Our Revolutionary War on Smallpox: Lockdowns and Mass Inoculations

“Washington’s Entry Into New York/ On the Evacuation of the City…1783.” Before Washington could defeat the British, his troops had to overcome smallpox. An 1857 Currier & Ives lithograph, now in the National Museum of American History, thanks to a gift from Salvatore and Mary Winifred Cilella.

Many Americans of the founding era denounced government tyranny, celebrated the Declaration of Independence – and favored lockdowns and mass inoculations to combat a viciously contagious disease.

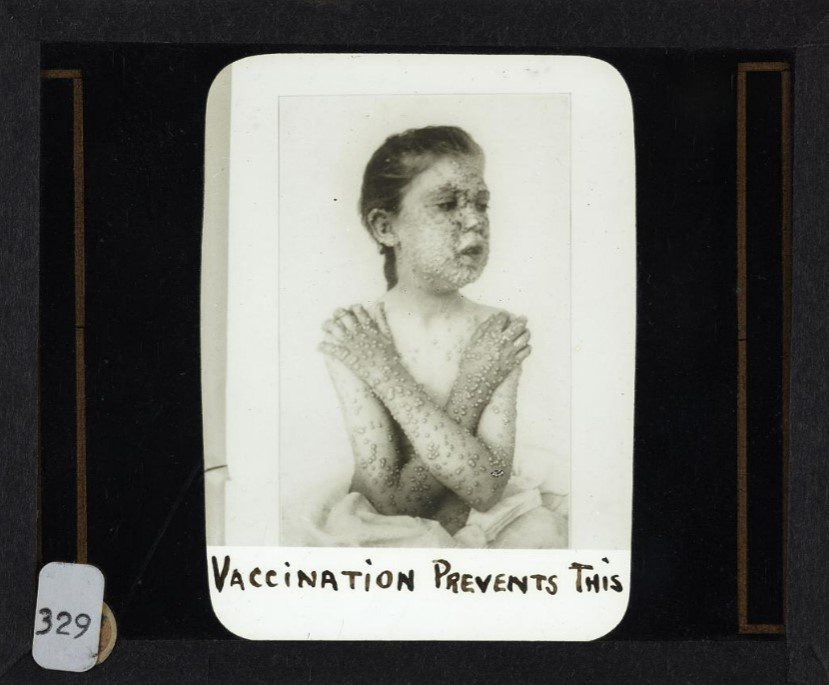

Unchecked, smallpox kills more than one in 10 of its victims, leaving many of the rest blind, disfigured and sometimes sterile. Many historians say the reason George Washington never had children was his near-fatal bout of smallpox in 1751.

The summer of 1776 was a time of crisis for the budding republic. A smallpox outbreak in the Continental Army killed hundreds. And as the soldiers came home from a failed invasion of Canada, they brought the disease to Boston.

Yet the country badly needed healthy men: The British landed on Staten Island on July 2, the same day Congress declared independence.

A perfect solution beckoned: inoculation, the 18th-century precursor to vaccination. As historian Elizabeth Fenn explains, the physician would make small incisions in the patient’s skin, then introduce scabs or pus from a person with smallpox. The inoculee would then contract a mild form of the virus, only one-tenth as lethal as the accidentally acquired version.

It would be 20 years before English scientist Edward Jenner pioneered the practice of immunizing people against smallpox with the similar cowpox virus, which is harmless to humans. Since the Latin word for cow is “vacca,” that process became known as vaccination.

In Colonial times, people who got inoculated generally did so in groups in order to keep down the cost and logistical complications. For the several weeks that they remained contagious, they would take over a home or tavern and proclaim it a smallpox hospital: off-limits to everyone but inoculees.

Boston and other towns required people undergoing inoculation to remain indoors and post red warning flags around the immunization site. Sometimes, though, restless individuals would slip out, endangering neighbors who either could not afford the expensive procedure or chose not to undergo it. Even when inoculees remained indoors, townspeople so feared catching this horrific disease that they often rioted against doctors who set up inoculation sites.

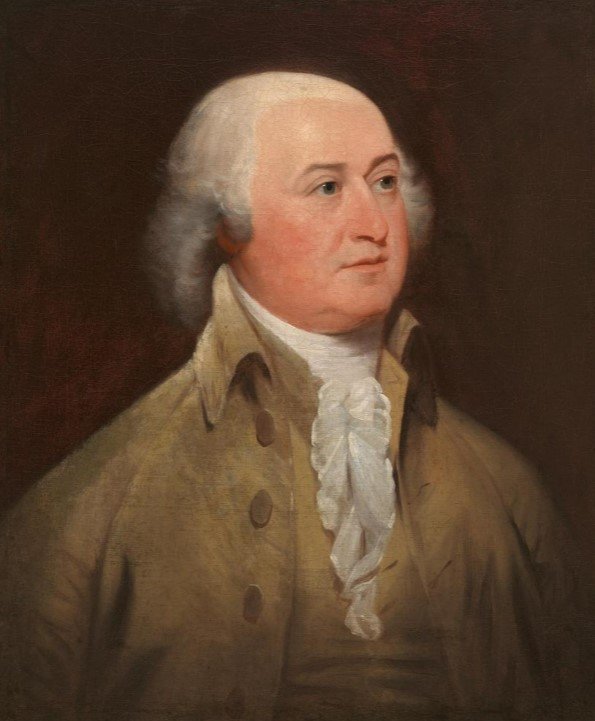

But by early summer 1776, the majority of not-yet-inoculated Bostonians were eager for the procedure – and so were many out-of-towners. Abigail Adams, famous today for imploring the Continental Congress to “Remember the Ladies,” acted quickly to inoculate herself and her children. Traveling from the nearby town of Braintree to Boston for the treatment, she wrote her husband, future president John Adams, “Our Little ones stood the operation Manfully … The Little folks are very sick then and puke every morning, but after that they are comfortable.”

Still, others refused, and Boston’s selectmen (city council) could not just let everyone decide for themselves. A patchwork of families, some undergoing and some refusing inoculation, would assuredly have set off an epidemic. So Massachusetts legislators made a bold decision. Since most Bostonians wanted to be inoculated, they would not, per usual, have to confine themselves to smallpox hospitals.

Instead, they would have the run of Boston, and the anti-inoculators would be the ones who had to either lock down or get out of town before inoculation began.

Until the city was deemed safe, guards would be posted at the sole road and several ferry landings connecting Boston to the wider world. Only those who had already had smallpox would be allowed in, and no one could leave until the selectmen deemed them smallpox-free.

By July 18, when Col. Thomas Crafts stepped out onto the balcony of the Massachusetts State House to read the just-received Declaration of Independence, no one in attendance needed to fear either catching smallpox or giving it to someone else.

Abigail Adams was among the “Multitude” who attended the reading. As Crafts finished the Declaration of Independence and shouted, “God Save our American States,” Adams reported, “the Bells rang … the cannon were discharged, the platoons followed and every face appeard joyfull.”

As late as August 26, Boston leaders were still trying to stamp out vestiges of the smallpox virus, but their bold action had prevented an epidemic. Nearly 5,000 people had been inoculated. That was equivalent to a third of Boston’s population, though about half of the inoculees were actually out-of-towners like the Adams family.

At the time, Boston had five newspapers, but no one used their pages to complain about the lockdown and other enforcement measures.

Some people took their belief in the individual’s responsibility to the community to extremes. The claim that “Every man in a republic is public property” came not from some crazed utopian but from Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. And Benjamin Franklin, in a Christmas 1783 letter advocating federal taxes to pay off the Revolutionary War debt, conceded that citizens have the right to retain enough property for their survival and for “the Propagation of the Species.” But he added: “all Property superfluous to such purposes is the Property of the Publick.”

Few Americans today would go as far as Rush and Franklin, but their comments, like Boston’s July 1776 decision to turn itself into one giant immunization site, remind us of the American Revolutionaries’ provocative conviction that communities have rights, too.

This story appeared first in The Conversation on Oct. 6, 2021. The Conversation is a community of more than 135,400 academics and researchers from 4,192 institutions.

Read Next:

Coffee or Die is Black Rifle Coffee Company’s online lifestyle magazine. Launched in June 2018, the magazine covers a variety of topics that generally focus on the people, places, or things that are interesting, entertaining, or informative to America’s coffee drinkers — often going to dangerous or austere locations to report those stories.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.