How Merrill’s Marauders Waged an Unconventional War in the Burma Jungles of World War II

American soldiers, members of Gen. Frank Merrills Marauders, with trained Chinese soldiers on a jungle trail in Burma in the early 1940s. Photo by Keystone/Getty Images.

Hundreds of dead Japanese soldiers and pack animals lay piled at the edges of Nhpum Ga village’s thickly jungled perimeter in northern Burma, 1944. Cut down by sick, hungry, and exhausted Americans, the corpses — now bursting in the night from the humid jungle heat — created a blanket of stench swarming with thousands of bluebottle flies.

Anyone within a mile of Maggot Hill could smell the dead before they stumbled over them. Bullets rained from the defensive positions of Lt. Col. George McGee’s 2nd Battalion. They could only hold out for a little while longer as the Japanese threw their bodies against American machine-gun nests in suicidal banzai attacks. McGee yelled into the radio for reinforcements, desperate to keep his dwindling battalion alive.

In 1942 — two years before surrounding McGee’s position — Japanese forces had captured all of Burma in a crushing defeat of British Maj. Gen. Orde Wingate’s 77th Brigade, a long-range penetration unit nicknamed the “Chindits” after the Chinthe statues that guarded the Burmese pagodas. By chasing the British out of Burma, Japan cut off supply lines between British India and China — a crucial ally in the Pacific theater. American Maj. Gen. Joseph Stilwell led 117 of his own staff out of Burma alongside Wingate in a march of shame.

American commander Brig. Gen. Frank D. Merrill speaks about Merrill’s Marauders in Burma at a press conference, Aug. 24, 1944. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Stilwell wanted to retake Burma and said of his first retreat, “I claim we got a hell of a beating. We got run out of Burma and it is humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back and retake it.”

Without an overland route through Burma, supply flights to China would have to risk Allied pilots attempting routes over the Himalayan Mountains, home to nine of the 10 highest peaks on earth.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved long-range penetration teams at the Quebec Conference in August 1943, and by Oct. 30, three battalions with almost 3,000 volunteers “for a dangerous and hazardous mission” arrived in Bombay, India. The volunteer unit spent Christmas training in India, then moved out in January 1944 to support the Chinese in the Hukawng Valley.

Mount Everest, the highest peak in the world, rises 29,032 feet above Kathmandu, Nepal, out of the Himalayan Mountain Range along China's southern border. Several weather risks, including severe winds, avalanche and temperature hazards, and the Khumbu Icefall are only a few of the obstacles climbers face. Since 2019, over 300 people have died attempting to summit the mountain. Photo by Ehab Al-Hakawati/Unsplash.

On the ground in India, Stilwell took command of the American volunteers, the Chinese 22nd Division, and the British IV Corps. He appointed Frank D. Merrill as the commander of the newly designated 5307th Composite Regiment (Provisional).

James Shepley, of Life magazine, dubbed the unit “Merrill’s Marauders,” according to Gavin Mortimer’s 2013 book, Merrill’s Marauders: The Untold Story of Unit Galahad and the Toughest Special Forces Mission of World War II. “The 5307th didn’t exactly trip off the tongue,” Mortimer writes. But Dave Richardson, a reporter from Yank magazine embedded with the Marauders, referred to them as the “Dead End Kids” in his dispatches. “It was a greater mix than I’d ever run into in an outfit,” Richardson said, referring to the social, ethnic, and educational diversity of the volunteers.

The battalions were numbered as 1st, 2nd, and 3rd, each led by a lieutenant colonel. The three officers — William Osborne, George McGee, and Charles “Old Ranger” Beach — were grizzled veterans of the Pacific theater and experts in jungle warfare.

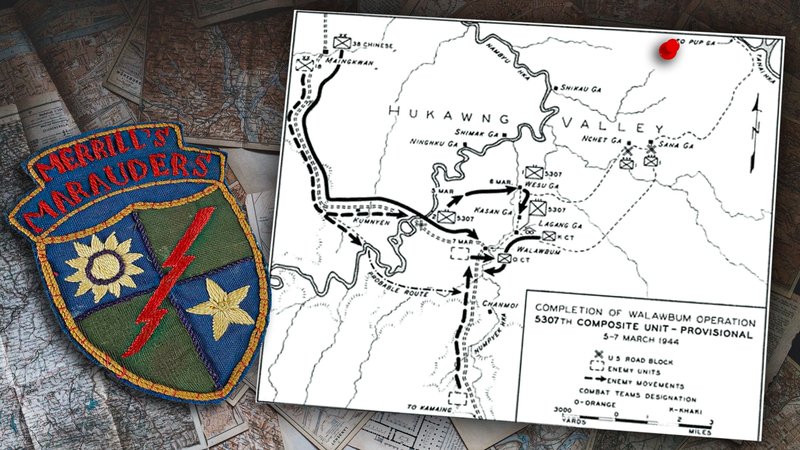

In the Hukawng Valley, deeply entrenched in tropical foliage and sucking mud, the Marauders followed the Kamaing Road to Walawbum, where they encountered heavy enemy resistance from Japanese banzai attacks and machine-gun fire, only adding to the heat and exhaustion already plaguing the unit. Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and Andrew Neel/Unsplash. Composite by Coffee or Die Magazine.

Stilwell’s plan to retake Burma consisted of a three-pronged attack. The Chinese forces would retake the northeast, while the British IV Corps assaulted the pockets of Japanese occupying the west. The Marauders would infiltrate central Burma as the main invasion force, keeping the focus of the Japanese 18th Division on the way to Myitkyina airstrip: a key point in the India-China air route. Initial estimates expected an 85% casualty rate among the Marauders.

To coincide with the Chinese 22nd Division’s assault on March 3, 1944, Merrill had only nine days to march 15 miles South via the Kamaing Road and attack Walawbum. The three battalions moved across the India-Burma border on foot, marching through jungle foliage so dense it blocked out the sun. On the path to Walawbum, Cpl. Werner Katz of 3rd Battalion, became the first Marauder to kill an enemy.

Katz recognized a Japanese patrol disguised as Chinese preparing to initiate an ambush. He opened fire and shot the enemy squad leader between the eyes. A reflexively fired bullet from the dead soldier ricocheted off of Katz’s wristwatch and hit him in the nose, requiring a few stitches.

"By the time the Marauders controlled Walawbum, they had killed more than 900 Japanese and suffered eight soldiers killed in action and 37 wounded."

Walawbum exploded in a hail of bombs and bullets when the Marauders arrived on March 3, but the Americans had an advantage during the chaotic battle. They had enlisted 14 Japanese American men known as Nisei for their grasp of the language. The Nisei translated enemy notes, messages, and maps, and later acted as interpreters for interrogations and prisoners of war. During the fight for Walawbum, Nisei Sgt. Roy Matsumoto listened and translated Japanese radio chatter, ultimately playing a key role in the American victory.

With no time to rest following the victory, the Marauders headed south to Shaduzup and Inkangahtawng to set up roadblocks along the Kamaing Road. The 1st Battalion headed to Shaduzup, while 2nd and 3rd Battalions left for Inkangahtawng.

In March, Stilwell received intelligence of a large Japanese force moving north to overtake Merrill’s Marauders and outflank their roadblocks. Merrill ordered 1st and 2nd Battalions to return to Nhpum Ga, while he and 3rd Battalion planned to move out to Hsamshingyang to establish an airstrip for later resupply. But Merrill suffered a heart attack, requiring evacuation, and command fell to his staff officer, Col. Charles Hunter.

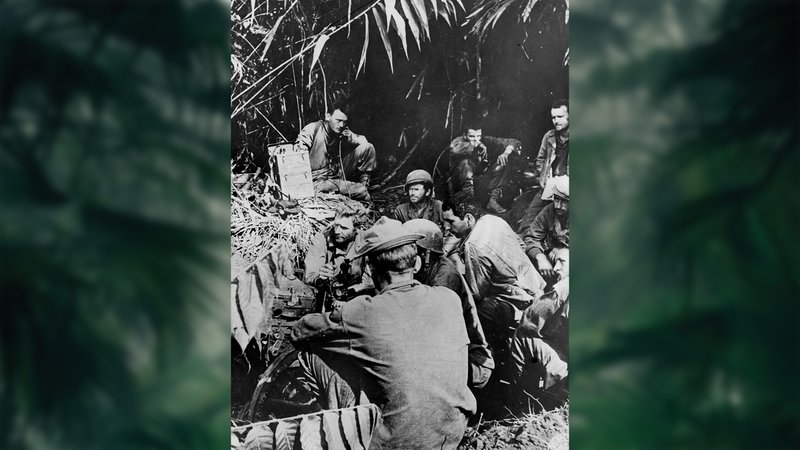

Members of Merrill’s Marauders wait to attack a Japanese machine-gun nest in the Burmese jungle, May 16, 1944. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

On March 30, 1944, 2nd Battalion arrived at Nhpum Ga, just before Japanese forces commenced their assault. The Marauders of 2nd Battalion held the line until 1st Battalion arrived to help. The reinforcements were a welcome sight to the beleaguered warriors crouched in artillery-chipped foxholes. On hearing 1st Battalion’s plea for help over the radio, 3rd Battalion called for a special airdrop: two pack howitzers.

The Marauders poured 134 75mm shells into the enemy positions until the Japanese called off their attack on Easter Sunday. The battle for Nhpum Ga resulted in 52 Marauders dead and 163 wounded. When the smoke cleared, the American position was surrounded by over 400 enemy dead. The stink from their bodies and the millions of maggots squirming across the battlefield prompted the survivors to rename the site Maggot Hill.

Following their victory at Nhpum Ga, the Marauders marched 62 miles at elevations as high as 6,600 feet through the Kumon Mountain Range to the Myitkyina airfield. Despite their exhaustion from typhoid, dysentery, leeches, malaria, snakebites, and malnourishment, the Marauders completed the journey, though it cost them more casualties than they incurred in battle.

A 75mm pack howitzer supports the weary Marauders at the siege of Myitkyina. As 1st and 2nd battalions were almost overwhelmed at Nphum Ga, 3rd battalion called for an airdrop of the artillery pieces and saved the day by pummeling the Japanese assaulting force with as many shells as they could load. The Marauders lugged the howitzer cannons the 62 miles to Myitkyina, where they were instrumental in taking the airfield. Public domain photo.

The Marauders surprised the Japanese forces and took Myitkyina airfield in less than two hours, sending the enemy retreating to the nearby Myitkyina village. Intelligence reports vastly underestimated the strength of the enemy’s forces, however, and the Marauders were forced to continue defending the airstrip in their ghastly state for the rest of the summer, enduring monsoon rains and relentless Japanese attacks.

The battle finally turned in the Allies’ favor when they were reinforced by a Chinese battalion on Aug. 3, 1944. When the Japanese finally capitulated, the Chinese held Myitkyina, and the Marauders — weary, sick, and starving — returned home to recover, leaving approximately 1,300 dead Japanese in their wake.

At the end of their mission in Burma, only about 200 Marauders of the initial 3,000 volunteers remained combat effective. Their legacy as long-range penetration teams lives on in the 75th Ranger Regiment.

This article first appeared in the Summer 2022 print edition of The Forward Observer, a special publication from Coffee or Die Magazine, as “The Dead End Kids.”

Read Next: From World War II to US Customs, Neal McCallum’s 46 Years Dedicated to Uncle Sam

Lauren Coontz is a former staff writer for Coffee or Die Magazine. Beaches are preferred, but Lauren calls the Rocky Mountains of Utah home. You can usually find her in an art museum, at an archaeology site, or checking out local nightlife like drag shows and cocktail bars (gin is key). A student of history, Lauren is an Army veteran who worked all over the world and loves to travel to see the old stuff the history books only give a sentence to. She likes medium roast coffee and sometimes, like a sinner, adds sweet cream to it.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.