How The British ‘Libyan Desert Taxi Service’ Committed Desert Piracy During World War II

A heavily armed SAS jeep in the desert in 1943. The SAS relied on the “Libyan Desert Taxi Service” to “show the way” during long-range reconnaissance patrols across North Africa. Photo courtesy of the National Army Museum.

North Africa’s Great Sand Sea served as a secret highway into Italian territory, and British Maj. Ralph A. Bagnold knew it. During the 1920s and 1930s, the World War I veteran and sapper officer had acquired expertise exploring the unmapped desert frontier between Egypt and Libya.

When Italy declared war on France and the United Kingdom in June 1940, British forces in Egypt were desperate for actionable intelligence on Italian military garrisons in Libya, Eritrea, and Abyssinia (now called Ethiopia). It was believed an attack against the British was imminent — but Bagnold had a plan.

“We had absolutely no contacts with the place, 700 miles away across the dunes and waterless desert, and no suitable aircraft that could do the double range,” Bagnold wrote, according to the Imperial War Museums’ Book of War Behind Enemy Lines. “The only solution was to drive into inner Libya and find out.”

On June 23, 1940, Bagnold, then 44, met with Gen. Archibald Wavell, the commander in chief of British forces in the Middle East, and proposed his plan for a mobile ground scouting force. According to Bagnold’s plan, the so-called Long Range Desert Group, or LRDG, would commit “piracy on the high desert” and acquire the intelligence British forces needed for combat in North Africa. Wavell didn’t have a better option, so he gave Bagnold six weeks to stand up a crack reconnaissance unit from scratch.

“Never in our peacetime travels had we imagined that war could ever reach the enormous empty solitudes of the inner desert, walled off by sheer distance, lack of water, and impassable seas of sand dunes,” Bagnold wrote in 1945.

He continued, “Little did we dream that any of the special equipment and techniques we had evolved for very long-distance travel, and for navigation, would ever be put to serious use. I may add without unfair criticism, that the army authorities shared in this lack of second sight. In peacetime our troops had never trained for a desert war, as officially we were never going to be at war with Italy.”

The unit’s first volunteers were enticed by a bulletin requesting men “who do not mind a hard life, scanty food, little water, lots of discomfort, and possess stamina and initiative.”

Bagnold searched for men “who knew how to look after things and maintain things.” He first drew recruits from the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force, which included many farmers within its ranks. But as the upstart reconnaissance unit grew in size, Bagnold recruited soldiers from all Commonwealth forces, including those of the UK, Australia, India, Rhodesia, and South Africa.

Early on, the outfit was organized into three patrols — R, T, and W — each of which comprised two officers and 30 troops. The troopers had specific job assignments — there were drivers, navigators, wireless operators, and fitters (mechanics).

The other groups were Yeomanry (Y), Guards (G), and South Rhodesians (S). The patrols traveled in convoys of 11 desert-adapted vehicles equipped with Lewis machine guns, Boys anti-tank rifles, a 37 mm Bofors light anti-tank gun, and various small arms. These specially adapted gun trucks had their windshields, doors, and other unnecessary parts removed to make room for up to two tons of supplies, gear, and ammunition. The patrols were able to operate without support for about three weeks.

Bagnold’s prior desert expertise was priceless to the unit’s success. In 1932, he had led the first recorded motorized east-to-west crossing of the Libyan desert — once thought to be an impassable barrier of sand dunes for motor vehicles — in a Model A Ford equipped with a navigational sun-compass. He had adapted specific modifications and techniques for desert travel, which the entire outfit then adopted in their operations. Those techniques included driving with reduced tire pressures over loose sand and at speed over sand dunes. These methods soon became the unit’s standard operating procedures.

Bagnold also developed an innovative way of preserving water. He connected engine overflow pipes to cans of half-full water on the fronts of vehicles in order for the boiling water to condense inside the cans. When a vehicle’s can of water started to boil over, the driver would swerve the vehicle into the wind, and all the water would be sucked back into the radiator, filling it again. Bagnold also invented a new compass design that revolutionized desert travel.

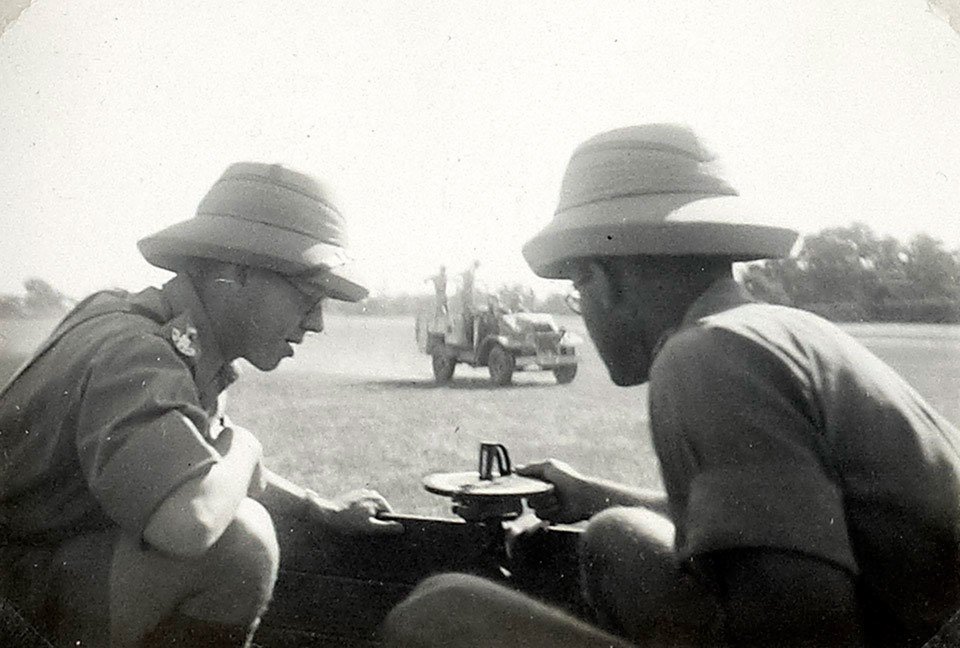

“The compass we used was invented by Bagnold, and the advantage that it gave us over the sun-compasses used by the rest of the Army lay in the fact that it showed the true bearing of the course followed at any moment, whereas the other types only made certain that if the sun’s shadow fell on the correct time-graduation the truck was following a set course,” Maj. Gen. David Lloyd Owen, a veteran of the LRDG, said.

Owen continued, “This meant that if one had to change course for any reason (and this happened all the time in rough country or sand dunes), the truck had to be halted and the compass set again. This was all very time consuming, and I have never understood why the Army did not adopt the Bagnold sun-compass, which was far simpler to operate, absolutely ‘soldier-proof’ and, I would have thought, cheaper to produce.”

In a span of just five months, the LRDG had developed an impressive reputation. “Operating in small independent columns, the group has penetrated into nearly every part of desert Libya, an area comparable in size with that of India,” Wavell wrote in October 1941, according to the Imperial War Museums’ Book of War Behind Enemy Lines.

“Not only have patrols brought back much information,” Wavell wrote, “but they have attacked enemy forts, captured personnel, transport and grounded aircraft as far as 800 miles inside hostile territory.”

Until the end of World War II, the LRDG carried out more than 200 special-operations missions behind enemy lines — from the deserts of North Africa to the islands of the Aegean Sea, to the mountains of the Balkans.

The masters of desert navigation assisted other units, too, including the Libyan Arab Force, the Free French, the Sudan Defense Force, and the legendary Special Air Service. In tandem with their missions, the LRDG guided these units to their objectives. In some instances, LRDG members inserted supplies to clandestine units. They also rescued downed airmen and prisoners of war.

After achieving enormous success during the war, Bagnold’s unit earned its nickname, the “Libyan Desert Taxi Service.” The LRDG’s post-war legacy proved critical in advancing the lineage of the SAS into the lethal force it is today.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.