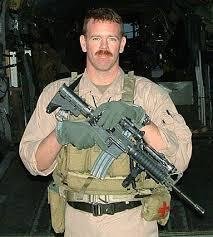

Photo by Tech. Sgt. Edward Gyokeres/ 621st Contingency Response Wing Public Affairs.

Dan “Yardbird” McCants and John “Irish” Quinlan were pilots in the U.S. Army’s elite 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment — known as the Night Stalkers — one of the units made famous in the movie “Black Hawk Down” and in the book “Not a Good Day to Die.” They were also my comrades and friends. They died in Zabul Province, Afghanistan, in February 2007, when their MH-47 helicopter crashed due to a mechanical malfunction.

Despite the fact that the Global War on Terror had been going on since 2001 and I had deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan multiple times, Dan and John were the first two U.S. soldiers who lost their lives downrange to whom I felt a personal connection.

At the time of this incident, which also killed or injured several of the flight crew and their Ranger passengers, I had moved on from the 160th and was serving in the Joint Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg. I was stateside at my desk in the JSOC compound when the news started coming in; first it was just a general notification that there was an incident with casualties and later, after the next of kin were notified, the names. Seeing the names of people I knew on a list like that was like a punch in the gut. I could only imagine what it must have been like for the families.

I met Dan at the 160th’s “Green Platoon,” the training and indoctrination program for those who made it through the initial assessment regimen on their way to becoming a Night Stalker. I don’t remember much about Officer Green Platoon — it’s kind of a blur. But I remember driving in on the first day and seeing a group of people in the “worm pit” covered with mud and on their backs doing flutter kicks while they were getting sprayed down by a cadre member holding a fire hose.

While that wasn’t exactly what I expected from the 160th’s Officer Green Platoon, that was what I was mentally prepared for. Fortunately for us, what I saw that morning was the Enlisted Green Platoon. While the officer version involved a figurative “drinking from the fire hose” in terms of the amount of information thrown our way, there were no literal fire hoses, and I was grateful for that.

Our Green Platoon class had maybe seven or eight people in it, all males, and I think everyone except for me was a pilot. The class was roughly split in half between officers and warrant officers. Despite the difference in jobs, I immediately felt a sense of togetherness and acceptance, which was a common thread throughout my time as a Night Stalker.

One of my few other memories from that time is that Dan always wanted to fight me during combatives training — not because he would win most of the time (although he did), but because I was so much bigger than him. He wanted to test himself against the toughest challenge in whatever it was he was doing. As a former Special Forces soldier who switched over to be a pilot in the most elite helicopter unit in the world, I suspect that was a big part of who he was. This constant competition and strive to be the best was a trait inherent in everyone in the 160th.

The one picture I have from my time in Green Platoon is all of us standing in front of Dan’s Jeep Wrangler, which was precariously parked on the side of an above-ground bunker in the “back 40” of Fort Campbell, in the training area where they used to store nuclear weapons.

John Quinlan I did not know well — we would say hi on the compound and that was about it. I remember him being big, friendly, and ready to talk to anyone. He was normally clean-shaven, but would occasionally sport a magnificent “deployment ’stache” when we were downrange. As they were pilots and I was on staff, I didn’t interact much with either John or Dan on a day-to-day basis. However, that changed during our deployments to Afghanistan. Dan and John were both video game enthusiasts, specifically when it came to “Call of Duty.” For the game, Dan chose the username “Yardbird” and John’s was “Irish,” which is why I referred to them as such at the beginning of this article.

I had picked up the book “Not A Good Day To Die” and realized that no fewer than four of the people mentioned in the book were in my unit.

Like most soldiers in the 160th, Dan and John were very competitive, and they wanted everyone else to compete with them. Dan was one of the pilots who pressured me into playing “Call of Duty” for the first time, and he was also one of the most vocal in his celebrations after winning. He was very good at the game and also very competitive about … everything. But he was especially competitive about “Call of Duty.” He was not alone in this regard; the game had a bit of a cult following in our unit.

The preferred method of playing “Call of Duty,” I found out, was support guys versus pilots. As the battalion intelligence officer (S2) and therefore a support guy, that automatically put me on the team opposite from Dan and John. Predictably, because they were experienced players and we support guys were not, the pilots dominated — at first. Eventually, the support guys started taking over the game. Dan’s skill level and smack talking made it even more fun to taunt him when we started winning.

Dan was one of the first people we targeted with our “Call of Duty” propaganda reporting. We did this by staging screenshots of game footage featuring his player name and sending it out as if it were an actual intel report. His reaction to that was exactly what we were looking for.

Although I had less interaction with John, it was still memorable. The first meaningful conversation I had with him was in the Dragon Dining Facility on Bagram Airbase, Afghanistan. I had picked up the book “Not A Good Day To Die” and realized that no fewer than four of the people mentioned in the book were in my unit, and at least two (possibly three) were in Afghanistan with me at the time. I thought John was one of them, but he explained that he wasn’t the person in the book that I thought was him. John had a reserved, patient manner that contrasted Dan’s high-energy approach to life — and that was probably one of the reasons they made a good flying team.

While I did not know Dan or John well, I am proud to call them brothers. They heeded the real call of duty to serve their country in combat, and they made the ultimate sacrifice for it. It may seem silly that, 12 years after their deaths, I’m writing about two men whose main interaction with me consisted of playing video games. But I think that’s a testament to the lasting impact they had on those around them and to the bonds made among soldiers who serve together in combat.

I do not play “Call of Duty” anymore, but I played frequently for a few years after I returned home from Afghanistan. After John and Dan died, I changed my call sign from “Major Pain” to “Irish&Yardbird,” and at the end of each game, I typed out “RIP John ‘Irish’ Quinlan and Dan ‘Yardbird’ McCants” in the game-wide chat in remembrance of them. It was a small thing I could do to help keep their memories alive.

At the end of the day, that’s all any of us can do — no matter how well we knew a fellow brother or sister in arms, remember them and help keep their memories alive. On this and every Memorial Day, let us #SayTheirNames.

RIP John “Irish” Quinlan and Dan “Yardbird” McCants, 2/160 SOAR, Afghanistan 2007. Irish&Yardbird. Night Stalkers Don’t Quit.

The Night Stalker Creed

Service in the 160th is a calling only a few will answer for the mission is constantly demanding and hard. And when the impossible has been accomplished the only reward is another mission that no one else will try.

As a member of the Night Stalkers I am a tested volunteer seeking only to safeguard the honor and prestige of my country, by serving the elite Special Operations Soldiers of the United States. I pledge to maintain my body, mind and equipment in a constant state of readiness for I am a member of the fastest deployable Task Force in the world – ready to move at a moment’s notice anytime, anywhere, arriving time on target plus or minus 30 seconds.

I guard my unit’s mission with secrecy, for my only true ally is the night and the element of surprise. My manner is that of the Special Operations Quiet Professional, secrecy is a way of life. In battle, I eagerly meet the enemy for I volunteered to be up front where the fighting is hard. I fear no foe’s ability, nor underestimate his will to fight.

The mission and my precious cargo are my concern. I will never surrender. I will never leave a fallen comrade to fall into the hands of the enemy and under no circumstances will I ever embarrass my country.

Gallantly will I show the world and the elite forces I support that a Night Stalker is a specially selected and well trained Soldier.

I serve with the memory and pride of those who have gone before me for they loved to fight, fought to win and would rather die than quit.

Night Stalkers Don’t Quit!

“The Lord knows the way I take, and when He has tested me, I shall come forth as gold.” Job 23:10

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Faint is a military intelligence officer with the United States Army and holds a master’s degree in International Relations from Yale University. He taught International Relations at West Point for three years, and also served in the 5th Special Forces Group, the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, and the Joint Special Operations Command, to include seven combat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. You can reach him at [email protected], and read more of his work on West Point’s Modern War Journal or on The Havok Journal. This article reflects his personal opinion based on his education and experience, and is not an official position of the U.S. Army or the U.S. Government.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.