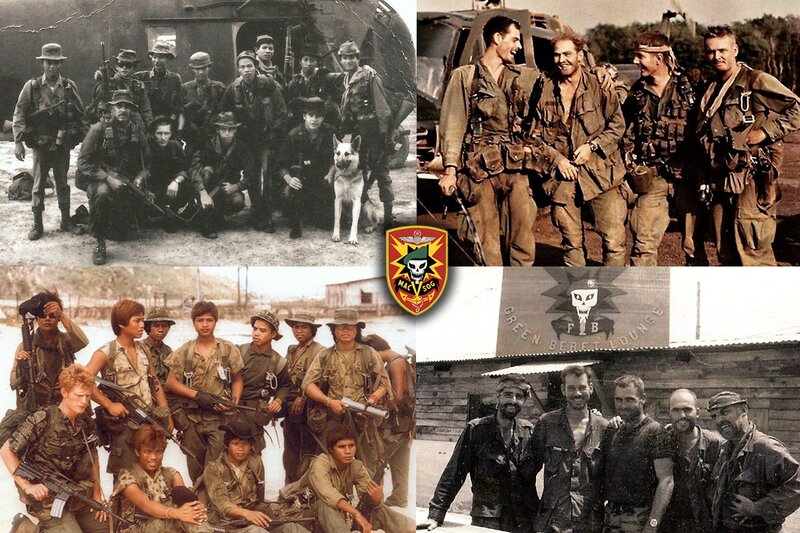

Patrick Watkins (left) and John Stryker "Tilt" Meyer (right) during their service in MACV SOG | Composite by Coffee or Die.

A Cessna Skymaster is a two-seat, two-engine reconnaissance airplane. This one fell out of the sky, its front engine sputtering and trailing smoke over the thick jungle canopy of the Laos/Vietnam border. The landing gear buckled as it hit the field's uneven ground, and the aluminum frame bent. Propeller props smacked the earth, chucking dirt high into the air.

As they landed, they slammed into an embankment hidden in the twisted green undergrowth. The two pilots on board were bucked out of their seats and thrown into the dashboard. The rear engine, located behind the cockpit, punched through the back of the aircraft and was hurled against their backs.

Miles away on FOB 1 (Forward Operating Base 1), a six-man team of three young Green Berets and three allies geared up to hoof it to the crash site. They took their short-barreled CAR 15s, sawed-off M79 grenade launchers, a dozen frag grenades, and 1,500 rounds per man. The Sikorsky HH-3E “Jolly Green Giant” helicopter landed, and the team maneuvered to the crash sight under intense enemy fire.

As they reached the crippled plane, they quickly realized that the pilots were dead and their bodies could not be removed from the wreckage. The South Vietnamese kept an untold number of enemy NVA (North Vietnamese Army) at bay as the American Special Forces men scooped up all items of value — reconnaissance maps, data papers, watches, and wedding rings off the hands of the dead men. The enemy would take anything left behind. They broke contact once the mission was complete and circled back to the LZ (Landing Zone).

The LZ was all sorts of chaos. As the helicopter circled above the ongoing firefight, one of the crew members tossed the extraction ropes out the side door. The team snapped into the “McGuire Rig,” which was, in short, a multi-person harness at the end of a 150-200 foot rope secured to the helicopter.

Bullets whipped and snapped past them; their weapons roared as they attempted to buy just enough time to literally get pulled into the sky and speed out of enemy territory. Soon, their boots left the ground as they were gently lifted into the air.

A Douglas A1 Skyraider aircraft flew directly beneath them, roaring between the dangling men and the earth below. Bombs of gelatinous napalm erupted as they dropped their payload — the jungle where they had just been fighting for their lives was transformed into fire and brimstone in the blink of an eye.

These are the men of MACV SOG.

The McGuire rig was unique in that it didn't require Soldiers to carry equipment to use it, but they could not get hoisted into the helicopter. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Officially formed in January 1964 during the Vietnam War, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV SOG) was a highly classified, multi-service Special Operations unit that required a mastery of unconventional warfare.

The unit was formed to fight in what became known as “The Secret War” The VC and the NVA weren’t playing by the rules. For example, they would cross borders and operate in countries Americans couldn’t enter. Suppose the NVA wanted to move several divisions to a different part of Vietnam. In that case, it might be easier and safer to move troops into Laos and cover as much distance as possible before re-entering Vietnam on various missions. Of course, tracking major enemy troop movements is vital to any sort of military success, so MACV SOG would have been called in to locate these units when necessary. Coffee or Die Magazine spoke to John Stryker “Tilt” Meyer, a MACV SOG veteran. “There were anywhere from 50 to 100,000 NVA in Cambodia,” he said. “They would come across the border, into South Vietnam, attack our aid camps, attack our allies, and then go back to Laos or Cambodia.”

One can imagine the danger of operating that deep behind enemy lines with the equipment on your back and only a handful of men at your side. Serving in MACV SOG wound up becoming one of the most dangerous jobs in the Vietnam War.

The Green Berets and other service members (who varied from SEALs to conventional Army units) who volunteered were required to sign a 20-year NDA (Non-Disclosure Agreement) to even listen to a pitch about MACV SOG. They couldn’t tell anyone, not even their families, what they were really doing in the service of their country.

Usually operating in small two-to-ten-man teams, these Green Berets fully integrated with the indigenous South Vietnamese volunteers. A typical MACV SOG patrol consisted of at least two American MACV SOG operators plus several South Vietnamese soldiers, and they would go wherever the NVA could be found.

Coffee or Die also spoke to Pat Watkins, MACV SOG veteran, and legend within their own very small community. “The younger [enlisted Green Berets] we had were really good if they could last. We were taking unbelievable casualties … If they could last long enough, they would be shit hot.”

The men of MACV SOG couldn't talk about their experiences for decades. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

The men in MACV SOG had a few top-secret objectives, like installing sensors on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, POW (Prisoners Of War) rescue missions, wire taps, and all other manners of reconnaissance. A lot of their training was conducted in-country, where demolition and close quarters fighting was emphasized.

MACV SOG was heavily focused on stealth, and a good mission meant they remained undiscovered. Sometimes they would drop a team as small as two men into the jungle for a recon mission without an option to call for help. “We never ran into friendly forces, there just weren't any friendlies there when you would run across the fence to Laos or Cambodia,” said Meyer.

Watkins spoke to their saving grace: air assets. “I wouldn’t be here today if it wasn’t for god dang Air Force, Marine Corps, Navy Air Support. They kept us going.”

Several teams of MACV SOG. Images from sogsite.com.

Despite their small numbers, the men of MACV SOG could pack a serious punch. “On October 5th, 1968, a nine-man team came up on 10,000 NVA,” Meyer recollected. “Between the recon team and TAC Air (Tactical Air Command), they inflicted 90% casualties on a 10,000-man NVA unit.” Years later, one of the South Vietnamese men of Meyer’s MACV SOG team spoke to the General of the Division they had come head-to-head with. According to Meyer, the General said, “I was lying there on the ground watching you kill my men, and I couldn't do anything about it.”

For a regular unit, with artillery, air support, and nearby friend units, an encounter against an enemy of that size would often result in panic and possibly retreat. For these men, the thing had to run its course. All they had were their teammates and TAC Air.

On his first tour to Vietnam, Meyer and his buddies clamored off a helicopter and set foot on FOB 1 for the very first time. As they ran, crouching to clear the blades of the aircraft, a sister MACV SOG team boarded — two Americans and four volunteer South Vietnamese troops. They were heading out on a recon mission and would never be heard from again. “Glen Lane and Robert Owen are two of the fifty Green Berets that are listed as Missing In Action today,” Meyer said. That was his introduction to the "Secret War."

John Stryker "Tilt" Meyer gearing up for a mission. Images courtesy of Meyer.

A six-man MACV SOG team, “Spike Team Idaho,” flew deep into enemy territory. Meyer was with them, relatively new to the war, and he had no idea this would be his first major battle. At his side sat Don Wolken, the team leader, and Jim Davidson, who had just come in from the 173rd Airborne. Three experienced indigenous personnel also accompanied them: Phuc, Hiep, and Sau.

Their objective was to reach an American POW base, known to them as “Target Echo 4,” where they intended to free as many POWs as possible and then return to South Vietnam.

The six men hit the ground and started to walk, armed to the teeth with their usual loadout. Meyer and the others cut through the jungle in secret, but it wasn’t long before they started hearing distant cracks between the trees — gunfire.

“We couldn’t tell if they had found our trail or not,” Meyer said, but he knew they were being tracked. The trackers were signaling to each other with sporadic gunfire, likely also hoping that the MACV SOG element would fire back and expose their position.

Without engaging, they pressed on through the evening until night fell. Then, another round was fired, and this one was about 30 meters away. They deployed claymores, stayed tight, and pulled security as they assessed the situation. Still, they managed to stay hidden.

The next day, they kept on toward the POWs, moving along an animal trail. Meyer glanced back, and he could see two NVA soldiers among the underbrush, holding their AK-47s with smiles plastered across their faces. “We knew we were going to make contact,” Meyer said.

Immediately, the team sought out high ground. They set up on a knoll, put everyone on line, and tried to reach headquarters. That’s when the real firefight broke out.

For four hours, they engaged enemy forces trying to rush the knoll. After a while, Hiep crept over to Meyer and told him to look down another part of the hill. “They were stacking up the dead bodies,” Meyer said. “They were trying to get the bodies stacked up so they could get on top and shoot down at us. And that was, like… that was a real gut check. These guys were serious. They kept coming. Wave after wave, they kept hitting us.”

They made contact with friendly forces via radio, and soon American air power started to tear the NVA forces apart. “The first time I’d ever smelled human flesh burn, it was due to those napalm runs.”

At last light, a South Vietnamese pilot braved the enemy onslaught and hovered in harm’s way until Meyer and the rest of Spike Team Idaho were safe. “At that point, I was down to my last magazine and my last hand grenade.” Later, they would discover 48 holes in the helicopter that extracted Spike Team Idaho.

“None of our people were hit. Just amazing,” Meyer added. “Welcome to the Secret War.”

If you want to hear from Pat Watkins and Tilt yourself, we interviewed them here:

Luke is the author of two war poetry books, The Gun and the Scythe and A Moment of Violence, and a post-apocalyptic novel, The First Marauder. He grew up in Pakistan and Thailand as the son of aid workers. Later, he served as an Army Ranger and deployed to Afghanistan on four combat deployments. Now he owns and operates Four Hawk Media, a social media-focused marketing company.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.