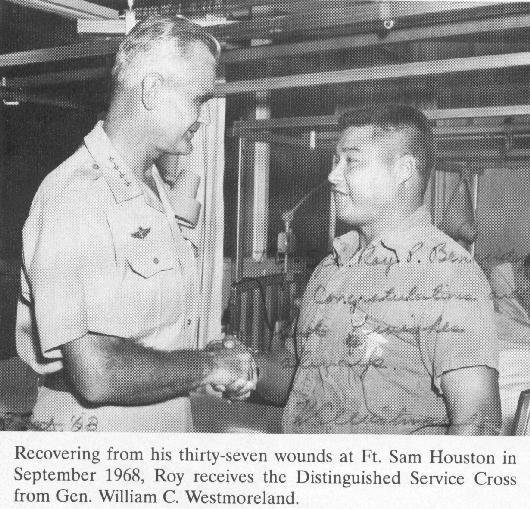

President Ronald Reagan presenting the Medal of Honor to Sgt. Roy Benavidez at a ceremony at the Pentagon on Feb. 24, 1981. Photo courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

During the Vietnam War, 235 Medals of Honor were awarded, and another 26 have been retroactively awarded to those who served in the war but weren’t recognized at the time of their actions. These U.S. Marines, soldiers, sailors, and airmen risked their lives for the mission and the men to their left and right, going above and beyond the call of duty. Tales of their heroism inspire young servicemembers to this day.

On one fateful day in Vietnam, Master Sergeant Roy Benavidez became a special operations legend with actions that ultimately resulted in him receiving the Medal of Honor.

Born in 1935 in the rural Texas town of Lindenau, he was the child of a Mexican-American farmer father and a mother who was a Yaqui Native American. Tragically, his father died from tuberculosis when Benavidez was 3 years old; five years later, the same ghastly sickness struck down his mother. On the day of their mother’s funeral, 8-year-old Benavidez was unsure of how he and his brothers would be cared for. His uncle, whom he had never met, took them in and raised them in El Campo, Texas.

Along with his nine new brothers and sisters, Benavidez spent the rest of his adolescent years working in the beet fields and other odd jobs to contribute to his family’s income. The shadow of Jim Crow still loomed across the land, and signs reading “No Mexicans or Blacks” at various establishments created a deep resentment within him.

The work in the field made him miss four months of school a year, and it proved to be a constant struggle to keep up. He was placed in remedial classes, which mostly consisted of Mexican children, and that prompted some of the white kids to taunt him as a “dumb Mexican.” That phrase enraged him so much that he’d harness the strength built in the fields to crush the faces of those kids in the school yard. The principal’s office became his second home.

At age 15, Benavidez dropped out of school to work full time — something that later brought him great shame.

Benavidez was haunted by the memories of Vietnam, and he wanted to go back — he knew his place was as a frontline soldier, and the war over there was still raging.

While working at a tire shop, Benavidez joined the Texas National Guard. After three years, he went on active duty in the U.S. Army. He was sent to Korea to pull security duty in the demilitarized zone after the Korean War had ended, and then he was sent to Germany. While home on leave, he married Hilaria “Lala” Coy, who he had been writing letters to since his early days in the Army. Benavidez dreamed of earning his jump wings and finally got the opportunity after being assigned as General William Westmoreland’s driver.

He was proud of the silver airborne wings on his chest, and like the paratroopers from the World War II newsreels he watched as a young boy, he reported to his new unit: the famed 82nd Airborne Division.

In October 1964, Benavidez was among the first 125,000 American troops in Vietnam. Working as a military advisory alongside Republic of Vietnam soldiers, he helped train them in American military tactics. One day, while on patrol, he stepped on and triggered a land mine.

Where the humid and tangled jungles of Vietnam had once surrounded him, now the white walls of Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas, stood.

The blast wiped his memory clean, and the paralyzation that ensued made even the simplest movements painful or impossible. He was told he would never walk again. A dark cloud of despair hung over Benavidez as he looked over his broken body and contemplated life in a wheelchair — no longer useful to the Army and a burden on his family. He begged the doctor not to release him from the military, to just give him a little more time to recover.

Benavidez knew he had to take matters into his own hands. One night after the nurses made their rounds, he began to crawl from his bed across the floor of the ward. He only made it a couple of feet in his first attempt. But over the next few months, he slowly rebuilt his strength enough to not be medically discharged. He was given an administrative job.

Benavidez was haunted by the memories of Vietnam, and he wanted to go back — he knew his place was as a frontline soldier, and the war over there was still raging. He quietly devised a plan to join the ranks of the Army’s new elite unit: the Special Forces. Over the next year, he rebuilt his body and mind by working out consistently and studying the field manuals that were taught in the Special Warfare School. In order to get himself back on jump status, he used his knowledge of the Army’s bureaucracy to get himself into a perfectly good airplane to jump out of.

He submitted his paperwork and was admitted into Special Forces selection. Though the training and workload was extremely tough, he earned the coveted Green Beret.

Less than four years after he was nearly medically discharged from the Army, Benavidez was on his second tour in Lộc Ninh province in Vietnam as a Special Forces NCO. Benavidez’s radio call sign was Tango Mike Mike, or That Mean Mexican as his teammates lovingly called him.

This tour was proving to be anything but boring. Three days prior, he had narrowly escaped death yet again thanks to teammate Sergeant First Class Leroy Wright, who managed to keep him from falling off a helicopter as they were exiting a hot helicopter landing zone (HLZ).

Without time to go get his rifle, Benavidez boarded a different returning helicopter armed only with his knife and a medical bag…

On May 2, 1968, he was off duty and listening to a sermon from the chaplain when he overhead some radio chatter and walked over to the communications stations to see what was going on. A 12-man Special Forces patrol, comprised of three Green Berets and nine Montagnard tribesmen had been surrounded by over 1,000 North Vietnamese infantry. All 12 of the men had suffered serious injuries. Benavidez ran to the helipad to greet the bullet-ridden helicopters that had failed to extract the soldiers.

The door gunner, Specialist 4 Michael Craigs, had been shot several times and fell into Benavidez’s arms. “Oh my god, my mother and father,” were the 19-year-old’s last words.

As Benavidez comforted the distressed pilot, he asked him who was out there.

“It’s that black feller who’s on your team,” said the pilot, referring to Wright.

Without time to go get his rifle, Benavidez boarded a different returning helicopter armed only with his knife and a medical bag — he knew there would be weapons on the ground to use once he got there. All the knowledge he had accrued throughout his rough life and challenging military career kicked in. He descended into the pits of hell for six hours.

The enemy fire was so furious that his helicopter had to fly in a zig-zag pattern while unleashing a stream of American fury on the Viet Cong — or “Charlie,” as soldiers commonly referred to them. In order to prevent disorientation when he touched down, Benavidez told the pilot to fly out in the direction of the team. As he was dashing toward them, a bullet hit him in the right leg, though he thought it was the prickling of a thorn.

He came to Staff Sergeant Lloyd “Frenchy” Mousseau, who was firing back at the enemy despite having one of his eyes hanging from the socket and wounds to the stomach. A couple of the tribesmen had been killed, and everyone on the team had been wounded in one way or another. Benavidez dragged the injured soldiers into a defensive position and applied medical aid.

He was still searching for Wright when he saw Specialist 4 Brian O’Conner a few dozen yards away with the tribesman’s interpreter and motioned him over. A hail of bullets flew all around, and they were forced to hit the ground and low crawl. Benavidez popped a smoke grenade to signal an extraction point to the helicopter. As it hovered overhead, the chopper let loose on the enemy with a heavy barrage of machine gun fire.

“You can either crawl, walk, or drag yourself, but this is the last bird out of here,” Benavidez yelled to his men.

Benavidez carried those too injured to walk to the HLZ while laying down suppressive fire. He knew he couldn’t leave Wright behind, so he ran back into the rampant jungle and found his dead body. As Benavidez dragged Wright’s body toward the helicopter, he was shot in the back. Almost simultaneously, a hand grenade exploded, peppering him with shrapnel and knocking him out.

Benavidez awoke to a greater hell. Unable to carry Wright, he was forced to leave his buddy behind. He made his way to the helicopter only to see the smoldering inferno of the wreckage. The pilot of the helicopter, Warrant Officer Larry McKibbens, had been shot and killed. Fortunately, the other passengers survived.

Knowing that the smoke would attract the enemy, Benavidez grabbed a rifle and shot up the communications systems so they couldn’t get access to the military radio frequencies. He then ordered everyone to move in the opposite direction to hide in the jungle and set up a defensive perimeter. They had evacuated just in time — mortars zeroed in on the smoke and started raining down on the crash site. From their new position, Benavidez directed several deadly air strikes against the swarm of Viet Cong attacking them.

Another chopper came in and tried to extract them, but they were shot down, too. The crew survived and joined the rest of the team in their defensive position. One last attempt was made by a new helicopter, manned by a crew of four officers.

“You can either crawl, walk, or drag yourself, but this is the last bird out of here,” Benavidez yelled to his men. He was carrying Mousseau when a North Vietnamese soldier came at him with a bayonet and slashed his arm open. Benavidez took a jaw-breaking hit with the butt of a rifle before reaching down, unsheathing his knife, and stabbing the soldier to death. He then shot two more enemy soldiers who were charging the aircraft.

He was the last one off the battlefield; once aboard the helicopter, his intestines spilled out and he passed out.

He awoke to the distinct zipping of a body bag — he was thought dead. Blood had crusted his eyes shut, he was unable to move his jaw, and he couldn’t move his limbs from all his injuries.

“There is nothing I can do for him,” said the doctor upon looking at his seemingly lifeless and war-ravaged body. As he took a closer look, Benavidez made the luckiest shot of his life. Gathering all of his strength, he spat in the doctor’s face. Laughing, the doctor corrected himself: “I think he’s going to make it.”

Master Sergeant Roy Benavidez was awarded the Medal of Honor by Ronald Reagan in 1981. He appreciated being called a hero but said, “The real heroes are the ones who gave their lives for this country. The real heroes are our wives and mothers. The real heroes are the ones who are disabled in those VA hospitals. The real heroes are our future leaders who are staying in school and saying no to drugs.”

Benavidez died on Nov. 29, 1998, after dedicating the remainder of his life to causes supporting disabled veterans and instructing children on the importance of staying in school and getting an education.

Raul Felix is a 32-year-old Mexican-American from Huntington Beach, California. He currently lives in Long Beach. He served in the United States Army from 2005-2009. Raul writes about sex, dating, women, military life, manhood, Mexican-American culture, motorcycle travel, and anything else he pleases. He currently attends college, bartends, and writes. He has been a featured writer on Thought Catalog. You can find all his written work at RaulFelix.com. He’s on a quest to be one of the greatest writers of our era. You can reach him at [email protected].

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.