Hitting Her Mark: Army Veteran Lia Coryell’s Path to the Paralympics

Army veteran and Paralympic archer Lia Coryell prepares to release her arrow during the Veteran Adaptive Athlete Shoot on April 15, 2021, near San Antonio, Texas. Photo by Hannah Ray Lambert/Coffee or Die Magazine.

Lia Coryell’s eyes fluttered open on a spring morning in 2014. As she stirred and moved to get out of bed, she was struck by panic at the realization her legs would not work. She’d felt lethargic for a while, but this was new. Overnight, she had completely lost the ability to walk.

Doctors gave Coryell a wheelchair and put her on palliative care, informing her that her multiple sclerosis had become progressive. It was never going to improve. Tomorrow would never be better than today.

For months, Coryell simply tried to stay alive. She quit her job, stopped going anywhere, and, as she puts it, got “fat and sad and lonely.”

“It sucks — living, trying not to die,” she says.

In taking her ability to walk, life had dealt yet another blow to Coryell, an Army vet and single mom whose rough childhood had set the tone for a life beset with challenges but defined by perseverance. She now had a new opportunity to pick herself up, emerge as a champion archer, and prove just how far rebels can rise.

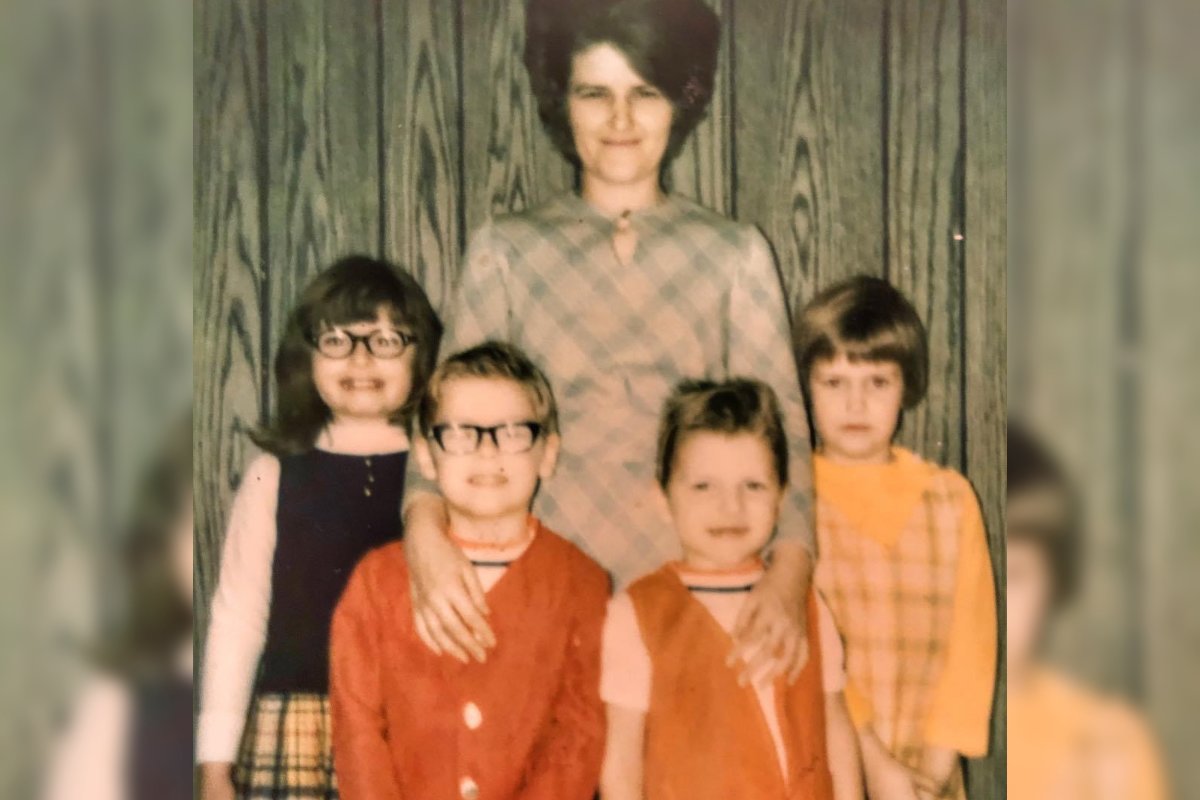

As a teen in La Crosse, Wisconsin, Coryell saw the Army as an escape from the poverty, domestic violence, and dysfunction she and her eight siblings were born into.

“I’ve had short hair my entire life because we had lice all the time,” Coryell told Coffee or Die Magazine, her now chin-length gray curls pulled back at the crown of her head.

As she was growing up, Coryell’s teachers wrote her off. She couldn’t check out books from the library because administrators believed she’d steal them. During gym class, she had to sit with her nose against the wall because she only had saddle shoes. At lunch, she faced the wall again, waiting for the kids who got sent to school with lunch money to eat first.

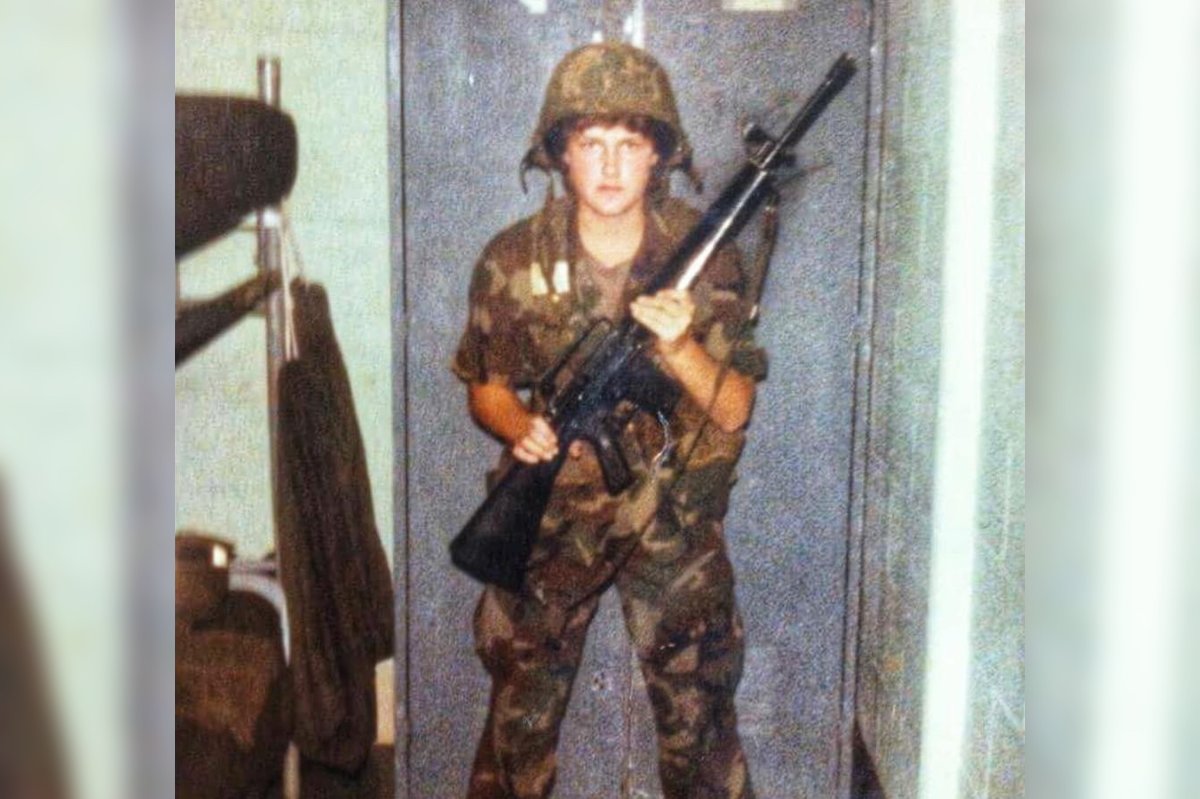

In hopes of securing a better future, Coryell enlisted in the Army her senior year of high school. Her family tree traces its military roots back to Coryell’s Ferry, where Gen. George Washington’s troops crossed the Delaware River in June 1778 on the way to the Battle of Monmouth. Women in the family had never been part of that patriotic history. She wanted to change that.

“I’m just a rebellious person,” Coryell says. “All the things people thought I couldn’t achieve — that’s what drives me. I want to show people you don’t have to stay where you started.”

The Army was a lifeline — a vast improvement from Coryell’s hardscrabble upbringing. Breaking her leg during a training exercise in 1983 shouldn’t have been a service-ending injury, but unexplained nerve damage, a fever, and blurred vision followed. After serving just over a year on active duty at Fort Dix, Coryell was medically retired at 19. She was crushed, but she charged ahead.

Two years later, doctors diagnosed her with MS. Hit with another major setback, she carried on. She earned four degrees: physical education and health, recreation, education, and research and library science. She got married, had two kids, and divorced, raising her children primarily by herself. Always a fan of the outdoors, Coryell took her son and daughter hiking, fishing, and kayaking on a regular basis. She taught high schoolers and helped found a chapter of Student Veterans of America at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her life was full. Happy.

Until that morning in 2014 when she found she could no longer walk. She sat at home for months, gaining weight and losing her spark, until her son — then a teenager — gave her a heart-to-heart that finally broke the spell.

“‘Mom, you’re going to die anyway. We all are,’” she remembers him saying. “You might as well do what you want and make your mark on the world before that happens.”

That September, the student veterans in Coryell’s group were invited to an adaptive sports clinic in California. They begged her to go with them. As a 50-year-old woman who had never played any sports, Coryell gave track and field, wheelchair basketball, and most other activities a hard pass.

Then she saw the archery course.

“I’ve never shot a bow standing up. I have no idea what that would feel like,” Coryell says.

She did all right her first time shooting a bow, but her disability level caught the eyes of recruiters for the US Paralympic Archery Team. Coryell is the only female W1 archer in the Western Hemisphere, meaning she has impairment in both her arms and legs and competes from a wheelchair.

“I was recruited because I’m the most fucked up,” Coryell says matter-of-factly. “At first I’m like, ‘Fuck it. I’m not doing this … I don’t want to be the token broken.’”

But a recruiter triggered Coryell’s inner rebel when she pointed out that she could change the way people look at women and impaired athletes.

In 2015, Coryell qualified for Team USA. Within about a year of starting training, she competed in the World Archery Para Championships, the Parapan American Championships, and the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games.

“It’s very characteristic of her to put her mind to something and excel quickly,” says Joe Multhauf, Coryell’s son and an Army veteran and archer who took up the sport as a kid.

Finding a new sense of purpose made Coryell more upbeat and outgoing — a night-and-day difference from when doctors told her she was dying.

“As my health gets worse, I continue to break records,” she says, eyes bright with excitement. “I continue to shoot higher scores. How does that even work? It’s because I believe I can.”

Archery provided the opportunity to prove the world wrong and help other rebels do the same. She’s been able to connect with and inspire children with disabilities, and last summer, she coached in the background as Army veteran Jonathan Lopez, whose arm was amputated after a drunk driver hit him, taught 8-year-old Honey, who was born with a brachial plexus injury, to shoot using a mouth tab. Video of the pair shooting went viral, and Coryell was flooded with responses from parents, including a mother who said the video sparked tears of remorse. She had pulled her son, who was born without a hand, out of Cub Scouts because they had an archery unit. She’d thought he wouldn’t be able to participate.

Honey, meanwhile, advanced to where she needed a bigger bow. Coryell brought her one but with a caveat: Honey had to pass her old one on to another little boy or girl who needed one. She sent it to the boy without a hand.

“That’s the power of social media,” Coryell says. “My coach told me five years ago, ‘This is your opportunity.’ She wasn’t wrong.”

Archery introduced Coryell to other athletes who hold themselves and their teammates to high standards.

At a competition in Oklahoma not long after she’d gotten her chair, she wasn’t shooting well enough to meet fellow Team USA archer Eric Burkett’s standards. The Marine Corps veteran first picked up a bow in his late teens but hit his stride competitively after a 2012 Osprey crash damaged his legs, resulting in two amputations in the following years.

By the time he met Coryell, he was a self-described sophomoric, cocky archer with a little bit of talent.

“And then here’s Lia, brand-new to the sport. Her shit’s in the street,” he told Coffee or Die.

Burkett wasn’t the only guy on her team frustrated that they had to slow everything down for the “old lady,” Coryell says, but he was the snarkiest, busting her balls at every opportunity.

After the tournament, Burkett went home, letting the encounter slip from his mind until a package showed up in the mail. He unwrapped it to reveal a coffee mug, printed with the image of Oscar the Grouch from Sesame Street.

“I’m like, ‘What the hell is this? Who sent me this? Whatever. It is a nice big coffee mug,’” he remembers thinking.

A few weeks later, an Oscar the Grouch T-shirt arrived. The anonymous gifts continued for a year until understanding finally dawned on Burkett, and he wondered if he’d really been such a jerk.

“Really, I kind of was,” he says.

Now, Coryell describes Burkett as her biggest cheerleader, and he calls her the big sister he never wanted. When the injuries from the Osprey crash proved too much and he had to have his second leg amputated in 2018, she sent him T-shirts again, this time printed with reminders not to skip leg day.

The gag horrified outsiders. She could not send those to a man who just lost his leg, they told her. Coryell says she’s a firm believer that you can either laugh or cry in the face of adversity. Burkett proudly wore the shirts to physical therapy, occupational therapy, and everywhere in between.

“She’s been more than just a teammate of mine,” he says. “If there’s any kind of drama or anything else, she’s one of the very first people I talk to about it because she’s very levelheaded, and she often sees situations much differently than I do. So I really value her opinion and her friendship.”

Coryell was set to go to Tokyo for the 2020 Games, but then the world went into lockdown. Since MS put her at a higher risk for COVID-19, she was initially terrified to go anywhere. Nobody, not even family, came to her apartment, and Coryell — normally a social butterfly — never left.

“It’s only social distancing if you live with other people,” she says. “If you live alone, it’s solitary confinement.”

After about six weeks, she developed pericarditis, an infection around the lining of the heart. Coryell says it can be triggered by stress for immunocompromised people.

The infection cleared up, and she spent much of the summer practicing outdoors. Then on Nov. 6, she tested positive for coronavirus. After battling COVID for a couple of weeks, she left the hospital feeling better. Three days later, she could barely breathe and wound up back in the hospital with bacterial pneumonia. Heart failure, the early stages of kidney failure, and a staph infection followed.

“I fought for my life for 10 weeks,” she says. “I seriously didn’t know if I was going to live or die.”

Coryell felt ready to give up, but her kids told her she had to fight harder. So she did.

In January, she was cleared to start practicing again, and in March, she won gold at the Pan American Championships. Her scores weren’t stellar, but that didn’t matter.

“It was extremely emotional for me because it was the first time I’d ever won an international gold medal,” she says. “They frickin’ put the flag up and played the national anthem for me.”

Coryell knows Tokyo will likely be her last Paralympics as an athlete. She’ll probably never meet her grandchildren. But the woman who entered the world under “really shitty circumstances” hopes to leave the earth better than she found it.

She often thinks about her legacy and the people she’s met and encouraged. She thinks of the parents who send her messages from all over the world, offering thanks or asking for advice on helping their children learn adaptive archery. She thinks of the little boy who saw her at an archery range and stopped in his tracks, saying he’d never seen anyone who used a wheelchair like him shoot a real bow and arrow.

“That’s where I live,” Coryell says. “This is just a body. That’s where my legacy is.”

This article first appeared in the Summer 2021 edition of Coffee or Die’s print magazine as “The Incredible Lia Coryell: Army Vet and Paralympic Archer Hits Her Mark.”

Read Next:

Hannah Ray Lambert is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die who previously covered everything from murder trials to high school trap shooting teams. She spent several months getting tear gassed during the 2020-2021 civil unrest in Portland, Oregon. When she’s not working, Hannah enjoys hiking, reading, and talking about authors and books on her podcast Between Lewis and Lovecraft.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.