The Origin and Evolution of ‘Johnny Got His Gun’ and Metallica’s ‘One’

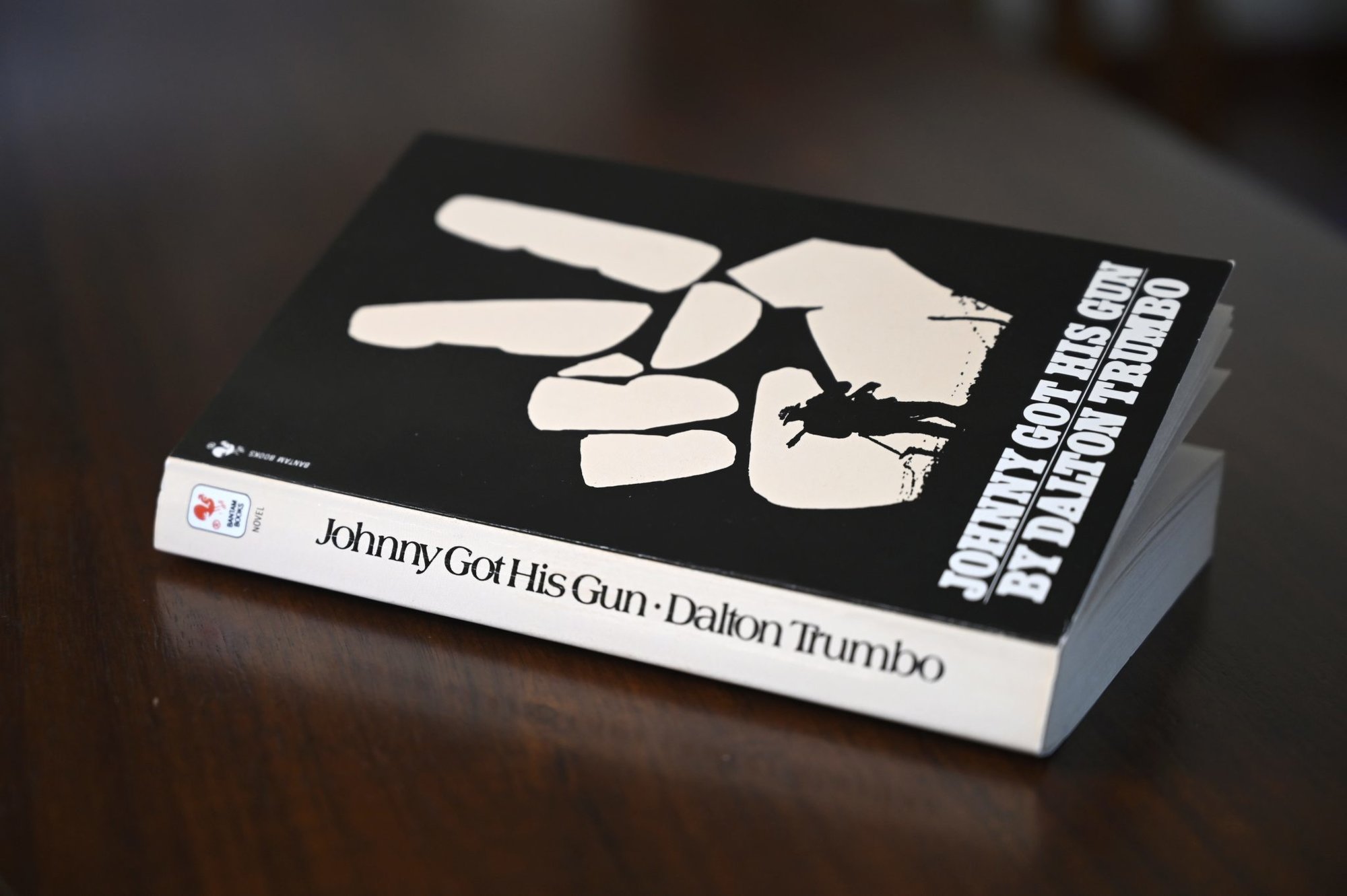

Paperback edition of Johnny Got His Gun from 1989. Photo by Ethan E. Rocke/Coffee or Die

When Metallica released …And Justice For All in 1988, the album was a game-changer for the band. Helped greatly by the wildly popular single One and its iconic music video, the album, which went multi-platinum, is the band’s artistic high-water mark.

Those of us Gen-Xers who subsisted as teenagers on a steady diet of metal and punk rock can attest to MTV’s role as an 800-pound gorilla of influence in American pop-culture in the ’80s and ’90s. Once the video dropped, One remained in constant rotation on MTV and became one of its most popular videos.

Justice is full of weighty lyrics about political and legal injustices such as censorship, environmental destruction, nuclear brinkmanship, and — of course — war. Lyrically speaking, One is undoubtedly an anti-war song. It tells the first-person story of a grievously wounded American soldier for whom life has become an endless nightmare:

Darkness imprisoning me/ All that I see/ Absolute horror/ I cannot live/ I cannot die/ Trapped in myself/ Body my holding cell/ Landmine has taken my sight/ Taken my speech/ Taken my hearing/ Taken my arms/ Taken my legs/ Taken my soul/ Left me with life in hell.

The song’s narrative is mostly derived from Dalton Trumbo’s 1939 novel Johnny Got His Gun. Trumbo’s acclaimed anti-war novel, which won an early National Book Award, is the first-person narrative of protagonist Joe Bonham, who wakes in a hospital bed to slowly discover that an enemy artillery shell has taken his arms and legs and left a mangled hole where his eyes, nose, teeth, and tongue used to be. Unable to hear or speak, Bonham’s entire being is reduced to a lonely consciousness trapped in a wrecked torso, and Trumbo effectively centers the reader in the prison of this nightmarish existence.

Metallica’s James Hetfield conceived the idea for One based on the notion of “just being a brain and nothing else,” according to loudersound.com. Hearing this, manager Cliff Burnstein recommended that Hetfield read Johnny.

With the exception of a landmine taking the place of an enemy artillery strike, Hetfield’s lyrics mirror the details from Trumbo’s book. The band famously purchased the rights to Trumbo’s 1971 film adaptation of Johnny and juxtaposed the film footage with black-and-white video of the band performing the epic tune in all their heart-pumping, rock-god glory.

What is perhaps most fascinating about the aesthetic marriage of Trumbo’s works and the song that made Metallica a household name is the extent to which Trumbo’s original intent is diluted by it. Johnny is arguably one of the only true antiwar novels/films ever written, and it succeeds as such because Trumbo’s singular focus was to subvert the romantic ideals with which war is so often presented.

Metallica, on the other hand, were focused on producing thrash metal anthems that perfectly appealed to the primitive drives of angsty, impressionable teens.

Lyrics be damned, heavy metal has always been a popular genre among America’s warrior class, and face-melting antiwar anthems are often reappropriated in contexts antithetical to their original purported intent. Heavy metal music, including Metallica’s, has been used in psychological operations in the War on Terror, and protest-metal titans like Rage Against the Machine and System of a Down are popular among American grunts.

How many grunts have headbanged downrange to lyrics such as, Everybody’s going to the party/ have a real good time/ Dancing in the desert/ blowing up the sunshine/ […] Why don’t presidents fight the war?/ Why do they always send the poor?

B.Y.O.B. shreds, bro.

In his bestselling memoir, Jarhead, Anthony Swofford makes a sobering argument that most antiwar books and films are anything but:

“There is talk that many Vietnam films are antiwar, that the message is war is inhumane and look what happens when you train young American men to fight and kill, they turn their fighting and killing everywhere, they ignore their targets and desecrate the entire country, shooting fully automatic, forgetting they were trained to aim. But actually, Vietnam war films are all pro-war, no matter what the supposed message, what Kubrick or Coppola or Stone intended. Mr. and Mrs. Johnson in Omaha or San Francisco or Manhattan will watch the films and weep and decide once and for all that war is inhumane and terrible, and they will tell their friends at church and their family this, but Corporal Johnson at Camp Pendleton and Sergeant Johnson at Travis Air Force Base and Seaman Johnson at Coronado Naval Station and Spec 4 Johnson at Fort Bragg and Lance Corporal Swofford at Twentynine Palms Marine Corps Base watch the same films and are excited by them, because the magic brutality of the films celebrates the terrible and despicable beauty of their fighting skills. Fight, rape, war, pillage, burn. Filmic images of death and carnage are pornography for the military man. […] It doesn’t matter how many Mr. and Mrs. Johnsons are antiwar—the actual killers who know how to use the weapons are not.”

While I generally agree with Swofford, I think there are occasionally exceptions to this rule, and Trumbo’s Johnny, with its unflinching focus on the agonizing hindsight of a soldier ruined by a needless war, stands as the quintessential antiwar novel.

When the novel’s protagonist realizes he has no chance of taking his own life and the doctors and nurses won’t kill him, he decides he wants to be placed in a glass box and toured around the country in order to show others the true horrors of war — a request that is denied because it’s “against regulations.”

A highly successful Jewish-American screenwriter and novelist who scripted many award-winning films, Trumbo was a proud leftist who refused to name names and testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947. He was one of the many artists blacklisted in Hollywood during the red scare that swept the country after World War II. Bryan Cranston portrayed Trumbo in the 2015 biopic Trumbo.

Trumbo described World War I as “the last of the romantic wars,” and his task throughout Johnny is to strip away any semblance of romance with war from the reader’s mind. It’s important to note, however, that Trumbo, who served in World War II, was not outright antiwar. In his introduction to a 1959 reprint of Johnny, Trumbo described how he opposed efforts to use his novel for the antiwar cause in World War II:

“After Pearl Harbor, its subject matter seemed inappropriate to the times. […] There are times when it may be needful for certain private rights to give way to the requirements of a larger public good. I know that’s a dangerous thought, and I shouldn’t wish to carry it too far, but World War II was not a romantic war.

“As the conflict deepened, and Johnny went out of print altogether, its unavailability became a civil liberties issue with the extreme American right. Peace organizations and Mothers’ groups from all over the country showered me with fiercely sympathetic letters denouncing Jews, Communists, New Dealers and international bankers, who had suppressed my novel to intimidate millions of true Americans who demanded an immediate negotiated peace.

“My correspondents, a number of whom used elegant stationary and sported tidewater addresses, maintained a network of communications that extended to the detention camps of pro-Nazi internees. […] They proposed a national rally for peace-now, with me as cheerleader; they promised (and delivered) a letter campaign to pressure the publisher for a fresh edition.

“Nothing could have convinced me so quickly that Johnny was exactly the sort of book that shouldn’t be reprinted until the war was at an end. The publishers agreed.”

So in an ironic twist, the author of America’s quintessential antiwar novel actively worked against its use as such during a war whose cause he seemed to believe was just and necessary. By 1970, however, Trumbo had long since resumed his antiwar posture, decrying the war in Vietnam with the signature rhetoric that made him a literary powerhouse:

“If the [40,000] dead mean nothing to us (except on Memorial Day weekend when the national freeway is clotted with surfers, swimmers, skiers, picnickers, campers, hunters, fishers, footballers, beer-busters), what of our 300,000 wounded? Does anyone know where they are? How they feel? How many arms, legs, ears, noses, mouths, faces, penises they’ve lost? How many are deaf or dumb or blind or all three? How many are single or double or triple or quadruple amputees? How many will remain immobile for the rest of their days? How many hang on as decerebrated vegetables quietly breathing their lives away in small, dark, secret rooms?”

No doubt Trumbo’s strong feelings about the war in Vietnam influenced his decision to write and direct the film adaptation of Johnny in 1971 when the American public was largely divided over the conflict. While the film received mixed reviews, it won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival and resonated with the antiwar crowd.

Trumbo, who died in 1976, never got to see how his work inspired Metallica’s One and found, at the height of the MTV era, a new audience and mode of expression that was far less equipped to effectively communicate the antiwar message that Trumbo conveyed so poignantly in 1939 when he wrote what stands as the only example I know of that can truly be called an antiwar novel.

Ethan E. Rocke is a contributor and former senior editor for Coffee or Die Magazine, a New York Times bestselling author, and award-winning photographer and filmmaker. He is a veteran of the US Army and Marine Corps. His work has been published in Maxim Magazine, American Legion Magazine, and many others. He is co-author of The Last Punisher: A SEAL Team THREE Sniper’s True Account of the Battle of Ramadi.

BRCC and Bad Moon Print Press team up for an exclusive, limited-edition T-shirt design!

BRCC partners with Team Room Design for an exclusive T-shirt release!

Thirty Seconds Out has partnered with BRCC for an exclusive shirt design invoking the God of Winter.

Lucas O'Hara of Grizzly Forge has teamed up with BRCC for a badass, exclusive Shirt Club T-shirt design featuring his most popular knife and tiomahawk.

Coffee or Die sits down with one of the graphic designers behind Black Rifle Coffee's signature look and vibe.

Biden will award the Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War Army helicopter pilot who risked his life to save a reconnaissance team from almost certain death.

Ever wonder how much Jack Mandaville would f*ck sh*t up if he went back in time? The American Revolution didn't even see him coming.

A nearly 200-year-old West Point time capsule that at first appeared to yield little more than dust contains hidden treasure, the US Military Academy said.