SPC 4 Robert Patterson Bum-Rushed 5 Machine Gun Nests in Vietnam to Earn Medal of Honor

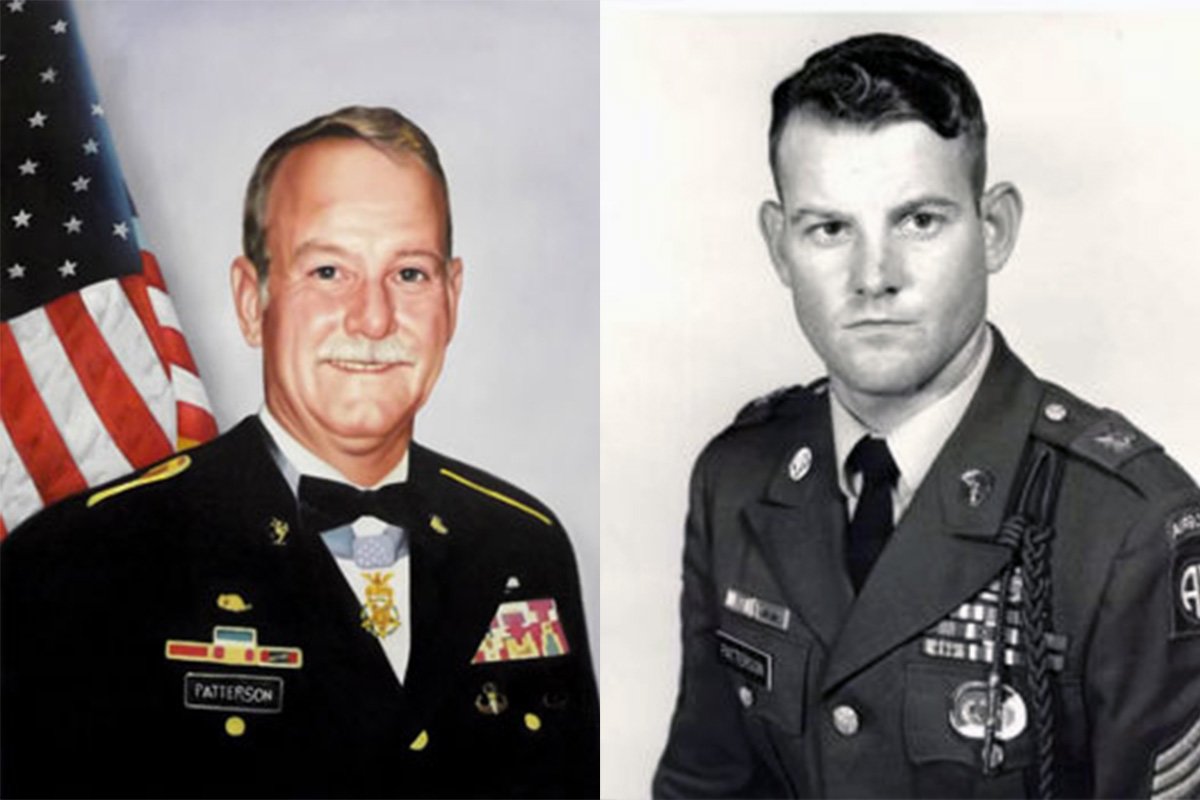

Medal of Honor recipient Robert Patterson.

The Vietnam War echoes in the soul of the United States. As one of the most divisive and misunderstood wars in our nation’s history, it was fought in large by young men who sought to uphold the honor of their nation as their fathers, uncles, and brothers had done in World War II and the Korean War. Upon their return from combat, veterans of the Vietnam War were not shown the appreciation they deserved. However, over the years, these veterans have started to receive respect and recognition.

From 1959 to 1973, the powder keg that was Vietnam pitted itself in an ideological civil war: the American-supported capitalist Republic of Vietnam in the south versus communist North Vietnam. The war produced 261 Medal of Honor recipients and a generation of men whose courage under extreme conditions continues to inspire us. Then-Specialist 4 Robert Martin Patterson is one of those heroes, single-handedly destroying five bunkers, killing eight enemy soldiers, and capturing a weapons cache during a firefight in Vietnam.

On a sunny day in October 1969, four American soldiers stood at attention on the east lawn of the White House in their Class A uniforms. Each one was going to be awarded the Medal of Honor by President Richard Nixon for their actions in Vietnam. Twenty-one-year-old Patterson, who had been promoted to sergeant after his tour in Vietnam, was annoyed that he couldn’t wear his jump boots. He was the only paratrooper of the bunch, and since the Army wanted them to be all dress-right-dress, he had to wear the standard low-quarter shoes. As the speaker read his citation detailing his acts of gallantry and intrepidity in the face of overwhelming odds against the North Vietnamese, Patterson stood bewildered — he didn’t have a single memory of his actions that day.

Patterson was born on April 16, 1948, in the small town of Carpenter, North Carolina. However, his family soon moved to Fayetteville, which is where he grew up. His father was a carpenter, and his mother stayed home to raise him, his older brother, and his four sisters. Patterson was an above-average student who often got into schoolyard scuffles with a rival boy. Since his family was poor, he started working in the tobacco fields when he was old enough.

After getting into an argument with his high school sweetheart one weekend, Patterson decided he would show her what’s up. On that Monday, he dropped out of the 12th grade, showed up at the recruiting station, and signed up for the United States Army. The year was 1966, and the Vietnam War was beginning to really heat up. Since he never bothered to pay much attention to the news, he had never even heard of Vietnam.

While at basic training at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Patterson got his first Article 15 for being AWOL. On a weekend pass, he went home to meet up with his girlfriend — yeah, those crazy kids made up. He missed accountability formation by two hours, so he spent the rest of basic on restriction and pulling extra duty.

After infantry school and jump school, he was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division but was then transferred to the 17th Cavalry, 101st Airborne Division because it needed the manpower for its mobilization to Vietnam. One day while driving his Pontiac on post, his loud muffler pissed off one of the lieutenant colonels. He was ordered not to bring the car on post until he got it fixed. But, not one who liked to be bossed around, he thought, “No one is going to tell me I can’t drive my car.” He drove it on post anyway and got another Article 15 for insubordination.

In December 1967, after some field training, Patterson’s unit deployed to Vietnam. The American strategy in Vietnam was simple: harness its overwhelming firepower and technology to kill as many enemy combatants as possible. Body count, not land, was the measure of success. Ho Chi Minh, the president of North Vietnam, cockily responded to the strategy with, “You kill 10 of us, we will kill one of you. But in the end, you will tire first.” The North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and its southern insurgency force, the Viet Cong, were avid practitioners of Mao Zedong’s style of guerrilla warfare. “Select the tactic of coming from the east and attacking from the west; avoid the solid, attack the hollow; attack; withdraw; deliver a lightning blow, seek a lightning decision.”

He was now Specialist 4 Patterson, and the Viet Cong welcomed the 19-year-old in true guerrilla fashion — by mortaring the airfield his plane was landing on. Close call, but no direct hit. The 17th Cavalry settled into Vietnam and began performing convoy escorts and search-and-destroy missions throughout the vast rice paddies of the countryside. Patterson’s unit got its first baptism by fire after the failed Tet Offensive pushed the remnants of the Viet Cong out of Saigon in early 1968. Patterson’s unit was positioned on the outskirts of the city, on top of two hills. The unexpecting enemy troops were retreating between the two hills and were mowed down. The Americans suffered no casualties; a good day’s work. Being a Cavalry unit with gun jeeps packing a ton of firepower, they were constantly asked to bolster up infantry units who were engaged with the enemy.

On his own, he systematically repeated the same mad dash and flanking maneuvers on the next bunker. … He accomplished this insane feat a total of five times.

On May 6, 1968, in La Chu, they were tasked with another day of search and destroy. Since Patterson was lower enlisted, he was left out of the know. Headquarters had received intel that a regiment of NVA was out in the area. Patterson and his buddies had a sneaking suspicion that something bigger was going because, in addition to their platoon, all of Troop B plus two additional Troops were part of the sweep. With over 200 paratroopers, and unbeknownst to him at the time, this was the mission that would earn Patterson the Medal of Honor.

At first, it seemed like the same ol’ shit, different day. He was a fire team leader with two men underneath him, privates Alfredo Vega and Henry St. Johns, in 3rd Squad, 3rd Platoon. At 8 o’clock in the morning, they were stomping like jolly green giants through farmlands in search of enemy hiding spots and ammunition caches. Cobra helicopters flew overhead, scanning the area and ready to unleash hell upon NVA or Viet Cong soldiers; artillery was on standby awaiting a fire order. Patterson’s platoon was spread out in a long line along a bend in the river.

At 1 PM, two spider holes opened machine gun and RPG fire on 3rd Platoon, ruthlessly and effectively eliminating the entire leading squad. The rest of the platoon hit the ground and was pinned down. The platoon sergeant, Sergeant First Class George Simmons, signaled to 3rd Squad to take out one of the bunkers as he and two other men dashed toward another bunker. The squad leader, Sergeant Alex Gray, had Patterson’s fire team join him in flanking the enemy position, where they killed all the occupants. Simmons and the two other men were severely wounded after killing one of the NVA and failing to flush out the rest of the fortified position. The image of his platoon sergeant laying six feet in front of the bunker was the last clear memory Patterson had for the next four hours.

Patterson and Gray attempted to flank the bunker that had struck down their platoon sergeant. As they were approaching, Patterson saw an RPG peering from another bunker across from them.

“Sarge, we’ve got to get that RPG!” Patterson yelled as he dashed through the field without regard for his own safety. A total of five bunkers opened up a withering stream of intersecting fire upon him.

He was a man possessed. Bullets were cracking all around him as he radiated a supernatural invincibility through the gauntlet of death. He had mustered such a deep rage that it struck fear into the heart and soul of the RPG gunner, making his aim unsteady and preventing him from shooting. Patterson closed in on the bunker and made a sharp turn to get into a blind spot. He tossed a grenade into the bunker’s firing slit and annihilated the three NVA inside.

Herring told him that it was much harder to wear that ribbon than to earn it. ‘And he was absolutely correct. It totally changes your life.’

One down. He was still receiving fire from the other bunkers. On his own, he systematically repeated the same mad dash and flanking maneuvers on the next bunker. The NVA, unable to get a single clean hit on this crazy white devil, fired recklessly. He encroached on the second bunker and threw a grenade into its firing slit — second one down. He accomplished this insane feat a total of five times.

His next clear memory was at 5 PM. His platoon was inside a 500-pound-bomb crater. There was a dead soldier lying next to him, a new guy he didn’t know well. Vega from his fire team was wounded. Patterson only had a few shrapnel wounds. The Cobra helicopters were laying down America fury on the NVA. Artillery rounds were thundering from a distance, hoping to destroy the retreating NVA regiment. The 3rd Platoon set up a defensive perimeter and stayed there all night.

Patterson was called into the general’s office the next morning and was awarded the silver star. “What for?” he wondered. “I didn’t do nothing.”

After putting the medal away in his rucksack, Patterson was back to search and destroy, as usual, the next day. While the unit got into more firefights during that deployment, it was never as intense or ferocious as the day they took on an NVA regiment three times their size. Patterson returned to the United States in December 1968 as a sergeant.

In September 1969, Patterson was summoned to division headquarters and told that he would receive the Medal of Honor for his actions in Vietnam.

Patterson made a career out of the military. After the Vietnam War, he spent the 1970s as a drill sergeant at Fort Bliss, Texas, molding the next generation of soldiers. He eventually made the rank of command sergeant major and served in the first Gulf War before retiring in 1991. Afterward, he worked for the Department of Veterans Affairs for 12 years. He now lives with his wife and family in Pensacola, Florida.

Though he knew nothing about Vietnam or the Medal of Honor when he enlisted in the Army on a whim, they both completely changed his life.

“I think that a person who wears the Medal of Honor is not wearing it for themselves. They’re wearing it for everyone who was there,” Patterson said during an interview with the Veterans History Project. “Particularly for those who didn’t come back. Everything I do, before I do it, I will stop and think if it is going to embarrass that medal. Is it going to bring any kind of disgrace on it at all? If it is, then I won’t do it. And so it, it kind of controls you in what you do. And that’s probably — it’s a good thing. Because I would have probably gotten into some scrapes or done some things that I shouldn’t have done had I not had it.”

He recalled a conversation with Rufus “Geddie” Herring, who was a World War II Medal of Honor recipient, where Herring told him that it was much harder to wear that ribbon than to earn it. “And he was absolutely correct,” Patterson said. “It totally changes your life.”

Raul Felix is a 32-year-old Mexican-American from Huntington Beach, California. He currently lives in Long Beach. He served in the United States Army from 2005-2009. Raul writes about sex, dating, women, military life, manhood, Mexican-American culture, motorcycle travel, and anything else he pleases. He currently attends college, bartends, and writes. He has been a featured writer on Thought Catalog. You can find all his written work at RaulFelix.com. He’s on a quest to be one of the greatest writers of our era. You can reach him at [email protected].

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.