Inside the Albanian Compound of an Exiled Iranian Opposition Group

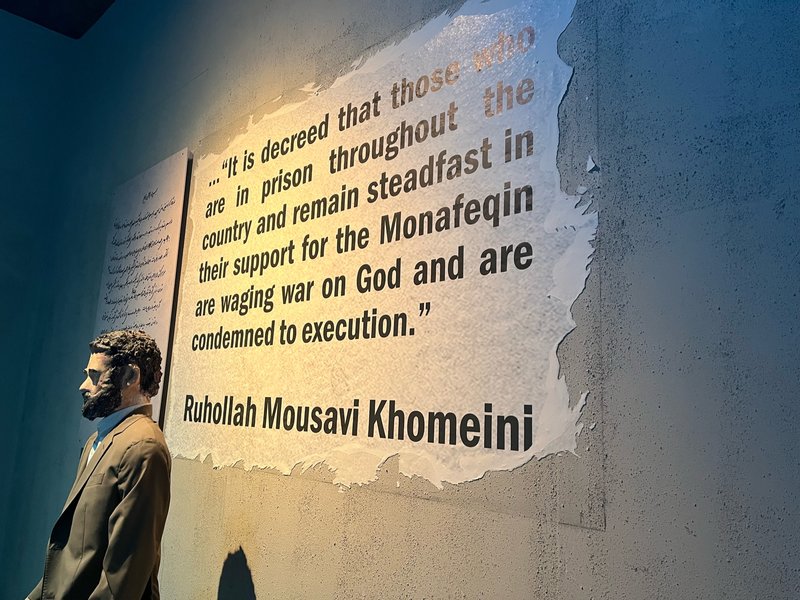

Scenes of the execution of MEK members inside Iranian prisons are re-created in a museum inside the group’s Ashraf 3 compound in Albania. Photo courtesy of Hollie McKay.

DURRES, Albania — It is the stuff of wild nightmares.

“I was a university student, almost seven months pregnant when the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps came,” remembers Kobra Jowkar, now 59. “They raided our home at midnight and were very ruthless.”

The IRG soldiers saw her bulging belly, she says, and yet still kicked her around like a football — even walking on her stomach. Then they took her to Evin prison, north of Tehran, the infamous compound where Iran has sent its political prisoners for decades. There, she says, guards mauled her with cables and sticks in front of her husband, who could do nothing but watch, motionless, unable to protect his young wife and unborn first child.

Their crime? They were suspected of supporting the Mujahedeen-e-Khalq, better known by its Farsi-language abbreviation, MEK.

An Arch of Victory at the entrance of Ashraf 3. The two lions on top are symbols of Iran’s safekeeping and go back thousands of years. Photo courtesy of Hollie McKay.

Jowkar says that her husband was executed in the dilapidated prison courtyard, one of thousands of MEK members and supporters purged, and that she gave birth inside in a cell with the help of a fellow prisoner around her mother’s age.

The loss and the psychic scars remain.

“My son is a grown man now, an engineer in Sweden, but he has had to undergo an operation for his pelvis and one leg that was growing shorter than the other,” Jowkar says, adjusting her neatly tied silk headscarf, shifting uncomfortably like a young girl herself.

Jowkar’s son was hardly the only child to grow up within the many penitentiaries scattered across Iran in the tumultuous decade following the 1979 revolution. Dozens of newborns, Jowkar says, were born to malnourished mothers behind bars. She breastfed other infants when their mothers could not, she said.

Today, Jowkar lives in a sprawling compound in Albania known as Ashraf 3. The compound is named for Ashraf Rabiei, the wife of one of the MEK’s early leaders, Massoud Rajavi. Rabiei was killed in a shootout with IRG soldiers in 1982. Rajavi disappeared in 2003, but his third wife, Maryam Rajavi, is the public face of the MEK and its associated political arms, appearing at international conferences with American political leaders. Posters and memorabilia of Massoud Rajavi remain a touchstone of the group.

Kobra Jowkar keeps pictures of family and other members of MEK who were killed in Iran during the Islamic Revolution. Photo courtesy of Hollie McKay.

Ashraf 3 is the third settlement that MEK refugees and their families have built over the decades since they fled Iran. The group built two camps in Iraq that enjoyed protection from the US after its 2003 invasion of the country. But when the US began to cede control, Iran-friendly groups forced them to flee again to Albania.

The elder generation has now spent a full lifetime both planning and hoping to return to Iran, knowing they might never be able to do so. They were, in their youth, a band of early Iranian resistance. Today, they hold a collective memory of the terrors of the Iranian regime’s early days and campaign in Western nations to highlight the regime’s crimes.

Though a small group, they are still hunted by the Iranian government. Albanian officials say they have foiled plans to attack the camp by Iranian agents, and police in Germany, France, and Belgium stopped an Iranian plot to bomb an MEK rally outside Paris.

The Forward Observer visited the MEK’s Albanian compound for a rare look at how the group lives and to hear the stories its senior members remember from the 1979 revolution.

A long driveway leads to the bivouac on the sleepy outskirts of the capital. As the call to prayer rings out, the aroma of Persian cooking wafts through the streets. In honor of the dead, there are Iranian flags everywhere and memorials dotted with red poppies, as well as a large museum. The self-sustained camp resembles a small city, complete with dwellings for the several thousand residents, a gymnasium, bakeries, and a grocery store.

There are no children in Ashraf 3, as devotees say all their energy and attention should focus on overthrowing the hard-line Iranian leadership. Day and night, women and men — from young to the old — move about carrying clipboards and backpacks, maneuvering from meeting to meeting. From their purview, there is no room for reform.

Inside the Ashraf 3’s Museum of 120 years of Struggle for Freedom. Photo courtesy of Hollie McKay.

“It is a war over human dignity,” asserts another survivor, Hossein Farsi. “When I was released, I could not convince myself to go and have an ordinary life.”

The former prisoners, all with a calm demeanor, carry brightly colored folders filled with pictures, memories, and stories of the dead. Their goal is to spread awareness of their group to the West, and to reach the ears of Western governments. Followers also point to Maryam Rajavi’s “10-point plan” — evolved from their initial leftist ideology into a system of “democratic values” — vowing that their vision of Iran is a country centered on the separation of church and state, religious freedom, gender equality, and an end to Shariah.

“This regime will end,” professes Mohammad Mohaddessin, chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the National Council of Resistance of Iran, the umbrella outfit the MEK falls under. “They have lost their popular base; people are fed up.”

The MEK began as a revolt against the dictatorship of Iran’s last Shah in 1965, espousing left-leaning Marxist rebellion ideologies. Though it shared the shah as a common enemy with Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic Republic, the leftist worldview of the MEK was in sharp contrast to Khomeini’s Islamist visions. When the shah fell in 1979, the MEK became one of the few threats to Khomeini and his Revolutionary Guard Corps’ power, with nearly as many followers.

The MEK was no early friend of American influence in Iran. In the 1970s, members of the group are believed to have planted bombs at the offices of US companies in Tehran, killing as many as six Americans (MEK officials still deny involvement). Some members of the group also supported, and are suspected of participating in, the takeover of the US embassy in Tehran and the holding of hostages there for 444 days. MEK leaders today disavow any connection to the takeover.

But even as the hostages were released, violence was erupting between factions within the MEK and the forces of the new Islamic regime. A decade of persecution followed as the Islamic Republic tightened its grip on Iran, beginning in the early 1980s.

On Aug. 10, 1981, Hengameh Haj-Hassan, now 65, worked as a nurse in Tehran under the new regime. Although a devout Muslim who wore a scarf over her head, she recalls taking to the streets in 1980 to protest a new hijab mandate.

A replica of Gohardasht Prison, built based on recollections of surviving MEK members. The replica was used in court in Sweden during the trial of Hamid Noury, a deputy prosecutor at the prison who was directly involved in the 1988 massacre. Photo courtesy of Hollie McKay.

“If a woman did not observe the veil, [the authorities] splashed acid on them or cut their face with razors,” Hassan says. “Some even received a thumbtack through the forehead to make sure the scarf was kept on their head.”

Soon, religious police wielding clubs also dragged young medical professionals like

her into the Evin prison, she says. Within the notorious gulag, guards took Hassan for interrogation, and the beatings began immediately.

“There were many women, and I saw they all had calves lacerated,” she recalls. “I thought they had been shot in the leg. But I later found out everyone had been flogged with cables. I couldn’t believe my eyes — that a Muslim government was doing this to other Muslims.”

Detainees describe being routinely transferred from prison to prison, over the course of years behind bars. For Hassan, the most gut-wrenching moment buried deep in her graveyard of memories was when a 6-month-old baby was taken away for “medical help” and never returned.

“The mother was crying and asking for her child,” Hassan says, her voice cracking. “It took them a long time, but eventually guards finally told her that her child had died but nobody knew how and they let her see him.”

When the topic of sexual violence is brought up, the group of five female survivors huddle together. Dressed in a sort of uniform of blazers with knotted navy and red headscarves, they seem to drift into dream-like states. One victim slowly stands and begins pacing aimlessly around the room, unable to sit idly as the stories are brought back to life.

Hassan describes an incident in which a young woman threw herself out of the cell window after allegedly being raped.

Iranian flags and memorials with red poppies located outside the Ashraf 3 museum in Albania. Photo courtesy of Hollie McKay.

“Another time, 15 or 16 guards took one very beautiful girl into a room, and you could hear her screaming,” Hassan tells me, with bitterness creeping into her gentle voice. “They wanted to make sure she didn’t die a virgin. So then she was executed.”

Often, torture victims recount the modes of torture they endured with a kind of distant stoicism, as if talking about a life that isn’t really theirs, as if to separate themselves from the flood of muscle memory. In Hassan’s case, she chronicles the brutality of being blindfolded and summoned inside “the cage” — a narrow enclosure just big enough for her body to curl into with her head hung low.

She says she remained there for eight months, allowed to shower on rare occasions, and let out just long enough to pray.

“In the beginning, I thought there was construction happening outside,” Hassan says with a long pause. “And then I was told that was the sound of a firing squad.”

Many survivors point to one individual as the central figure in the decade of terror: Ebrahim Raisi, the current president of Iran. Beginning in 1985, Raisi was the deputy prosecutor and then prosecutor of Tehran. Raisi led a relentless campaign against groups suspected of opposing the new Iranian government, with the MEK at the center of his crosshairs. He ran trials, widely viewed as shams, which often ended in immediate execution of the accused by firing squad or at the gallows. Inmates dubbed Raisi “The Butcher.”

In 1988, Raisi led or authorized a five-month killing spree in a massacre that Amnesty International says killed at least 5,000. In a decade of killings, MEK officials estimate that perhaps 30,000 of their members were executed without trial or on the flimsiest of legal pretenses.

Pavin Pour-Eghbal was 15 when she was apprehended, she says, and only made it through years in the prison system because she was “not brave enough to defend [her] cause.” Those who were — refusing to denounce their dissident ideology — are etched into her consciousness.

“I remember [guards] giving the belongings of executed prisoners to families,” Eghbal says. “But they didn’t give them a place of burial.”

Akbar Samadi, now 55 years old, with a pinched face and listless hands, says he wanted to demonstrate in the street as a teenager in response to the “unjust distribution of wealth in society.”

The Ashraf 3 compound in Albania. Photo courtesy of Hollie McKay.

There was the ominous “corridor of death,” the haunting hall where prisoners lined up, bloodied and blindfolded, waiting for their execution orders. Samadi believes he only survived after a face-to-face encounter with Raisi because his death sentence mandate was left on the table, and his name was never called.

“Every half an hour, they would call a group of names and take them. One time, they read a name, and the guard became very anxious because the person did not answer, and they realized they had executed a person with a similar name by mistake,” Samadi says.

“Because my name wasn’t there and they did not know what to do with me, I was sent to solitary confinement instead.”

As an example of the many torture methods used, Samadi claims he was forced on multiple occasions to stand for three whole days with his arms raised until his joints locked, and his blood vessels swelled and almost burst.

“They wanted to force you into betraying your friends or make you go totally crazy,” Samadi says.

According to a 2016 Human Rights Watch report, the 1988 killings were “a grim nadir in Iran’s recent human rights record,” in which political prisoners were not even granted the “formalities of a show trial” and scores were “summarily executed” after having languished in jails for years.

Other human rights groups, such as Amnesty International, also point to the regime’s endeavor to “erase the 1988 massacre from memories.”

Mahmoud Royaie, a survivor of the Iranian regime’s gulags after the 1979 revolution. Photo courtesy of Hollie McKay.

“Amnesty International urges the Iranian authorities to uphold the right to truth,

justice and reparation of the families of those killed in what will remain known to Iranians as the ‘Prison Massacre,’” the organization wrote in a 2013 statement.

In 2021, Raisi was elected as the new president of Iran — hand-picked by the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. Raisi’s elevation was generally viewed as the regime’s shift to a more hard-line government.

MEK remains a designated terrorist organization in Iran and was classified as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) in the United States for 15 years. In 1997, the Clinton administration slapped MEK, which had a Washington office at the time, with the label — along with 29 other foreign groups — essentially freezing its assets and initiating travel bans on its members. This was widely considered a “goodwill gesture to Iran,” in which Tehran pledged to label the growing Lebanese militia Hezbollah with the same terrorist title on its turf, only that promise was broken.

Even during its time as an FTO, however, members of MEK were deemed “protected persons” by Washington under the Geneva Convention, given that a large swath of its members — who would have faced death in Iran — had fled to Iraq, aligning themselves with the government of Saddam Hussein during his war with the Iranian regime. The group founded the Ashraf 1 and Ashraf 2 camps on the edges of Baghdad.

The MEK’s evolution as a US-aligned dissident group was propelled by Saddam’s ouster after the US invasion in 2003. The encampments came under the protection of the US military, and American troops instead stood guard at the gates.

But after the protection designation expired in 2009, the US handed full sovereignty to the Shiite-dominated new Iraqi government, then led by Nouri al-Maliki. As a result, the MEK was soon in the line of fire from their new “protectors,” Iraqi forces with ties to Tehran. Bombs and bullets rained down on the unarmed compounds in 2012 and again in 2013, killing dozens. Iraqi forces assaulted the camps, survivors say, taking hostages.

In Washington, the MEK made allies with anti-Iran Republicans, who lobbied to have the group removed from the State Department’s list of terrorist organizations in 2012.

In 2016, the group built Ashraf 3 in the quiet plains of the Albanian countryside, welcomed by the government in the Albanian capital of Tirana as it sought closer ties with Washington.

Yet still, 1,750 miles from Tehran, the threats remain. Albanian police unearthed what they believe was an “active terrorist cell” operated by a foreign wing of the IRG, intent on attacking MEK members on Tehran’s orders. Authorities said at the time they had foiled several planned assaults on the group, subsequently straining diplomatic ties between Tirana and Tehran.

Many international leaders, including representatives of the Trump administration, attended Free Iran 2018 — The Alternative, organized by MEK in Villepinte, near Paris, June 30, 2018. Front row, beginning fourth from left: Maryam Rajavi, MEK co-leader; Rudy Giuliani, then an advisor to President Donald Trump and a member of his legal team; and former US Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich. Photo by Zakaria Abdelkafi/AFP via Getty Images.

Today, the MEK enjoys influence in Washington’s foreign policy and lobbying circles. The organization gained prominent footing under the administration of President Donald Trump, given the administration’s push to isolate Tehran from the international playing field through a “maximum pressure” campaign with support from the likes of Trump’s national security advisor John Bolton, as well as Rudy Giuliani and Newt Gingrich.

In 2018, The New York Times ran a story headlined “M.E.K.: The Group John Bolton Wants To Rule Iran.” That same year, Bolton, Giuliani, and Gingrich attended the group’s annual convention in Villepinte, outside Paris, held under the banner of the MEK’s political wing, the National Council of Resistance of Iran.

But the event made headlines for a foiled Iranian bomb plot. An Iranian diplomat in Brussels was arrested and sentenced to 20 years in prison for attempting to smuggle explosives into the event.

Today, the MEK may hold less sway in the Biden White House, as the administration negotiates with the Iranian regime to restart the Trump-abandoned nuclear treaty, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

Those in Ashraf 3 maintain that their revolution is nonviolent and say they believe in “small steps” inside their country. On Jan. 27, 2022, disruptors briefly hacked state-controlled television channels simultaneously with images of the Rajavis.

A few weeks earlier, with much fanfare to mark the second anniversary of his death, the regime unveiled a giant fiberglass statue of Qassem Soleimani, the shadowy Iranian spymaster bombed in Baghdad under Trump’s direction.

But just hours after it was erected in the southwestern Iranian city of Shahrekord, mysterious assailants torched the prized effigy to the ground.

“These acts are important,” one MEK member says with a smile. “People are no longer afraid.”

This article first appeared in the Summer 2022 print edition of The Forward Observer, a special publication from Coffee or Die Magazine, as "Unfathomable Abuse."

Read Next: Russian Soldiers May Be Stealing Boats To Flee Battle as US Sends More Weapons

Hollie McKay is a foreign correspondent, war crimes investigator, and best-selling author. She was an investigative and international affairs/war journalist for Fox News Digital for over 14 years where she focused on warfare, terrorism, and crimes against humanity; in 2021 she founded international geopolitical risk and social responsibility firm McKay Global. Her columns have been featured in publications including the Wall Street Journal and The Spectator Magazine. Her latest book, Only Cry for the Living: Memos From Inside the ISIS Battlefield, is now available.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.