and evaded capture. With the help of French partisans, and despite a harrowing skirmish with Nazi troops, Yeager escaped to the South of France and then crossed the Pyrenees Mountains into Spain. He successfully reached the British redoubt of Gibraltar on May 15 after more than two months on the run. A week later he was back in England where he personally petitioned Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower for permission to return to flight status.

Yeager ultimately flew 64 combat missions in World War II.

After the war, Yeager married Glennis Faye Dickhouse — the namesake of his legendary X-1 rocket plane, which one can now find hanging from the rafters of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum on the Washington Mall.

Over the span of his flying career — which led him from heading the test pilot program at Edwards Air Force Base to commanding a fighter squadron in West Germany in 1955 — Yeager also commanded a fighter wing during the Vietnam War as a colonel. He flew 127 missions in that war, mainly in B-57 light bombers attacking enemy troops and supplies along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, according to Air Force Air Combat Command. He ultimately rose to the rank of Air Force brigadier general and retired in 1975.

After his wife’s death in 1990, Yeager remarried and reportedly lived in northern California.

Today, in the dormitory halls of the US Air Force Academy, you’re likely to find an ad hoc likeness of Yeager painted on the walls. He remains THE ideal of the Air Force pilot. Might be a long time before there’s another like him. If there ever will be.

In the opening sequence of The Right Stuff film, the narrator describes the brave pilots of Yeager’s generation who repeatedly risked death in pursuit of flying the X-1 past the “sound barrier.”

“They were called test pilots, and no one knew their names,” the narrator intones.

Well, it’s not likely that we will ever forget the name Chuck Yeager.

Godspeed, Chuck. And in the words of the fourth verse of the Air Force Song:

Here’s a toast to the host

Of those who love the vastness of the sky,

To a friend we send a message of the brave who serve on high.

We drink to those who gave their all of old

Then down we roar to score the rainbow’s pot of gold.

A toast to the host of those we boast, the US Air Force!

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.