Maverick of the Sea: How an Undersea Ace Transformed Submarine Warfare

Lt. Cmdr. Dudley “Mush” Morton received four Navy Cross medals, one Army Distinguished Service Cross, a Purple Heart, and a Presidential Unit Citation in World War II. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

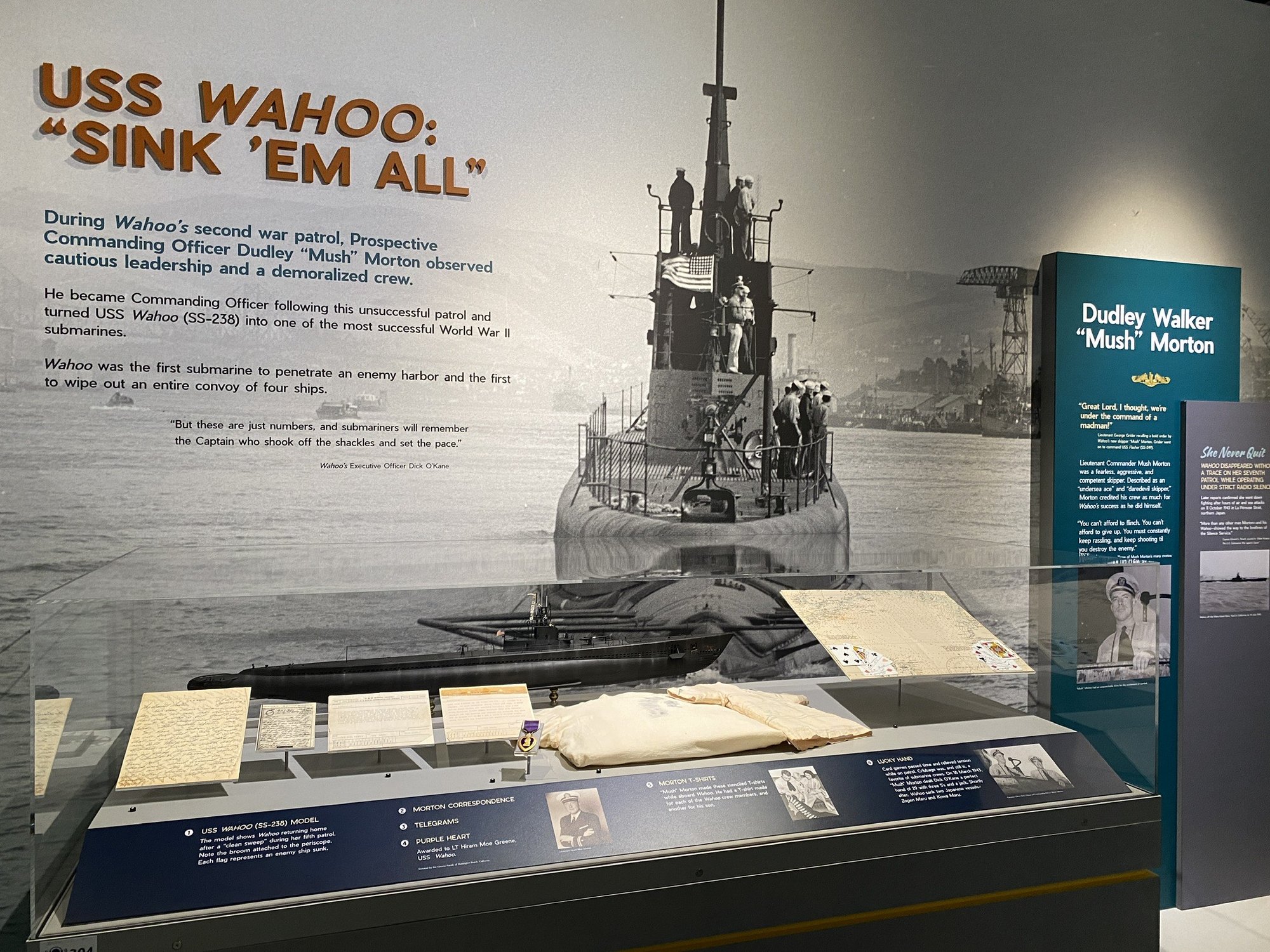

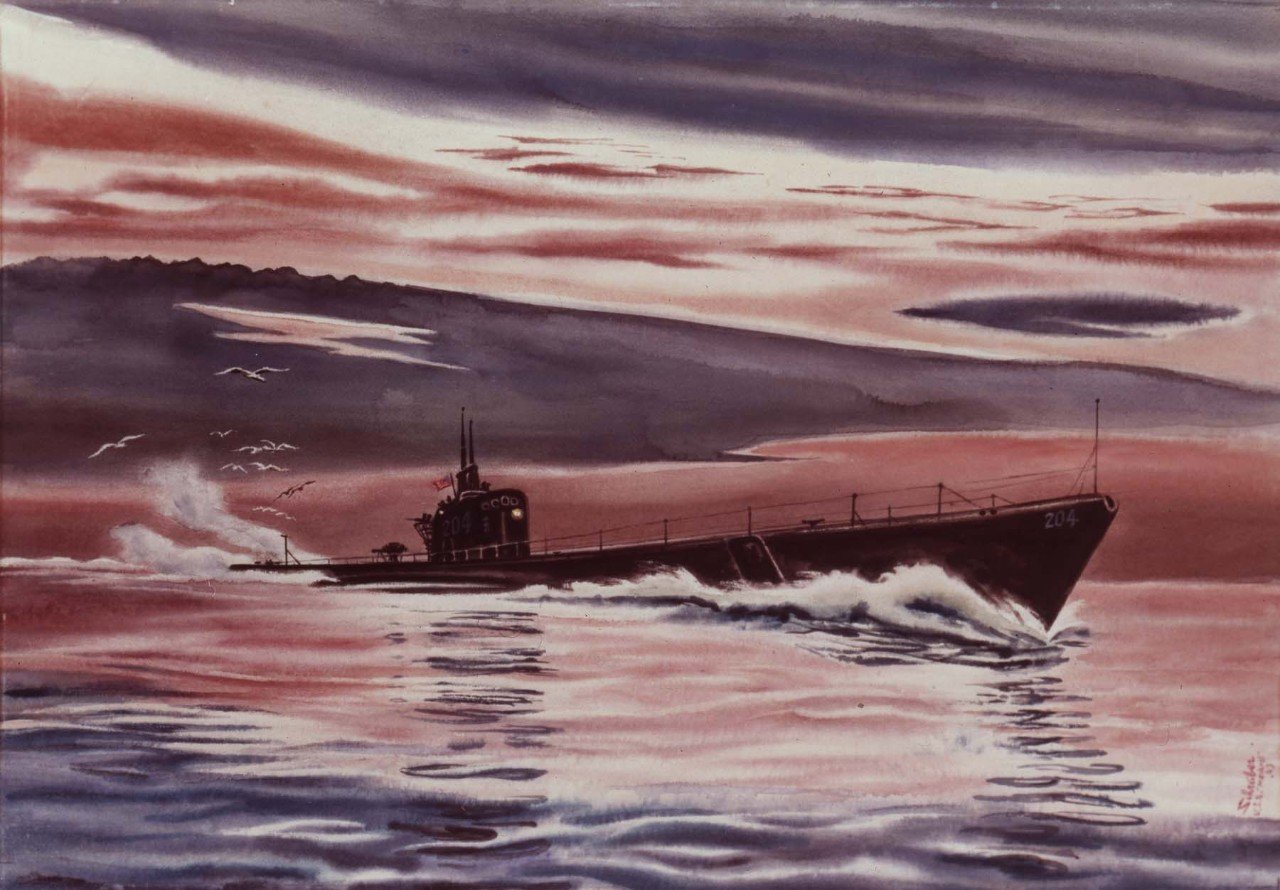

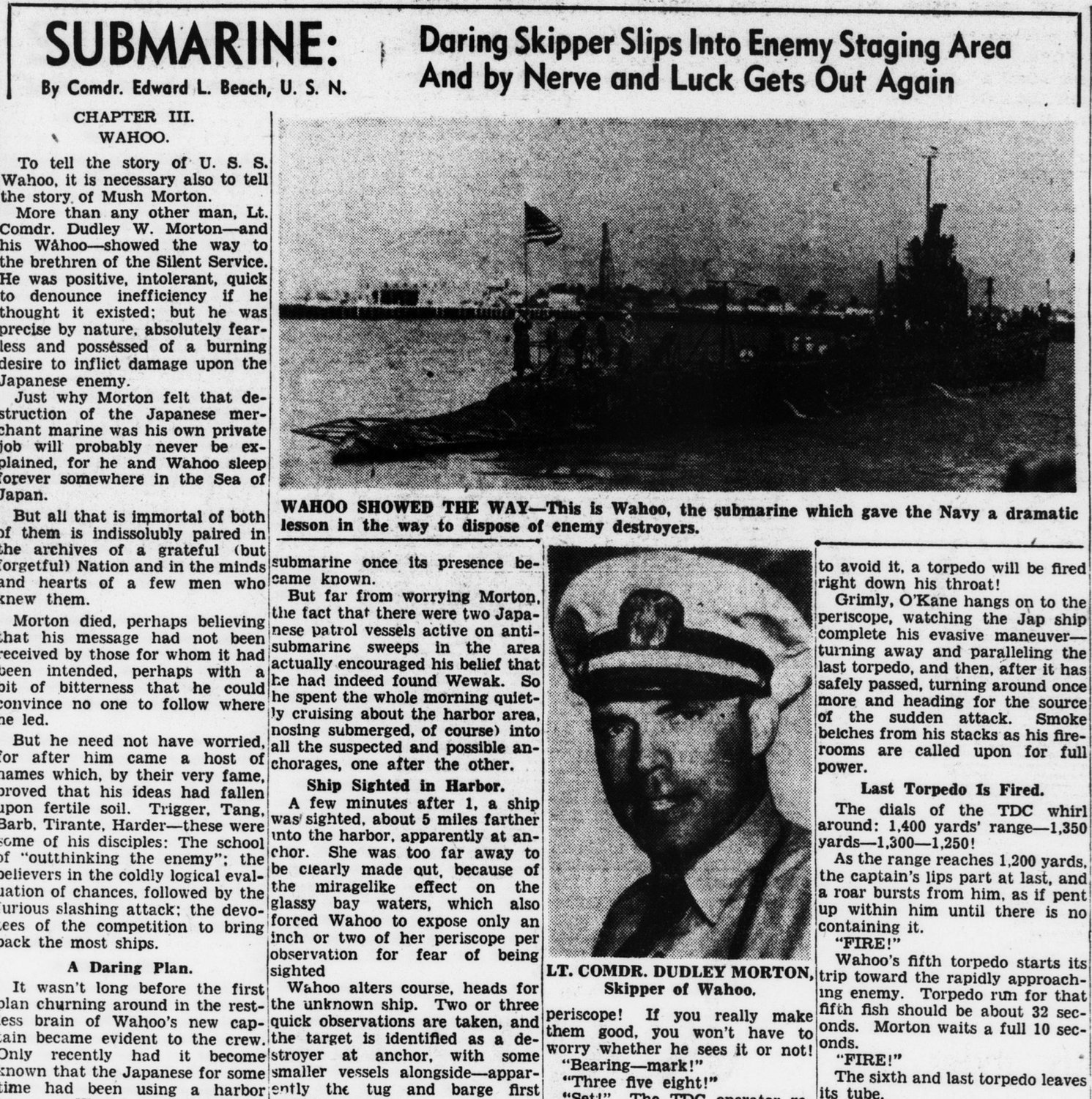

On Nov. 30, 1943, The New York Times reported one of America’s finest World War II submarine skippers, Lt. Cmdr. Dudley “Mush” Morton, was missing in action. The controversial “daredevil skipper” had engaged and sunk 19 enemy ships in just 10 months. Then, on his fifth and final war patrol as skipper, under an order of strict radio silence, the commander of the USS Wahoo disappeared without a trace while withdrawing from the Sea of Japan.

The loss sent ripples across the Silent Service — the name attributed to those who serve on board US submarines — as this maverick “undersea ace” would never surface again.

Morton made an everlasting impression on those he served alongside before his death, though his impressive career was not without controversy.

Mushmouth

Born on July 17, 1907, in Owensboro, Kentucky, and raised in Miami, Florida, Morton attended the US Naval Academy with the class of 1930. He became a star athlete on the football and wrestling teams. While at the Naval Academy, his fellow midshipmen nicknamed him “Mushmouth” for his heavy Southern drawl and his square jaw that resembled that of the cartoon character Moon Mullins. By the time he took command of the USS Wahoo in December 1942, his crew referred to him simply as “Mush.”

Morton initially served as a prospective commanding officer — or in sub slang, “makee learn” — aboard the USS Wahoo on a relatively unsuccessful war patrol. His observations of a cautious leadership style and demoralized crew impacted him immensely. When he assumed the role of skipper, Morton was determined to transform his bubbleheads into an aggressive fighting force. His first call to action as skipper set high expectations for the Wahoo’s upcoming third war patrol.

“Wahoo is expendable,” Morton told the crew, according to the book The Bravest Man by William Tuohy. “We will take every reasonable precaution, but our mission is to sink enemy shipping. We are going out there on this war patrol to search for Japs. Every smoke trace on the horizon, every contact on watch will be investigated. If it turns out to be the enemy, we are going to hunt him down and kill him.”

Morton paused, then informed the crew that he only required volunteers for this mission, and anyone was free to transfer. Later, when Morton asked the yeoman (ship’s clerk) whether any of his crew requested a transfer, the yeoman replied: “Not a one, Captain.”

‘SHOOT THE SUNZA BITCHES’

In January 1943, the Wahoo set sail from Australia for her third war patrol — Morton’s first as skipper. Their mission was simple: conduct “reconnaissance” of the Wewak Harbor, a major Japanese staging area in New Guinea. However, Morton’s primary motivations were clear from the start. He put up reminders in the form of placards with bright red letters in every compartment of the Wahoo. The message was clear: “SHOOT THE SUNZA BITCHES.”

The Wewak Harbor had never been penetrated by US submarines before. Although the Wahoo had no harbor charts for navigation, a sailor had purchased an Australian school atlas while in port, and it proved to be the only reference Morton needed to execute his bold plan.

Morton’s cocksure aggressiveness stood in direct contrast to the Wahoo’s previous leadership, which favored caution over kills. US submarines typically remained submerged during daylight hours, but Morton called for daytime surface patrols with additional lookouts on the bridge to better his chances of locating Japanese ships. However, Morton’s first test in combat wasn’t against a Japanese ship; instead, it came in the form of an aerial threat.

As they passed Japanese airfields, Officer of the Deck George Grider observed a Japanese aircraft in the distance. The pipe-smoking native of Tennessee, who later received the Silver Star for actions aboard the Wahoo, expected Morton to give the order to dive underwater. Instead, Morton stalled his decision until the plane was within range of 6 miles.

“Great lord,” Grider thought, “we’re under the command of a madman.”

The nearly suicidal bluff resulted in the plane veering away before Morton ultimately issued the order to dive. The delayed dive saved hours of travel time and positioned their submarine to reach the Japanese harbor sooner than expected.

Days passed before Lt. Dick O’Kane spotted the Japanese destroyer Harusame through the Wahoo’s periscope. He also spotted several Japanese submarines escorting the Harusame, allowing Morton time to plot and stage his attack.

“Few captains had enough faith in a junior officer to operate the periscope, but Morton saw something in O’Kane,” a US Naval History and Heritage Command article reads. Later in the war, Morton’s perceptions would be proven correct when O’Kane received the Medal of Honor while serving as a commander for the USS Tang (SS-306).

The Wahoo closed to within 1,200 yards of the Harusame before Morton gave the order to fire three bow torpedoes at the enemy ship. All three torpedoes missed their target. Morton fired a fourth, but it, too, missed. Morton later reported how it seemed like most of the Japanese crew on the destroyer were topside, acting as lookouts. After the four misses, the destroyer motored straight toward the Wahoo to blow them out of the water.

As the enemy ship closed in, Morton waited until the last second to fire his final torpedo. It was the first “down the throat” shot of the entire war. The torpedo hit its mark, and the destroyer was forced to beach itself to avoid sinking; thus, the Wahoo didn’t receive credit for the “kill.”

The Buyo Maru Incident

During Morton’s first war patrol as skipper, he also became the subject of a war crimes investigation. The unrestricted submarine warfare in the Pacific Theater meant that all Japanese convoys were deemed military targets. Morton had a staunch belief that, if he sank a Japanese vessel, then the survivors were still considered a threat, despite what the Hague Convention of 1907 considered a violation of international law. Morton believed surviving lifeboats would reach New Guinea, where survivors could take up arms against US land forces. He didn’t give any survivors that chance.

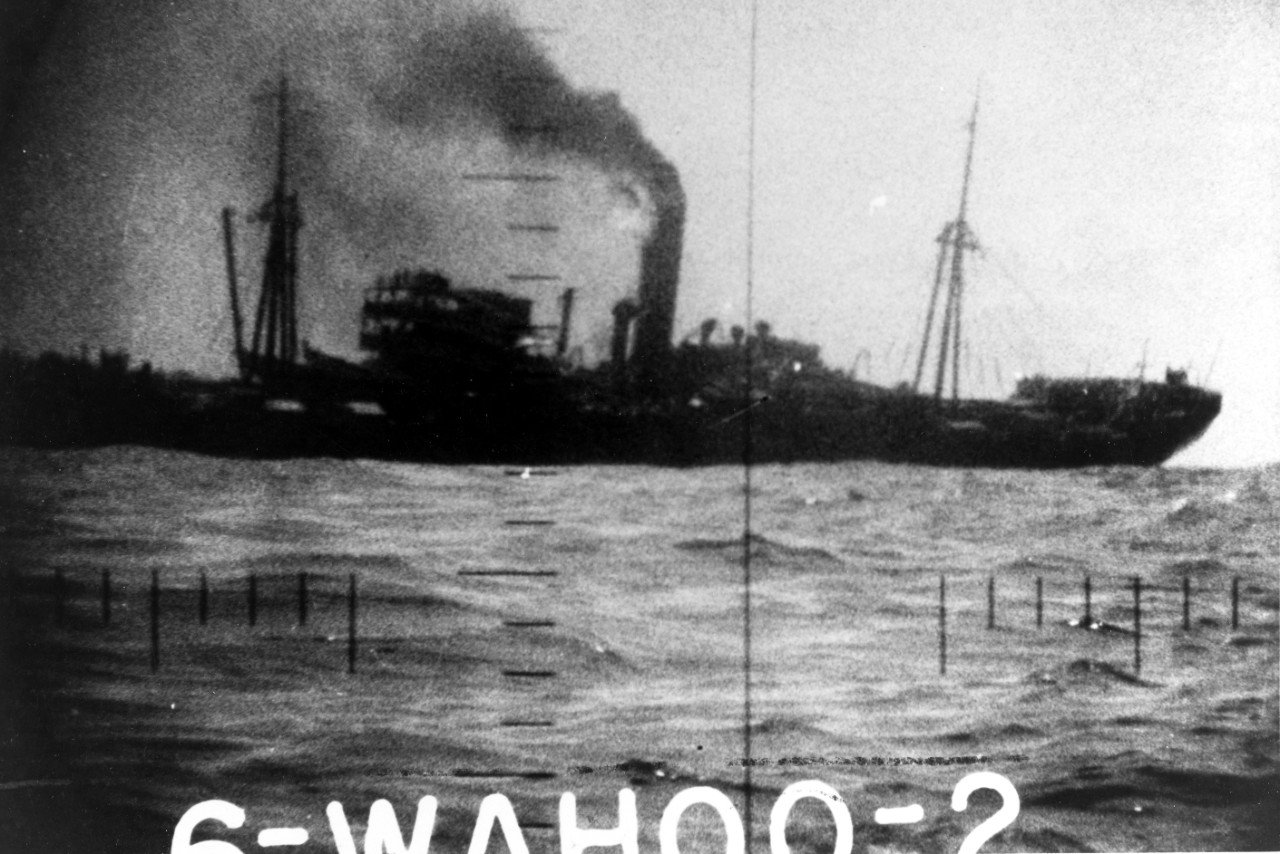

On Jan. 26, 1943, Morton, with conviction in his mind, attacked the Buyo Maru convoy. In a 10-hour onslaught, the Wahoo made a “clean sweep” of two Japanese freighters, a tanker, and a transport ship. The Wahoo then surfaced near the sinking Buyo Maru transport ship to recharge its batteries and sighted an estimated 20 lifeboats full of men with life jackets. What happened next is widely debated.

“Morton’s account admits firing on the boats, but not on individuals, and grossly over-estimated the number of Japanese troops lost in the sinking (1,500–6,000 were claimed),” the US Naval History and Heritage Command reports. “O’Kane’s account states that Morton gave the order to fire on a lifeboat to force the Japanese troops to abandon the boats, but that individuals were not targeted and the Japanese returned fire. Vice Admiral Lockwood (COMSUBPAC) reports that the Japanese army troops fired on Wahoo first with machine guns, and that such resistance was not uncommon.”

For more than 50 years, the participants believed the shipwrecked sailors were Japanese soldiers. However, the account has since revealed that many of the Buyo Maru survivors were Indian soldiers captured by the Japanese in Southeast Asia. They were en route to forced labor camps in New Guinea when Morton intervened. Among the 1,126 personnel, 195 Indians and 87 Japanese died.

The Wahoo eventually returned to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, to a hero’s welcome on Feb. 7, 1943. Morton received another nickname as “The One-Boat Wolfpack” — in homage to the legendary German U-boats that hunted the Allies in wolf packs in the Atlantic.

Lost at Sea

Morton’s additional war patrols had mixed results. On the Wahoo’s fourth war patrol, Morton sank numerous cargo ships and freighters. The most surprising attack of them all came against a 100-ton trawler. Morton fired his 4-inch and 20mm guns, but when all three 20mm guns jammed, he pulled the Wahoo alongside the Japanese ship. The Wahoo bubbleheads grabbed their homemade Molotov cocktails — gifts from US Marines at Midway — and hurled the incendiary devices into the trawler, setting the ship ablaze.

The Wahoo’s fifth war patrol took the submarine near the Kuril Islands between April and May 1943, where it sank 93,281 tons of war materials — a record for most damage inflicted on the enemy in the shortest amount of time.

The Wahoo’s sixth war patrol netted zero Japanese targets sunk. Morton credited the poor performance to faulty torpedoes. Although the Wahoo spotted 12 Japanese vessels and hunted nine, the torpedoes made erratic maneuvers when fired, missing their targets.

As a result, he requested to return to the Sea of Japan for a second time. He received orders for his final war patrol and personal vendetta against the Japanese in September 1943. The Wahoo anticipated entering the Sea of Japan alongside another American submarine, the USS Sawfish, and departing through the La Perouse Strait. However, on the return trip home, Morton and the Wahoo disappeared without a trace.

According to the US Naval History and Heritage Command, Japanese records reported the Wahoo had sunk four Japanese ships before an anti-submarine aircraft discovered their presence. The Japanese aircraft dropped three depth charges, which is believed to have sunk the Wahoo.

At the time of his death, Morton had received six battle stars, four Navy Cross medals, one Army Distinguished Service Cross, the Purple Heart, and a Presidential Unit Citation. The Buyo Maru incident has since cast Morton’s legacy into a controversial headpin regarding whether he was a brilliant underwater tactician or a bloodthirsty killer.

In 1952, Navy Cross recipient and author Cmdr. Edward Beach shared high praise for his fellow submariner.

“More than any other man, Lt. Comdr. Dudley W. Morton—and his Wahoo—showed the way to the brethren of the Silent Service,” Beach wrote. “He was positive, intolerant, quick to denounce inefficiency if he thought it existed: but he was precise by nature, absolutely fearless and possessed a burning desire to inflict damage upon the Japanese enemy.”

In 2006, a team of Russian divers discovered the Wahoo at a depth of 213 feet in the La Perouse Strait of the Sea of Japan. A memorial ceremony in 2007 at the USS Bowfin Submarine Museum & Park saw more than 200 family members and friends in attendance, bringing Morton’s saga to a close.

Read Next: Sabotage by Boy Scouts: The Only Submarine To Sink a Freight Train

Matt Fratus is a history staff writer for Coffee or Die. He prides himself on uncovering the most fascinating tales of history by sharing them through any means of engaging storytelling. He writes for his micro-blog @LateNightHistory on Instagram, where he shares the story behind the image. He is also the host of the Late Night History podcast. When not writing about history, Matt enjoys volunteering for One More Wave and rooting for Boston sports teams.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.