We Must Revisit Tarawa Amid the Marine Corps’ Renewed Focus on Amphibious Warfare

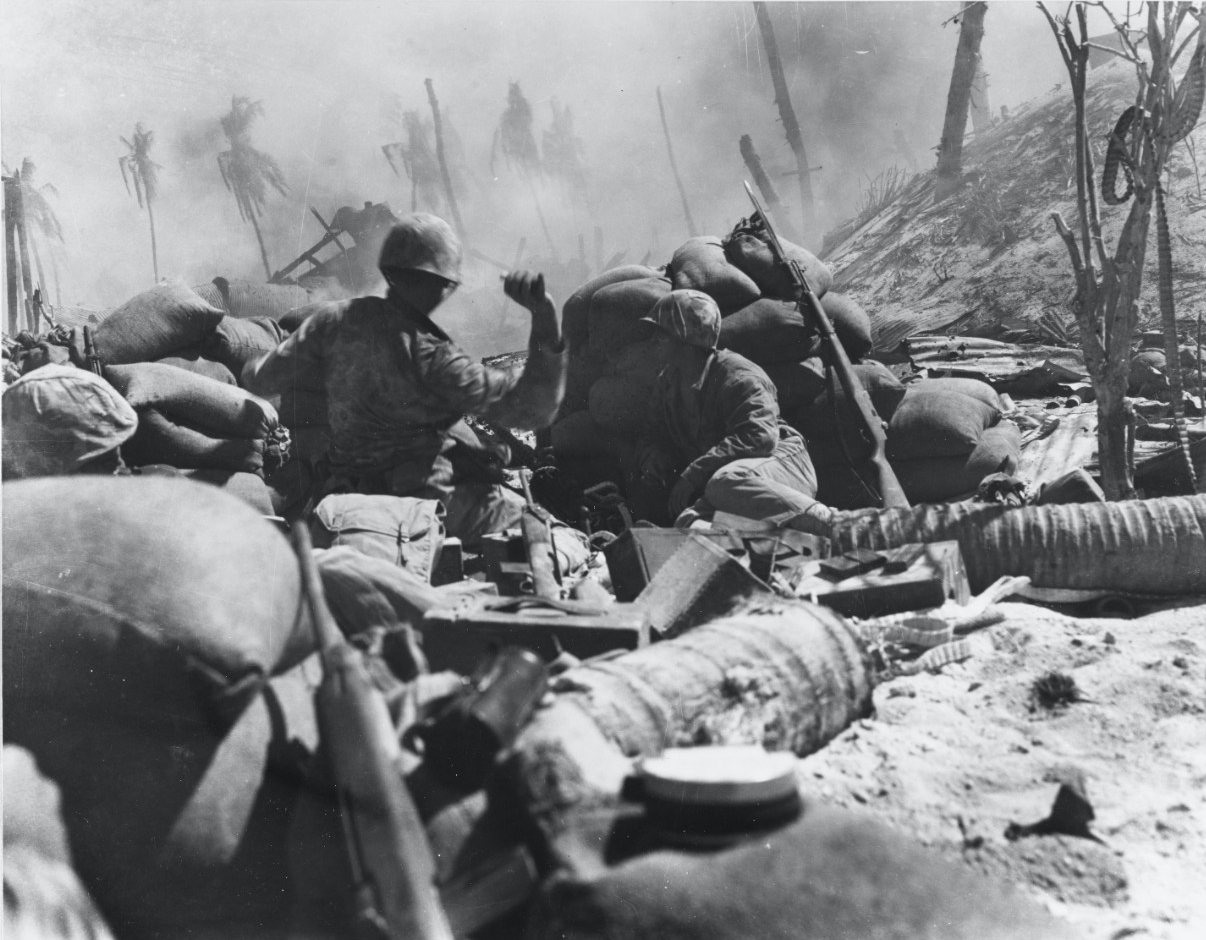

A Marine throws a grenade during the Battle of Tarawa, Nov. 22, 1943. Note M1 rifle with fixed bayonet. Photo courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command.

Clad in dress blues, the six Marines sidestepped in perfect unison, working together to support the weight of the flag-draped casket held between them. The brass of their buttons gleamed in the early morning light of Nov. 20, 2019. Rows of white marble headstones stretched from Section 60 to every horizon of Arlington National Cemetery’s gently rolling hills.

The Marines had practiced every aspect of their funeral detail tirelessly in order to give Pvt. Edwin Benson the proper burial he had so long been denied. Benson had served as a rifleman during World War II and was one of thousands of Marines and sailors of the 2nd Marine Division killed in action during the battle of Tarawa. His remains had been lost to history, lying in an unmarked grave containing the unidentified dead from the three-day fight. They were left in that far corner of the Pacific for 76 years before finally being identified and interred in Arlington.

Recently, the US Marine Corps announced its shift in focus away from experimental urban tactics toward conventional littoral warfare. With the Corps’ new priorities and the anniversary of the battle approaching, Marines must revisit how the “sunny tropic scenes” where the sacrifices of Benson, and so many other Americans, taught us valuable lessons in amphibious combat.

From the fighting tops of colonial frigates to the 15th and 26th Marine Expeditionary Units’ launch into Afghanistan, the Marine Corps has remained a naval landing force. While their traditional role as “sea soldiers” has existed in a constant state of flux, nowhere has the amphibious nature of Marines been more clear than in the island-hopping campaigns of World War II. Movies and TV have invaded every living room in America with depictions of gung-ho Marines wading ashore tropical beaches, but the battle for Tarawa was all but picturesque.

One of the shortest yet bloodiest battles in Marine Corps history, Tarawa cost an estimated 6,400 lives in less than three days. The Battle of Tarawa was fought almost entirely on the small island of Betio, just a speck on a larger coral atoll, itself just a piece of the larger Gilbert Islands. Betio was protected by a coral reef that extended 500 yards beyond the beach, creating a natural, shallow lagoon. The island contained a small airfield, vital to Japanese dominance in the Pacific and a key steppingstone in America’s march to Japan.

Tarawa was defended by nearly 2,600 Rikusentai, highly trained amphibious troops of the Imperial Japanese Navy, not dissimilar to the attacking Marines. Considered better trained and better equipped than their Japanese Army counterparts, the Rikusentai had been sent to reinforce the island following the famed landing on Makin by Marine Raiders. Recognizing the importance of Betio, Japan had spent the year bolstering the island’s defenses. At the time of the battle, it boasted 14 coastal defense guns, more than 500 pillboxes, 40 artillery pieces, and four 8-inch Vickers guns (purchased from the British), as well as a log seawall designed to trap any landing forces in the surf, where the defenders had registered their mortars and machine guns. Japanese Commander Shibazaki had claimed in a letter that “a million men could not take Tarawa in one hundred years.”

Following the failed British landings at Gallipoli, most countries considered amphibious assaults against defended beaches to be impossible, but the US Marine Corps strove to prove this notion wrong. The Navy prepared for the landing with an accurate, pre-invasion bombardment, successfully knocking out most of the coastal defense guns. This was succeeded by a three-hour barrage from battleships, destroyers, and aircraft. Following the bombardment, minesweepers cleared the lagoon of underwater mines, allowing for the landing craft to approach the shore.

Despite pre-landing success, the majority of Tarawa’s lessons in amphibious warfare were learned the hard way. Although the coral reef and dramatic tides were well known, they were not properly accounted for during planning. Only a small portion of the landing force was equipped in tracked landing vehicles; the rest used flat-bottomed Higgins boats. The extreme low tide left the Higgins boats stranded 500 yards from the beach, forcing the Marines to abandon ship and wade to their targets under enemy fire. Nearly every tracked vehicle was knocked out before being able to bring subsequent waves of Marines. This oversight cost the landing force dearly.

In addition to recognizing the impact of tides and the need for effective landing vehicles, the Marines again witnessed the necessity of decentralized command, and the importance of confident small-unit leaders. On the night of the first day, there was no distinction between American-held terrain and the enemy lines. Pockets of Marines created their own defenses and fought independent of the larger landing force. With serious breakdowns in communication during the day’s fighting, individuals took it upon themselves to lead ad hoc units against the Japanese — individuals like Alexander Bonnyman and Dean Hawkins.

Bonnyman was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor after he died leading a ragtag group of pioneers (what would later become 0351s, infantry assault Marines) equipped with flamethrowers and demolition charges in the destruction of the largest bombproof bunker on the island. Hawkins was also posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, after leading his Scout/Sniper platoon in clearing the beach of defenders. While leading his snipers, Hawkins was shot in the chest. Despite the wound, he assaulted three machine gun positions alone, firing point-blank into the gun ports and killing the defenders with hand grenades. He only ceased to lead the way after he was killed by a fourth machine gun. His Scout/Sniper platoon went on to play a critical role in the remaining 48 hours of the battle without him.

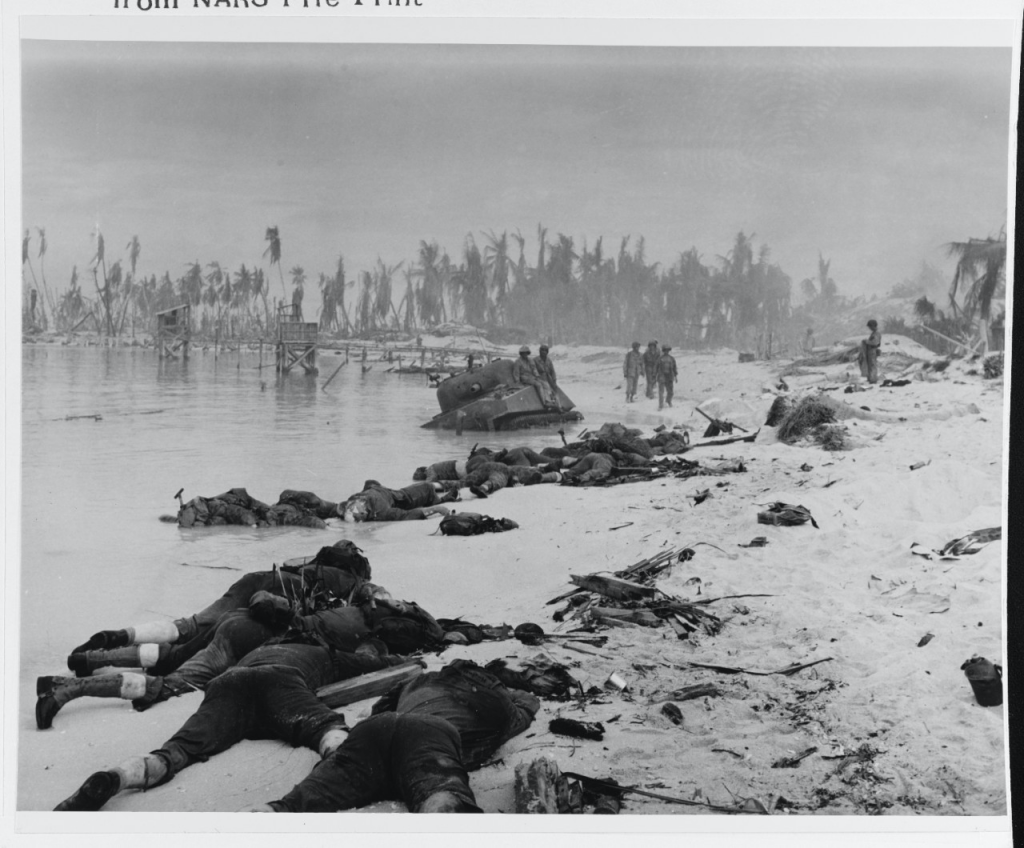

The proximity of the American and Japanese forces, all condensed into less than 1 square mile of ground, resulted in devastatingly concentrated combat. Almost 38,000 troops found themselves scrapping it out at bayonet range in a cage fight between naval superpowers. Of the landing’s first wave, 70% became casualties on the first day. Of the island’s nearly 5,000 defenders, only 17 were captured alive. Few battles have resulted in such heavy losses, while simultaneously leaving such clear lessons for posterity.

Despite being an uncommonly violent battle, Tarawa served as the proving ground for new tactics in amphibious warfare. Tracked landing vehicles and the deployment of amphibious tanks had proved vital to success in the surf zone. Accurate naval gunfire convinced the world that defending a beach was all but impossible, and an inland defense was more tenable.

Tarawa also exposed blaring holes in the existing American doctrine. Actions like those of Bonnyman and Hawkins highlighted the importance of fostering initiative and aggression among every rank, so troops would not freeze with the inevitable loss of leadership on the battlefield. Poor communication between landing forces and supporting naval fires caused the Navy and Marine Corps to permanently change how they communicated from ship to shore.

The island’s immense obstacles, both natural and man-made, also played a key role in the eventual founding of Navy UDT teams, which later evolved into SEALs. Thankfully these lessons were learned in a mere 76 hours of fighting, and subsequent amphibious landings adjusted accordingly. Less than a year later, the Marine Corps landed on the island of Saipan and conducted what is largely considered one of the most well-executed amphibious landings in military history.

Hundreds of Marine dead remain unidentified across the islands of the Pacific, a testament to the savagery of amphibious warfare. While Benson is the most recent veteran of Tarawa to be interred at Arlington, he will be followed in the coming weeks by 1st Lt. Justin Mills, Sgt. Duane Cole, Cpl. Thomas Cooper, and Pvt. William Rambo. The list goes on.

It is important that with a renewed focus on littoral warfare, the Marine Corps does not keep its sights oriented to the rear, but rather identifies potential obstacles before we face them in the wars to come. It would be unacceptable to once again find ourselves, three-quarters of a century removed, still collecting and identifying the remains of lessons learned at sea.

Mac Caltrider is a senior staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. He served in the US Marine Corps and is a former police officer. Caltrider earned his bachelor’s degree in history and now reads anything he can get his hands on. He is also the creator of Pipes & Pages, a site intended to increase readership among enlisted troops. Caltrider spends most of his time reading, writing, and waging a one-man war against premature hair loss.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.