The Daring Vietnam War Hostage Rescue Mission That Only MACV-SOG Could Pull Off

Five hours before launch, Colonel Arthur D. “Bull” Simons stood in front of his handpicked assault force of U.S. Army Special Forces soldiers and said, “You are to let nothing — nothing — interfere with the operation. Our mission is to rescue prisoners, not take prisoners.” The 56-man element, who had spent the past three months rehearsing on a mock CIA compound with an identical layout of the Son Tay Prison Camp, listened intently, knowing the mission had to be perfect if they were going to make it back alive.

“And if we walk into a trap, if it turns out that they know we’re coming, don’t dream about walking out of North Vietnam — unless you’ve got wings on your feet. We’ll be 100 miles from Laos; it’s the wrong part of the world for a big retrograde movement. If there’s been a leak, we’ll know it as soon as the second or third chopper sets down; that’s when they’ll cream us. If it happens, I want to keep this force together. We will back up to the Song Con River and, by Christ, let them come across that God damn open ground. We’ll make them pay for every foot across the sonofabitch.”

I Volunteer: Send Me

Pentagon bigwigs and strategic planners back in Washington monitored developments in the heavily defended Son Tay prison camp, which was located approximately 23 miles west from the famed “Hanoi Hilton.” Negotiations with the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) were at a standstill; reports and rumors spread like wildfire across the U.S., detailing the hellacious conditions that more than 450 American prisoners of war (POWs) faced while inside these torture camps.

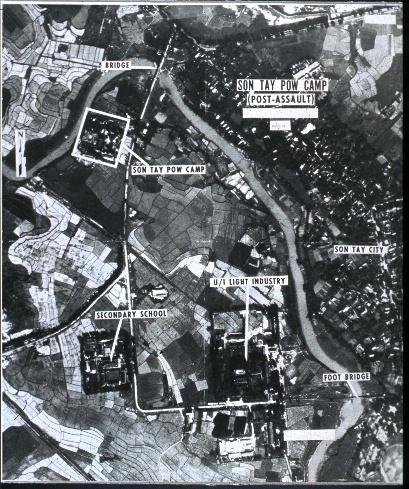

The Son Tay complex was surrounded by MIG interceptor air bases, anti-aircraft sites, and surface-to-air missile installations. The Son Tay prison camp had 40-foot trees, fields of rice paddies, and was near the Son Cong River. SR-71 “Blackbirds” reconnaissance aircraft orbiting 80,000 feet overhead snapped detailed photographs of the landscape below. Analysts determined stress signals drawn by POWs. At Son Tay, a letter “K” was drawn in the dirt and was said to mean “come and get us.” The letters SAR (Search And Rescue) also appeared in other images displayed with prisoner’s laundry.

Intelligence officers and analysts from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) identified every pathway, building, and unknown from the aerial photos. The National Security Agency (NSA) helped provide a more defined picture with its usage of low-altitude, unmanned reconnaissance drones called Buffalo Hunters. They were flown at treetop level to get pinpoint access into the compound. They determined that a force of 12,000 NVA soldiers were just miles from Son Tay, and it was believed that 57 POWs were being held captive in one of the four main buildings in the complex. About 400 meters south, there was a separate compound that was referred to as the “secondary school.”

In July 1970, the CIA, the NSA, and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) introduced a plan dubbed “Polar Circle” to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Brigadier General Donald D. Blackburn, who led a motley crew of “fence sitters,” intelligence assets, and a guerilla element during World War II, recommended the team be assembled of Army Special Forces soldiers. Blackburn had wartime experience in World War II, but more importantly, since 1965, he had instrumental involvement in MACV-SOG (Military Assistance Command Vietnam-Studies and Observations Group) programs like Project Leaping Lena, Operation Shining Brass, and Operation White Star. The successes and failures taught Blackburn valuable lessons in counterinsurgency, deep penetration reconnaissance, and cross-border tactics fighting in Laos, Cambodia, and North Vietnam.

From the initial planning phase of Polar Circle came two following phases: Operation Ivory Coast (Training) and Operation Kingpin (Rescue). Blackburn selected Colonel Arthur D. Simons to lead the team; he selected and trained 100 Special Forces soldiers from the 500 initial volunteers. Simons was previously awarded the Silver Star for the rescue of 500 POWs during the notorious Cabanatuan Raid in the Philippines. His experience as a ground force commander was invaluable, and coupled with volunteers from the U.S. Air Force Special Operations Command, 98 airman aboard 28 total aircraft ensured the very best were working together.

The members of the assault force still didn’t know who or what the target was. “We thought we were going to rescue people being held hostage aboard a hijacked plane,” said Terry Buckler, a 20-year-old sergeant who was on the historic mission. “They kept us pretty much in the dark.”

Starting in mid-September, the assaulters endured three months of training in Florida at a CIA facility that replicated every square inch of Son Tay prison camp. “We started training in the daytime, going through dry runs,” Buckler said. “We practiced our positioning and what to do when our choppers hit the ground. There were three ships (one Sikorsky HH-3 Jolly Green Giant and two HH-53 Super Jollies) going in; Greenleaf, Blueboy, and Redwine were their radio call signs. Then we began doing night training. There was a flare ship above us that lit up the compound. We used live ammunition the entire time as well.”

“We thought we were going to rescue people being held hostage aboard a hijacked plane. They kept us pretty much in the dark.”

The assault force prepared for every scenario — during the day and at night, the identification of village surveillance and sentries, demolition charge placement, emergency trauma, and radio coordination with the birds hovering above. They even drove down to the local department store to grab bolt cutters in case the POWs were chained in place. They practiced 170 total repetitions for three months straight. This did not include the Air Force’s own rehearsals of more than 1,000 flight hours honing nighttime aerial refuelings, formation and flight patterns, and flair-dropping. Their callsigns were Apple 1, Apple 2, etc., and Banana 1.

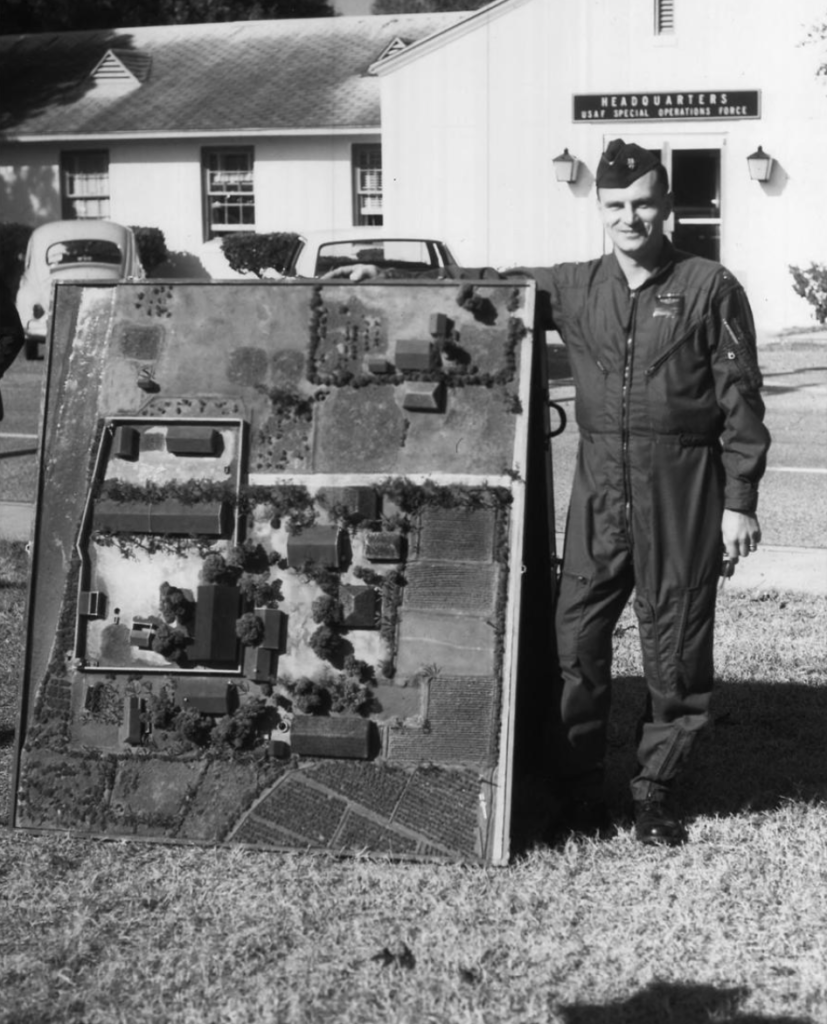

When the teams were not actively working out the kinks to find the best tools and weaponry for the task, they studied a miniature 3D tabletop replica of the Son Tay prison compound. The replica was designed by Kenny Lane, the CIA’s reconstructive models wizard, who over his career had built Manuel Noriega’s vacation home in Panama and the Kremlin in Moscow. It was codenamed “Barbara” after Barbara L. Strosnider, a secretary from the United States Air Force Directorate of Plans.

“Studying ‘Barbara’ required a special optical viewing device that could be placed anywhere inside the tabletop model,” Major John Gargus, one of the Air Force’s special mission aviators attached to this mission, wrote. “When one looked through its precisely scaled eyepiece the scene would be magnified to life size, and the viewer would find himself standing at any selected spot inside the prison compound.”

As training and operational plans were ironed out, the assault force was flown to a staging area in Tahkli, Thailand, in November 1970. They were briefed on their mission to rescue American POWs in what was expected to be the dragon’s den. The first of three ground elements, callsign Blueboy, led by Dick Meadows, planned to fly to the “X” and land inside the compound. Meadows was a living legend, having reached the rank of master sergeant by his 20th birthday. Callsign Redwine, the second element, prepared to secure a canal junction to the south of the camp to control their extraction. Greenleaf provided security for the other elements and would make adjustments as the raid progressed.

30 Minutes or Less

For such a raid, perfect weather conditions were paramount but not the deciding factor since the status of the hostages dictated their every move. Days before, a reliable intelligence source in Hanoi stated that the POWs had been moved. Intelligence analysts and officers scrambled to get a picture of ongoings inside the camp. The third phase, Operation Kingpin, was finalized by President Richard Nixon, who ordered the “go” on Nov. 20, 1970. The mission launched with 56 raiders, while the other 44 soldiers were left on standby. The assault force boarded their helicopters at 11:10PM for North Vietnam.

“We’re Americans. Keep your heads down. This is a rescue … we’ll be in your cells in a minute.”

Another action had been approved all across Vietnam — a diversion from air and support operations, which included 116 total aircraft from seven air bases in Thailand and three nearby aircraft carriers. U.S. Navy aircraft were not dropping bombs but flares to keep attention away from the MACV-SOG task force. In addition, 10 F-4Ds searched for Vietnamese MIGs flying in the area to retain aerial superiority.

The hum of the helicopters allowed the raiders to focus as they crossed the Laotian border. The radios were silent; the men lacked body armor and had limited night vision capabilities — but American lives were at stake, and they were going in to send the message that the U.S. military’s reach extends into the center of any enemy stronghold.

MC-130 Combat Talon aircraft escorted the helicopters flying low to avoid radar detection to the target. The first to reach the compound were members of Blueboy, who had crash landed after the rotor blades hit limbs of trees, causing them to explode leaves, debris, and branches everywhere. The impact had such violence that the door gunner was thrown from the chopper, but he sustained only minor injuries. Meadows grabbed a megaphone, put it to his mouth, and said, “We’re Americans. Keep your heads down. This is a rescue … we’ll be in your cells in a minute.”

Buckler’s Redwine element landed outside the compound, blew a hole in the 7-foot-tall wall, and set up firing positions. Some areas had not been illuminated by the hovering flagship above. Simons’ Greenleaf element had touched down in the wrong location and discovered that the secondary school was, in fact, an NVA barracks. A firefight ensued, and during the confusion, Redwine and Greenleaf exchanged gunfire.

With 17 minutes on target, Simons, the ground force commander, had declared it a dry hole and that the POWs had been moved. Initial after-action intelligence reports stated that the NVA had expectations of a monsoon that would cause the nearby river to flood the compound. Gargus, however, later found NVA command documents suggesting the compound was vulnerable to a rescue.

After it was determined that no POWs were present, the assault force boarded their helicopters to escape. Buckler later said he wasn’t scared during the operation. However, it was during their exfiltration that he and Captain Dan Turner watched a door gunner use his minigun to suppress fire from Hanoi below.

“About that time what looked like orange telephone poles started coming up at us,” Buckler said, referring to surface-to-air missiles. “Our pilot was doing everything he could to dodge them. That’s when it got really tense. They turned it into a media event, trying to get as much publicity out of the raid as they could. In retrospect, it was a good thing to do. It proved that we could get into the enemy’s backyard undetected and get out without losing anyone.”

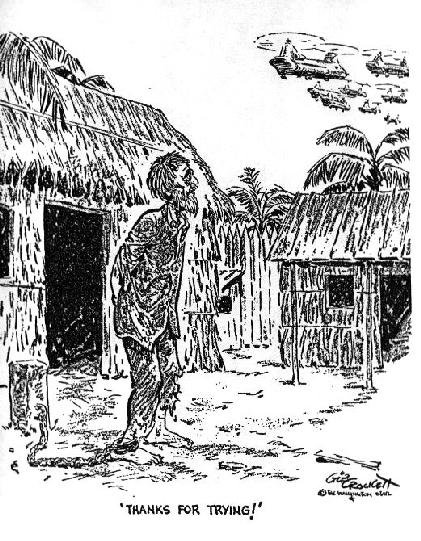

The press learned of the operation and broke the news to the world. Political cartoonist R.B. Crockett drew a comic of a bound American POW watching American helicopters infil overhead, along with the quote, “Thanks for trying.” The mission that lasted just 27 minutes was deemed an intelligence blunder but a tactical success. Those who participated in the mission were later awarded six Army Distinguished Service Crosses, five Air Force Crosses, four Distinguished Flying Crosses, and at least 85 Silver Stars. The tabletop model of “Barbara” is now on display in the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Before there was the Army’s Delta Force, Naval Special Warfare Development Group, or the 24th Special Tactics Squadron, there was MACV-SOG, comprised of all volunteers, tasked with the most dangerous missions and responsible for carrying out both rescues and strikes within the target package.

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.