Max Cleland, Senator Who Lost Both Legs and an Arm in Vietnam, Dies at 79

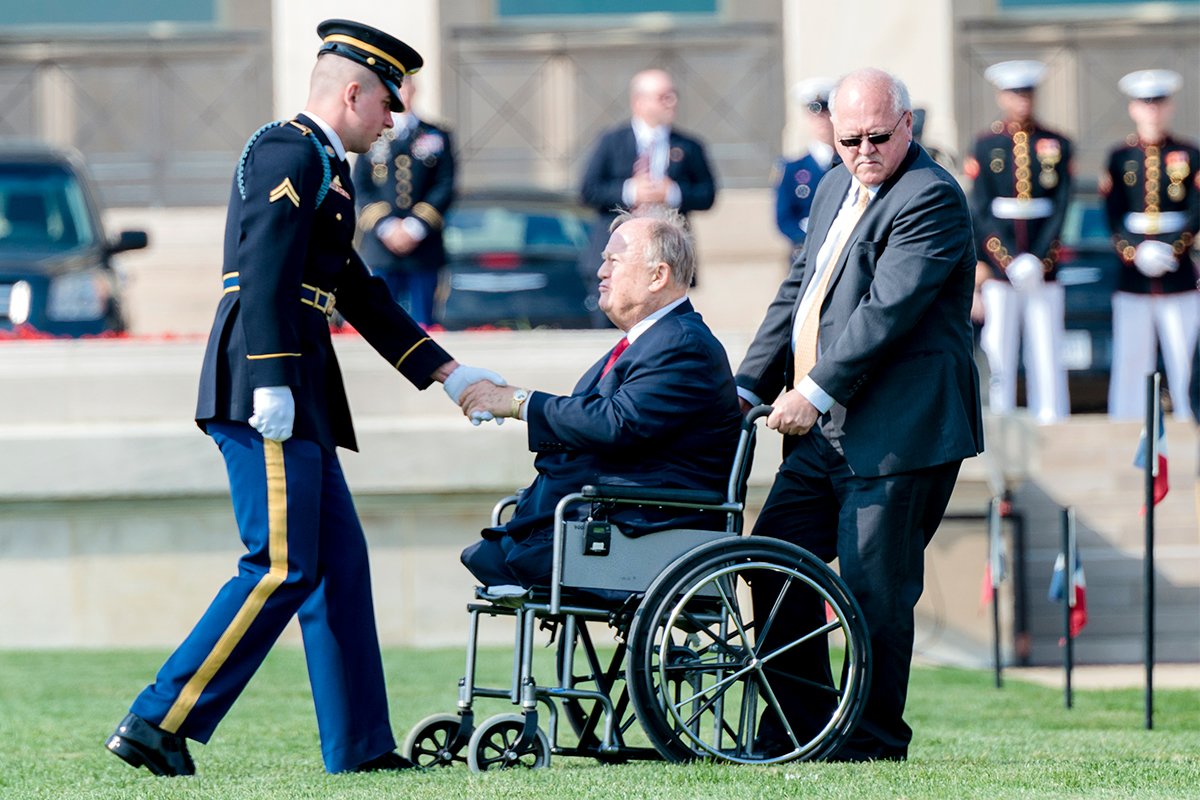

A soldier shakes hands with former Sen. Max Cleland during a National POW/MIA Recognition Day ceremony at the Pentagon River Parade Field Sept. 19, 2014, in Arlington, Virginia. Cleland served as the event’s guest speaker. DOD photo by Staff Sgt. Sean K. Harp.

Max Cleland, who lost both of his legs and an arm to a grenade in Vietnam but rose to the US Senate as a politician who championed veterans’ issues, died Tuesday at the age of 79.

Cleland, a lifelong Georgian who also served as the chief administrator of what’s now the Department of Veterans Affairs under President Jimmy Carter, died from heart failure at his home in Atlanta, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported.

After Vietnam, Cleland became the youngest Georgia state senator at 28 and was eventually elected Georgia secretary of state. He won one term in the US Senate in 1998 but lost a contentious reelection campaign in 2002.

In a statement released by the White House, President Joe Biden wrote, “Max Cleland was an American hero whose fearless service to our nation, and to the people of his beloved home state of Georgia, never wavered.”

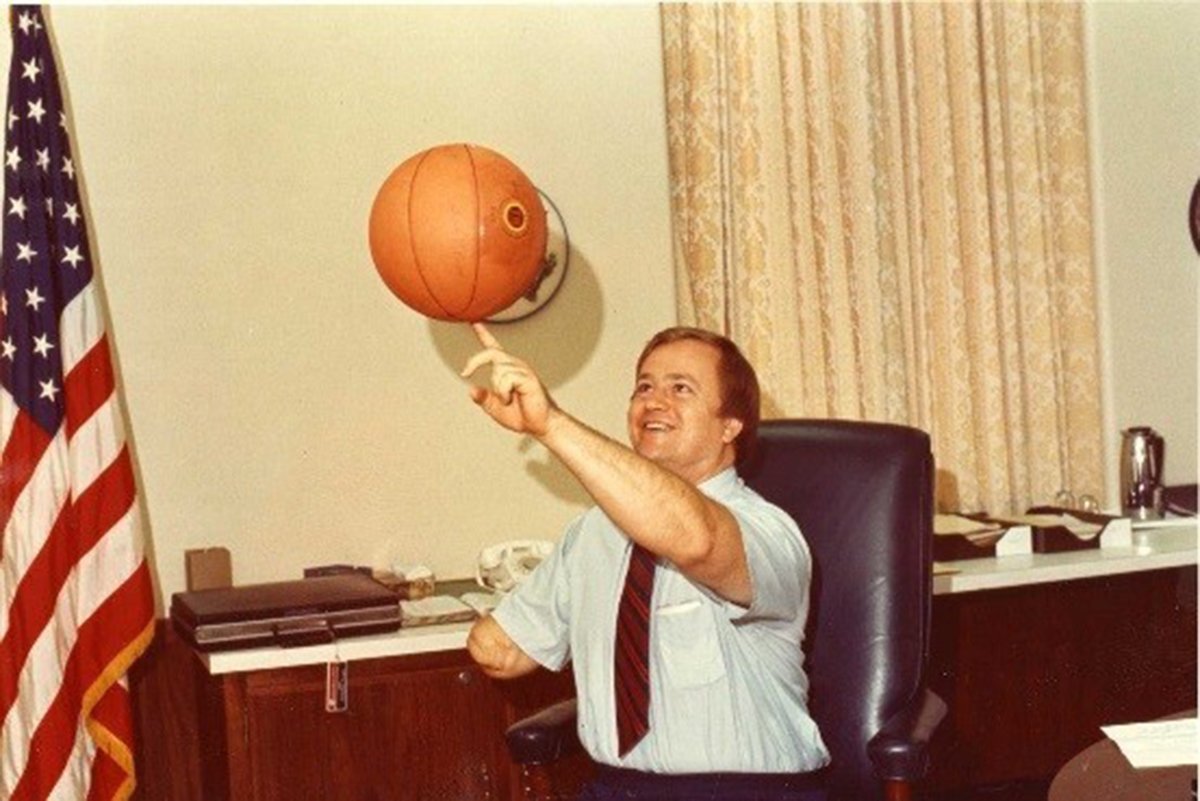

Joseph Maxwell Cleland was born Aug. 24, 1942, and grew up in Lithonia, Georgia, about 20 miles east of Atlanta. He was a star athlete, standing 6 feet, 2 inches, and used an ROTC scholarship to earn a bachelor’s degree from Stetson University in Florida. He later received a master’s in history from Emory University. A semester in Washington during his undergraduate years cemented his desire to go into politics. But first came the Army.

Cleland commissioned as a second lieutenant, completed Airborne School, and went to Vietnam in 1967 with the 1st Air Cavalry Division. He was awarded the Silver Star for actions when his headquarters was attacked on April 4, 1968. According to his Silver Star citation, when Cleland’s “battalion command post came under a heavy enemy rocket and mortar attack, Captain Cleland, disregarding his own safety, exposed himself to the rocket barrage as he left his covered position to administer first aid to his wounded comrades. He then assisted in moving the injured personnel to covered positions. Continuing to expose himself, Captain Cleland organized his men into a work party to repair the battalion communications equipment which had been damaged by enemy fire.”

Four days later, on a rescue mission in Khe Sanh, a member of his platoon dropped a grenade while exiting a helicopter. Cleland saw the grenade on the ground and picked it up to hurl it away, but it was too late.

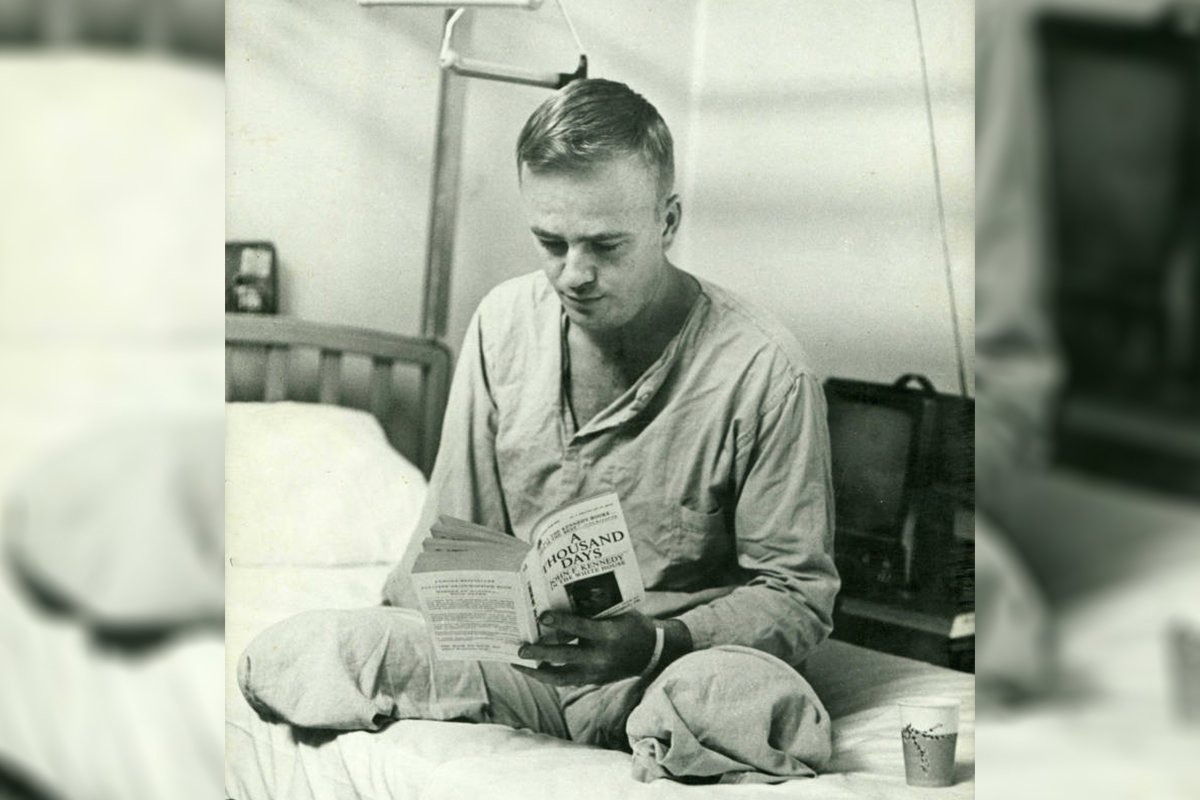

In his 1980 memoir, Strong at the Broken Places, Cleland wrote:

“A blinding explosion threw me backwards. The blast jammed my eyeballs back into my skull, temporarily blinding me, pinning my cheeks and jaw muscles to the bones of my face. […] When my eyes cleared, I looked at my right hand. It was gone. Nothing but a splintered white bone protruded from my shredded elbow. […] Then I tried to stand but couldn’t. I looked down. My right leg and knee were gone. My left leg was a soggy mass of bloody flesh mixed with green fatigue cloth. […] My hand touched my throat and came back covered with blood. Shrapnel had sliced my windpipe. I sank back on the ground knowing that I was dying fast.”

The blast claimed Cleland’s right hand and both legs.

Cleland long believed the grenade had fallen off his own belt. He only learned that it was someone else’s — a soldier who had manipulated the pin to make it easier to pull — when the Marine who tied Cleland’s tourniquet contacted him 30 years later.

The injury changed the trajectory of his life, launching him toward a political career shaped by a troubling introduction to VA care. He likened his first time visiting a VA hospital for rehabilitation to being “dropped off at a federal prison by mistake.”

“Most of the men in the ward were 20 or more years older than I,” he wrote in his memoir. “Some stared at me like I was a man from Mars. Others blinked a couple of times and rolled over on their beds. […] I had come here to get rehabilitated, but felt as if I had been sentenced to an old elephant burial ground.”

Finally, he returned to Lithonia.

“Finally got a decent set of limbs and went home in December of ’69,” Cleland said in a 2002 interview. “And I can remember sitting there in my mother and daddy’s living room and saying, ‘Well, no job. No future. No girlfriend. No car. No apartment. No money. This is a great time to run for the state senate.’”

The 28-year-old Cleland used his parents’ living room as campaign headquarters during his successful run for the Georgia Senate in 1970. Jimmy Carter was elected governor the same year. Seven years later when Carter became president, he appointed Cleland head of what is now the Department of Veterans Affairs.

During his tenure, VA doctors first recognized the existence of post-traumatic stress disorder as a disability. After President Carter was voted out of office, Cleland lost his post at the VA and returned to Georgia, where he resumed his climb in Georgia politics as a Democrat, even as his party was beginning to lose its long hold on the state’s elected offices.

He was elected secretary of state in 1983 and to the US Senate in 1996, replacing a retiring Sam Nunn. In the Senate, he focused on military issues such as expanding education benefits through the GI Bill, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported.

Cleland’s bid for reelection in 2002 is remembered for accusations by Saxby Chambliss, who was not a veteran, that Cleland was a Democrat who did not support national security initiatives of President George W. Bush after 9/11, despite Cleland’s vote to authorize the Iraq invasion. Chambliss aired a commercial tying Cleland to images of Usama Bin Laden and Saddam Hussein, painting Cleland as soft on the war on terrorism. Sen. John McCain and other Vietnam veterans in Congress condemned the ad, but Cleland lost the election.

In the years after the election, Cleland descended into what he termed long-repressed PTSD from his injuries. He spoke openly later in life of deep depression.

According to several outlets, including The Washington Post, Cleland once told military author Thomas E. Ricks, “I went down — physically, mentally, emotionally — down into the deepest, darkest hole of my life. I had several moments when I just didn’t want to live.”

In 2009, President Barack Obama appointed Cleland secretary of the American Battle Monuments Commission, which manages cemeteries and monuments in 17 countries.

Cleland left no immediate survivors, The New York Times reported, but had many close friends.

Read Next:

Hannah Ray Lambert is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die who previously covered everything from murder trials to high school trap shooting teams. She spent several months getting tear gassed during the 2020-2021 civil unrest in Portland, Oregon. When she’s not working, Hannah enjoys hiking, reading, and talking about authors and books on her podcast Between Lewis and Lovecraft.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.