Rise of the Deadeyes: How Marines Evolved From Infantrymen to Scout Snipers

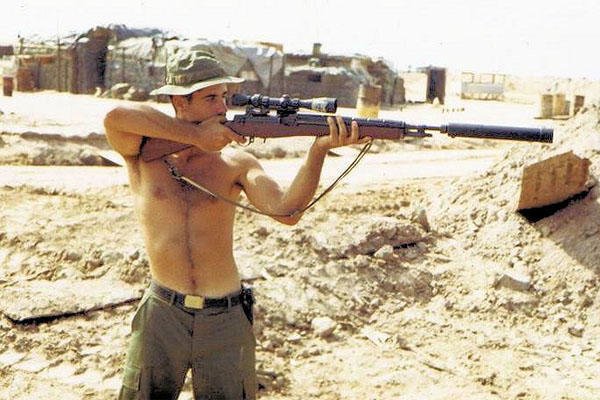

Sgt. Tim R. Lee, Scout Sniper, Scout Sniper Platoon, Headquarters and Support Company, Battalion Landing Team 1st Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit, fine-tunes the sights of his M40 sniper rifle before beginning the first stage of a three-day platoon competition in Djibouti March 25, 2010. Photo courtesy of Sgt. Alex C. Sauceda.

A section of rope was replaced with piano wire, then rolled in glue and crushed glass. It was an up-close-and-personal weapon of choice for “Wild Bill” Emerick, a former club brawler from Chicago who rescued wounded Marines from a kill zone in Guadalcanal and later escaped unscathed from Tarawa. Most Marines valued hand-held weapons in the island-hopping campaigns in the Pacific because they could kill the enemy quietly, sometimes without a sound. These weapons were particularly useful for conducting deep-penetration operations, the early trademark missions of the newly formed Scout Sniper Platoon of 6th Marine Regiment in Saipan.

In this new crack-shot unit, Emerick was one of 40 Marines hand-picked from hundreds of volunteers. The Scout Sniper Platoon required all its Marines to have prior combat experience, expert marksmanship, and a wild streak.

Before they ever set foot on Saipan, their antics began near Parker Ranch in Hawaii in 1944. When they weren’t being taught the proper concealment methods and camouflage or giving each other black eyes and bruises in jiujitsu and fistfights, the Marines proved themselves masters of thievery. First, they took an Army colonel’s chicken coop — and all the chickens; then an Army jeep they painted over in Marine colors and used for booze runs; finally, they set up a baseball diamond and stashed their stolen alcohol underneath the bases, which were made from oil-drum lids.

The Marines had acquired a reputation, and envious outsiders began calling them the “40 Thieves,” a nickname that inspired the title of the book 40 Thieves on Saipan: The Elite Marine Scout-Snipers in One of WWII’s Bloodiest Battles. After arriving on the island in June, the Marines spent two weeks behind enemy lines. They had no extra clothes to change into and suffered through bouts of malaria and dysentery while under constant enemy gunfire.

In the early days, even in an elite unit such as the “40 Thieves of Saipan,” Marines were little more than glorified infantrymen. They were given the best training available and excelled at killing enemy combatants with their hands, hand grenades, and rifles. The science of a well-placed shot and the technology to help achieve it didn’t come until later.

In Korea, Scout Sniper teams were armed with old M1903 Springfield rifles from World War II, while others favored the newer M1-C semi-automatic rifles. These Marines kitted their rifles with cheek pads, flash hiders, leather slings, and 2.2X telescopic sights. They worked in pairs — smaller groupings than the platoon-sized elements in the previous war. One Marine was responsible for spotting targets with either binoculars or a scope while the other operated the gun.

In Seoul, beyond the hills and ridges populating the Korean peninsula, the enemy was holed up inside buildings. While this was a marked change from the jungle warfare of the Pacific theater, some of the Marines’ tactics remained the same. These small working teams moved house to house and would engage North Korean combatants at any range.

It wasn’t until Vietnam that the legend of the Marine Corps Scout Sniper truly emerged. And in this lore were two Marines whose superior marksmanship and patience had earned them fear and respect. The most famous was Gunnery Sgt. Carlos Hathcock, known to the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong as “The White Feather” (Du kích Lông Trắng) in reference to the feather he tucked in his hatband.

Hathcock volunteered for a solo mission to infiltrate NVA territory and assassinate an NVA general. He was dropped off by a helicopter and crawled 1,500 yards on his stomach for four days and three nights without sleep. He was even nearly bitten by a snake while waiting patiently — and perfectly still — to take a shot as roving enemy patrols passed him. Hathcock made 93 confirmed kills.

Sgt. Chuck Mawhinney, who holds the record for most confirmed sniper kills — 103 — was not as notorious, but his exploits were equally astonishing. He preferred the M40, a modified Remington 40X bolt-action chambered in 7.62×51 mm NATO. Before missions, he would place an empty cigarette pack at 50 yards, using it to adjust his rifle’s scope. Mawhinney engaged most enemy combatants at distances anywhere between 300 and 800 yards and had confirmed kills at more than 1,000 yards.

“When you fire, your senses start going into overtime: eyes, ears, smell, everything,” Mawhinney told The Baltimore Sun in 2000. “Your vision widens out so you see everything, and you can smell things like you can’t at other times. My rules of engagement were simple: If they had a weapon, they were going down. Except for an NVA paymaster I hit at 900 yards, everyone I killed had a weapon.”

On Valentine’s Day, 1969, Mawhinney watched as an NVA scout waded into a river before his NVA regiment crossed it. “Pretty soon a bunch more showed up, and when they got out into the water I started shooting, killing 16, all with head shots, until they stopped coming,” he said. “I shot the rifle 16 times. Evidently that intimidated the rest of the unit, and they all pulled out during the night. The river’s current carried away all but two of the NVA I’d shot.”

The tactics, techniques, and procedures from the Vietnam War evolved beyond jungle fighting to urban street battles in Iraq and the mountains of Afghanistan. While the legends of the Marine Corps’ Scout Snipers are exclusively spoken about inside team rooms, sometimes word of their heroism creeps into the public view. Sgt. Joshua L. Moore, a scout serving with a Scout Sniper Platoon in 2nd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment, Regimental Combat Team 1, was awarded the Navy Cross for heroism while in a hide site northeast of Marjah, Afghanistan.

“Two grenades were thrown over the north wall, and both of them hit me in the back and rolled away,” Moore said. “Fortunately they landed next to each other, and I picked the first one up and threw it out.” The second grenade didn’t detonate. Moore had to crawl out of the building under intense enemy fire to regroup with his platoon and evacuate the wounded. Marines have been fighting the Global War on Terror for nearly 20 years now, and Moore and his actions exemplify the best the US Marine Corps has to offer.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2021 edition of Coffee or Die’s print magazine.

Read Next: Inside the Marine Corps’ New Recon Sniper Course — A Visual Journey

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.